en

names in breadcrumbs

Die Saagvisse (Pristidae) is 'n kraakbeenvis-familie wat hoort tot die orde Pristiformes. Daar is twee genera met ses spesies wat hoort tot dié familie en drie van die spesies kom aan die Suid-Afrikaanse kus voor.

Die uitstaande kenmerk van die familie is die plat snawel met tande aan weerskante wat soos 'n saag lyk. Die kop en voorste gedeelte van die lyf is plat terwyl die agterste gedeelte meer soos die lyf van 'n haai lyk. Die familie het twee dorsale vinne, 'n asimmetriese stertvin (die boonste lob is langer) en die pektorale vinne is langs die kop geheg en lyk amper soos twee vlerke. Daar is vyf pare kieue splete teenwoordig aan die onderkant van die kop. Die familie word tot 7 m lank - die saag ingesluit en is ovovivipaar. Hulle kom voor in vlak water by sanderige bodems, soms in riviermondings. Die familie is eetbaar. Die saag word gebruik om kos uit te krap en ook om prooi mee dood te maak.

Die volgende genera en gepaardgaande spesies kom aan die Suid-Afrikaanse kus voor:

Die Saagvisse (Pristidae) is 'n kraakbeenvis-familie wat hoort tot die orde Pristiformes. Daar is twee genera met ses spesies wat hoort tot dié familie en drie van die spesies kom aan die Suid-Afrikaanse kus voor.

Los pristiformes (del lat. pristis, "pez sierra") son un orde de elasmobranquios del superorde Batoidea, conocíos vulgarmente como pez sierra. Inclúin una sola familia, Pristidae, con dos xéneros y siete especies.[2]

Los pexes sierra tán más rellacionaos coles rayes que colos tiburones. La so apariencia ye la d'un pexe con un focico llargu y llenu de dientes. Tienen un cadarma cartilaxinosu.

Nun tienen de ser confundíos colos tiburones sierra (orde Pristiophoriformes), que tienen una apariencia similar.

Les dimensiones de los pexes sierra van de 1,5 m a 6 m. La carauterística más sobresaliente del pexe sierra ye, poques gracies, la so focico con forma de sierra. Ésti atópase cubiertu con poros sensibles al movimientu y a la eletricidá, que-yos dexa detectar el movimientu ya inclusive los llatíos cardiacos de preses soterraes nel sedimentu marino. El so focico actúa entós como un detector mientres el pexe sierra nada sobre'l fondu marín, en busca d'alimentu. El so focico tamién sirve como ferramienta escavador pa desenterrar crustáceos.

Cuando una presa nada cerca, el pexe sierra ataca dende embaxo y utiliza furiosamente la so sierra. Esto xeneralmente manca a la presa lo suficiente por que'l pexe taramiar ensin muncha dificultá. Los pexes sierra tamién utilicen la so focico como arma de defensa contra otru depredadores como tiburones, delfines y buzus intrusos. Los dientes que sobresalen del focico nun son verdaderos dientes, sinón escames dentales modificaes.

El cuerpu y la cabeza de los pexes sierra son apandaos yá que pasen la mayoría del tiempu recostados nel suelu marín. Al igual que les rayes, la so boca ta alcontrada nel so parte inferior. Na so boca esisten pequeños dientes pa comer pequeños crustáceos y otros pexes, anque dacuando taramiar enteros.

Los pexes sierra alienden por dos espiráculos alcontraos detrás de los sos güeyos que conducen l'agua a les branquies. El so piel ta cubierta por pequeños dentículos que-y dan una testura rasposa. El so color ye xeneralmente gris o café, anque la especie Pristis pectinata ye color verde oliva.

Los güeyos de los pexes sierra nun tán bien desenvueltos pola so hábitat lodoso. El so focico ye la so principal ferramienta sensorial. Los sos intestíns tienen forma de sacacorchos.

Los pexes sierra alcontrar n'árees tropicales y subtropicales alredor d'África, Australia y el Caribe. Los pexes sierra viven n'agües pocu fondes y lodosas, n'agües salaes y duces. La mayoría prefier boques de ríu y sistemes d'agua duce. Tolos pexes sierra tien l'habilidá de camudar d'agües salaes a agües duces, y xeneralmente facer, nadando dientro de ríos, según en badees y estuarios.

Son nocherniegos; usualmente duermen mientres el día y cacen a la nueche. A pesar de les apariencies, son pexes que nun ataquen a les persones nun siendo que sían provocaos o sosprendíos.

Poco se conoz sobre la la reproducción del pexe sierra. Cada individuu vive ente 25 y 30 años, maureciendo a los 10.

Maurecen amodo; envalórase que nun se reproducen hasta qu'algamen ente 3,5 y 4 metros de llargu y tienen ente 10 y 12 años d'edá, y reprodúcense a niveles inmensamente menores que la mayoría de los pexes. Esto fai qu'a estos animales cuéste-yos demasiáu recuperase, cuantimás tres una sobrepesca.

Los pristiformes (del lat. pristis, "pez sierra") son un orde de elasmobranquios del superorde Batoidea, conocíos vulgarmente como pez sierra. Inclúin una sola familia, Pristidae, con dos xéneros y siete especies.

Los pexes sierra tán más rellacionaos coles rayes que colos tiburones. La so apariencia ye la d'un pexe con un focico llargu y llenu de dientes. Tienen un cadarma cartilaxinosu.

Nun tienen de ser confundíos colos tiburones sierra (orde Pristiophoriformes), que tienen una apariencia similar.

Ar pesked-heskenn eo ar pesked mor a ya d'ober ar c'herentiad Pristidae. Kondriktied (pesked migornek) int, evel ar rinkined hag ar raeed.

Ar pesked-heskenn eo ar pesked mor a ya d'ober ar c'herentiad Pristidae. Kondriktied (pesked migornek) int, evel ar rinkined hag ar raeed.

Els peixos serra (Pristidae, del Grec πριστήρ pristēr que significa "serra") són una família d'animals marins emparentats amb els taurons i les rajades. El tret característic més punyent és la presència d'un morro llarg i dentat. En l'ordre Pristiformes només hi ha la família Pristidae.

No s'han de confondre amb els taurons serra (ordre Pristiophoriformes), que tenen una aparença física similar.

Totes les espècies de peix serra es troben en perill, o en perill greu i el comerç internacional d'aquestes està prohibit.[1] Capturar-los és il·legal als Estats Units i a Austràlia.

La primera característica que s'aprecia del peix serra és el seu morro en forma de serra, anomenat rostrum. El rostrum està cobert per porus electrosensitius que el permeten detectar moviment i fins i tot els batecs cardíacs d'una possible presa amagada sota la sorra del fons marí. El rostrum serveix també com a eina per a excavar a la recerca de crustacis enterrats. Quan un peix serra detecta una presa adient s'hi abraona i l'ataca furiosament amb la seva serra. Generalment això fereix suficientment la presa perquè el peix serra la pugui devorar sense massa resistència. Els peixos serra també utilitzen el rostrum per a defensar-se dels depredadors (com els taurons) i intrusos diversos. Les "dents" que sobresurten del rostrum no són dents de debò sinó escates modificades.

Tant el cos com el cap dels peixos serra són plans, adaptats per a passar la major part del temps reposant sobre el fons marí. Com les rajades, la boca i les narius dels peixos serra se situen a la part inferior del cos. La boca està aprovisionada de petites dents en forma de cúpula per a menjar petits peixos i crustacis, tot i que a vegades se'ls poden empassin sencers. Els peixos serra respiren per dos espiracles que se situen just entre els ulls, a través dels quals inspiren aigua cap a les brànquies. La pell és coberta per diminuts denticles dèrmics que els atorga una textura rugosa. Els peixos serra generalment són d'un color gris o marró, mentre que el Pristis pectinata presenta un color verd oliva.

Els peixos serra es troben en àrees tropicals i subtropicals al voltant d'Àfrica i Austràlia i al Carib, no és rar que remuntin els rius terra endins.

Viuen en aigües fangoses i poc fondes i es poden trobar tant en aigua dolça com salada. La majoria prefereixen viure a les boques dels rius i els sistemes d'aigua dolça. Tots els peixos serra posseeixen l'habilitat de travessar el pas d'aigua dolça a salada, i sovint ho fan.

Els peixos serra són nocturns, dormint usualment durant el dia, caçant de nit. Tot i l'aparença monstruosa d'aquests peixos, són tranquils i no ataquen als humans si no són provocats o sorpresos.

Es sap poca cosa sobre els hàbits reproductius dels peixos serra. Cada individu viu entre 25 i 30 anys, i madura als 10 anys.

S'ha estimat que s'aparellen cada dos anys. Maduren lentament - no es reprodueixen fins que no assumeixen entre 3,5 i 4 metres de longitud i 10 o 12 anys - i tenen unes tasses de reproducció molt més petites que la majoria dels peixos. Aquest fet els dificulta la recuperació de la sobreexplotació pesquera.[2]

Els peixos serra (Pristidae, del Grec πριστήρ pristēr que significa "serra") són una família d'animals marins emparentats amb els taurons i les rajades. El tret característic més punyent és la presència d'un morro llarg i dentat. En l'ordre Pristiformes només hi ha la família Pristidae.

No s'han de confondre amb els taurons serra (ordre Pristiophoriformes), que tenen una aparença física similar.

Totes les espècies de peix serra es troben en perill, o en perill greu i el comerç internacional d'aquestes està prohibit. Capturar-los és il·legal als Estats Units i a Austràlia.

Savfisk er en familie af rokker som er karakteriseret af en forlænget snude besat med talrige tænder. Flere arter af savfisk kan blive op til 7,5 meter. Familien er kun studeret meget lidt, hvorfor kendskabet til adfærd og reproduktion er meget begrænset. Alle arter af savfisk er truet af udryddelse. Savfisk bør ikke forveksles med savhajer (Pristiophoridae) som har en lignende kropsbygning.

