en

names in breadcrumbs

Cirripedia, the barnacles, make up an infraclass of arthropods (although they are sometimes considered a class or subclass) with about 1000 species.They are exclusively marine organisms, well-represented in the fossil record back to the Cambrian (500 million years ago), very diverse and abundant, and found in just about every marine environment, from shallow and tidal waters to deep sea abyss.

As adults, most barnacles are sessile suspension feeders; they pump the current with six biramous thoracic appendages, a feature they are named for: Cirripedia is Latin for curled foot.The most highly modified of the arthropods, barnacles generally secrete a calcareous carapace; in fact Linnaeas originally classified the barnacles as molluscs for this reason.

Most adult barnacles filter feed from hard substrates, upon which they glue their shells directly or attach from a stalk, or form burrows in mollusc shells or coral skeletons with a scute across the opening. Some species are parasites, such as barnacles in order Rhizocephala which live on other crustaceans, especially decapods. The adult phase of parasitic barnacles usually has a derived morphology specialized for its lifestyle, and far simpler than that of free-living barnacles.These parasites are essentially an unsegmented sac-like body with no appendages, no carapace, and thin rhizomes for extending into the body of their host to feed.While these adult stages are so diverse as to share almost no features with free-living adult species, barnacles are united by the morphologies of their larval stages, especially the nauplus stage.

Barnacles are one of the better-known marine invertebrates, since they are water-foulers, attaching to ships and other structures where they can cause damage.Some species are eaten as a delicacy, such as gooseneck barnacles, e.g. Pollicipes cornucopia harvested for consumption especially for the Spanish market, where they are called percebes) and acorn barnacles, such as the giants Austromegabalanus psittacus (called picoroco in Chilean cuisine) and Balanus nubilus, the world’s largest barnacle at up to 3 inches across which is endemic to the Pacific coast of North America and traditionally eaten by Native Americans.

(Kozloff 1990; Newman and Abbott 1980; The Oregon Coast Aquarium 2014; Wikipedia 2013)

Bığayaqlılar (lat. Cirripedia) — Xərçəngkimilər yarımtipinin Çənəayaqlılar sinfinə aid infrasinif. 1220 növü məlumdur.

Bığayaqlılar (lat. Cirripedia) — Xərçəngkimilər yarımtipinin Çənəayaqlılar sinfinə aid infrasinif. 1220 növü məlumdur.

Els cirrípedes (Cirripedia) formen part d'una de les 3 infraclasses dels tecostracis que comprenen els peus de cabrit o percebes, de gran interès gastronòmic, i les glans de mar.

Reben llur nom a causa dels cirrus o membres amb forma de plomall que projecten fora del cos amb l'objectiu d'atrapar detritus com a part de llur nutrició.

Són crustacis molt modificats i, per tant, tenen una relació llunyana amb crancs i llagostes. Els peus de cabrit ja varen ser estudiats i classificats per Charles Darwin que publicà una sèrie de monografies el 1851 i el 1854.

Els cirrípedes tenen dos tipus corporals bàsics: amb peduncle i sense peduncle. Els que no tenen peduncle es troben normalment per tot el litoral rocós, mentre que els pedunculats prefereixen viure mar endins o sobre objectes flotants. A més d'aquests dos tipus bàsics, existeix un tercer tipus de morfologia una mica diferent, els "amorfs" o verrucomorfa. Aquests últims no són simètrics i viuen en aigües profundes, generalment sobre les espines d'eriçons (vegeu Echinoidea) o com a paràsits de crancs i de balenes.

Els cirrípedes tenen dues etapes larvals:

Els adults tenen sis plaques externes a tall d'armadura. Durant la resta de la seva vida són sèssils i s'alimenten filtrant plàncton amb els seus apèndixs i alliberant els seus gàmetes. Se'ls sol trobar a la zona intermareal.

Un cop completada la metamorfosi i assolida la forma adulta, continuen creixent, però no sofreixen mudes i creixen per addició de material a la seva coberta calcificada.

Com molts altres invertebrats, els cirrípedes són hermafrodites i alternen l'estat masculí i femení temporalment: és a dir, existeix un estat unisexual altern, o, el que és el mateix, un individu pot ser inicialment mascle i després femella, i viceversa. Quant a la morfologia de l'òrgan reproductor, els percebes ostenten el rècord de mida de penis en relació a la llargada del seu cos, el més llarg de tot el regne animal.[1]

Existeixen uns cirrípedes amb una biologia molt diferent, i és el cas dels rizocèfals, que són paràsits dels crancs.

La seva peculiar morfologia va fer que fa dos segles es confonguessin amb mol·luscs. De fet, molts dels noms que se li donen a diferents parts del seu cos responen a aquesta antiga creença: mantell, plaques... Tanmateix, en estudiar les seves larves es va veure que eren cipris, similars a les d'ostrácodos, el que va ser clau per a estudis posteriors que van concloure que es tractava de crustacis amb una morfologia "aberrant".

Seguint la proposta de Martin i Davis,[2] es considera els cirrípedes (Cirripedia) (Burmeister, 1834) com una infraclasse subdividida en tres superordres, cadascun amb dos ordres:

Estan descrites unes 1.220 espècies. Alguns especialistes consideren els Cirripedia com una classe o una subclasse, i les ordres llistats aquí considerats com a ordres són, a vegades, tractats com superordres.

Els cirrípedes (Cirripedia) formen part d'una de les 3 infraclasses dels tecostracis que comprenen els peus de cabrit o percebes, de gran interès gastronòmic, i les glans de mar.

Reben llur nom a causa dels cirrus o membres amb forma de plomall que projecten fora del cos amb l'objectiu d'atrapar detritus com a part de llur nutrició.

Són crustacis molt modificats i, per tant, tenen una relació llunyana amb crancs i llagostes. Els peus de cabrit ja varen ser estudiats i classificats per Charles Darwin que publicà una sèrie de monografies el 1851 i el 1854.

Mae gwyran' (llusog: gwyrain) ac a elwir weithiau'n 'ŵydd môr' a 'chragen long') yn fath o arthropod a ffurfia'r grŵp Cirripedia yn yr is-ffylwm Cramenogion, ac mae'n perthyn felly i grancod a chimychod.

Ceir gwyrain yn byw yn y môr yn unig - mewn dyfroedd bas a llanwol. Ceir tua 1,220 rhywogaeth o wyrain.

Mae'r enw 'Cirrypedia' yn Lladin yn golygu "troed cyrliog".[1]

Ceir ffosilod gwyrain sy'n dyddio i'r 'Cyfnod Cambraidd Canol' (sef tua 510 i 500 miliwn o flynyddoedd yn ôl).

Bwyteir gwyrain mewn diwylliannau ledled y byd megis Portwgal a Siapan.

Mae gwyran' (llusog: gwyrain) ac a elwir weithiau'n 'ŵydd môr' a 'chragen long') yn fath o arthropod a ffurfia'r grŵp Cirripedia yn yr is-ffylwm Cramenogion, ac mae'n perthyn felly i grancod a chimychod.

Ceir gwyrain yn byw yn y môr yn unig - mewn dyfroedd bas a llanwol. Ceir tua 1,220 rhywogaeth o wyrain.

Svijonožci (Cirripedia) jsou skupina korýšů z třídy Maxillopoda. Jsou to přisedlí korýši, kteří se usazují na exponovaných skalách, molech a pontonech. Zatímco většina jejich larválních forem žije na kůži velryb či želv, zvláštní paraziti kořenohlavci (Rhizocephala) žijí ve vnitřnostech krabů. Největší druhy svijonožců žijí ve stále zatopené zóně mořského dna.

Měkké tělíčko přikrývá korunka čtyř nebo šesti vápenitých desek. Na otvoru jsou dva páry uzavíracích destiček, které svijonožce chrání po dobu odlivu před vyschnutím.

Vzhledem k přisedlému způsobu života se tito tvorové zvlášť přizpůsobili k přijímání potravy. Obrovské vějíře, které dohromady tvoří hustý koš, filtrují rytmickým máváním z vody mikroorganismy a jiné volně se vznášející potravní částečky.

Základní monografii o svijonožcích vypracoval Charles Darwin.

Svijonožci (Cirripedia) jsou skupina korýšů z třídy Maxillopoda. Jsou to přisedlí korýši, kteří se usazují na exponovaných skalách, molech a pontonech. Zatímco většina jejich larválních forem žije na kůži velryb či želv, zvláštní paraziti kořenohlavci (Rhizocephala) žijí ve vnitřnostech krabů. Největší druhy svijonožců žijí ve stále zatopené zóně mořského dna.

Rankefødder (latin Cirripedia) er små krebsdyr.

Rankefødder omfatter bl.a.:

Rankefødder lever i havet, ofte i kystzonen hvor de fæstner sig til en hård overflade. De fleste arter (bl.a. rurer) lever af plankton eller andet organisk materiale i vandet.

Rodkrebs, nogle gang kaldet "zombie-parasit" er parasitter. Som larve fæster den sig på andre krebsdyr, fx en strandkrabbe, og leder efter en åbning i krabbens skal. Der sniger rodkrebsen sig ind, og begynder at danne tråde, som den trækker op i krabbens hoved. Der overtager rodkrebsens netværk krabbens hjerne og får krabben til at tro, at den er gravid, og at rodkrebsen er dens afkom. Dernæst danner rodkrebsen en ballon på krabbens mave, hvor krabbens æg ville have siddet. Normalt ville krabben prøve at fjerne parasitten; men da den nu er overbevist om, at rodkrebsen er dens eget afkom, passer krabben på, at rodkrebsen har det godt, fjerner alger fra den osv. Rodkrebsen trækker også sine tråde omkring krabbens tarme, og forsyner sig af krabbens mad. Krabben får kun lige nok til, at den kan overleve. [1]

Rankefødder (latin Cirripedia) er små krebsdyr.

Rankefødder omfatter bl.a.:

Rurer (eller balaner) Rodkrebs (Rhizocephala)Rankefødder lever i havet, ofte i kystzonen hvor de fæstner sig til en hård overflade. De fleste arter (bl.a. rurer) lever af plankton eller andet organisk materiale i vandet.

Rodkrebs, nogle gang kaldet "zombie-parasit" er parasitter. Som larve fæster den sig på andre krebsdyr, fx en strandkrabbe, og leder efter en åbning i krabbens skal. Der sniger rodkrebsen sig ind, og begynder at danne tråde, som den trækker op i krabbens hoved. Der overtager rodkrebsens netværk krabbens hjerne og får krabben til at tro, at den er gravid, og at rodkrebsen er dens afkom. Dernæst danner rodkrebsen en ballon på krabbens mave, hvor krabbens æg ville have siddet. Normalt ville krabben prøve at fjerne parasitten; men da den nu er overbevist om, at rodkrebsen er dens eget afkom, passer krabben på, at rodkrebsen har det godt, fjerner alger fra den osv. Rodkrebsen trækker også sine tråde omkring krabbens tarme, og forsyner sig af krabbens mad. Krabben får kun lige nok til, at den kan overleve.

