en

names in breadcrumbs

Barasinghas react to the alarm calls of their own kind as well as those of other animals by holding their necks erect and cocking their ears, facing themselves towards the threat. This alerts others in the herd, who adopt the same posture as well as raise their tails and stomp their hooves. Barks and screams are sent back and forth throughout the herd, rising in pitch if a predator is sighted. The alarm reaction persists until the barasinghas are certain danger is no longer near. The primary natural predators of barasinghas are tigers and leopards.

Known Predators:

Adult Rucervus duvaucelii stand between 119 to 124 centimeters at the shoulder, and weigh approximately 172 to 181 kilograms. Their coats are chestnut brown on the back, fading to a lighter brown on the sides and belly, with a creamy white on the inside of the legs, rump, and underside of the tail. Their chins, throats, and the insides of their ears are also whitish in color. In winter months, beginning around November, the coat turns a dark, dull grayish brown. Adult males will have darker coats than females and juveniles, ranging from dark brown to almost black. The coats of fawns are brown and spotted when born, but the spots will fade as the fawn matures.

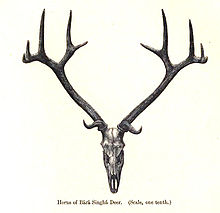

The name “barasingha” literally means “twelve-tined”. A fully adult male can have 10 to 15 tines, though some males have been found to have up to 20. Antlers of barasingha are smooth, the main beam sweeping upward for over half the length before branching repeatedly.

Range mass: 172 to 181 kg.

Range length: 119 to 124 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger; sexes colored or patterned differently; ornamentation

The oldest captive Rucervus duvaucelii reached 23 years of age; in the wild, individuals typically reach 20 years old.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 20 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 23 years.

The name “swamp deer” refers to the habitat preferred by the species. Rucervus duvaucelii duvaucelii is found in swampland and a variety of forest types ranging from dry to moist deciduous to evergreen. Rucervus duvaucelii branderi is found in grassy floodplains. In either forested or open habitats, both subspecies are commonly found near bodies of water.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; forest

Wetlands: marsh ; swamp ; bog

Other Habitat Features: riparian

Texts disagree on the number of subspecies of the barasingha. Some sources name a third subspecies, R. d. ranjitsinhi, found in Assam, India, though this taxonomy is not universally accepted.

Barasinghas were previously known by the scientific name Cervus duvaucelii, this was recently changed to Rucervus duvaucelii.

Barasingha males use wallows to spread their scent during the rut in an attempt to attract available females and announce their presence to other males. Bugles and barks are also employed for these purposes. Alarm calls are used when predators are nearby.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Barasinghas are listed as an endangered species by the IUCN. The subspecies R. d. duvaucelii is considered a vulnerable species, while R. d. branderi is endangered. Degradation of habitat, along with predation and hunting has brought barasinghas to low population levels.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: appendix i

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: vulnerable

Barasinghas are shot and killed because they are thought to feed on crops, although there is no evidence to support this assumption.

Barasinghas that leave protected lands are hunted for food by humans.

Positive Impacts: food

Barasinghas are an important prey animal for tigers and leopards. They graze heavily on grasses and impact plant communities.

Ecosystem Impact: disperses seeds

Barasinghas primarily eat grasses. During the hot season, they will drink at least twice a day, the first time soon after daylight and again in the late afternoon.

Plant Foods: leaves; flowers

Primary Diet: herbivore (Folivore )

Barasingha, or swamp deer (Rucervus duvaucelii), were once distributed throughout the Indian peninsula, but today are only found in areas of central and northern India and southern Nepal. There are two recognized subspecies: R. d. branderi, found in Madhya Pradesh, and R. d. duvaucelii, found in Uttar Pradesh and southern Nepal.

Biogeographic Regions: oriental (Native )

Barasingha are polygynous, a dominant stag collecting a harem of up to thirty hinds (females). He will fight with other males for possession of the harem and the right to breed. At the beginning of the rut in mid-October, herds start to break apart and males create wallows. Male barasingha wallow by urinating and defecating in muddy pools and then roll, coating themselves in scent. Males also begin to bugle and bark; these sounds are sometimes compared to the braying of mules. Their calls will continue throughout the rut and well into February. Fights between competing males occur as they form harems. Males will scrape the ground with their hooves and then run at each other, clashing antlers. The tines will often be snapped off during these fights, leaving the antlers broken or disfigured. At the end of the rut, stags will leave their females and band together with other stags, while hinds form herds with similarly-aged females.

Mating System: polygynous

Breeding, or rutting, season begins in October and continues through February. The gestation period lasts 240 to 250 days, with most fawns born between September and October. A female barasingha reaches sexual maturity at 2 years of age. Barasinghas have one fawn per year, rarely twins.

Breeding interval: Barasinghas breed once a year.

Breeding season: Breeding occurs from October through February.

Range number of offspring: 1 to 2.

Average number of offspring: 1.

Range gestation period: 8 to 8.33 months.

Range weaning age: 6 to 8 months.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 2 to 3 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; viviparous

A female barasingha will wean her young between 6 to 8 months of age. Males are not involved in providing for or protecting the young.