Savfiskens kropsbygning er meget hajagtig med to store rygfinner og en kraftig asymmetrisk halefinne. Kroppen og hovedet er fladtrykt. Øjnene er dårligt udviklede, måske fordi den fortrinsvis lever i mudrede områder. Bag øjnende har savfisken to åndehuller, hvor vandet til gællerne trækkes igennem. Undersiden af fisken er flad og her findes næseborene, munden og gællespalterne. Der er 5 gællespalter i hver side. Munden er foret med små kuppelformede tænder som er velegnede til at spise mindre fisk og krebsdyr. Den forlængede snude benævnes ofte rostrum eller sværd. Den er fladtrykt og indeholder sanseceller, som savfisken kan benytte til at spore byttedyr, som gemmer sig i bundlaget. Sværdet kan bruges til at grave i bunden efter krebsdyr eller andet bytte. Med kraftige sideværts sving kan sværdet også bruges til såre eller dræbe byttedyr som svømmer forbi og endelig kan savfisken bruge sværdet til at forsvare sig mod fjender. Tænderne på sværdet er ikke tænder i egentlig forstand men omdannede hudtænder. De vokser hele tiden og erstattes med nye tænder, hvis de falder af. Ligesom andre bruskfisk, mangler savfisk svømmeblære og anvender i stedet deres store, oliefyldte lever til at styre opdriften. Savfisk er normalt lys grå eller brune med undtagelse af Pristis pectinata som er olivengrøn.

Savfisk er et bundlevende natdyr og tilbringer det meste af dagen liggende på havbunden.

På trods af deres frygtindgydende udseende, angriber de ikke mennesker medmindre de bliver provokeret eller overrasket.

Der kendes kun lidt til reproduktionen hos savfisk. Det formodes at savfisk parrer en gang hvert andet år, med en gennemsnitlig kuld på omkring otte. De kønsmodnes meget langsomt, og det skønnes, at de større arter ikke bliver kønsmodne, før de er 3,5 til 4 meter lange og 10 til 12 år gamle. Deres reproduktionsrate er lavere end de fleste andre fisk, og det betyder at bestandene er særlig langsomme til at komme sig efter overfiskning. Savfisk er ovovivipar dvs. æggene befrugtes og udvikles inde i moderen. Æggenes klækkes inden ungerne fødes. Indtil ungerne fødes er deres semi-hærdede sværd dækket med en membran. Dette forhindrer ungen i at skade sin mor under fødslen. Membranen nedbrydes sidenhen og falder af.

Savfisk findes i Atlanterhavet, det Indiske Ocean og dele af Stillehavet i tropiske og subtropiske kystregioner. De findes ofte i mudrede bugter og floddeltaer. Alle arter kan tåle ferskvand og kan migrere op i floder.

Slægten Anoxypristis

Slægten Pristis

Alle arter af savfisk betragtes kritisk truet. De fanges som bifangst i fiskenet eller jages for deres sværd (som er værdsat af samlere), deres finner (som regnes for en delikatesse), eller olie fra deres lever (til brug i folkemedicin).

Mens finner fra mange hajarter udnyttes i handelen, er visse arter blevet identificeret til at levere de mest velsmagende og saftige finner. De haj-lignende rokker (såsom savfisk og guitarfisk) anses for at leverer den højeste kvalitet af finner. Finnerne fra de stærkt truede savfisk er meget efterspurgte på de asiatiske markeder og er nogle af de mest værdifulde "hajfinner". Savfisk er nu beskyttet under det højeste beskyttelsesniveau i konventionen om international handel med udryddelsestruede dyrearter (CITES), tillæg I, men i betragtning af det store omfang af hajfinne handlen, og at afskårne hajfinner er vanskelige at identificere, er det usandsynligt, at CITES beskyttelsen vil forhindre at finner fra savfisk inddrages i handelen.

Det er ulovligt at fange savfisk i USA og i Australien. Det er også forbudt at sælge sværdet af småtandet savfisk i USA under Endangered Species Act (ESA). Alligevel er de fleste sværd på det amerikanske marked fra småtandet savfisk, fordi salg af sværdet fra andre savfisk stadig er lovlig og lægfolk har svært ved at skelne mellem arterne.

Savfisk er en familie af rokker som er karakteriseret af en forlænget snude besat med talrige tænder. Flere arter af savfisk kan blive op til 7,5 meter. Familien er kun studeret meget lidt, hvorfor kendskabet til adfærd og reproduktion er meget begrænset. Alle arter af savfisk er truet af udryddelse. Savfisk bør ikke forveksles med savhajer (Pristiophoridae) som har en lignende kropsbygning.

Sägerochen (Pristidae (Gr.: „pristis“ = Säge)), oft auch Sägefische genannt und von den Sägehaien zu unterscheiden, sind Rochen, die einen eher gestreckten, haiähnlichen Körper haben. Ihr auffallendstes Merkmal ist die "Säge", ein knorpeliger, seitlich mit Zähnen besetzter Auswuchs des Kopfes, der mehr als 25 % der Gesamtlänge der Fische ausmachen kann. Die Säge dient dem Beutefang. Dazu schwimmen die Tiere in Fischschwärme und schlagen dann mit der Säge hin und her, um anschließend die verletzten Opfer zu fressen. Weiterhin wird sie benutzt, um in schlammigem Boden nach Weich- und Krebstieren zu wühlen. Die Säge dient auch als Sinnesorgan für elektromagnetische Signale, um Beutetiere aufzuspüren.

Sägerochen sind große Rochen und erreichen ausgewachsen eine Länge von 2,4 bis 5, nach einigen Berichten sogar 6 bis 8 Metern. Nur Pristis clavata bleibt mit 1,40 Meter eher klein. Der Körper ist leicht abgeflacht und haiartig. Der Schwanzstiel ist sehr kräftig, seitlich abgeflacht und verfügt über seitliche Kiele. Der Übergang vom Körper zum Schwanzstiel verläuft allmählich. Der Körper ist mit kleinen Placoidschuppen bedeckt. Größere Stacheln sind weder auf der Körperoberseite noch auf dem Schwanzstiel vorhanden. Der Kopf ist abgeflacht und trägt die namensgebende "Säge", ein stark verlängertes, flaches Rostrum, das zu beiden Seiten mit je einer Reihe von sägezahnartigen gleichförmigen Zähnen besetzt ist. Die Zähne sitzen in tiefen Sockeln, wachsen ständig weiter und werden bei Verlust durch nachwachsende ersetzt. Die Säge ist vor allem ein Sinnesorgan, um Beutetiere aufzuspüren, und dient daneben dazu, durch Stochern im Boden Nahrung aufzuscheuchen oder Schwarmfische durch wildes Hin- und Herschlagen bewegungsunfähig zu machen oder zu töten. Die Augen auf der Kopfoberseite befinden sich weit vor den Spritzlöchern. Auf der Kopfunterseite befinden sich auf jeder Seite fünf Kiemenspalten etwa auf Höhe der Mitte der Brustflossenbasis. Kiemenreusenstrahlen fehlen. Das Maul an der Kopfunterseite steht quer, ist gerade und ohne Gruben, Falten oder ähnliche Merkmale. Die Nasenöffnungen liegen vor dem Maul, stehen weit auseinander und sind deutlich vom Maul getrennt. Die vorderen Nasenklappen sind kurz, nicht miteinander verbunden und erreichen auch nicht das Maul. Die Kieferzähne sind sehr klein, von runder oder ovaler Form und ohne irgendwelche Spitzen. Sie sitzen in 60 oder mehr Reihen in jedem Kiefer, sind uniform und nicht plattenartig.

Die Brustflossen sind im Vergleich zu denen anderer Rochen relativ klein und nicht mit dem Rumpf zu einer Körperscheibe verwachsen. Sie setzen an den hinteren Kopfseiten hinter dem Maul an und enden deutlich vor dem Beginn der Bauchflossenbasis. Die Bauchflossen sind dreieckig und nicht in zwei Loben geteilt. Auf der Oberseite befinden sich zwei große und gleich große Rückenflossen, die sichelförmig oder dreieckig sein können. Sie stehen weit auseinander: die erste vor oder über der Bauchflossenbasis, die zweite auf dem Schwanzstiel. Die Schwanzflosse ist groß und ähnelt der der Haie. Sie ist asymmetrisch (heterocerk), die Wirbelsäule verläuft in der Schwanzflosse nach oben und stützt den oberen Lobus. Der untere Lobus kann mehr oder weniger gut entwickelt sein oder auch ganz fehlen. Sägerochen sind oberseits von gelblicher, brauner, grünlicher oder graubrauner Farbe, der Bauch ist weißlich. Weder auf dem Körper noch auf den Flossen finden sich Zeichnungen oder Markierungen irgendwelcher Art.

Sägerochen können nur mit Sägehaien (Pristiophoridae) verwechselt werden, die ebenfalls ein sägeartiges Rostrum haben. Diese leben jedoch eher in tieferen Meeresregionen und gemäßigten Breiten. Ihre Kiemenöffnungen befinden sich an den Kopfseiten und vor den Brustflossenbasen. Ihr Körper ist weniger abgeflacht, die Sägezähne am Rostrum sind kleiner und auch dessen Unterseite ist mit einer Reihe kleiner Zähne besetzt. In der Mitte des Sägehairostrums findet sich an den Seiten ein Paar langer Barteln.

Sägerochen leben in tropischen Bereichen des Atlantiks und des Indopazifiks in Küstennähe. Fünf Arten leben an der nördlichen Küste Australiens. Manche Arten gehen auch in die Brackwasserzonen und schwimmen mehrere hundert Kilometer in die Unterläufe großer Flüsse Südostasiens, Neuguineas, Australiens und des Amazonas. Pristis microdon ist in Australien als Süßwassersägerochen bekannt. Große Populationen von Pristis perotteti waren aus dem Nicaraguasee bekannt, wo sie in den 70er Jahren durch kommerziellen Fang wahrscheinlich ausgerottet wurden. Erst 2006 wurden Sägerochen und der Bullenhai (Carcharhinus leucas) in Nicaragua unter Schutz gestellt.

Der Gewöhnliche Sägefisch (Pristis pristis) kommt auch in subtropischen Gewässern vor, z. B. im westlichen Mittelmeer oder im kühleren Ostpazifik vom Golf von Kalifornien bis nach Ecuador.

Sägerochen sind langsam schwimmende Fische, die ihre aus Wirbellosen und kleinen Fischen bestehende Nahrung vor allem in Bodennähe aufnehmen. Schwarmfische werden durch schnelle seitliche Schläge mit der Säge getötet oder verletzt und dann gefressen.

Sägerochen sind eilebendgebärend (ovovivipar). Sie können mehr als 20 Junge bekommen. Die Säge ist bei der Geburt noch weich und wird erst hart, wenn der bei der Geburt sehr große Dottersack aufgebraucht ist.