Die Rankenfußkrebse (Cirripedia) sind eine Teilklasse der Krebstiere (Crustacea). Insgesamt sind etwa 800 Arten bekannt, die alle marin leben. Adulte Tiere leben sessil im oder am Wasser oder parasitisch an anderen Tieren.

Rankenfußkrebse besitzen keine Gliedmaßen, der Hinterleib ist reduziert, der Körper ist kurz und gedrungen. Ursprünglich besteht der Thorax aus sechs Segmenten, an denen je ein Spaltbeinpaar ausgebildet ist. Die Spaltbeine, die aus beborsteten Gliedmaßen (Cirren) bestehen, sind für die Fortbewegung ungeeignet. Bei parasitisch lebenden Tieren sind diese vollständig zurückgebildet. Den Körper umschließt ein aus zwei Teilen bestehender Carapax oder Mantel. Bei sessilen Lebensformen bilden sich typische Kalkplatten aus, die ein festes Außengehäuse (Mauerkrone) bilden können.

Rankenfußkrebse sind in der Regel zweigeschlechtlich (Zwitter). Bei getrenntgeschlechtlichen Arten sind die Männchen extrem klein (Zwergmännchen) und befinden sich am Carapax des Weibchens.

Aus dem befruchteten Ei entwickelt sich eine Naupliuslarve, eine einäugige Larve, bestehend aus einem Kopf und einem Telson, ohne Thorax und Abdomen. Die Naupliuslarve verbringt die erste Zeit im Carapax des Weibchens.

Nach einiger Zeit verlässt die Larve den Carapax. Dieses Metanauplius genannte Larvenstadium ist eine Übergangsform und entwickelt sich weiter zur Cyprislarve.[1][2]

Die Cyprislarve ist das letzte Larvenstadium vor der adulten Form. Diese weist erstaunliche Ähnlichkeit mit dem Muschelkrebs auf. Das Cyprisstadium dient nicht der Nahrungsaufnahme, sein Zweck ist es, einen geeigneten Platz zum Ansiedeln zu finden, da die adulten Tiere sesshaft sind.[1] Das Cyprisstadium dauert einige Tage bis Wochen. Die Larve kundschaftet mit modifizierten Antennen potentielle Oberflächen aus, sie bewerten dabei die Oberflächen auf der Grundlage ihrer Oberflächentextur, ihrer Chemie, Benetzbarkeit, Farbe und – wenn vorhanden – der Zusammensetzung eines Oberflächenbiofilms. Schwärmende Arten setzen sich auch eher in der Nähe anderer Seepocken fest. Wenn die Suche lange dauert und die Energiereserven knapper werden, wird die Larve weniger wählerisch. Hat sie eine potentiell geeignete Stelle gefunden, heftet sie sich mit ihren Antennen und einer abgesonderten Glykoprotein-Substanz mit dem Vorderkopf (also kopfüber) an die feste Unterlage an, um sich vollständig in ein adultes Tier zu entwickeln.[3]

In Portugal und Teilen Spaniens gelten die zur Klasse der Rankenfußkrebse zählenden Entenmuscheln (Pollicipes pollicipes) als Delikatesse. Die dort unter dem Namen percebes angebotenen Tiere sind bei Gourmets als recht teure Spezialität beliebt.

Charles Darwin führte vor der Abfassung seines Hauptwerks Über die Entstehung der Arten mehrere Jahre lang Untersuchungen an Rankenfußkrebsen durch. Er nutzte sie als Modellgruppe für das Hervorgehen von Arten aus anderen Arten durch Evolution.[4]

Die Rankenfußkrebse (Cirripedia) sind eine Teilklasse der Krebstiere (Crustacea). Insgesamt sind etwa 800 Arten bekannt, die alle marin leben. Adulte Tiere leben sessil im oder am Wasser oder parasitisch an anderen Tieren.

Is urrainn do "bàirneach" a' ciallachadh copan Moire

Tha bàirneach neo bàrnach na sheòrsa maorach geal a cheanglas e fhèin gu teann ri creagan, neo luing (uaireannan muc-mhara). Nuair a tha iad lìonmhor air bàta, thèid am bàta nas slaodaiche.

Moʻylovoyoqlilar (Cirri pedia) -qisqichbaqasimonlar sinfiga mansub turkum (boshqa sistema boʻyicha kenja sinf). Suv ostidagi turli narsalar, koʻpincha harakatlanuvchi hayvonlar tanasiga yopishib yashaydi. Yumshoq tanasi alohida yaproqlardan iborat chigʻanoqb-n qoplangan. Bunday "uycha" ichidagi M. qorin qismi tepaga qaragan boʻladi. Moʻylovga oʻxshash koʻkrak oyoqlar uychaning ochiladigan "tomcha"sidan chiqarilib, yelpigʻich singari yoyiladi. M. moʻylovoyoqlari yordamida suvdan mayda filtratlarni tutib oziqdanadi. Ayrim turlari (mas, sakkulina) tekinxoʻr boʻlib, oʻnoyokli qisqichbaqasimonlar tanasida parazitlik qiladi. Oʻrtoq hayot kechirish taʼsirida M.ning koʻp organlari (koʻzlari, antennalari, bosh va qorin boʻlimlari) oʻzgargan yoki reduksiyaga uchragan. Koʻpchilik M. germafrodit. 1000 dan ortiqturi maʼlum. Dengizlarda har xil chuqurlikda hayot kechiradi. M.dan dengiz yongʻoqchalari (balanuslar) va dengiz oʻrdakchalari (Lepas) deyarli barcha dengizlarda uchraydi. Dengiz yongʻoqchalari kemalarning suv ostki qismlariga yopishib olib, yil sayin koʻpayib borishi tufayli kema ogʻirligini oshirib, uning tezligining pasayishiga sabab boʻladi. [1]

Moʻylovoyoqlilar (Cirri pedia) -qisqichbaqasimonlar sinfiga mansub turkum (boshqa sistema boʻyicha kenja sinf). Suv ostidagi turli narsalar, koʻpincha harakatlanuvchi hayvonlar tanasiga yopishib yashaydi. Yumshoq tanasi alohida yaproqlardan iborat chigʻanoqb-n qoplangan. Bunday "uycha" ichidagi M. qorin qismi tepaga qaragan boʻladi. Moʻylovga oʻxshash koʻkrak oyoqlar uychaning ochiladigan "tomcha"sidan chiqarilib, yelpigʻich singari yoyiladi. M. moʻylovoyoqlari yordamida suvdan mayda filtratlarni tutib oziqdanadi. Ayrim turlari (mas, sakkulina) tekinxoʻr boʻlib, oʻnoyokli qisqichbaqasimonlar tanasida parazitlik qiladi. Oʻrtoq hayot kechirish taʼsirida M.ning koʻp organlari (koʻzlari, antennalari, bosh va qorin boʻlimlari) oʻzgargan yoki reduksiyaga uchragan. Koʻpchilik M. germafrodit. 1000 dan ortiqturi maʼlum. Dengizlarda har xil chuqurlikda hayot kechiradi. M.dan dengiz yongʻoqchalari (balanuslar) va dengiz oʻrdakchalari (Lepas) deyarli barcha dengizlarda uchraydi. Dengiz yongʻoqchalari kemalarning suv ostki qismlariga yopishib olib, yil sayin koʻpayib borishi tufayli kema ogʻirligini oshirib, uning tezligining pasayishiga sabab boʻladi.

Rur (a wee furm o rooder) is a Shetland wird for a craitur o the infraclass Cirripedia kent fae bidin upo clumpers like lempits. Whiles rur can e'en be uised whan meanin lempit.

Ither furms o the wird includes rooder, röeder, ruder, rooddir, rhur, an rør,

Ang mga taliptip ay uri ng matitigas na mga hayop sa dagat na may kabibe[1] o krustaseanong pangkaraniwang kumakabit sa nakalubog na mga bagay, katulad ng ilalim ng mga barko, mga poste, at mga batong nasa ilalim ng dagat.[2] Mga artropoda ang mga ito na kabilang sa inpraklaseng Cirripedia na nasa loob ng subpilum na Crustacea, kaya't kamag-anakan sila ng mga alimango, alimasag, at mga ulang.

![]() Ang lathalaing ito na tungkol sa Hayop ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang lathalaing ito na tungkol sa Hayop ay isang usbong. Makatutulong ka sa Wikipedia sa nito.

Ang mga taliptip ay uri ng matitigas na mga hayop sa dagat na may kabibe o krustaseanong pangkaraniwang kumakabit sa nakalubog na mga bagay, katulad ng ilalim ng mga barko, mga poste, at mga batong nasa ilalim ng dagat. Mga artropoda ang mga ito na kabilang sa inpraklaseng Cirripedia na nasa loob ng subpilum na Crustacea, kaya't kamag-anakan sila ng mga alimango, alimasag, at mga ulang.

Teritip ya iku artropoda anggota infrakelas (biologi) Cirripedia, subfilum Crustacea, esih duwé gayutan karokepiting lan urang. Kéwan iki namung bisa tinemu ning banyu laut lan luwih seneng ning banyu cethek utawa pasang kang ombaké kuat. Carané golet panganan ya iku nyaring plankton lan kéwan iki nempel ning objek liya. Tahap larvané ana loro.

Nganti saiki kecathet ana 1.220 spésies teritip[1]. "Cirripedia" ya iku jeneng latin, kang artiné "sikilé nekuk".

Teritip ya iku artropoda anggota infrakelas (biologi) Cirripedia, subfilum Crustacea, esih duwé gayutan karokepiting lan urang. Kéwan iki namung bisa tinemu ning banyu laut lan luwih seneng ning banyu cethek utawa pasang kang ombaké kuat. Carané golet panganan ya iku nyaring plankton lan kéwan iki nempel ning objek liya. Tahap larvané ana loro.

Nganti saiki kecathet ana 1.220 spésies teritip. "Cirripedia" ya iku jeneng latin, kang artiné "sikilé nekuk".