Parental Investment: precocial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female)

The barasingha (Rucervus duvaucelii), also known as the swamp deer, is a deer species distributed in the Indian subcontinent. Populations in northern and central India are fragmented, and two isolated populations occur in southwestern Nepal. It has been extirpated in Pakistan and Bangladesh, and its presence is uncertain in Bhutan.[1]

The specific name commemorates the French naturalist Alfred Duvaucel.[3]

The swamp deer differs from all other Indian deer species in that the antlers carry more than three tines. Because of this distinctive character it is designated bārah-singgā, meaning "twelve-horned" in Hindi.[4] Mature stags usually have 10 to 14 tines, and some have been known to have up to 20.[5]

In Assamese, barasingha is called dolhorina; dol meaning swamp.

The barasingha is a large deer with a shoulder height of 44 to 46 in (110 to 120 cm) and a head-to-body length of nearly 6 ft (180 cm). Its hair is rather woolly and yellowish brown above but paler below, with white spots along the spine. The throat, belly, inside of the thighs and beneath the tail is white. In summer, the coat becomes bright rufous-brown. The neck is maned. Females are paler than males. Young are spotted. Average antlers measure 30 in (76 cm) round the curve with a girth of 5 in (13 cm) at mid beam.[6] A record antler measured 104.1 cm (41.0 in) round the curve.[5]

Stags weigh 170 to 280 kg (370 to 620 lb). Females are less heavy, weighing about 130 to 145 kg (287 to 320 lb).[7] Large stags have weighed from 460 to 570 lb (210 to 260 kg).[4]

Swamp deer were common in many areas, including parts of the Upper Narmada valley and to the south in Bastar, during the 19th century.[6] They frequent flat or undulating grasslands and generally keep in the outskirts of forests. Sometimes, they are also found in open forest.[4]

In the 1960s, the total population was estimated at 1,600 to less than 2,150 individuals in India and about 1,600 in Nepal. Today, the distribution is much reduced and fragmented due to major losses in the 1930s–1960s following unregulated hunting and conversion of large tracts of grassland to cropland. Swamp deer occur in the Kanha National Park of Madhya Pradesh, in two localities in Assam, and in only 6 localities in Uttar Pradesh. They are regionally extinct in West Bengal.[8] They are also probably extinct in Arunachal Pradesh.[9] A few survive in Assam's Kaziranga and Manas National Parks.[10][11][12][13] In 2005, a small population of about 320 individuals was discovered in the Jhilmil Jheel Conservation Reserve in Haridwar district in Uttarakhand on the east bank of the Ganges. This represents the northern limit of the species.[14][15]

Three subspecies are currently recognized:[16]

Swamp deer are mainly grazers.[4] They largely feed on grasses and aquatic plants, foremost on Saccharum, Imperata cylindrica, Narenga porphyrocoma, Phragmites karka, Oryza rufipogon, Hygroryza and Hydrilla. They feed throughout the day with peaks during the mornings and late afternoons to evenings. In winter and monsoon, they drink water twice, and thrice or more in summer. In the hot season, they rest in the shade of trees during the day.[8]

In central India, the herds comprise on average about 8–20 individuals, with large herds of up to 60. There are twice as many females than males. During the rut they form large herds of adults. The breeding season lasts from September to April, and births occur after a gestation of 240–250 days in August to November. The peak is in September and October in Kanha National Park.[7] They give birth to single calves.[7]

When alarmed, they give out shrill, baying alarm calls.[5]

Compared to other deer species, Barasingha are more relaxed when it comes to guarding. They have fewer sentries and they spend most of their time grazing, unlike deer species like Spotted deer or Sambar deer.[22]

The swamp deer populations outside protected areas and seasonally migrating populations are threatened by poaching for antlers and meat, which are sold in local markets. Swamp deer lost most of its former range because wetlands were converted and used for agriculture so that suitable habitat was reduced to small and isolated fragments.[8] The remaining habitat in protected areas is threatened by the change in river dynamics, reduced water flow during summer, increasing siltation, and is further degraded by local people who cut grass, timber and fuelwood,[1] and by illegal farming on government land.[23]

George Schaller wrote: "Most of these remnants have or soon will have reached the point of no return."[7]

Rucervus duvaucelii is listed on CITES Appendix I.[1] In India, it is included under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972.[8]

In 1992, there were about 50 individuals in five Indian zoos and 300 in various zoos in North America and Europe.[8]

Swamp deer were introduced to Texas.[24] They exist only in small numbers on ranches.[25]

Rudyard Kipling in The Second Jungle Book featured a barasingha in the chapter "The Miracle of Purun Bhagat" by the name of "barasingh". It befriends Purun Bhagat because the man rubs the stag's velvet off his horns. Purun Bhagat then gives the barasinga nights in the shrine at which he is staying, with his warm fire, along with a few fresh chestnuts every now and then. Later as pay, the stag warns Purun Bhagat and his town about how the mountain on which they live is crumbling.

Barasingha is the state animal of the Indian states of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh.[26]

The barasingha (Rucervus duvaucelii), also known as the swamp deer, is a deer species distributed in the Indian subcontinent. Populations in northern and central India are fragmented, and two isolated populations occur in southwestern Nepal. It has been extirpated in Pakistan and Bangladesh, and its presence is uncertain in Bhutan.

The specific name commemorates the French naturalist Alfred Duvaucel.

The swamp deer differs from all other Indian deer species in that the antlers carry more than three tines. Because of this distinctive character it is designated bārah-singgā, meaning "twelve-horned" in Hindi. Mature stags usually have 10 to 14 tines, and some have been known to have up to 20.

In Assamese, barasingha is called dolhorina; dol meaning swamp.