Schon 1758 wurde der erste Sägefisch durch den Begründer der binären Nomenklatur Carl von Linné in seiner Systema Naturae als Squalus pristis (heute Pristis pristis) beschrieben. Die Familie der Sägerochen (Pristidae) wurde 1838 durch den Biologen Charles Lucien Bonaparte aufgestellt. Meist werden die Pristidae heute einer eigenständigen Ordnung (Pristiformes) innerhalb der Rochen zugeordnet. Phylogenetisch stehen die Sägerochen jedoch tief innerhalb einer Klade von verschiedenen Geigenrochengattungen. Die Geigenrochen werden dadurch zu einem paraphyletischen Taxon.[1] Einer neuen, Säge- und Geigenrochen umfassende Ordnung, wurde der Name Rhinopristiformes gegeben.[2]

Es gibt zwei Gattungen, davon ist eine monotypisch, und fünf Arten:[3]

Gattung Wissenschaftlicher Name Trivialname IUCN status Verbreitung Anoxypristis Pristis clavata

Pristis clavata Pristis pectinata

Pristis pectinata Pristis pristis

Pristis pristis Pristis zijsron

Pristis zijsronFossil treten Sägerochen gesichert ab dem Eozän auf, darunter bereits die beiden rezenten Gattungen Anoxypristis und Pristis. Nur fossil bekannt ist die Gattung Propristis, die in eozänen Ablagerungen West-Afrikas und Nordamerikas gefunden wurde. Ein sehr früher Sägerochen ist möglicherweise Peyeria aus dem Cenoman des östlichen Nordafrika, aber seine Zuordnung zu den Pristiden ist umstritten.

Rein fossile Vertreter und äußerlich den Sägerochen stark ähnelnd sind die sogenannten Pseudosägerochen (Sclerorhynchidae). Diese Gruppe gilt als die Schwestergruppe einer Klade aus Sägerochen und anderen Rochenfamilien, das heißt, die Sägerochen sind wahrscheinlich mit anderen Rochenfamilien enger verwandt als mit den Pseudosägerochen und der „Sägerochen-Habitus“ hat sich in beiden Familien unabhängig voneinander entwickelt (konvergente Evolution).[14][15] Die Pseudosägerochen lebten von der Oberkreide bis ins Paläozän und wurden vor allem in den USA gefunden. Exemplare von Libanopristis, Micropristis und Sclerorhynchus stammen aus dem Libanon.[16]

Es wird vermutet, dass die Sägerochen erst deshalb im Paläogen eine höhere Diversität entwickeln konnten, weil die heute von ihnen besetzte ökologische Nische bis dahin durch die Pseudosägerochen besetzt war.

Alle Sägerochenarten sind weltweit vom Aussterben bedroht und stehen auf der Roten Liste (IUCN). Sie werden vor allem als Beifang gefischt, verheddern sich schnell mit ihrer Säge in Netzen und haben nicht die Möglichkeit, sich alleine zu befreien. Außerdem werden Sägen noch immer als Trophäen gesammelt und für die traditionelle chinesische Medizin verwendet, weil ihnen heilende Wirkung zugesprochen wird. Um ein erhöhtes Bewusstsein für die weltweite Gefährdung der Sägerochenarten zu schaffen, wurde 2017 von der American Associations of Zoos and Aquariums und der Sawfish Conservation Society der 17. Oktober zum Tag des Sägefischs („Sawfish Day“) ernannt.[17]

Sägerochen (Pristidae (Gr.: „pristis“ = Säge)), oft auch Sägefische genannt und von den Sägehaien zu unterscheiden, sind Rochen, die einen eher gestreckten, haiähnlichen Körper haben. Ihr auffallendstes Merkmal ist die "Säge", ein knorpeliger, seitlich mit Zähnen besetzter Auswuchs des Kopfes, der mehr als 25 % der Gesamtlänge der Fische ausmachen kann. Die Säge dient dem Beutefang. Dazu schwimmen die Tiere in Fischschwärme und schlagen dann mit der Säge hin und her, um anschließend die verletzten Opfer zu fressen. Weiterhin wird sie benutzt, um in schlammigem Boden nach Weich- und Krebstieren zu wühlen. Die Säge dient auch als Sinnesorgan für elektromagnetische Signale, um Beutetiere aufzuspüren.

Ang mga tag-an[2][3][4] o barasan (Ingles: sawfish [literal na "isdang-lagare"] ay isang pamilya ng mga hayop-dagat na kaugnay ng mga pating at mga batoidea (mga manta). Kabilan sa pinakanatatanging kaanyuan nila ang mahaba at mangiping mga nguso. Kasapi sila sa mga pamilyang Pristidae sa loob ng ordeng Pristiformes, na nagmula ang pangalan sa Griyegong pristēs na nangangahulugang "isang lagari". Hindi sila dapat ikalito sa mga bukawin (ordeng Pristiophoriformes, tinatawag ding katambak o sapingan, mga "lagaring pating"), na may kahawig na anyong pangpangangatawan. Dahil nga sa pagkakahawig na ito, may kamaliang natatawag din ang mga tag-an bilang mga lagaring-pating[5] din.

Itinuturing ang lahat ng mga uri ng mga tag-an na lubhang nanganganib at ipinagbabawal ang pandaigdigang pangangalakal ng mga ito.[6]

Ang mga tag-an o barasan (Ingles: sawfish [literal na "isdang-lagare"] ay isang pamilya ng mga hayop-dagat na kaugnay ng mga pating at mga batoidea (mga manta). Kabilan sa pinakanatatanging kaanyuan nila ang mahaba at mangiping mga nguso. Kasapi sila sa mga pamilyang Pristidae sa loob ng ordeng Pristiformes, na nagmula ang pangalan sa Griyegong pristēs na nangangahulugang "isang lagari". Hindi sila dapat ikalito sa mga bukawin (ordeng Pristiophoriformes, tinatawag ding katambak o sapingan, mga "lagaring pating"), na may kahawig na anyong pangpangangatawan. Dahil nga sa pagkakahawig na ito, may kamaliang natatawag din ang mga tag-an bilang mga lagaring-pating din.

Itinuturing ang lahat ng mga uri ng mga tag-an na lubhang nanganganib at ipinagbabawal ang pandaigdigang pangangalakal ng mga ito.

Το Πριονόψαρο είναι ψάρι των αλμυρών υδάτων, το οποίο ανήκει στο γένος Pristis, της οικογένειας των πριστίδων και τάξης των σελαχομόρφων, αριθμεί, περίπου, πέντε είδη. Τα σημαντικότερα από αυτά είναι τα είδη:Pristis pristis, Pristis pectinata, Pristis microdon. Όλα τα είδη κινδυνεύουν με εξαφάνιση λόγω της παράνομης αλιείας τους και της καταστροφής του φυσικού τους περιβάλλοντος. Γενικά, είναι ένα "δειλό" ψάρι, όμως, γίνεται επικίνδυνο όταν του επιτεθούν.

Το πριονόψαρο, αν και μοιάζει με καρχαρία, ανήκει στα σελάχια. Έχει καφέ-λαδί-γκρίζο χρώμα στην ράχη και λευκό στην κοιλιά. Το χαρακτηριστικό γνώρισμα του ψαριού αυτού είναι το μακρύ ρύγχος του, το οποίο μοιάζει με πριόνι. Το μήκος του φτάνει τα 2 με 9 μέτρα και καλύπτεται από μικρά λέπια.

Το πριονόψαρο τρέφεται, κυρίως, με μικρά ψάρια και καρκινοειδή. Προμηθεύεται την τροφή του ψάχνοντας στην άμμο ή στην λάσπη του βυθού, είτε χτυπώντας ψάρια που είναι συγκεντρωμένα σε κοπάδια με την βοήθεια του ρύγχους του.

Το πριονόψαρο ζει σε τροπικές θάλασσες.

Pristis pristis: Το βάρος του φτάνει τα 700 κιλά΄, κατά μέσο όρο, και το μήκος του τα 4 με 9 μέτρα. Ζει στα παράκτια θερμά νερά του Ατλαντικού και μερικές φορές φτάνει εώς την Μεσόγειο θάλασσα. Επίσης, συναντάται στον Ειρηνικό Ωκεανό, στην περιοχή της Αυστραλίας.

Pristis microdon: Το μήκος του φτάνει τα 6 μέτρα. Συναντάται στις τροπικές ζώνες και των τριών ωκεανών.

Pristis pectinatus: Το μήκος του φτάνει τα 4 μέτρα περίπου. Συναντάται στις τροπικές ζώνες και των τριών ωκεανών.

http://www.emprosnet.gr/emprosnet-archive/8b390aef-fd00-4c7a-9344-8eb8cf2b19ec

http://www.ygeiaonline.gr/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=45037:prionocaro

Βιβλιογραφία: Εγκυκλοπαίδεια "Νεα Δομή", Εκδόσεις «ΔΟΜΗ», Αθήνα, 1996, τόμος 29

Το Πριονόψαρο είναι ψάρι των αλμυρών υδάτων, το οποίο ανήκει στο γένος Pristis, της οικογένειας των πριστίδων και τάξης των σελαχομόρφων, αριθμεί, περίπου, πέντε είδη. Τα σημαντικότερα από αυτά είναι τα είδη:Pristis pristis, Pristis pectinata, Pristis microdon. Όλα τα είδη κινδυνεύουν με εξαφάνιση λόγω της παράνομης αλιείας τους και της καταστροφής του φυσικού τους περιβάλλοντος. Γενικά, είναι ένα "δειλό" ψάρι, όμως, γίνεται επικίνδυνο όταν του επιτεθούν.

வேளா மீன் (Sawfish) அல்லது தச்சன் சுறா (Carpenter shark) என்பது ஒரு திருக்கை குடும்ப மீனாகும். இவற்றிற்கு நீண்ட தட்டையான கொம்பு அல்லது முக்கு உள்ளது. கொம்பின் இரு ஒரங்களிலில் ரம்பப் பற்கள் போன்ற கூரான பற்கள் உள்ளன. இந்த மீன்களில் பல இனங்கள் உள்ளன. இந்த மீன்கள் 7 m (23 ft) நீளம்வரை வளரக்கூடியன.[2][3][4] இக்குடும்ப மீன்கள்பற்றி பெரியதாக அறியப்படாமல் உள்ளது காரணம் இவைபற்றி சிறிய அளவே ஆய்வு செய்யப்பட்டுள்ளது. இதன் பெயர் பண்டைய கிரேக்க மொழியில்: πρίστης prístēs "saw, sawyer".[5] இருந்து பெறப்பட்டது.

இந்த வாள் சுறாக்களின் தனித்துவமான அமைப்பு தன் நீண்ட வாள் கொம்பு அமைப்புதான். இவை இந்தக் கொம்பு, கடலடி சகதியைக் கிளறி அங்கு மறைந்திருக்கும் கடல் உயிரினங்களை வேட்டையாட உதவுகிறது. மேலும் மீன் கூட்டங்களில் புகுந்து தன் வாள் கொம்பால் மீன்களைத் தாக்கிக் காயமாக்கி தத்தளிக்கும் மீனை பிடித்து உண்ணும்.