சுருள்காலி அல்லது கொட்டலசு (Barnacle) என்பது கணுக்காலி வகையைச் சார்ந்த ஓட்டுடலிகளில் ஒன்றாகும். இது நண்டு மற்றும் இறால் ஆகிய இனங்களுடன் நெருங்கிய தொடர்புடையவையாக உள்ளன.[1]

கொட்டலசுகள், கடலில், பாறையிடுக்குகள், வாராவதித் தூண்கள், கற்கள், படகுகள், மற்றும் கப்பல்கள் போன்ற இடங்களில் ஒட்டிய நிலையில் தொகுப்புகளாக வாழ்பவையாகும்.[2]

சுருள்காலி அல்லது கொட்டலசு (Barnacle) என்பது கணுக்காலி வகையைச் சார்ந்த ஓட்டுடலிகளில் ஒன்றாகும். இது நண்டு மற்றும் இறால் ஆகிய இனங்களுடன் நெருங்கிய தொடர்புடையவையாக உள்ளன.

Barnacles are a type of arthropod constituting the subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and are hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in erosive settings. They are sessile (nonmobile) and most are suspension feeders, but those in infraclass Rhizocephala are highly specialized parasites on crustaceans. They have four nektonic (active swimming) larval stages. Around 1,000 barnacle species are currently known.[1] The name Cirripedia is Latin, meaning "curl-footed".[2] The study of barnacles is called cirripedology.

Barnacles are encrusters, attaching themselves temporarily to a hard substrate or a symbiont such as a whale (whale barnacles), a sea snake (Platylepas ophiophila), or another crustacean, like a crab or a lobster (Rhizocephala). The most common among them, "acorn barnacles" (Sessilia), are sessile where they grow their shells directly onto the substrate.[3] Pedunculate barnacles (goose barnacles and others) attach themselves by means of a stalk.[3]

Free-living barnacles are attached to the substratum by cement glands that form the base of the first pair of antennae; in effect, the animal is fixed upside down by means of its forehead. In some barnacles, the cement glands are fixed to a long, muscular stalk, but in most they are part of a flat membrane or calcified plate. These glands secrete a type of natural quick cement able to withstand a pulling strength of 5,000 pounds-force per square inch (30,000 kilopascals; 400 kilograms-force per square centimetre) and a sticking strength of 22–60 pounds-force per square inch (200–400 kilopascals; 2–4 kilograms-force per square centimetre).[4] A ring of plates surrounds the body, homologous with the carapace of other crustaceans. These consist of the rostrum, two lateral plates, two carinolaterals, and a carina.[5] In sessile barnacles, the apex of the ring of plates is covered by an operculum, which may be recessed into the carapace. The plates are held together by various means, depending on species, in some cases being solidly fused.

Inside the carapace, the animal lies on its stomach, projecting its limbs downwards. Segmentation is usually indistinct, and the body is more or less evenly divided between the head and thorax, with little, if any, abdomen. Adult barnacles have few appendages on their heads, with only a single, vestigial pair of antennae, attached to the cement gland. The eight pairs of thoracic limbs are referred to as "cirri" which are feathery and very long. The cirri extend to filter food, such as plankton, from the water and move it towards the mouth.[4]

Barnacles have no true heart, although a sinus close to the esophagus performs a similar function, with blood being pumped through it by a series of muscles.[6] The blood vascular system is minimal. Similarly, they have no gills, absorbing oxygen from the water through their limbs and the inner membrane of their carapaces. The excretory organs of barnacles are maxillary glands.

The main sense of barnacles appears to be touch, with the hairs on the limbs being especially sensitive. The adult also has three photoreceptors (ocelli), one median and two lateral. These photoreceptors record the stimulus for the barnacle shadow reflex, where a sudden decrease in light causes cessation of the fishing rhythm and closing of the opercular plates.[7] The photoreceptors are likely only capable of sensing the difference between light and dark.[8] This eye is derived from the primary naupliar eye.[9]

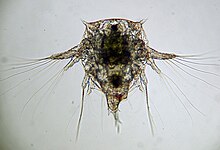

Barnacles have two distinct larval stages, the nauplius and the cyprid, before developing into a mature adult.

A fertilised egg hatches into a nauplius: a one-eyed larva comprising a head and a telson, without a thorax or abdomen. This undergoes six moults, passing through five instars, before transforming into the cyprid stage. Nauplii are typically initially brooded by the parent, and released after the first moult as larvae that swim freely using setae.[11][12]

The cyprid larva is the last larval stage before adulthood. It is not a feeding stage; its role is to find a suitable place to settle, since the adults are sessile.[11] The cyprid stage lasts from days to weeks. It explores potential surfaces with modified antennules; once it has found a potentially suitable spot, it attaches head-first using its antennules and a secreted glycoproteinous substance. Larvae assess surfaces based upon their surface texture, chemistry, relative wettability, color, and the presence or absence and composition of a surface biofilm; swarming species are also more likely to attach near other barnacles.[13] As the larva exhausts its finite energy reserves, it becomes less selective in the sites it selects. It cements itself permanently to the substrate with another proteinaceous compound, and then undergoes metamorphosis into a juvenile barnacle.[13]

Typical acorn barnacles develop six hard calcareous plates to surround and protect their bodies. For the rest of their lives, they are cemented to the substrate, using their feathery legs (cirri) to capture plankton.

Once metamorphosis is over and they have reached their adult form, barnacles continue to grow by adding new material to their heavily calcified plates. These plates are not moulted; however, like all ecdysozoans, the barnacle itself will still moult its cuticle.[14]

Most barnacles are hermaphroditic, although a few species are gonochoric or androdioecious. The ovaries are located in the base or stalk, and may extend into the mantle, while the testes are towards the back of the head, often extending into the thorax. Typically, recently moulted hermaphroditic individuals are receptive as females. Self-fertilization, although theoretically possible, has been experimentally shown to be rare in barnacles.[15][16]

The sessile lifestyle of barnacles makes sexual reproduction difficult, as the organisms cannot leave their shells to mate. To facilitate genetic transfer between isolated individuals, barnacles have extraordinarily long penises. Barnacles probably have the largest penis to body size ratio of the animal kingdom,[15] up to eight times their body length.[17]

Barnacles can also reproduce through a method called spermcasting, in which the male barnacle releases his sperm into the water and females pick it up and fertilise their eggs.[18][19]

The Rhizocephala superorder used to be considered hermaphroditic, but it turned out that its males inject themselves into the female's body, degrading to the condition of nothing more than sperm-producing cells.[20]

Most barnacles are suspension feeders; they dwell continually in their shells, which are usually constructed of six plates,[3] and reach into the water column with modified legs. These feathery appendages beat rhythmically to draw plankton and detritus into the shell for consumption.[21]

Other members of the class have quite a different mode of life. For example, members of the superorder Rhizocephala, including the genus Sacculina, are parasitic and live within crabs.[22]

Although they have been found at water depths to 600 m (2,000 ft),[3] most barnacles inhabit shallow waters, with 75% of species living in water depths less than 100 m (300 ft),[3] and 25% inhabiting the intertidal zone.[3] Within the intertidal zone, different species of barnacles live in very tightly constrained locations, allowing the exact height of an assemblage above or below sea level to be precisely determined.[3]

Since the intertidal zone periodically desiccates, barnacles are well adapted against water loss. Their calcite shells are impermeable, and they possess two plates which they can slide across their apertures when not feeding. These plates also protect against predation.[23]

Barnacles are displaced by limpets and mussels, which compete for space. They also have numerous predators.[3] They employ two strategies to overwhelm their competitors: "swamping" and fast growth. In the swamping strategy, vast numbers of barnacles settle in the same place at once, covering a large patch of substrate, allowing at least some to survive in the balance of probabilities.[3] Fast growth allows the suspension feeders to access higher levels of the water column than their competitors, and to be large enough to resist displacement; species employing this response, such as the aptly named Megabalanus, can reach 7 cm (3 in) in length;[3] other species may grow larger still (Austromegabalanus psittacus).

Competitors may include other barnacles, and disputed evidence indicates balanoid barnacles competitively displaced chthalamoid barnacles. Balanoids gained their advantage over the chthalamoids in the Oligocene, when they evolved tubular skeletons, which provide better anchorage to the substrate, and allow them to grow faster, undercutting, crushing, and smothering chthalamoids.[24]

Among the most common predators on barnacles are whelks. They are able to grind through the calcareous exoskeletons of barnacles and feed on the softer inside parts. Mussels also prey on barnacle larvae.[25] Another predator on barnacles is the starfish species Pisaster ochraceus.[26][27]

Barnacles and limpets compete for space in the intertidal zone

Underside of large Chesaconcavus sp. (Miocene) showing internal plates in bioimmured smaller barnacles

The anatomy of parasitic barnacles is generally simpler than that of their free-living relatives. They have no carapace or limbs, having only unsegmented sac-like bodies. Such barnacles feed by extending thread-like rhizomes of living cells into their hosts' bodies from their points of attachment.[8]

Barnacles were originally classified by Linnaeus and Cuvier as Mollusca, but in 1830 John Vaughan Thompson published observations showing the metamorphosis of the nauplius and cypris larvae into adult barnacles, and noted how these larvae were similar to those of crustaceans. In 1834 Hermann Burmeister published further information, reinterpreting these findings. The effect was to move barnacles from the phylum of Mollusca to Articulata, showing naturalists that detailed study was needed to reevaluate their taxonomy.[28]

Charles Darwin took up this challenge in 1846, and developed his initial interest into a major study published as a series of monographs in 1851 and 1854.[28] Darwin undertook this study, at the suggestion of his friend Joseph Dalton Hooker, to thoroughly understand at least one species before making the generalisations needed for his theory of evolution by natural selection.[29]

Some authorities regard the Cirripedia as a full class or subclass, and the orders listed above are sometimes treated as superorders. In 2001, Martin and Davis placed Cirripedia as an infraclass of Thecostraca and divided it into six orders:[30]

In 2021, Chan et al. elevated Cirripedia to subclass of the class Thecostraca, and the superorders Acrothoracica, Rhizocephala, and Thoracica to infraclass. The updated classification, which now includes 11 orders, has been accepted in the World Register of Marine Species.[31][32]

The oldest definitive fossil barnacle is Praelepas from the mid-Carboniferous, around 330-320 million years ago.[33] Older claimed barnacles such as Priscansermarinus from the Middle Cambrian (on the order of 510 to 500 million years ago)[34] do not show clear barnacle morphological traits, though Rhamphoverritor from the Silurian Coalbrookdale Formation of England may represent a stem-group barnacle.[33] Barnacles first radiated and became diverse during the Late Cretaceous. Barnacles underwent a second, much larger radiation beginning during the Neogene (last 23 million years), which continues to present.[33] In part, their poor skeletal preservation is due to their restriction to high-energy environments, which tend to be erosional – therefore it is more common for their shells to be ground up by wave action than for them to reach a depositional setting.

Barnacles can play an important role in estimating paleo-water depths. The degree of disarticulation of fossils suggests the distance they have been transported, and since many species have narrow ranges of water depths, it can be assumed that the animals lived in shallow water and broke up as they were washed down-slope. The completeness of fossils, and nature of damage, can thus be used to constrain the tectonic history of regions.[3]

Balanus improvisus, one of the many barnacle taxa described by Charles Darwin

Miocene (Messinian) Megabalanus, smothered by sand and fossilised

Barnacles are of economic consequence, as they often attach themselves to synthetic structures, sometimes to the structure's detriment. Particularly in the case of ships, they are classified as fouling organisms.[35] The number and size of barnacles that cover ships can impair their efficiency by causing hydrodynamic drag. This is not a problem for boats on inland waterways, as barnacles are exclusively marine. The stable isotope signals in the layers of barnacle shells can potentially be used as a forensic tracking method[36] for whales, loggerhead turtles[37] and marine debris, such as shipwrecks or a flaperon suspected to be from Malaysia Airlines Flight 370.[38][39][40]

The flesh of some barnacles is routinely consumed by humans, including Japanese goose barnacles (e.g. Capitulum mitella), and goose barnacles (e.g. Pollicipes pollicipes), a delicacy in Spain and Portugal.[41] The resemblance of this barnacle's fleshy stalk to a goose's neck gave rise, in ancient times, to the notion that geese literally grew from the barnacle. Indeed, the word "barnacle" originally referred to a species of goose, the barnacle goose Branta leucopsis, whose eggs and young were rarely seen by humans because it breeds in the remote Arctic.[42]

Additionally, the picoroco barnacle is used in Chilean cuisine and is one of the ingredients in curanto seafood stew.

MIT researchers developed an adhesive, inspired by a protein-based bioglue produced by barnacles to firmly attach to rocks, which can form a tight seal to halt bleeding within about 15 seconds of application.[43]

Barnacles attached to pilings along the Siuslaw River in Oregon

Goose barnacles in a restaurant in Madrid

Barnacles are a type of arthropod constituting the subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and are hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in erosive settings. They are sessile (nonmobile) and most are suspension feeders, but those in infraclass Rhizocephala are highly specialized parasites on crustaceans. They have four nektonic (active swimming) larval stages. Around 1,000 barnacle species are currently known. The name Cirripedia is Latin, meaning "curl-footed". The study of barnacles is called cirripedology.

Ia tipo de artropodoj konstituas la infraklason Cirripedia en la subfilumo Krustacoj, kiuj estas iel rilataj al kraboj kaj omaroj. Ciripieduloj estas nur maraj, kaj tendencas vivi en neprofundaj kaj tajdaj akvoj, tipe en eroziaj ejoj. Ili estas sesilaj (nonmotile) pendomanĝantoj, kaj havas du nektonajn (aktive naĝantaj) larvajn stadiojn. Nune oni konas ĉirkaŭ 1,220 ciripiedajn speciojn.[1] La nomo "Cirripedia" estas latina, signife "buklopieda".

Ekzemple: balano (Balanus)

Ia tipo de artropodoj konstituas la infraklason Cirripedia en la subfilumo Krustacoj, kiuj estas iel rilataj al kraboj kaj omaroj. Ciripieduloj estas nur maraj, kaj tendencas vivi en neprofundaj kaj tajdaj akvoj, tipe en eroziaj ejoj. Ili estas sesilaj (nonmotile) pendomanĝantoj, kaj havas du nektonajn (aktive naĝantaj) larvajn stadiojn. Nune oni konas ĉirkaŭ 1,220 ciripiedajn speciojn. La nomo "Cirripedia" estas latina, signife "buklopieda".

Ekzemple: balano (Balanus)

Los cirrípedos (Cirripedia) son una subclase de crustáceos maxilópodos denominados comúnmente percebes, incluyendo la bellota de mar y la anatifa. Son uno de los grupos de crustáceos más modificado; su peculiar morfología hizo que hace dos siglos se confundieran con moluscos. De hecho, muchos de los nombres que se le dan a diferentes partes de su cuerpo responden a esta antigua creencia (manto y placas por ejemplo). Sin embargo, al estudiar sus larvas se vio que eran similares a las de ostrácodos, lo que fue clave para estudios posteriores que concluyeron que se trataba de crustáceos con una morfología "aberrante". Entre los cirrípedos encontramos algunas especies de interés comercial como el percebe (Pollicipes cornucopia) y el picoroco (Austromegabalanus psittacus).

Los cirrípedos tienen dos tipos corporales básicos: con y sin pedúnculo. Los que no tienen pedúnculo cubren normalmente todo el litoral rocoso, mientras que los pedunculados prefieren vivir mar adentro o sobre objetos flotantes. Además de estos dos tipos básicos, existe un tercer tipo de morfología algo diferente, los llamados "amorfos" o Verrucomorfa. Estos últimos no son simétricos y viven en aguas profundas, generalmente sobre las espinas de erizos (ver Echinoidea) o como comensales de ballenas.

Los cirrípedos poseen dos estados larvarios: el primero, de larva nauplius, y el segundo, de larva cipris o cíprida:

Cuando una larva cipris encuentra un lugar adecuado para fijarse, lo hace e inicia el proceso de metamorfosis, dando lugar a un cirrípedo juvenil, que, típicamente, posee una morfología a desarrollar consistente en seis placas a modo de armadura, externas. Durante el resto de sus vidas, los cirrípedos son sésiles y se alimentan filtrando plancton con sus apéndices y liberando sus gametos. Se les suele encontrar en la zona intermareal.

Una vez completada la metamorfosis y alcanzada la forma adulta, siguen creciendo, pero no sufren mudas o ecdisis; por el contrario, crecen por adición de material a su cubierta calcificada.

Como muchos otros invertebrados, los cirrípedos son hermafroditas y alternan el estado masculino y femenino temporalmente: es decir, existe un estado unisexual alterno o, lo que es lo mismo, un individuo puede ser inicialmente macho y luego hembra, y viceversa. En cuanto a la morfología del órgano reproductor, los percebes ostentan el récord de tamaño de pene, en relación a su cuerpo, de todo el reino animal.[1]

Existen cirrípedos de biología muy distinta: es el caso de los representantes del género Sacculina, que son parásitos de cangrejos.

Corrosión causada, en parte, por cirrípedos.

Algunos percebes son consumidos como marisco, fundamentalmente en Grecia, España y otros países mediterráneos.

Se explota sobre todo en Galicia (Pollicipes pollicipes), constituyendo un producto típico de su gastronomía; acostumbra a ser recogido manualmente con riesgo considerable para los operarios, localmente llamados percebeiros.

Sus parientes americanos comestibles son el gooseneck barnacle (Pollicipes polymerus), en el Pacífico boreal, y el picoroco (Megabalanus psittacus), en el Pacífico austral.

Estos organismos pueden unirse a casi cualquier especie marina; además de ballenas y otros cetáceos también pueden fijarse en tortugas marinas, cangrejos, langostas, moluscos bivalvos, algunos peces e incluso se han visto en delfines y manatíes, y muchas otras criaturas oceánicas

Los cirrípedos pueden unirse a estructuras navales y no sólo a sustratos naturales. Es el caso de los cascos de los buques, cuya consecuencia es denominada incrustación. Este hecho es evitado en las industrias navieras por adición de pinturas anti-incrustación, que alteran la biología de la especie interfiriendo en el desarrollo y cambio de sexo de los individuos.

En Europa, hasta bien entrada la Edad Moderna se creyó que las aves llamadas barnaclas eran la metamorfosis madura de los percebes (llamados en inglés barnacles). La gente burlaba así el ayuno de carnes durante la cuaresma (pues de acuerdo con la doctrina cristiana durante ese periodo las únicas carnes que se podían comer eran las de pescados y mariscos), y lo hacía comiendo las aves llamadas barnaclas y otras similares (gansos y patos), que eran clasificadas como "moluscos" o "crustáceos". Uno de los argumentos para tan curiosa taxonomía era el hecho de que los percebes tienen órganos que recuerdan a plumas.

Seguimos el esquema propuesto por Martin y Davis que sitúa a los Cirripedia como infraclase de los Thecostraca y la consiguiente clasificación hasta el nivel de orden.[2]

Infraclase Cirripedia Burmeister, 1834

Los cirrípedos (Cirripedia) son una subclase de crustáceos maxilópodos denominados comúnmente percebes, incluyendo la bellota de mar y la anatifa. Son uno de los grupos de crustáceos más modificado; su peculiar morfología hizo que hace dos siglos se confundieran con moluscos. De hecho, muchos de los nombres que se le dan a diferentes partes de su cuerpo responden a esta antigua creencia (manto y placas por ejemplo). Sin embargo, al estudiar sus larvas se vio que eran similares a las de ostrácodos, lo que fue clave para estudios posteriores que concluyeron que se trataba de crustáceos con una morfología "aberrante". Entre los cirrípedos encontramos algunas especies de interés comercial como el percebe (Pollicipes cornucopia) y el picoroco (Austromegabalanus psittacus).

Los cirrípedos tienen dos tipos corporales básicos: con y sin pedúnculo. Los que no tienen pedúnculo cubren normalmente todo el litoral rocoso, mientras que los pedunculados prefieren vivir mar adentro o sobre objetos flotantes. Además de estos dos tipos básicos, existe un tercer tipo de morfología algo diferente, los llamados "amorfos" o Verrucomorfa. Estos últimos no son simétricos y viven en aguas profundas, generalmente sobre las espinas de erizos (ver Echinoidea) o como comensales de ballenas.

Vääneljalalised ehk vääneljalgsed (Cirripedia) on vähkide hõimkonda (või alamhõimkonda) kuuluv üksnes mereloomade klass. Uuemais süstemaatikais paigutatakse nad aerjalgsete (Maxillopoda) klassi, andes neile siis alamklassi staatuse.

"Loomade elu" arvab nad lülijalgsete hõimkonda lõpuslülijalgsete alamhõimkonda vähkide ehk koorikloomade klassi aerjalgsete alamklassi.[1]

Eesti rannikuvetes elab üks selle taksoni esindaja: riimvettki taluv harilik tõruvähk (Balanus improvisus). Troopilistes ja subtroopilistes meredes on ühed tavalisimad nuivähi (Lepas) perekonna esindajad.