வேளா மீன் (Sawfish) அல்லது தச்சன் சுறா (Carpenter shark) என்பது ஒரு திருக்கை குடும்ப மீனாகும். இவற்றிற்கு நீண்ட தட்டையான கொம்பு அல்லது முக்கு உள்ளது. கொம்பின் இரு ஒரங்களிலில் ரம்பப் பற்கள் போன்ற கூரான பற்கள் உள்ளன. இந்த மீன்களில் பல இனங்கள் உள்ளன. இந்த மீன்கள் 7 m (23 ft) நீளம்வரை வளரக்கூடியன. இக்குடும்ப மீன்கள்பற்றி பெரியதாக அறியப்படாமல் உள்ளது காரணம் இவைபற்றி சிறிய அளவே ஆய்வு செய்யப்பட்டுள்ளது. இதன் பெயர் பண்டைய கிரேக்க மொழியில்: πρίστης prístēs "saw, sawyer". இருந்து பெறப்பட்டது.

ಗರಗಸ ಮೀನು ಪ್ರಪಂಚದ ಉಷ್ಣವಲಯ ಸಾಗರಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಕಾಣಸಿಗುವ ಒಂದು ಬಗೆಯ ಮೃದ್ವಸ್ಥಿ ಮೀನು (ಸಾ ಫಿಶ್). ಶಾರ್ಕ್, ರೇ, ಸ್ಕೇಟ್ ಮೀನುಗಳ ವರ್ಗದಲ್ಲಿ ಸ್ಕ್ವಾಲಿಫಾರ್ಮಿಸ್ ಗಣದ ಪ್ರಿಸ್ಟಿಡೆ ಕುಟುಂಬದ ಮೀನು. ಇದರ ಶಾಸ್ತ್ರೀಯ ಹೆಸರು ಪ್ರಿಸ್ಟಿಸ್. ಅಕ್ಕ ಪಕ್ಕದಲ್ಲಿ ಚೂಪಾದ ಹಲ್ಲುಗಳಿರುವ ಮತ್ತು ಬಲು ಉದ್ದವಾಗಿರುವ ಗರಗಸದಂಥ ಮೂತಿಯಿರುವುದರಿಂದ ಇದಕ್ಕೆ ಈ ಹೆಸರು.ಇದು ಸುಮಾರು ೭ ಮೀಟರ್ ಉದ್ದವಿರುತ್ತದೆ.[೧][೨]

ಇದರಲ್ಲಿ ಆರು ಪ್ರಬೇಧಗಳಿವೆ. ಇವುಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಅಮೆರಿಕದ ಆಗ್ನೇಯ ಹಾಗೂ ಗಲ್ಫ್ ತೀರ ಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಕಾಣಬರುವ ಪೆಕ್ಟಿನೇಟಸ್ ಪ್ರಭೇದ, ಮೆಡಿಟರೇನಿಯನ್ ಮತ್ತು ಅಟ್ಲಾಂಟಿಕ್ ಸಾಗರಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಕಾಣಬರುವ ಆಂಟಿಕೋರಮ್ ಪ್ರಭೇದ ಮತ್ತು ಭಾರತದ ತೀರ ಪ್ರದೇಶಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಸಿಕ್ಕುವ ಕಸ್ಪಿಡೇಟಸ್ ಮತ್ತು ಮೈಕ್ರೋಡಾನ್ ಪ್ರಭೇದಗಳು ಪ್ರಮುಖವಾದವು.

ಗರಗಸ ಮೀನುಗಳು ತೀರಕ್ಕೆ ಸಮೀಪದಲ್ಲಿ ಮತ್ತು ಅಳಿವೆಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಜೀವಿಸುವುವು. ಅನೇಕ ಸಂದರ್ಭದಲ್ಲಿ ನದಿಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಒಳನಾಡಿಗೂ ಹಲವಾರು ಮೈಲಿಗಳಷ್ಟು ದೂರ ಬರುವುದೂ ಉಂಟು.

ಇದು ಸು. 6.1 ಮೀ ಗಳವರೆಗೆ ಬೆಳೆಯುತ್ತದೆ. ದೇಹರಚನೆಯಲ್ಲಿ ಶಾರ್ಕ್ ಮೀನನ್ನು ಹೋಲುತ್ತದಾದರೂ ಇದು ರೇ ಮೀನುಗಳ ಹತ್ತಿರದ ಸಂಬಂಧಿ ಅಂದರೆ ಕಿವಿರು ದ್ವಾರಗಳು ದೇಹದ ತಳ ಭಾಗದಲ್ಲಿರುತ್ತವೆ. (ಶಾರ್ಕ್ ಮೀನುಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಕಿವಿರು ದ್ವಾರಗಳು ದೇಹದ ಪಾರ್ಶ್ವದಲ್ಲಿರುತ್ತವೆ). ಅಗಲವಾದ ಎದೆಯ ಈಜುರೆಕ್ಕೆಗಳು, ಎರಡು ಬೆನ್ನಿನ ಈಜುರೆಕ್ಕೆಗಳು, ಬಾಲದ ಈಜುರೆಕ್ಕೆ, ಗರಗಸದಂತಹ ಮೂತಿ, ತಲೆಯ ಕೆಳಭಾಗದಲ್ಲಿನ ಅರ್ಧಚಂದ್ರಾಕೃತಿಯ ಬಾಯಿ, ಬಾಲದ ಆಚೀಚೆ ದೋಣಿಯ ಆಕಾರದ ಚರ್ಮದ ಮಡಿಕೆ-ಇವು ಗರಗಸ ಮೀನಿನ ಬಾಹ್ಯ ಲಕ್ಷಣಗಳು. ಮೂತಿ ಚಪ್ಪಟೆಯಾಗಿ ಬಲು ಉದ್ದವಾಗಿರುತ್ತದೆ; ಕೆಲವು ಮೀನುಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಸು. 1.8ಮೀ ಉದ್ದವಿರುತ್ತದೆ. ಅದರ ಒಂದೊಂದು ಅಲುಗಿನಲ್ಲಿ ಚೂಪಾದ ಸುಮಾರು 22-32 ಹಲ್ಲುಗಳಿರುತ್ತವೆ. ಸಾಗರತಳವನ್ನು ಹೆಕ್ಕಿ ಅದರೊಳಗಿರುವ ಹಲವಾರು ಬಗೆಯ ಪ್ರಾಣಿಗಳನ್ನು ತಿನ್ನಲು ಈ ಗರಗಸವನ್ನು ಬಳಸುತ್ತದೆ. ಅಲ್ಲದೆ ಚಲಿಸುವಾಗ ಸಣ್ಣ ಮೀನುಗಳ ಗುಂಪಿನಲ್ಲಿ ಮಧ್ಯೆ ನುಗ್ಗಿ ಗರಗಸವನ್ನು ಅತ್ತಿತ್ತ ಬಲವಾಗಿ ಆಡಿಸಿ ಕೆಲವು ಮೀನುಗಳು ಇದರ ಹೊಡೆತಕ್ಕೆ ಸಿಕ್ಕಿ ಸಾಯುವಂತೆ ಮಾಡಿ ತಿನ್ನುವುದೂ ಉಂಟು. ಗರಗಸ ಮೀನು ಜರಾಯುಜ ಪ್ರಾಣಿ. ಹುಟ್ಟುವ ಮುನ್ನವೇ ಮರಿಗಳಿಗೆ ಗರಗಸವಿರುವುದಾದರೂ ಅದು ಬಲು ಮೃದುವಾಗಿಯೂ ಒಂದು ಬಗೆಯ ಹೊದಿಕೆಯಿಂದ ಆವೃತವಾಗಿರುವುದರಿಂದ ತಾಯಿಯ ಹೊಟ್ಟೆಲ್ಲಿರುವಾಗ ಅಲ್ಲಿನ ಅಂಗಾಂಶಗಳಿಗೆ ಹಾನಿಯಾಗುವ ಸಂಭವವಿರುವುದಿಲ್ಲ.

ಮಲೇಶಿಯಾ, ಇಂಡೋನೇಶಿಯಾ ಮತ್ತು ಚೀನಾಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಗರಗಸ ಮೀನನ್ನು ತಿನ್ನುತ್ತಾರೆ. ಇದರ ಮಾಂಸ ಶಾರ್ಕ್ ಮೀನಿನ ಮಾಂಸದಷ್ಟೇ ರುಚಿ ಎಂದು ಹೇಳಲಾಗಿದೆ. ಅಲ್ಲದೆ ಈ ಮೀನಿನ ಚರ್ಮದಿಂದ ಕತ್ತಿಯ ಒರೆಯನ್ನು ಮಾಡುವುದಿದೆ. ಇದರ ಯಕೃತ್ತಿನಿಂದ ಎಣ್ಣೆಯನ್ನು ತೆಗೆಯುತ್ತಾರೆ.

ಗರಗಸ ಮೀನು ಪ್ರಪಂಚದ ಉಷ್ಣವಲಯ ಸಾಗರಗಳಲ್ಲಿ ಕಾಣಸಿಗುವ ಒಂದು ಬಗೆಯ ಮೃದ್ವಸ್ಥಿ ಮೀನು (ಸಾ ಫಿಶ್). ಶಾರ್ಕ್, ರೇ, ಸ್ಕೇಟ್ ಮೀನುಗಳ ವರ್ಗದಲ್ಲಿ ಸ್ಕ್ವಾಲಿಫಾರ್ಮಿಸ್ ಗಣದ ಪ್ರಿಸ್ಟಿಡೆ ಕುಟುಂಬದ ಮೀನು. ಇದರ ಶಾಸ್ತ್ರೀಯ ಹೆಸರು ಪ್ರಿಸ್ಟಿಸ್. ಅಕ್ಕ ಪಕ್ಕದಲ್ಲಿ ಚೂಪಾದ ಹಲ್ಲುಗಳಿರುವ ಮತ್ತು ಬಲು ಉದ್ದವಾಗಿರುವ ಗರಗಸದಂಥ ಮೂತಿಯಿರುವುದರಿಂದ ಇದಕ್ಕೆ ಈ ಹೆಸರು.ಇದು ಸುಮಾರು ೭ ಮೀಟರ್ ಉದ್ದವಿರುತ್ತದೆ.

Sawfish, also known as carpenter sharks, are a family of rays characterized by a long, narrow, flattened rostrum, or nose extension, lined with sharp transverse teeth, arranged in a way that resembles a saw. They are among the largest fish with some species reaching lengths of about 7–7.6 m (23–25 ft).[2] They are found worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions in coastal marine and brackish estuarine waters, as well as freshwater rivers and lakes. All species are endangered.[3]

They should not be confused with sawsharks (order Pristiophoriformes) or the extinct sclerorhynchoids (order Rajiformes) which have a similar appearance, or swordfish (family Xiphiidae) which have a similar name but a very different appearance.[1][4]

Sawfishes are relatively slow breeders and the females give birth to live young.[2] They feed on fish and invertebrates that are detected and captured with the use of their saw.[5] They are generally harmless to humans, but can inflict serious injuries with the saw when captured and defending themselves.[6]

Sawfish have been known and hunted for thousands of years,[7] and play an important mythological and spiritual role in many societies around the world.[8]

Once common, sawfish have experienced a drastic decline in recent decades, and the only remaining strongholds are in Northern Australia and Florida, United States.[4][9] The five species are rated as Endangered or Critically Endangered by the IUCN.[10] They are hunted for their fins (shark fin soup), use of parts as traditional medicine, their teeth and saw. They also face habitat loss.[4] Sawfish have been listed by CITES since 2007, restricting international trade in them and their parts.[11][12] They are protected in Australia, the United States and several other countries, meaning that sawfish caught by accident have to be released and violations can be punished with hefty fines.[13][14]

The scientific names of the sawfish family Pristidae and its type genus Pristis are derived from the Ancient Greek: πρίστης, romanized: prístēs, lit. 'saw, sawyer'.[15][16]

Despite their appearance, sawfish are rays (superorder Batoidea). The sawfish family has traditionally been considered the sole living member of the order Pristiformes, but recent authorities have generally subsumed it into Rhinopristiformes, an order that now includes the sawfish family, as well as families containing guitarfish, wedgefish, banjo rays and the like.[17][18] Sawfish quite resemble guitarfish, except that the latter group lacks a saw, and their common ancestor likely was similar to guitarfish.[5]

The species level taxonomy in the sawfish family has historically caused considerable confusion and was often described as chaotic.[7] Only in 2013 was it firmly established that there are five living species in two genera.[4][19]

Anoxypristis contains a single living species that historically was included in Pristis, but the two genera are morphologically and genetically highly distinct.[1][20] Today Pristis contains four living, valid species divided into two species groups. Three species are in the smalltooth group, and there is only a single in the largetooth group.[4] Three poorly defined species were formerly recognized in the largetooth group, but in 2013 it was shown that P. pristis, P. microdon and P. perotteti do not differ in morphology or genetics.[19] As a consequence, recent authorities treat P. microdon and P. perotteti as junior synonyms of P. pristis.[3][21][22][23][24][25]

In addition to the living sawfish, there are several extinct species that only are known from fossil remains. The oldest known is the monotypic genus Peyeria whose remains date back 100 million years, from the Cenomanian age (Late Cretaceous),[1] though it may represent a rhinid rather than a sawfish.[27] Indisputable sawfish genera emerged in the Cenozoic age about 60 million years ago, relatively soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene mass extinction. Among these are Propristis, a monotypic genus only known from fossil remains, as well as several extinct Pristis species and several extinct Anoxypristis species (both of these genera are also represented by living species).[1][28] Historically, palaeontologists have not separated Anoxypristis from Pristis.[1] In contrast, several additional extinct genera are occasionally listed, including Dalpiazia, Onchopristis, Oxypristis,[29] and Mesopristis,[28] but recent authorities generally include the first two in the family Sclerorhynchidae and the last two are synonyms of Anoxypristis.[1][30] Fossils of sawfish have been found around the world in all continents.[29]

The extinct family Sclerorhynchidae resemble sawfish. They are known only from Cretaceous fossils,[1][31] and usually reached lengths only of approximately 1 m (3.3 ft).[5][27] Some have suggested that sawfish and sclerorhynchids form a clade, the Pristiorajea,[31] while others believe the groups are not particularly close, making the proposed clade polyphyletic.[27]

Sawfish are dull brownish, greyish, greenish or yellowish above,[2] but the shade varies and dark individuals can be almost black.[32] The underside is pale,[32] and typically whitish.[2]

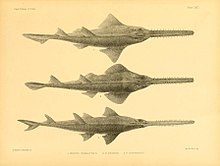

The most distinctive feature of sawfish is their saw-like rostrum with a row of whitish teeth (rostral teeth) on either side of it. The rostrum is an extension of the chondrocranium ("skull"),[27] made of cartilage and covered in skin.[33] The rostrum length is typically about one-quarter to one-third of the total length of the fish,[5] but it varies depending on species, and sometimes with age and sex.[1] The rostral teeth are not teeth in the traditional sense, but heavily modified dermal denticles.[34] The rostral teeth grow in size throughout the life of the sawfish and a tooth is not replaced if it is lost.[34][35] In Pristis sawfish the teeth are found along the entire length of the rostrum, but in adult Anoxypristis there are no teeth on the basal one-quarter of the rostrum (about one-sixth in juvenile Anoxypristis).[36][37] The number of teeth varies depending on the species and can range from 14 to 37 on each side of the rostrum.[2][38][note 1] It is common for a sawfish to have slightly different tooth counts on each side of its rostrum (difference typically does not surpass three).[39][40] In some species, females on average have fewer teeth than males.[1][39] Each tooth is peg-like in Pristis sawfish, and flattened and broadly triangular in Anoxypristis.[2] A combination of features, including fins and rostrum, are typically used to separate the species,[2][38] but it is possible to do it by the rostrum alone.[41]

Sawfish have a strong shark-like body, a flat underside and a flat head. Pristis sawfish have a rough sandpaper-like skin texture because of the covering of dermal denticles, but in Anoxypristis the skin is largely smooth.[2] The mouth and nostrils are placed on the underside of the head.[2] There are about 88–128 small, blunt-edged teeth in the upper jaw of the mouth and about 84–176 in the lower jaw (not to be confused with the teeth on the saw). These are arranged in 10–12 rows on each jaw,[42] and somewhat resemble a cobblestone road.[43] They have small eyes and behind each is a spiracle, which is used to draw water past the gills.[44] The gill slits, five on each side, are placed on the underside of the body near the base of the pectoral fins.[43] The position of the gill openings separates them from the superficially similar, but generally much smaller (up to c. 1.5 m or 5 ft long) sawsharks, where the slits are placed on the side of the neck.[1][45] Unlike sawfish, sawsharks also have a pair of long barbels on the rostrum ("saw").[1][45]

Sawfish have two relatively high and distinct dorsal fins, wing-like pectoral and pelvic fins, and a tail with a distinct upper lobe and a variably sized lower lobe (lower lobe relatively large in Anoxypristis; small to absent in Pristis sawfish).[2] The position of the first dorsal fin compared to the pelvic fins varies and is a useful feature for separating some of the species.[2] There are no anal fins.[42]

Like other elasmobranches, sawfish lack a swim bladder (instead controlling their buoyancy with a large oil-rich liver), have a skeleton consisting of cartilage,[46] and the males have claspers, a pair of elongated structures used for mating and positioned on the underside at the pelvic fins.[42] The claspers are small and indistinct in young males.[38]

Their small intestines contain an internal partition shaped like a corkscrew, called a spiral valve, which increases the surface area available for food absorption.

Sawfish are large to very large fish, but the maximum size of each species is generally uncertain. The smalltooth sawfish, largetooth sawfish and green sawfish are among the world's largest fish. They can certainly all reach about 6 m (20 ft) in total length and there are reports of individuals larger than 7 m (23 ft), but these are often labeled with some uncertainty.[2] Typically reported maximum total lengths of these three are from 7 to 7.6 m (23–25 ft).[2] Large individuals may weigh as much as 500–600 kg (1,102–1,323 lb),[47] or possibly even more.[48][49] Old unconfirmed and highly questionable reports of much larger individuals do exist, including one that reputedly had a length of 9.14 m (30 ft), another that had a weight of 2,400 kg (5,300 lb), and a third that was 9.45 m (31 ft) long and weighed 2,591 kg (5,712 lb).[48]

The two remaining species, the dwarf sawfish and narrow sawfish, are considerably smaller, but are still large fish with a maximum total length of at least 3.2 m (10.5 ft) and 3.5 m (11.5 ft) respectively.[2][50] In the past it was often reported that the dwarf sawfish only reaches about 1.4 m (4.6 ft), but this is now known to be incorrect.[51]

Sawfish are found worldwide in tropical and subtropical waters.[3]

Historically they ranged in the East Atlantic from Morocco to South Africa,[52] and in the West Atlantic from New York (United States)[32] to Uruguay, including the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.[3] There are old reports (last in the late 1950s or shortly after) from the Mediterranean and these have typically been regarded as vagrants,[3] but a review of records strongly suggests that this sea had a breeding population.[53] In the East Pacific they ranged from Mazatlán (Mexico) to northern Peru.[54] Although the Gulf of California occasionally has been included in their range, the only known Pacific Mexican records of sawfish are from south of its mouth.[54] They were widespread in the western and central Indo-Pacific, ranging from South Africa to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, east and north to Korea and southern Japan, through Southeast Asia to Papua New Guinea and Australia.[3] Today sawfish have disappeared from much of their historical range.[3]

Sawfish are primarily found in coastal marine and estuarine brackish waters, but they are euryhaline (can adapt to various salinities) and also found in freshwater.[2] The largetooth sawfish, alternatively called the freshwater sawfish, has the greatest affinity for freshwater.[55] For example, it has been reported as far as 1,340 km (830 mi) up the Amazon River and in Lake Nicaragua, and its young spend the first years of their life in freshwater.[21] In contrast, the smalltooth, green and dwarf sawfish typically avoid pure freshwater, but may occasionally move far up rivers, especially during periods when there is an increased salinity.[51][56][57] There are reports of narrow sawfish seen far upriver, but these need confirmation and may involve misidentifications of other species of sawfish.[58]

Sawfish are mostly found in relatively shallow waters, typically at depths less than 10 m (33 ft),[3] and occasionally less than 1 m (3.3 ft).[56] Young prefer very shallow places and are often found in water only 25 cm (10 in) deep.[4] Sawfish can occur offshore, but are rare deeper than 100 m (330 ft).[3] An unidentified sawfish (either a largetooth or smalltooth sawfish) was captured off Central America at a depth in excess of 175 m (575 ft).[59]