Väliselt ei meenuta vääneljalalised üldse vähke. Täiskasvanud isendid on kinnitunud kõikmõeldavate veealuste esemete külge. Vääneljalalise keha ümbritseb tugev lubikoda. See koosneb plaatidest, millest osa on omavahel liikuvalt ühendatud. Vähk saab neid laiali ajada ja tekkinud pilust välja sirutada rindmikujalgu, millega toitu haarab.[2]

Tugev lubikoda ja kinnistunud eluviis tekitasid pikka aega segadust vääneljalaliste süstemaatilise kuuluvuse määramisel. Cuvier paigutas nad limuste hulka. Lamarck käsitles neid üleminekurühmana usside ja limuste vahel. Nende kuuluvus vähkide hulka tõestati alles 1830. aastail, kui õpiti tundma vääneljalaliste vastseid, kes sarnanevad teiste vähkide vastsetega. [2]

Vääneljalalised ehk vääneljalgsed (Cirripedia) on vähkide hõimkonda (või alamhõimkonda) kuuluv üksnes mereloomade klass. Uuemais süstemaatikais paigutatakse nad aerjalgsete (Maxillopoda) klassi, andes neile siis alamklassi staatuse.

"Loomade elu" arvab nad lülijalgsete hõimkonda lõpuslülijalgsete alamhõimkonda vähkide ehk koorikloomade klassi aerjalgsete alamklassi.

Eesti rannikuvetes elab üks selle taksoni esindaja: riimvettki taluv harilik tõruvähk (Balanus improvisus). Troopilistes ja subtroopilistes meredes on ühed tavalisimad nuivähi (Lepas) perekonna esindajad.

Väliselt ei meenuta vääneljalalised üldse vähke. Täiskasvanud isendid on kinnitunud kõikmõeldavate veealuste esemete külge. Vääneljalalise keha ümbritseb tugev lubikoda. See koosneb plaatidest, millest osa on omavahel liikuvalt ühendatud. Vähk saab neid laiali ajada ja tekkinud pilust välja sirutada rindmikujalgu, millega toitu haarab.

Tugev lubikoda ja kinnistunud eluviis tekitasid pikka aega segadust vääneljalaliste süstemaatilise kuuluvuse määramisel. Cuvier paigutas nad limuste hulka. Lamarck käsitles neid üleminekurühmana usside ja limuste vahel. Nende kuuluvus vähkide hulka tõestati alles 1830. aastail, kui õpiti tundma vääneljalaliste vastseid, kes sarnanevad teiste vähkide vastsetega.

Siimajalkaiset (Cirripedia) ovat meressä eläviä äyriäisiä joista suurin osa viettää aikuiselämänsä alustaan kiinnittyneinä. Heimoja ovat muun muassa hanhenkaulat (Lepadidae), joilla on varsi, ja varrettomat merirokot (Balanidae). Tällä hetkellä tunnetaan noin 1 220 siimajalkaislajia. Nimi "Cirripedia" tulee latinasta ja tarkoittaa "kiharajalkaista". Useita erityisesti veneiden pohjiin kiinnittyviä siimajalkaisia kutsutaan usein merirokoiksi, vaikka ne eivät olisi merirokkojen heimoa.

Ensimmäisenä siimajalkaisia kattavasti tutki ja luokitteli Charles Darwin, joka julkaisi sarjan niitä käsitteleviä monografioita vuosina 1851–1854. Darwin aloitti tutkimuksensa ystävänsä Joseph Dalton Hookerin ehdotuksesta.

Siimajalkaisilla on kaksi toukkavaihetta. Ensimmäinen on nauplius-vaihe, joka viettää aikansa osana eläinplanktonia, kelluen vedessä kulkien virtojen mukana, syöden ja luoden kuortansa. Tämä vaihe kestää noin kaksi viikkoa (viisi toukkavaiheen kuorenluontia), kunnes naupliustoukka muuttaa muotoaan uivaksi kypristoukaksi ja lopettaa syömisen. Toukka asettuu paikoilleen löydettyään paikan joka vaikuttaa turvalliselta ja hedelmälliseltä. Kun sopiva paikka löytyy, toukka liimaantuu pää edellä alustaan ja muuttuu aikuiseksi. Tyypillisesti se kasvattaa neljä, kuusi tai kahdeksan kovaa panssarilevyä suojaksi ympärilleen. Siimajalkainen viettää loppuelämänsä alustaansa liimaantuneena, käyttäen höyhenmäisiä siimajalkojaan planktonin pyydystämiseen. Siimajalkaisia esiintyy yleensä rannoilla alueilla, jotka paljastuvat laskuveden aikaan.

Aikuinen siimajalkainen jatkaa kasvuaan, mutta ei enää luo kuortaan. Sen sijaan se kasvattaa panssarikuortaan lisäämällä uutta ainetta kuorilevyihin.

Joillain luokan lajeilla on yllä selostetusta täysin poikkeavat elämäntavat. Esimerkiksi Sacculina-suvun eliöt ovat taskuravuissa asuvia ulkoloisia.

Kuten monet selkärangattomat, siimajalkaiset ovat kaksineuvoisia joilla on sekä koiras- että naarasroolit. Siimajalkaiset hedelmöittävät toisensa (tai itsensä) peniksellä; siimajalkaisen penis on koko eläinkunnan pisin ruumiin kokoon suhteutettuna [1].

Siimajalkaiset kiinnittyvät usein ihmisten tekemiin rakenteisiin kuten veneisiin ja laitureihin aiheuttaen joskus vaurioita. Erityisesti laivoille siimajalkaiset ovat haitallisia, sillä pohjaan kiinnittyneinä ne kasvattavat veden vastusta ja siten polttoaineen kulutusta. Joitakin lajeja, ainakin Mitella pollicipes ja Pollicipes cornucopia, käytetään ihmisruoaksi etenkin Ranskassa ja Espanjassa.[2] [3]

Ainoa Suomen rannikolla elävä siimajalkainen on Itämereen 1840-luvulla tulokaslajina saapunut merirokko (Amphibalanus improvisus). Merirokko on alun perin amerikkalainen tai australialainen laji, joka on laivojen rungoilla levinnyt ympäri maailmaa. Muualla se viihtyy erityisesti vähäsuolaisissa jokisuissa.

Valkoposkihanhien englanninkielinen nimi barnacle goose tulee vanhasta eurooppalaisesta uskomuksesta, että hanhet syntyvät hanhenkauloista (Pollicipes polymerus). Hanhien untuvikkoja ei koskaan nähty, sillä hanhet pesivät kaukana Jäämeren rannikkoseuduilla. Koska hanhenkaulat ovat mereneläviä, laskettiin myös hanhet kaloiksi, joita voitiin syödä perjantaisin katolisen paaston alkaessa

Siimajalkaiset (Cirripedia) ovat meressä eläviä äyriäisiä joista suurin osa viettää aikuiselämänsä alustaan kiinnittyneinä. Heimoja ovat muun muassa hanhenkaulat (Lepadidae), joilla on varsi, ja varrettomat merirokot (Balanidae). Tällä hetkellä tunnetaan noin 1 220 siimajalkaislajia. Nimi "Cirripedia" tulee latinasta ja tarkoittaa "kiharajalkaista". Useita erityisesti veneiden pohjiin kiinnittyviä siimajalkaisia kutsutaan usein merirokoiksi, vaikka ne eivät olisi merirokkojen heimoa.

Ensimmäisenä siimajalkaisia kattavasti tutki ja luokitteli Charles Darwin, joka julkaisi sarjan niitä käsitteleviä monografioita vuosina 1851–1854. Darwin aloitti tutkimuksensa ystävänsä Joseph Dalton Hookerin ehdotuksesta.

Les Cirripèdes (initialement orthographié Cirrhipèdes), ou Cirripedia, sont une infra-classe d’animaux, tous exclusivement marins, appartenant au sous-embranchement des Crustacés. Ils partagent donc un certain nombre de caractères fondamentaux avec des organismes comme le Homard, le Crabe ou le Cloporte, dont ils sont en apparence très différents sur le plan morphologique.

Les Cirripedia sont des Crustacés, comme le prouvent leurs stades larvaires. Ils comprennent notamment les Lépadomorphes (anatifes), les Balanomorphes (comme les balanes), et les parasites Rhizocéphales (comme la Sacculine, Sacculina carcini, parasite du Crabe vert Carcinus maenas), dont le corps est profondément modifié et ne peuvent être reconnus comme Cirripèdes que par l’anatomie de leurs larves. Celles-ci se fixent par les antennules sur un support quelconque, et entament une métamorphose complète qui produira les morphologies adultes très particulières de ce groupe[1]. Les animaux ainsi fixés ne se déplaceront plus jamais[2]. Quand ils ne sont pas parasites, les adultes peuvent être pédonculés ou operculés, et sessiles. Les Cirripèdes sont munis de fouets garnis de soies (les « cirres ») destinés à capter des particules organiques en suspension dans l’eau.

Les Cirripèdes sont tous fixés aux rochers, à des objets flottants divers, à des organismes vivants (tortues, mammifères marins) ou enfoncés dans des coquilles de mollusques ou dans le squelette d’un coralliaire.

Les formes libres (non parasites)[3] les plus simples (ordre Pedunculata) sont fixées par l’intermédiaire d’un long pédoncule cylindrique, logeant principalement l’ovaire, au sommet duquel se trouve le corps de l’animal, protégé par un ensemble de plaques et constituant le capitulum, aplati, symétrique, et ouvert sur l’extérieur par un long orifice susceptible d’être fermé.

Le pédoncule disparaît dans l’ordre des Sessilia, qui sont fixés directement sur le support, par exemple les balanes, très communes sur les rochers de l’estran.

Dans le corps des Cirripèdes libres on reconnaît deux parties (= tagmes) principales, décrites dans les sous-chapitre suivants.

Le céphalon est constitué des 5 métamères typiques des Crustacés, pourvus d’appendices, au moins chez les larves. Les antennules (A1) servent à la fixation : elles ne sont plus visibles chez les adultes. Les antennes (A2), bien développées chez les larves nauplius, disparaissent chez les adultes. Les pièces buccales, réunies en un mamelon centré sur la bouche, sont constituées par les mandibules (Md), les maxillules (Mx1) et les maxilles (Mx2).

Le thorax est constitué de 6 métamères porteurs chacun d’une paire d’appendices : les cirres. Ils comportent une base de 2 articles dont le dernier porte deux rames ; l’une interne (endopodite), l’autre externe (exopodite), d’aspect très semblable et formés de plusieurs articles garnis de soies. Les trois derniers possèdent des rames allongées sur lesquelles se trouvent des soies rigides très longes qui, en s’entrecroisant, constituent un filtre permettant la capture des particules en suspension dans l’eau de mer (phyto et zooplancton, détritus divers) dont l’animal se nourrit. La capture de la nourriture[4] est, soit relativement passive, les cirres étant étalés la plus grande partie du temps pour filtrer le courant d’eau qui les traverse (fréquent chez les lepadomorphes), soit très active, les cirres accomplissant de rapides mouvements de va-et-vient afin de capturer les particules. Ces deux techniques peuvent cependant se combiner de manière variée, notamment chez les balanomorphes.

L’abdomen et le telson ont pratiquement disparu et ne sont représentés que par une aire vestigiale autour de l’anus, situé à l’arrière du thorax.

Un pénis impair, extrêmement extensible, est inséré à l’arrière du thorax, en avant de l’anus.

Les Cirripèdes sont en majorité hermaphrodites. La fécondation croisée est rendue possible par leurs habitudes grégaires et l’extensibilité de leur pénis. Certaines espèces (genres Ibla et Scalpellum) possèdent en outre des mâles nains (« mâles complémentaires » de Darwin) qui vivent attachés dans la cavité palléale des individus normaux, hermaphrodites, ou parfois seulement femelles[3].

Les œufs sont incubés dans la cavité palléale de l’adulte et éclosent en libérant une larve nauplie caractérisée notamment par la possession de cornes frontales de chaque côté de la carapace. La phase nauplius comporte 4 à 6 stades ; elle est suivie de la phase cypris, qui n’en comporte qu’un seul.

C’est Lamarck qui a reconnu l’originalité et l’unité de ce groupe dont il a forgé le nom à partir du latin cirrus (« boucle de cheveux ») et ped- (« pied »), faisant par là allusion à la forme de leurs appendices thoraciques semblables à des filaments recourbés. Mais Lamarck écrit, dans « Philosophie zoologique »[5], que les Cirripèdes « ne peuvent être des Crustacés ». Il leur voit des affinités avec les annélides et les mollusques (dans lesquels Cuvier les classe). C’est Thompson [3] qui, en 1830, à la suite de l’observation de la métamorphose d’une larve cypris, recueillie dans le plancton, en balane, démontre sans aucun doute possible l’appartenance de cet animal, et d’une manière générale des Cirripèdes, aux Crustacés. En fait Slabber avait dès 1767 observé la larve nauplius caractéristique des Crustacés, dans un Lepas mais n’avait pas su en tirer les conséquences.[réf. nécessaire]

C’est à Charles Darwin et à ses monographies sur les Cirripèdes (1851-1854) que nous devons ce qui constitue encore le socle de nos connaissances sur ces animaux.

À l’heure actuelle[6], les Cirripèdes sont rangés dans la classe des Maxillopodes dont ils constituent une infraclasse. Ils comprennent les quatre super-ordres des Acrothoracicanes, des Rhizocéphales, des Thoraciques et des Sessilies. Noter que l’ordre d'Apodes qui figurait dans les anciennes classifications a été retiré des Cirripèdes car son unique représentant est, en fait, le stade transitoire d’un isopode parasite[7].

La particularité des formes de certaines espèces de Cirripèdes ainsi que des observations mal interprétées ou fantaisistes ont trompé d’anciens observateurs qui ont cru voir dans ces organismes une étape dans le cycle biologique de certains oiseaux migrateurs comme les canards ou les oies bernaches. Ces oiseaux apparaissent en effet à chaque automne sans que l’on sût, à l’époque, où ni comment ils se reproduisaient. De ce mystère, ajouté au fait que l’on avait observé des branches mortes porteuses de cirripèdes tels que les anatifes, échouées sur les rivages, naquit, peut-être vers le VIIIe siècle[8], le mythe de l’« arbre à canards » rapporté par Claude Duret (1605) [9]. Ce mythe imagine un arbre qui pousse, fort opportunément, au bord des lacs ou de la mer, porte des feuilles (ou des fruits, selon les versions) qui tombent dans l’eau pour se transformer en poissons ou sur le sol pour se transformer en canards.

De cette légende proviennent les noms des anatifes (bâti sur la racine « anas » = canard) et de l’espèce Lepas anatifera (Lepas porteur de canards). Elle explique l’appellation de bernaches, nom d’une oie, donné autrefois par les marins aux balanes[10], que les Anglais nomment « barnacles » [réf. souhaitée]. De même, le nom « cravant » concernant une bernache se retrouve, déformé en « gravants », dans le langage maritime, pour designer ces mêmes balanes.

Le pouce-pied (Pollicipes pollicipes), récolté sur le littoral atlantique en France et sur la péninsule Ibérique, constitue un mets très apprécié (c’est essentiellement l’ovaire de l’animal qui est consommé). Mais l’importance économique des Cirripèdes réside surtout dans le fait que ce sont des agents de salissure (« fouling »)[11] extrêmement importants qui se fixent en masse sur les carènes des navires, dans les conduites d’eau de mer. Ils sont de ce fait responsables du ralentissement de la progression des bateaux, d’une augmentation de la consommation de carburant et de frais de carénage ainsi que de curage des canalisations extrêmement coûteux.

Trois types de Cirripèdes sont aisément identifiables,

Selon World Register of Marine Species (10 mars 2017)[12] : ...

Selon ITIS (10 mars 2017)[13] :

Lepas anatifera, un anatife

Chthamalus stellatus, une balane

Pollicipes polymerus, un pouce-pied

Sacculina carcini, une sacculine parasite sur le ventre d'un crabe.

Les cirripèdes sont représentés dans la franchise de jeux Pokémon à travers deux créatures : Binacle et Barbaracle, en français Opermine et Golgopathe[14].

Les Cirripèdes (initialement orthographié Cirrhipèdes), ou Cirripedia, sont une infra-classe d’animaux, tous exclusivement marins, appartenant au sous-embranchement des Crustacés. Ils partagent donc un certain nombre de caractères fondamentaux avec des organismes comme le Homard, le Crabe ou le Cloporte, dont ils sont en apparence très différents sur le plan morphologique.

Crústach muirí a chónaíonn lena bhun greamaithe le foshraith chrua nó orgánach eile. An cholainn imchlúdaithe i sliogán, déanta as plátaí cailcreacha. De réir cineáil, itheann sí trí bhia a scagadh as an uisce le géaga tóracsacha oiriúnaithe (cirri). Níos mó ná 1,000 speiceas, a fhaightear i ngach áit ón gcrios idirthaoide go dtí an fharraige dhomhain. Cuid acu seadánach ar phortáin.

A dos cirrípedes (Cirripedia) é unha infraclase de crustáceos mariños da clase dos maxilópodos e da subclase dos tecóstracos.[1]

Os seus membros máis coñecidos son os percebes, pero a clase inclúe outras especies como os arneiros ou o percebe da madeira.

A especie representativa é o percebe común (Pollicipes pollicipes).[2]

A infrclase foi descrita en 1834 polo naturalista, paleontólogo e zoólogo alemán nacionalizado arxentino Hermann Burmeister (tamén coñecido como Karl Hermann Konrad Burmeister ou Carlos Germán Conrado Burmeister).

O nome científico Cirripedia está formado pola unión dos elementos do latín científico cirr- e -pedia, derivados, respectivamente, do latín cirrus, "rizo", "floco", e a raíz pedi- do xenitivo de pes, pedis, "pé",[3] coa adición do sufixo -a para indicar plural.

Ademais de polo nome actualmente válido, a infrasclase coñeceuse tamén polos sinónimos seguintes:[Cómpre referencia]

Segundo o WoRMS, a clasificación taxonómica dos cirrípedos é a seguinte:

Porén, o ITIS considera esta outra: [4]

Son de hábitos sésiles (viven fixos sobre o substrato) polo que durante séculos foron considerados moluscos.

Foi ó coñecer o ciclo biolóxico e estudar a morfoloxía das larvas, tipo cipris, cando se admitiu que se trataba de crustáceos cunha estrutura moi modificada.

Poden dispoñer dun pedúnculo, co que se fixan ó substrato, ou non, pero en calquera caso teñen o corpo protexido por placas calcáreas.[Cómpre referencia]

As larvas son sempre de vida libre, e atravesan por dúas fases larvarias:

Cando a larva cipris atopa un lugar adecuado, fíxase e inicia o proceso de metamorfose, dando lugar a un cirrípedo xuvenil, que posúe unha morfoloxía consistente en seis placas externas a modo de armadura. Durante o resto das súas vidas, os cirrípedos son sésiles e aliméntanse por filtración, grazas ás correntes de auga creadas ó axitar os seus apéndices. Unha vez completada a metamorfose e alcanzada a forma adulta, seguen crecendo pero xa sen sufrir mudas, senón por adición de material á cuberta calcificada.

Como outros invertebrados, os cirrípedos son hermafroditas e alternan o estado masculino e feminino temporalmente. É dicir un mesmo individuo pode ser inicialmente macho e logo femia, ou viceversa.

Algúns cirrípedos, como as especies do xénero Sacculina, son parasitos doutros crustáceos. Outros, como os chamados "amorfos" ou Verrucomorfa son comensalistas e viven sobre as espinas dos ourizos ou sobre a pel das baleas.

Lepas anatifera, unha anatifa

Sacculina carcini, unha saculina parasita sobre o abdome dun cangrexo

Percebes nunha fenda dunha rocha da praia de Fonforrón (Porto do Son)

Venda de percebes nun mercado.

É un marisco que destaca polo seu alto prezo

Prato de percebes nun restaurante de Madrid

A dos cirrípedes (Cirripedia) é unha infraclase de crustáceos mariños da clase dos maxilópodos e da subclase dos tecóstracos.

Os seus membros máis coñecidos son os percebes, pero a clase inclúe outras especies como os arneiros ou o percebe da madeira.

A especie representativa é o percebe común (Pollicipes pollicipes).

Teritip adalah artropoda anggota infrakelas Cirripedia, subfilum Crustacea, sehingga berkerabat dengan kepiting dan udang. Hewan ini hanya ditemukan di air laut dan cenderung menyukai perairan dangkal atau pasang yang bergelombang kuat. Cara mencari makannya adalah dengan menyaring plankton dan hewan ini melekat pada suatu objek. Tahap larvanya ada dua.

Sampai saat ini tercatat 1.220 spesies teritip[1]. "Cirripedia" adalah nama dari bahasa Latin, berarti "berkaki terlipat".

Teritip adalah artropoda anggota infrakelas Cirripedia, subfilum Crustacea, sehingga berkerabat dengan kepiting dan udang. Hewan ini hanya ditemukan di air laut dan cenderung menyukai perairan dangkal atau pasang yang bergelombang kuat. Cara mencari makannya adalah dengan menyaring plankton dan hewan ini melekat pada suatu objek. Tahap larvanya ada dua.

Sampai saat ini tercatat 1.220 spesies teritip. "Cirripedia" adalah nama dari bahasa Latin, berarti "berkaki terlipat".

I cirripedi (Cirripedia Burmeister, 1834; in inglese "barnacle") sono un'infraclasse di crostacei, appartenente alla sottoclasse dei Thecostraca. Sono esclusivamente marini e comprendono circa un migliaio di specie. Le appendici del torace sono trasformate in cirri che servono per filtrare l'acqua e portare il cibo alla bocca. Possono avere vita libera, e in tal caso aderiscono ad una varietà di substrati, tra cui sporgenze rocciose, scafi e anche balene, oppure essere parassiti in genere di altri artropodi.

Fra i crostacei, i cirripedi sono quelli che più si discostano dallo schema tipico, tant'è che ancora nel XIX secolo venivano confusi con molluschi[1]; da ciò deriva la nomenclatura delle parti del corpo dei cirripedi, simile a quella usata per i molluschi. Le larve cypris sono simili agli ostracodi, con un carapace bivalve[2], il che permise di classificarli come crostacei con una morfologia aberrante.

I rizocefali hanno invece un'anatomia molto semplice, sprovvista di articolazioni o segmentazioni visibili. In comune con gli altri ordini di cirripedi hanno unicamente lo stadio larvale, dato che l'adulto vive come parassita di altri crostacei[3].

Il corpo di un cirripede non parassita è composto da due parti principali: il peduncolo (corrispondente alla testa dell'animale), con cui si fissano al substrato, e il capitolo, che è di solito ricoperto di piastre calcaree e contiene gli organi[4]. A seconda che i cirripedi si servano o meno di un peduncolo per ancorarsi ai diversi substrati, essi vengono denominati:

I balani hanno il carapace (muraglia) formato di solito da 6 o 8 piastre calcaree e un'apertura subcircolare che all'occorrenza può essere chiusa da un opercolo composto di quattro pezzi denominati terga e scuta (i Verrucomorpha hanno un solo tergo e un solo scuto)[3].

Nei cirripedi le appendici sono molto ridotte, le antenne vengono impiegate dalla larva cypris per fissarsi al substrato e sono dunque invisibili nell'adulto, in cui esistono solo sei paia di arti toracici, trasformati in cirri biforcuti e impiegati per la nutrizione per filtrazione[3][4].

I cirripedi hanno taglia abbastanza grande, di solito compresa tra 0,5 e 5 cm[3].

I cirripedi senza peduncolo ricoprono di solito ogni tipo di litorale roccioso, mentre quelli peduncolati preferiscono aree più esposte al mare o oggetti galleggianti. Esistono anche diverse specie che sono commensali su altri organismi come granchi, tartarughe marine o cetacei. Oltre a questi due tipi di cirripedi, ve ne è un terzo: sono detti "amorfi" o Verrucomorpha. Questi ultimi sono simili ai balani ma hanno carapace asimmetrico e di solito vivono in acque profonde[3][4].

Alcuni generi di Sessilia, come Chthamalus, vivono nella zona sopralitorale, quindi perennemente fuor d'acqua ed esposti solo agli spruzzi delle onde[3].

I rhizocefali si sviluppano all'interno dell'ospite, con unicamente l'apparato riproduttore che fuoriesce[4].

Spesso i cirripedi formano colonie numerosissime composte da migliaia di individui[4].

I cirripedi hanno due stadi larvali planctonici distinti:

Una volta raggiunta la forma adulta, continuano a depositare carbonato di calcio sulle piastre del carapace. Durante il resto della loro vita, i cirripedi a vita libera sono sessili e si alimentano filtrando plancton con le appendici. I cirripedi sono ermafroditi ed alternano i periodi in cui si riproducono come femmine e come maschi. L'autofecondazione è però molto rara[5]. La fecondazione è interna ed avviene attraverso un lungo pene che raggiunge gli individui vicini. Le uova vengono incubate nel carapace e vengono liberati direttamente dei naupli. La muta avviene regolarmente ma non riguarda le piastre calcaree[4].

Nei Rhizocephala il maschio è minuscolo e vive a sua volta come parassita della femmina[3].

I cirripedi producono grandi quantità di larve e le loro fasi pelagiche costituiscono stagionalmente una componente predominante dello zooplancton costiero[5].

Lo schema proposto da Martin e Davis situa l'infraclasse Cirripedia come sottoclasse di Thecostraca e con tre superordini[6]:

Infraclasse Cirripedia Burmeister, 1834

Lo studio dei fossili di Cirripedia è stato largamente approfondito da Charles Darwin[7], che ne ha classificato numerose specie, confermando che questi animali hanno una lunga storia geologica che permette di valutare le specie contemporanee. Darwin iniziò a raccogliere esemplari sudamericani, per poi spostarsi su esemplari europei, principalmente del Cretaceo. Le deduzioni da lui tratte durante i suoi 8 anni sui cirripedi, sono valide a tutt'oggi. Darwin scrisse che molti scalpellidi erano apparsi nel Giurassico, per poi diffondersi estensivamente nel Cretacico, raggiungendo il massimo durante il Triassico; la linea dell'evoluzione da una specie all'altra è identificabile così come la vicinanza fra specie e generi di cirripedi[7].

Withers ha pubblicato numerosi articoli sui fossili di cirripedi, stabilendo una base di 22000 esemplari classificati in 217 specie che ne illustra la storia tassonomica[8].

I primi reperti fossili riconducibili ai Cirripedia sono molto antichi, provenendo da Priscansermarinus del Cambriano medio (sui 500 milioni di anni fa)[9], ma non vi sono resti scheletrici fino al Neogene (l'era più recente, gli ultimi 20 milioni di anni)[10]. Tracce fossili lasciate da specie di Acrothoracica (Rogerella) sono abbastanza comuni e databili dal Devoniano ad oggi.

Nello studio dei paleo-mari, i fossili di cirripedi servono a valutarne la profondità: il grado di usura del fossile indica la distanza sulla quale è stato trasportato, suggerendo che l'animale viveva in acque poco profonde per poi rompersi quando è stato portato dalle correnti a profondità maggiori. Lo stato dei fossili e il danno subito portano quindi informazioni sulla storia tettonica della regione[10].

Altri fossili di cirripedi sono serviti da punti di riferimento per la classificazione, come l'Archaeolepas redtenbacheri (Germania), il Praelepas jaworski del Carbonifero (Russia), il Brachylepas naissanti o il Cyprilepas Holmi del Siluriano superiore (Estonia).

Megabalanus del Messiniano, limato dalla sabbia e poi fossilizzato.

Tra i cirripedi vi sono alcune specie commestibili, consumate soprattutto in Spagna e Portogallo, come Pollicipes cornucopia e Austromegabalanus psittacus. L'importanza dei cirripedi è però soprattutto relativa alle incrostazioni che producono sulla carena delle navi compromettendone le prestazioni e aumentando il consumo di carburante[4].

I cirripedi (Cirripedia Burmeister, 1834; in inglese "barnacle") sono un'infraclasse di crostacei, appartenente alla sottoclasse dei Thecostraca. Sono esclusivamente marini e comprendono circa un migliaio di specie. Le appendici del torace sono trasformate in cirri che servono per filtrare l'acqua e portare il cibo alla bocca. Possono avere vita libera, e in tal caso aderiscono ad una varietà di substrati, tra cui sporgenze rocciose, scafi e anche balene, oppure essere parassiti in genere di altri artropodi.

Ūsakojai (lot. Cirripedia) – vėžiagyvių (Crustacea) infraklasė, priklausanti žandakojams. Tai jūriniai vėžiagyviai, turintys iš kalkingų plokštelių kriauklę. Galva sunykusi, nes prisitvirtina galvos dalimi. Antenos ir burnos galūnės redukuotos. Galvos vietoj gali išaugti ilgas stiebelis arba padas. Jame esančios liaukos padeda prisitvirtinti prie substrato. Turi šeriuotas krūtinės kojas, kurios lyg ūsai tai išsitiesia, tai susisuka – taip gaudo planktoninius organizmus.

Gyvena ant uolų, banginių, vėžlių ir kitų jūros gyvūnų, gausiai padengia laivo povandeninę dalį. Daugiausia minta planktonu. Yra parazitinių rūšių. Nors randami iki 600 metrų gylio, labiau mėgsta seklias vietas, taip pat ir tokias kur atoslūgio metu atsidengia dugnas (taip gyvenantys ūsakojai gerai prisitaikę kurį laiką prabūti ore).

Ūsakojai turi dvi lervos stadijas, nauplijų ir po jo sekantčią specifinę formą (vadinama cipridu). Nauplijaus stadija ilga, ji tęsiasi apie šešis mėnesius kurių metu gyvūnas maitinasi ir auga. Cipridas yra trumpa, nesimaitinanti prieš-suaugėlio stadija kurios pagrindinis tikslas - rasti tinkamą vietą galutiniam prisitvirtinimui. Cipridas ieško tinkamos vietos, liesdamas ir tirdamas paviršius savo pakitusiomis antenulėmis. Senkant atsargoms (ši stadija trunka daugiausa keletą savaičių) jis pamažu tampa mažiau išrankus. Radęs tinkamą vietą, cipridas prisitvirtina ir prasideda galutinė metamorfozė į suaugusį ūsakojį.

Kai kurie ūsakojai valgomi ir laikomi delikatesais.

Sprogkāji (Cirripedia) ir tekostraku apakšklases infraklase. Sprogkāji pārsvarā ir jūras formas (retāk dzīvo iesāļūdeņos). Tie pieaugušā stāvoklī ir piestiprinājušies pie substrāta un nevar aktīvi pārvietoties. Neparazītiskie sprogkāji piestiprinās pie zemūdens klintīm un akmeņiem, bet dažos gadījumos pie jūrā peldošiem priekšmetiem, kā, piemēram, pie kuģu zemūdens daļām. Parazītiskie sprogkāji, kas pieder pie sakņgalvju apakškārtas, sasnieguši galēju vienkāršotības pakāpi ārējā uzbūvē un parazitē uz augstākajiem vēžiem. Sakarā ar sēdošo dzīves veidu sprogkāji pilnīgi kļuvuši par hermafrodītiem.

Par sprogkāju piederību pie vēžveidīgajiem liecina to attīstība: tiem ir nauplija un metanauplija kāpura fāzes. Sprogkājvēži pieaugušā fāzē visvairāk ir novirzījušies no vēžveidīgo tipiskās uzbūves, tāpēc sākotnēji bija problēmas sprogkāju izpētē. Cietā kaļķa čaula, pastāvīgs sēdošs dzīvesveids un vēžveidīgo ārējo morfoloģisko īpašību trūkums traucēja to sistemātiskā stāvokļa noteikšanu. Pat tāds izcils zoologs kā Ž. Kivjē pieskaitīja sprogkājus pie moluskiem. Lamarks uzskatīja sprogkājus par pārejas formu starp tārpiem un moluskiem. Tikai 1830. gadā, kad tika izpētīti sprogkāju kāpuri, kas morfoloģiski ir līdzīgi citiem vēžveidīgo kāpuriem, tika pierādīta sprogkāju piederība pie vēžveidīgajiem.

Pasaulē ir zināmas ap 1220 sprogkāju sugas.

Infraklase Sprogkāji (Cirripedia)

Sprogkāji (Cirripedia) ir tekostraku apakšklases infraklase. Sprogkāji pārsvarā ir jūras formas (retāk dzīvo iesāļūdeņos). Tie pieaugušā stāvoklī ir piestiprinājušies pie substrāta un nevar aktīvi pārvietoties. Neparazītiskie sprogkāji piestiprinās pie zemūdens klintīm un akmeņiem, bet dažos gadījumos pie jūrā peldošiem priekšmetiem, kā, piemēram, pie kuģu zemūdens daļām. Parazītiskie sprogkāji, kas pieder pie sakņgalvju apakškārtas, sasnieguši galēju vienkāršotības pakāpi ārējā uzbūvē un parazitē uz augstākajiem vēžiem. Sakarā ar sēdošo dzīves veidu sprogkāji pilnīgi kļuvuši par hermafrodītiem.

Par sprogkāju piederību pie vēžveidīgajiem liecina to attīstība: tiem ir nauplija un metanauplija kāpura fāzes. Sprogkājvēži pieaugušā fāzē visvairāk ir novirzījušies no vēžveidīgo tipiskās uzbūves, tāpēc sākotnēji bija problēmas sprogkāju izpētē. Cietā kaļķa čaula, pastāvīgs sēdošs dzīvesveids un vēžveidīgo ārējo morfoloģisko īpašību trūkums traucēja to sistemātiskā stāvokļa noteikšanu. Pat tāds izcils zoologs kā Ž. Kivjē pieskaitīja sprogkājus pie moluskiem. Lamarks uzskatīja sprogkājus par pārejas formu starp tārpiem un moluskiem. Tikai 1830. gadā, kad tika izpētīti sprogkāju kāpuri, kas morfoloģiski ir līdzīgi citiem vēžveidīgo kāpuriem, tika pierādīta sprogkāju piederība pie vēžveidīgajiem.

Rankpootkreeften (Cirripedia) behoren tot de kreeftachtigen. De leden van deze infraklasse zijn lang aangezien voor weekdieren. De lichaamsbouw van de volwassen dieren lijkt op het eerste gezicht totaal niet op die van geleedpotigen. In 1830 heeft men ontdekt dat de rankpootkreeften wel degelijk tot de kreeftachtigen behoren. Hun larvale ontwikkeling is typisch voor die van geleedpotigen. Bij de overgang van larve naar volwassen dier gaan de larven zich vasthechten en/of ingraven. De kreeftachtige ondergaat zulk een grondige metamorfose, dat er nauwelijks nog een overeenkomst te bespeuren is tussen het volwassen dier en de larve. Ze hebben naar verhouding de langst bekende penissen van alle dieren, gemiddeld 7x langer dan hun lichaam.[1]

Rankpootkreeften (Cirripedia) behoren tot de kreeftachtigen. De leden van deze infraklasse zijn lang aangezien voor weekdieren. De lichaamsbouw van de volwassen dieren lijkt op het eerste gezicht totaal niet op die van geleedpotigen. In 1830 heeft men ontdekt dat de rankpootkreeften wel degelijk tot de kreeftachtigen behoren. Hun larvale ontwikkeling is typisch voor die van geleedpotigen. Bij de overgang van larve naar volwassen dier gaan de larven zich vasthechten en/of ingraven. De kreeftachtige ondergaat zulk een grondige metamorfose, dat er nauwelijks nog een overeenkomst te bespeuren is tussen het volwassen dier en de larve. Ze hebben naar verhouding de langst bekende penissen van alle dieren, gemiddeld 7x langer dan hun lichaam.

Rankeføttinger eller rankefotinger er en gruppe krepsdyr som omfatter blant annet andeskjellfamilien og rur. De lever i hav, og finnes oftest på grunt vann og i tidevannssonen.

Av såkalte «langhalser» (Penduculata) er den viktigste slekten i nordlige farvann Scalpellum hvorav 7 arter holder til i Norskehavet og/eller langs norskekysten, mens slektene Calantica (Island) og Pollicipes (Kanalen, Biskaya) er observert i Nord-Atlanteren men ikke i norske farvann.[1] Arten Trypetesa lampas er observert i Norskehavet, Nordsjøen, Kattegat, ved De britiske øyer og ned til Middelhavet, mens Weltneria exargilla er observert i Biskayabukta på 1500 meters dyp.[2]

Andre slekter av rur og andre krepsdyr som tidvis henføres til den store gruppen av rankeføttinger, og som lever i nordlige farvann, inkluderer Lepas med 5 arter i Nord-Atlanteren og/eller norske farvann, og videre enkeltarter av slektene Anelasma, Conchoderma, Alepas, Verruca, Chthamalus, Coronula, Xenobalanus, Platylepas, Stomatolepas, Bathylasma, Chirona, Acasta, Elminius, Semibalanus og Pyrgoma. I tillegg finner vi i Atlanteren og nordlige strøk minst 9 arter i rur-slekten Balanus samt minst en art av Solidobalanus og muligens to arter av Megabalanus.[3]

Av gruppen «rotfotinger» (Rhizocephala) finner vi i nordlige farvann slektene Briarosaccus, Peltogaster, Peltogasterella, Galatheascus, Parthenopea, Tortugaster, Trachelosaccus, Cyphosaccus, en rekke arter av Sacculina, og et fåtall arter av Drepanorchis, Lernaeodiscus, Triangulus, Clistosaccus, Sylon, Chtamalophilus, Boschmaella, Duplorbis, og Polysaccus.[4]

Av overorden Facetotecta finnes liknende i nordlige farvann arter av slektene Ascothorax, Isidascus, Synagoga, Ulophysema, minst 7 arter av slekten Dendrogaster, og videre arter av Laura og Baccaleureus.[5]

Taksonomien til Maximillopoda er komplisert og under har vært revisjon ettersom ny innsikt vinnes. Det er generelt omstridt å fin-inndele organismer taksonomisk. En vanlig oppdeling anerkjenner Maxllopoda som en av seks ulike klasser av krepsdyr, der forøvrig storkreps (Malacostraca) er den mest artsrike gruppen - etterfulgt av Maxillopoda. En moderne oppdatering av systematikken gis av Martin og Davis[6], som følgende oversikt følger ned til nivået orden, mens lavere nivåer i enkelte tilfeller følger Catalogue of Life:[7]

Rankeføttinger eller rankefotinger er en gruppe krepsdyr som omfatter blant annet andeskjellfamilien og rur. De lever i hav, og finnes oftest på grunt vann og i tidevannssonen.

Av såkalte «langhalser» (Penduculata) er den viktigste slekten i nordlige farvann Scalpellum hvorav 7 arter holder til i Norskehavet og/eller langs norskekysten, mens slektene Calantica (Island) og Pollicipes (Kanalen, Biskaya) er observert i Nord-Atlanteren men ikke i norske farvann. Arten Trypetesa lampas er observert i Norskehavet, Nordsjøen, Kattegat, ved De britiske øyer og ned til Middelhavet, mens Weltneria exargilla er observert i Biskayabukta på 1500 meters dyp.

Andre slekter av rur og andre krepsdyr som tidvis henføres til den store gruppen av rankeføttinger, og som lever i nordlige farvann, inkluderer Lepas med 5 arter i Nord-Atlanteren og/eller norske farvann, og videre enkeltarter av slektene Anelasma, Conchoderma, Alepas, Verruca, Chthamalus, Coronula, Xenobalanus, Platylepas, Stomatolepas, Bathylasma, Chirona, Acasta, Elminius, Semibalanus og Pyrgoma. I tillegg finner vi i Atlanteren og nordlige strøk minst 9 arter i rur-slekten Balanus samt minst en art av Solidobalanus og muligens to arter av Megabalanus.

Av gruppen «rotfotinger» (Rhizocephala) finner vi i nordlige farvann slektene Briarosaccus, Peltogaster, Peltogasterella, Galatheascus, Parthenopea, Tortugaster, Trachelosaccus, Cyphosaccus, en rekke arter av Sacculina, og et fåtall arter av Drepanorchis, Lernaeodiscus, Triangulus, Clistosaccus, Sylon, Chtamalophilus, Boschmaella, Duplorbis, og Polysaccus.

Av overorden Facetotecta finnes liknende i nordlige farvann arter av slektene Ascothorax, Isidascus, Synagoga, Ulophysema, minst 7 arter av slekten Dendrogaster, og videre arter av Laura og Baccaleureus.

Wąsonogi (Cirripedia) – gromada[2][3][4], podgromada[5] lub infragromada[6][7] skorupiaków wyłącznie morskich. Jedyna grupa, która obejmuje stawonogi osiadłe. Zamieszkują przeważnie płytkie, przybrzeżne wody, osiadając na obiektach podwodnych, skałach, koralowcach, muszlach mięczaków, pancerzach skorupiaków, na portowych urządzeniach, czy zanurzonych w wodzie częściach statków. Wiele z nich odbywa wędrówki, przyczepione do ciała żółwi morskich czy rekinów. Większość z nich występuje masowo, a 400-2500 osobników na 1 m2 nie należy do rzadkości. Niektóre gatunki wiercą w szkieletach koralowców i muszlach mięczaków, szukając schronienia. Wiele wąsonogów jest pasożytami skorupiaków i wyższych osłonic. Niektóre żyją w komensalizmie z rybami (najczęściej żarłaczami) lub wielorybami. Obejmują ok. 1000 bardzo wyspecjalizowanych gatunków[3].

Przeciętna długość postaci dojrzałych wynosi 3-4 cm, wyjątkowo do 80 cm (u osiadłych). Ciało silnie zmodyfikowane w zależności od trybu życia, szczególnie formy osiadłe i pasożyty odbiegają budową od typowych skorupiaków[3].

Wąsonogi posiadają bardzo długie penisy osiągające 15 cm długości - jest to największy znany stosunek długości penisa do długości ciała wśród organizmów żywych[8].