The dwarf and largetooth sawfish are strictly warm-water species that generally live in waters that are 25–32 °C (77–90 °F) and 24–32 °C (75–90 °F) respectively.[51][55] The green and smalltooth sawfish also occur in colder waters, in the latter down to 16–18 °C (61–64 °F), as illustrated by their (original) distributions that ranged further north and south of the strictly warm-water species.[55][60] Sawfish are bottom-dwellers, but in captivity it has been noted that at least the largetooth and green sawfish readily take food from the water surface.[55] Sawfish are mostly found in places with soft bottoms such as mud or sand, but may also occur over hard rocky bottoms or at coral reefs.[61] They are often found in areas with seagrass or mangrove.[3]

Sawsharks are typically found much deeper, often at depths in excess of 200 m (660 ft), and when shallower mostly in colder subtropical or temperate waters than sawfish.[1][45]

Relatively little is known about the reproductive habits of the sawfish, but all species are ovoviviparous with the adult females giving birth to live young once a year or every second year.[3] In general, males appear to reach sexual maturity at a slightly younger age and smaller size than females.[3] As far as known, sexual maturity is reached at an age of 7–12 years in Pristis and 2–3 years in Anoxypristis. In the smalltooth and green sawfish this equals a total length of 3.7–4.15 m (12.1–13.6 ft), in the largetooth sawfish at 2.8–3 m (9.2–9.8 ft), in the dwarf sawfish about 2.55–2.6 m (8.4–8.5 ft), and in the narrow sawfish at 2–2.25 m (6.6–7.4 ft).[3] This means that the generation length is about 4.6 years in the narrow sawfish and 14.6–17.2 years in the remaining species.[3]

Mating involves the male inserting a clasper, organs at the pelvic fins, into the female to fertilize the eggs.[33] As known from many elasmobranchs, the mating appears to be rough, with the sawfish often sustaining lacerations from its partner's saw.[62] However, through genetic testing it has been shown that at least the smalltooth sawfish also can reproduce by parthenogenesis where no male is involved and the offspring are clones of their mother.[63][64] In Florida, United States, it appears that about 3% of the smalltooth sawfish offspring are the result of parthenogenesis.[65] It is speculated that this may be in response to being unable to find a partner, allowing the females to reproduce anyway.[64][65]

The pregnancy lasts several months.[33] There are 1–23 young in each sawfish litter, which are 60–90 cm (2–3 ft) long at birth.[3][33] In the embryos the rostrum is flexible and it only hardens shortly before birth.[33] To protect the mother the saws of the young have a soft cover, which falls off shortly after birth.[66][67] The pupping grounds are in coastal and estuarine waters. In most species the young generally stay there for the first part of their lives, occasionally moving upriver when there is an increase in salinity.[51][56][57][68] The exception is the largetooth sawfish where the young move upriver into freshwater where they stay for 3–5 years, sometimes as much as 400 km (250 mi) from the sea.[59] In at least the smalltooth sawfish the young show a degree of site fidelity, generally staying in the same fairly small area in the first part of their lives.[69] In the green and dwarf sawfish there are indications that both sexes remain in the same overall region throughout their lives with little mixing between the subpopulations. In the largetooth sawfish the males appear to move more freely between the subpopulations, while mothers return to the region where they were born to give birth to their own young.[70][71]

The length of the full lifespan of sawfish is labeled with considerable uncertainty. A green sawfish caught as a juvenile lived for 35 years in captivity,[55] and a smalltooth sawfish lived for more than 42 years in captivity.[72] In the narrow sawfish it has been estimated that the lifespan is about 9 years, and in the Pristis sawfish it has been estimated that it varies from about 30 to more than 50 years depending on the exact species.[3]

The rostrum (saw), unique among jawed fish, plays a significant role in both locating and capturing prey.[73][74] The head and rostrum contain thousands of sensory organs, the ampullae of Lorenzini, that allow the sawfish to detect and monitor the movements of other organisms by measuring the electric fields they emit.[75] Electroreception is found in all cartilaginous fishes and some bony fishes. In sawfish the sensory organs are packed most densely on the upper- and underside of the rostrum, varying in position and numbers depending on the species.[75][73] Utilizing their saw as an extended sensing device, sawfish are able to examine their entire surroundings from a position close to the seafloor.[1] It appears that sawfish can detect potential prey by electroreception from a distance of about 40 cm (16 in).[5] Some waters where sawfish live are very murky, limiting the possibility of hunting by sight.[71]

Sawfish are predators that feed on fish, crustaceans and molluscs.[2] Old stories of sawfish attacking large prey such as whales and dolphins by cutting out pieces of flesh are now considered to be wholly unsubstantiated.[1][60] Humans are far too large to be considered potential prey.[76] In captivity they are typically fed ad libitum or in set amounts that (per week) equal 1–4% of the total weight of the sawfish, but there are indications that captives grow considerably faster than their wild counterparts.[55]

Exactly how they use their saw after the prey has been located has been debated, and some scholarship on the subject has been based on speculations rather than real observations.[5][74] In 2012 it was shown that there are three primary techniques, informally called "saw in water", "saw on substrate" and "pin".[74] If a prey item such as a fish is located in the open water, the sawfish uses the first method, making a rapid swipe at the prey with its saw to incapacitate it. It is then brought to the seabed and eaten.[5][55][74] The "saw on substrate" is similar, but used on prey at the seabed.[5][74] The saw is highly streamlined and when swiped it causes very little water movement.[77] The final method involves pinning the prey against the seabed with the underside of the saw, in a manner similar to that seen in guitarfish.[5][74] The "pin" is also used to manipulate the position of the prey, allowing fish to be swallowed head-first and thus without engaging any possible fin spines.[5][74] The spines of catfish, a common prey, have been found imbedded in the rostrum of sawfish.[33] Schools of mullets have been observed trying to escape sawfish.[78] Prey fish are typically swallowed whole and not cut into small pieces with the saw,[33] although on occasion one may be split in half during capture by the slashing motion.[5] Prey choice is therefore limited by the size of the mouth.[27] A 1.3 m (4.3 ft) sawfish had a 33 cm (13 in) catfish in its stomach.[71]

It had been suggested that sawfish use their saw to dig/rake in the bottom for prey,[79] but this was not observed during a 2012 study,[74] or supported by later hydrodynamic studies.[77] Large sawfish often have rostral teeth with tips that are notably worn.[35]

Old stories often describe sawfish as highly dangerous to humans, sinking ships and cutting people in half, but today these are considered myths and not factual.[1][60] Sawfish are actually docile and harmless to humans, except when captured, where they can inflict serious injuries when defending themselves by thrashing the saw from side-to-side.[6][16][55] The saw is also used in self-defense against predators such as sharks that may eat sawfish.[33] In captivity, they have been seen using their saws during fights over hierarchy or food.[71]

The largetooth sawfish was among the species formally described by Carl Linnaeus (as "Squalus pristis") in Systema Naturae in 1758,[21] but sawfish were already known thousands of years earlier.[7]

Sawfish were occasionally mentioned in antiquity, in works such as Pliny's Natural History (77–79 AD).[4] Pristis, the scientific name formalised for sawfish by Linnaeus in 1758, was also in use as a name even before his publication. For example, sawfish or "priste" were included in Libri de piscibus marinis in quibus verae piscium effigies expressae sunt by Guillaume Rondelet in 1554, and "pristi" were included in De piscibus libri V, et De cetis lib. vnus by Ulisse Aldrovandi in 1613. Outside Europe, sawfish are mentioned in old Persian texts, such as 13th century writings by Zakariya al-Qazwini.[4]

Sawfish have been found among archaeological remains in several parts of the world, including the Persian Gulf region, the Pacific coast of Panama, coastal Brazil and elsewhere.[4][80]

The cultural significance of sawfish varies significantly. The Aztecs in what is currently Mexico often included depictions of sawfish rostra (saws), notably as the striker/sword of the monster Cipactli.[81] Numerous sawfish rostra have been found buried at the Templo Mayor and two locations in coastal Veracruz had Aztec names referring to sawfish.[4] In the same general region, sawfish teeth have been found in Mayan graves.[82] The saw of sawfish is part of the dancing masks of the Huave and Zapotecs in Oaxaca, Mexico.[4][83] The Kuna people on the Caribbean coast of Panama and Colombia considers sawfish as rescuers of drowning people and protectors against dangerous sea creatures.[8] Also in Panama sawfish were recognized as containing powerful spirits that could protect humans against supernatural enemies.[8]

In the Bissagos Islands off West Africa dancing dressed as sawfish and other sea creatures is part of men's coming-of-age ceremonies.[81][84] In Gambia the saws indicate courage; the more on display at a house the more courageous the owner.[84] In Senegal the Lebu people believe the saw can protect their family, house and livestock. In the same general region they are recognized as ancestral spirits with the saw as a magic weapon. The Akan people of Ghana see sawfish as an authority symbol. There are proverbs with sawfish in the African language Duala.[85] In some other parts of coastal Africa, sawfish are considered extremely dangerous and supernatural, but their powers can be used by humans as their saw retains the powers against disease, bad luck and evil.[85] Among most African groups consumption of meat from sawfish is entirely acceptable, but in a few (in West Africa the Fula, Serer and Wolof people) it is taboo.[84] In the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria, the saws of sawfish (known as oki in Ijaw and neighbouring languages) are often used in masquerades.[86]

In Asia, sawfish are a powerful symbol in many cultures. Asian shamans use sawfish rostrums for exorcisms and in other ceremonies to repel demons and disease.[87] They are believed to protect houses from ghosts when hung over doorways.[4] Illustrations of sawfish are often found at Buddhist temples in Thailand.[82] In the Sepik region of New Guinea locals admire sawfish, but also see them as punishers that will unleash heavy rainstorms on anyone breaking fishing taboos.[8] Among the Warnindhilyagwa, a group of Indigenous Australians, the ancestral sawfish Yukwurrirrindangwa and rays created the land. The ancestral sawfish carved out the river of Groote Eylandt with their saw.[8][88] Among European sailors sawfish were often feared as animals that could sink ships by piercing/sawing in the hull with their saw (claims now known to be entirely untrue),[60] but there are also stories of them saving people. In one case it was described how a ship almost sank during a storm in Italy in 1573. The sailors prayed and made it safely ashore where they discovered a sawfish that had "plugged" a hole in the ship with its saw. A sawfish rostrum said to be from this miraculous event is kept at the Sanctuary of Carmine Maggiore in Naples.[4]

Sawfish have been used as symbols in recent history. During World War II, illustrations of sawfish were placed on navy ships, and used as symbols by both American and Nazi German submarines.[8] Sawfish served as the emblem of the German U-96 submarine, known for its portrayal in Das Boot, and was later the symbol of the 9th U-boat Flotilla. The German World War II Kampfabzeichen der Kleinkampfverbände (Battle Badge of Small Combat Units) depicted a sawfish.

In cartoons and humorous popular culture, the sawfish—particularly its rostrum ("nose")—has been employed as a sort of living tool. Examples of this can be found in Vicke Viking and Fighting Fantasy volume "Demons of the Deep".

A stylized sawfish was chosen by the Central Bank of the West African States to appear on coins and banknotes of the CFA currency. This was due to the mythological value representing fecundity and prosperity. The image takes its form from an Akan and Baoule bronze weight used for exchanges in the commercial trade of gold powder.[84]

Sawfish are popular in public aquariums, but require very large tanks. In a review of 10 North American and European public aquariums that kept sawfish, their tanks were all very large and ranged from about 1,500,000 to 24,200,000 L (400,000–6,390,000 US gal).[55] Individuals in public aquariums often function as "ambassadors" for sawfish and their conservation plight.[90][91] In captivity they are quite robust, appear to grow faster than their wild counterparts (perhaps due to consistent access to food) and individuals have lived for decades, but breeding them has proven difficult.[55] In 2012, four smalltooth sawfish pups were born at Atlantis Paradise Island in the Bahamas and this remains the only time a member of this family has been successfully bred in captivity[55][89] (unsuccessful breeding attempts had happened earlier at the same facility, including a miscarriage in 2003).[92] Nevertheless, it is hoped that this success may be the first step in a captive breeding program for the threatened sawfish.[4] It is speculated that seasonal variations in water temperature, salinity and photoperiod are necessary to encourage breeding.[55] Artificial insemination, as already has been done in a few captive sharks, is also being considered.[93] Tracking studies indicate that if sawfish are released to the wild after spending a period in captivity (for example, if they outgrow their exhibit), they rapidly adopt a movement pattern similar to that of fully wild sawfish.[94]

Among the five sawfish species, only the four Pristis species are known to be kept in public aquariums. The most common is the largetooth sawfish with studbooks including 16 individuals in North America in 2014, 5 individuals in Europe in 2013 and 13 individuals in Australia in 2017, followed by the green sawfish with 13 individuals in North America and 6 in Europe.[55] Both these species are also kept at public aquariums in Asia and the only captive dwarf sawfish are in Japan.[95] In 2014, studbooks included 12 smalltooth sawfish in North America,[55] and the only kept elsewhere are at a public aquarium in Colombia.[95]

Sawfish were once common, with habitat found along the coastline of 90 countries,[96] locally even abundant,[4][7] but they have declined drastically and are now among the most threatened groups of marine fish.[3]

Sawfish and their parts have been used for numerous things. In approximate order of impact, the four most serious threats today are use in shark fin soup, as traditional medicine, rostral teeth for cockfighting spurs and the saw as a novelty item.[4] Despite being rays rather than sharks,[2] sawfish have some of most prized fins for use in shark fin soup, on level with tiger, mako, blue, porbeagle, thresher, hammerhead, blacktip, sandbar and bull shark.[97] As traditional medicine (especially Chinese medicine, but also known from Mexico, Brazil, Kenya, Eritrea, Yemen, Iran, India and Bangladesh) sawfish parts, oil or powder have been claimed to work against respiratory ailments, eye problems, rheumatism, pain, inflammation, scabies, skin ulcers, diarrhea and stomach problems, but there is no evidence supporting any of these uses.[4] The saws are used in ceremonies and as curiosities. Until relatively recently many saws were sold to visiting tourists, or through antique stores or shell shops, but they are now mostly sold online, often illegally.[4] In 2007 it was estimated that the fins and saw from a single sawfish potentially could earn a fisher more than US$5,000 in Kenya and in 2014 a single rostral tooth sold as cockfighting spurs in Peru or Ecuador had a value of up to US$220.[4] Secondary uses are the meat for consumption and the skin for leather.[4] Historically the saws were used as weapons (large saws) and combs (small saws).[88] Oil from the liver was prized for use in boat repairs and street lights,[98] and as recent as the 1920s in Florida it was regarded as the best fish oil for consumption.[4]

Sawfish fishing goes back several thousand years,[7] but until relatively recently it typically involved traditional low-intensity methods such as simple hook-and-line or spearing. In most regions the major population decline in sawfish started in the 1960s–1980s.[7][84][98] This coincided with a major growth in demand of fins for shark fin soup, the expansion of the international shark finning fishing fleet,[84] and a proliferation of modern nylon fishing nets.[98] The exception is the dwarf sawfish which was relatively widespread in the Indo-Pacific, but by the early 1900s it had already disappeared from most of its range, only surviving for certain in Australia (there is a single recent possible record from the Arabian region).[3][99] The saw has been described as sawfish's Achilles' heel, as it easily becomes entangled in fishing nets.[100] Sawfish can also be difficult or dangerous to release from nets, meaning that some fishers will kill them even before bringing them aboard the boat,[56] or cut off the saw to keep it/release the fish. Because it is their main hunting device, the long-term survival of saw-less sawfish is highly questionable.[101] In Australia where sawfish have to be released if caught, the narrow sawfish has the highest mortality rate,[68] but it is still almost 50% for dwarf sawfish caught in gill nets.[99] In an attempt of lowering this, a guide to sawfish release has been published.[102]

Although fishing is the main cause of the drastic decline in sawfish, another serious problem is habitat destruction. Coastal and estuarine habitats, including mangrove and seagrass meadows, are often degraded by human developments and pollution, and these are important habitats for sawfish, especially their young.[4][103] In a study of juvenile sawfish in Western Australia's Fitzroy River about 60% had bite marks from bull sharks or crocodiles.[104] Changes to river flows, such as by dams or droughts, can increase the risk faced by sawfish young by bringing them into more contact with predators.[69][105][106]

The combined range of the five sawfish species encompassed 90 countries, but today they have certainly disappeared entirely from 20 of these and possibly disappeared from several others.[3] Many more have lost at least one of their species, leaving only one or two remaining.[3] Of the five species of sawfish, three are critically endangered and two are endangered according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species.[107] The sawfish is now presumed extinct in 55 nations (including China, Iraq, Haiti, Japan, Timor-Leste, EL Salvador, Taiwan, Djibouti and Brunei), with 18 countries with at least one species of sawfish missing and 28 countries with at least two.[107] The United States and Australia appear to be the last strongholds of the species, where sawfish are better protected.[107] Science Advances identifies Cuba, Tanzania, Colombia, Madagascar, Panama, Brazil, Mexico and Sri Lanka as the nations where urgent action could make a big contribution to saving the species.[107]

The only remaining stronghold of the four species in the Indo-Pacific region (narrow, dwarf, largetooth and green sawfish) is in Northern Australia, but they have also experienced a decline there.[4][71] Pristis sawfish are protected in Australia and only Indigenous Australians can legally catch them.[103][108] Violations can result in a fine of up to AU$121,900.[13] The narrow sawfish does not receive the same level of protection as the Pristis sawfish.[103][109] Under CITES regulations, Australia was the only country that could export wild-caught sawfish for the aquarium trade from 2007 to 2013 (no country afterwards).[21] This strictly involved the largetooth sawfish where the Australian population remains relatively robust, and only living individuals "to appropriate and acceptable aquaria for primarily conservation purposes".[21] Numbers traded were very low (eight between 2007 and 2011),[4] and following a review Australia did not export any after 2011.[21]

Largetooth sawfish have been monitored in Fitzroy River, Western Australia, a primary stronghold for the species, since 2000. In December 2018, the largest recorded mass fish death in the river occurred when more than 40 sawfish died, mainly because of heat and a severe lack of rainfall during a poor wet season.[106] A 14-day research expedition in Far North Queensland in October 2019 did not spot a single sawfish. Expert Dr Peter Kyne of Charles Darwin University said that habitat change in the south and gillnet fishing in the north had contributed to the decline in numbers, but now that fishers had started working with the conservationists, dams and water diversions to the river flows had become a bigger problem in the north. Also, impact of successful saltwater crocodile conservation is a negative one on sawfish populations. However, there were still good populations in the Adelaide River and Daly River in the Northern Territory, and the Fitzroy River in the Kimberley.[110]

A study by Murdoch University researchers and Indigenous rangers, which captured more than 500 sawfish between 2002 and 2018, concluded that the survival of the sawfish could be at risk from dams or major water diversions on the Fitzroy River. It found that the fish are completely reliant on the Kimberley's wet season floods to complete their breeding cycle; in recent drier years, the population has suffered. There has been debate about using water from the river for agriculture and to grow fodder crops for cattle in the region.[111]

Sharks and Rays Australia (SARA) are conducting a citizen science investigation to understand the sawfish's historical habitats. Citizen can report their sawfish sighting online.[112]

Except for Australia, sawfish have been extirpated or only survive in very low numbers in the Indo-Pacific region. For example, among the four species only two (narrow and largetooth sawfish) certainly survive in South Asia, and only two (narrow and green sawfish) certainly survive in Southeast Asia.[3]

The status of the two species of the Atlantic region, the smalltooth and largetooth sawfish, is comparable to the Indo-Pacific. For example, sawfish have been entirely extirpated from most of the Atlantic coast of Africa (only survives for certain in Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone), as well as South Africa.[3][113] The only relatively large remaining population of the largetooth sawfish in the Atlantic region is at the Amazon estuary in Brazil, but there are smaller in Central America and West Africa, and this species is also found in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.[114] The smalltooth sawfish is only found in the Atlantic region and it is possibly the most threatened of all the species, as it had the smallest original range (range c. 2,100,000 km2 or 810,000 sq mi) and has experienced the greatest contraction (disappeared from c. 81% of its original range).[4] It only survives for certain in six countries,[115] and it is possible that the only remaining viable population is in the United States.[100] In the United States the smalltooth sawfish once occurred from Texas to New York, but its numbers have declined by at least 95% and today it is essentially restricted to Florida.[116][117] However, the Florida population retains a high genetic diversity,[116] has now stabilised and appears to be slowly increasing.[82][117] A Recovery Plan for the smalltooth sawfish has been in effect since 2002.[103] It has been strictly protected in the United States since 2003 when it was added to the Endangered Species Act as the first marine fish.[118] This makes it "illegal to harm, harass, hook, or net sawfish in any way, except with a permit or in a permitted fishery".[14] The fine is up to US$10,000 for the first violation alone.[14] If accidentally caught, the sawfish has to be released as carefully as possible and a basic how-to guide has been published.[14] In 2003 an attempt of adding the largetooth sawfish to the Endangered Species Act was denied, in part because this species does not occur in the United States anymore[118] (last confirmed US record in 1961).[114] However, it was added in 2011,[119] and all the remaining sawfish species were added in 2014, restricting trade in them and their parts in the United States.[36] In 2020, a Florida fisherman used a power saw to remove a smalltooth sawfish's rostrum and then released the maimed fish; he received a fine, community service and probation.[120]

Since 2007, all sawfish species have been listed on CITES Appendix I, which prohibits international trade in them and their parts.[11][12][121] The only exception was the relatively robust Australian population of the largetooth sawfish that was listed on CITES Appendix II, which allowed trade to public aquariums only.[11] Following reviews Australia did not use this option after 2011 and in 2013 it too was moved to Appendix I.[21] In addition to Australia and the United States, sawfish are protected in the European Union, Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Guinea, Senegal and South Africa, but they are likely already functionally extirpated or entirely extirpated from several of these countries.[3][7][122][123] Illegal fishing continues and in many countries enforcement of fishing laws is lacking.[3][21] Even in Australia where relatively well-protected, people are occasionally caught illegally trying to sell sawfish parts, especially the saw.[13] The saw is distinctive, but it can be difficult to identify flesh or fins as originating from sawfish when cut up for sale at fish markets. This can be resolved with DNA testing.[124] If protected their relatively low reproduction rates make these animals especially slow to recover from overfishing.[87] An example of this is the largetooth sawfish in Lake Nicaragua where once abundant. The population rapidly crashed during the 1970s when tens of thousands were caught. It was protected by the Nicaraguan government in the early 1980s, but remains rare today.[4] Nevertheless, there are indications that at least the smalltooth sawfish population may be able to recover at a faster pace than formerly believed, if well-protected.[125] Uniquely in this family, the narrow sawfish has a relatively fast reproduction rate (generation length about 4.6 years, less than one-third the time of the other species), it has experienced the smallest contraction of its range (30%) and it is one of only two species considered Endangered rather than Critically Endangered by the IUCN.[3] The other rated as Endangered is the dwarf sawfish, but this primarily reflects that its main decline happened at least 100 years ago and IUCN ratings are based on the time period of the last three generations (estimated about 49 years in dwarf sawfish).[3][99]

There are several research projects aimed at sawfish in Australia and North America, but also a few in other continents.[126] The Florida Museum of Natural History maintains the International Sawfish Encounter Database where people worldwide are encouraged to report any sawfish encounters, whether it was living or a rostrum seen for sale in a shop/online.[4][14][82] Its data is used by biologists and conservationists for evaluating the habitat, range and abundance of sawfish around the world.[4] In an attempt of increasing the knowledge of their plight the first "Sawfish Day" was held on 17 October 2017,[83][127] and this was repeated on the same date in 2018.[128]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) {{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) {{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) {{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Sawfish, also known as carpenter sharks, are a family of rays characterized by a long, narrow, flattened rostrum, or nose extension, lined with sharp transverse teeth, arranged in a way that resembles a saw. They are among the largest fish with some species reaching lengths of about 7–7.6 m (23–25 ft). They are found worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions in coastal marine and brackish estuarine waters, as well as freshwater rivers and lakes. All species are endangered.

They should not be confused with sawsharks (order Pristiophoriformes) or the extinct sclerorhynchoids (order Rajiformes) which have a similar appearance, or swordfish (family Xiphiidae) which have a similar name but a very different appearance.

Sawfishes are relatively slow breeders and the females give birth to live young. They feed on fish and invertebrates that are detected and captured with the use of their saw. They are generally harmless to humans, but can inflict serious injuries with the saw when captured and defending themselves.

Sawfish have been known and hunted for thousands of years, and play an important mythological and spiritual role in many societies around the world.

Once common, sawfish have experienced a drastic decline in recent decades, and the only remaining strongholds are in Northern Australia and Florida, United States. The five species are rated as Endangered or Critically Endangered by the IUCN. They are hunted for their fins (shark fin soup), use of parts as traditional medicine, their teeth and saw. They also face habitat loss. Sawfish have been listed by CITES since 2007, restricting international trade in them and their parts. They are protected in Australia, the United States and several other countries, meaning that sawfish caught by accident have to be released and violations can be punished with hefty fines.

Segilofiŝoj (biologie latine pristidae laŭ la greka vorto „pristis“ = segilo, do faktermine ankaŭ nomeblaj pristedoj, neformale nomataj segilorajoj) estas la nura familio de la ordo de pristoformaj. Segilofiŝoj havas longecan korpon iom similan al ŝarkoj. Plej elstara karakterizaĵo de la segilofiŝoj estas kartilaga "korno" pinte de la kapo, kiu kutime ampleksas pli ol kvaronon de la tuta fiŝa longo kaj flanke havas multajn "segilajn" dentojn. Tiu segilo servas al kaptado de manĝaĵo: La segilofiŝo naĝas en fiŝarojn kaj tiam rapide movas la segilon dekstren kaj maldekstren, en provo vundi iujn fiŝojn kaj poste manĝi la vunditajn viktimojn. Krome la segiloj uzatas por manĝocele serĉi krustacojn en ŝlima grundo, kaj krome ankaŭ havas elektromagnetajn receptorojn por trovo de ĉaseblaj marbestoj.

Los pristiformes (del lat. pristis, "pez sierra") son un orden de elasmobranquios del superorden Batoidea, conocidos vulgarmente como peces sierra. Incluyen una sola familia, Pristidae, con dos géneros y siete especies.[2]

Los peces sierra están más relacionados con las rayas que con los tiburones. Su apariencia es la de un pez con un hocico largo y lleno de dientes. Poseen un esqueleto cartilaginoso.

No deben ser confundidos con los tiburones sierra (orden Pristiophoriformes), que tienen una apariencia similar.

Las dimensiones de los peces sierra van de 1,5 m a 6 m. La característica más sobresaliente del pez sierra es, por supuesto, su hocico con forma de sierra. Este se encuentra cubierto con poros sensibles al movimiento y a la electricidad, que les permite detectar el movimiento e incluso los latidos cardíacos de presas enterradas en el sedimento marino. Su hocico actúa entonces como un detector mientras el pez sierra nada sobre el fondo marino, en busca de alimento. Su hocico también sirve como herramienta excavadora para desenterrar crustáceos.

Cuando una presa nada cerca, el pez sierra ataca desde abajo y utiliza furiosamente su sierra. Esto generalmente hiere a la presa lo suficiente para que el pez la devore sin mucha dificultad. Los peces sierra también utilizan su hocico como arma de defensa contra otros depredadores como tiburones, delfines y buzos intrusos. Los dientes que sobresalen del hocico no son verdaderos dientes, sino escamas dentales modificadas.

El cuerpo y la cabeza de los peces sierra son aplanados ya que pasan la mayoría del tiempo recostados en el suelo marino. Al igual que las rayas, su boca está localizada en su parte inferior. En su boca existen pequeños dientes para comer pequeños crustáceos y otros peces, aunque a veces los devora enteros.

Los peces sierra respiran por dos espiráculos localizados detrás de sus ojos que conducen el agua a las branquias. Su piel está cubierta por pequeños dentículos que le dan una textura rasposa. Su color es generalmente gris o café, aunque la especie Pristis pectinata es color verde oliva.

Los ojos de los peces sierra no están muy desarrollados por su hábitat lodoso. Su hocico es su principal herramienta sensorial. Sus intestinos tienen forma de sacacorchos.

Los peces sierra se localizan en áreas Zona intertropical tropicales y subtropicales alrededor de África, Australia y el Caribe. Los peces sierra viven en aguas poco profundas y lodosas, en aguas saladas y dulces. La mayoría prefiere bocas de río y sistemas de agua dulce. Todos los peces sierra tienen la habilidad de cambiar de aguas saladas a aguas dulces, y generalmente lo hacen, nadando dentro de ríos, así como en bahías y estuarios.

Son nocturnos; usualmente duermen durante el día y cazan a la noche. A pesar de las apariencias, son peces que no atacan a las personas a menos que sean provocados o sorprendidos.

Poco se conoce sobre la reproducción del pez sierra. Cada individuo vive entre 25 y 30 años, madurando a los 10.

Maduran lentamente; se estima que no se reproducen hasta que alcanzan entre 3,5 y 4 metros de largo y tienen entre 10 y 12 años de edad, y se reproducen a niveles inmensamente menores que la mayoría de los peces. Esto hace que a estos animales les cueste demasiado recuperarse, en especial tras una sobrepesca.

Los pristiformes (del lat. pristis, "pez sierra") son un orden de elasmobranquios del superorden Batoidea, conocidos vulgarmente como peces sierra. Incluyen una sola familia, Pristidae, con dos géneros y siete especies.

Los peces sierra están más relacionados con las rayas que con los tiburones. Su apariencia es la de un pez con un hocico largo y lleno de dientes. Poseen un esqueleto cartilaginoso.

No deben ser confundidos con los tiburones sierra (orden Pristiophoriformes), que tienen una apariencia similar.

Zerra-arrainak itsas-arrain selazeoak dira, Pristidae familia osatzen dutenak. Gorputz zapala dute eta zerra itxurako muturra. Genero bakarra hartzen du familia horrek, Pristis izenekoa. Sarritan aurkitzen dira kostako itsasaldeetan, batez ere ur epel eta tropikaletan. Askotan ibaietan barneratzen dira.[1]

Pristis clavata

Pristis clavata Pristis pectinata

Pristis pectinata Pristis zijsron

Pristis zijsronZerra-arrainak itsas-arrain selazeoak dira, Pristidae familia osatzen dutenak. Gorputz zapala dute eta zerra itxurako muturra. Genero bakarra hartzen du familia horrek, Pristis izenekoa. Sarritan aurkitzen dira kostako itsasaldeetan, batez ere ur epel eta tropikaletan. Askotan ibaietan barneratzen dira.

Saharauskukalat (Pristiformes) on rustokalalahko. Lahkoon kuuluu vain yksi heimo saharauskut (Pristidae).

Sahahaikaloihin kuuluvien lajien fossiileista vanhimmat on ajoitettu liitukauden keski- ja myöhäisvaiheille. Nykyään heimoon kuuluu seitsemän lajia, jotka jaetaan kahteen sukuun.[3][4][5][6] Lajit ovat[7]: