en

names in breadcrumbs

El virus de la malaltia hemorràgica del conill (VEHC) pertany al gènere Largovirus, concretament a la família Caliciviridae. Existeixen diverses soques víriques de VEHC amb diferentes característiques epidemiològiques, patològiques i genètiques. No obstant, només es coneix un serotip amb els seus dos subtipus principals: el VEHC i la seva variant antigènica VEHCa.

Aquest virus afecta únicament a membres domèstics i silvestres de l' espècie Oryctolagus cuniculus causant la malaltia de la febre hemorràgica en conills (EHC). La malaltia de la febre hemorràgica en conills és una malaltia aguda, altament contagiosa i d’elevada mortalitat entre conills domèstics i silvestres. Es caracteritza per causar mort sobtada i problemes respiratoris severs.[1]

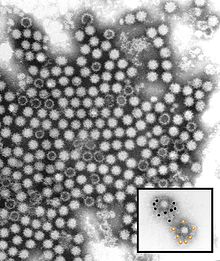

Del llatí calix "copa", això fa referència al fet que aquesta família de virions presenten unes depressions en forma de copa en observar-los al microscopi electrònic. Una altra caracterísitca destacable és que tenen una càpside de simetria icosaèdrica de mida petita (oscil·la sobre els 40nm de diàmetre), i el seu àcid nucleic és ARN monocatenari positu.[2]

El VEHC és classificat com un Calcivirus molt estable, sense embolcall i d'uns 32-35 nm de diàmetre. Consta d'un genoma d'ARN no segmentat, monocatenari positiu ( 7437 kb). Aquest, es troba contingut en una càpside de forma icosaèdrica, constituïda per 180 molècules de proteïna associades a una proteïna capsídica principal. La proteïna de la càspide (VP60) del virus es plega en dos dominis diferents: domini intern (inclou l’extrem N-terminal) i domini extern (inclou l’extrem C-terminal) que es mantenen units mitjançant una regió frontissa.[3]

D’aquesta manera el genoma es troba organitzat en dos grans ORFs (marcs oberts de lectura). D’una banda l’ORF1, el qual codifica la poliproteïna no estructural, amb el principal gen CP estructural (VP60), i la seqüència de poliproteïna no estructural Cody. D’altra banda superposat a ORF1, trobem ORF2 que codifica una petita proteïna (VP10) de funció desconeguda.

Tot i pertànyer al gènere dels Largovirus, l'agent etiològic difereix respecte a aquest, antigènicament guarda relació amb el virus d'elevada morbiditat i mortalitat EHC.

El virus es transmet ràpidament per contacte amb animals infectats (a través de via oral, nasal, conjuntival) així com per fòmits. L’entrada del virus a la cèl·lula hoste es produeix per unió amb els corresponents receptors de membrana, donant lloc a l'endocitosi del virus dintre de la cèl·lula.

La replicació vírica del VEHC és citoplasmática, és a dir, fora del nucli de la cèl·lula hoste.

Cal destacar la resistència que presenta el virus a la seva inactivació, si es troba protegit per material orgànic pot romandre mesos infectiu. També oposa una elevada resistència davant dels processos de congelació.[4]

El 1984 una nova malaltia altament infecciosa del conill europeu, Oryctolagus cuniculus, va ser identificada a la Xina. Aquesta, estava caracteritzada per la presència de lesions hemorràgiques particularment als pulmons i al fetge dels animal, així doncs, va ser anomenada la malaltia hemorràgica del conill. En els primers 6 mesos, el virus va acabar amb uns 470.000 conills i, a finals del 1990, ja s'havien registrat altres brots en 40 països més. La malaltia hemorràgica del conill (EHC) s'havia tornat endèmica a les poblacions de conills silvestres d'Europa, Australia i Nova Zelanda.

A Europa, no tenien clar quin era el virus causant de la EHC, ja que confonien aquest virus amb el virus causant d'una malaltia antigènicament molt similar anomenada "síndrome de la llebre parda europea". Aquesta síndrome havia estat reconeguda a principis del 1980, afectant a Lepus Europaeus i conseqüentment a altres Lepus spp. Finalment, es va acabar diferenciant, ja que es va veure que, la malaltia hemorràgica del conill és causada per un calicivirus que té una forma diferent a la de l'altre virus. [5]

El virus es transmet per contacte directe amb animals infectats i també per fòmits.

Des d’un punt de vista patogènic, els conills poden adquirir aquesta malaltia per via oral (fecoral), que és la via de contaminació principal, seguida de la conjuntiva i la respiratòria. La majoria de les excrecions de l'animal afectat (orina, femtes i secrecions respiratòries) poden contenir el virus. El VEHC també pot adquirir-se per contacte amb un cadàver o amb el pèl d’un animal infectat.

Les mosques i altres insectes són vectors mecànics molt eficients, només necessiten uns pocs virions per infectar un conill per via conjuntival. El VEHC pot romandre a l'interior del vector durant uns 9 dies, permetent la seva propagació a altres zones. Els animals silvestres poden transmetre'l mecànicament.

Tot i que la replicació del virus no es dóna en depredadors o carronyaires, aquests també poden excretar el virus en les femtes després d'haver-se alimentat de conills infectats.

Aquest virus és molt resistent quan es troba protegit dins dels teixits i també suporten cicles de congelació i descongelació. [6]

El període d’incubació és el més curt comparat amb les diferents patologies que afecten a conills (entre 1 i 3 dies). La malaltia hemorràgica del conill afecta amb signes clínics greus a animals majors de dos mesos d’edat. Curiosament els conills amb menys de dos mesos d’edat no desenvolupen una malaltia crítica després de la infecció i a més en queden immunitzats. La malaltia es pot presentar de diferents formes; aguda, hiperaguda, que són les més freqüents, però també subaguda i crònica.

La malaltia, en la seva forma hiperaguda, es caracteritza per causar una mort sobtada després d'un període d'entre 6 a 24 hores de depressió i febre, amb els següents símptomes: xiscles terminals seguits de col·lapse i mort.

En les formes de presentació aguda i subaguda, s'observa embotiment, anorèxia, congestió de la conjuntiva palpebral i signes neurològics (falta de coordinació, excitació i moviment de pedaleig), també es caracteritzen per causar abundants hemorràgies nasals. A vegades, també apareixen signes respiratoris com dispnea, cianosi i rinorrea nasal terminal. El llagrimeig, hemorràgies oculars o epistaxis també es pot observar en alguns casos.

Aquesta simptamatologia serveix tant per la malaltia aguda com la subaguda, la diferència, és que en la subaguda són símptomes de caràcter més lleu i la probabilitat que els conills sobrevisquin és major. Per últim, cal comentar, que es creu que la forma crònica d'aquesta malaltia, és asimptomàtica.[7]

Aquest virus provoca un retràs en la coagulació sanguina, lligada a la necrosi hepàtica, i hemorràgies en forma de petèquies i equimosis en la majoria dels òrgans. En la majoria dels casos també trobem una marcada esplenomegàlia, tumefaccions i hemorràgies al timus.

Al realitzar la necròpsia les lesions més importants les trobem al fetge, tràquea i pulmons. Als pulmons, observem una congestió i hemorràgia que produeix un accentuat marcatge dels lòbuls. A la tràquea també observem hemorragies i una mucosa congestiva, amb exsudat espumós sanguinolent com a conseqüència d'un edema pulmonar.

Si l'animal afectat es trobava gestant en el moment de la mort, al fer la necropsia, és freqüent observar la presència d'hemorragies en els fetus i l'úter.

En alguns animals que han superat la malaltia, es poden trobar lesions digestives tals com: gastritis catarral, enteritis catarral, enteritis necròtica i tumefacció dels ganglis mesentèrics.[5]

El fetge és l'òrgan més afectat amb necrosi aguda multifocal. Les lesions focals poden reduir-se a grups d'hepatòcits o ser més extenses si es dóna confluència de diversos focus. També, als sinusoides hepàtics, hi ha presència de microtrombos i cúmuls en els limfòcits i granulòcits creant una inflamació.[6]

En tràquees i pulmons trobem microtrombos a nivell dels capil·lars, causant d’edema pulmonar.

A la resta d’òrgans i teixits és freqüent observar cariorrexis (esclat del nucli cel·lular donant restes basòfiles microscòpicament observables) del teixit limfoide. I microtrombos destacables als glomèruls renals.

Taxes de morbiditat del 100% i taxes de mortalitat del 90% són observades en conills més vells de 2 mesos.[8]

El VEHC encara no ha sigut cultivat in vitro, però en els teixits infectats dels conills hi ha altes concentracions d’aquest. Aquest recurs ha sigut utilitzat freqüentment per obtenir antigens virals per a un test de diagnòstic.

Els mètodes utilitzats són proves de reacció en cadena (polimerasa de transcripció inversa), immunotrasferència, microscòpia immunoelectrònica de tinció negativa, immunocoloració o ELISA. Abans s’utilitzava la virus hemaglutinació dels eritròcits humans; un immunoassaig enzimàtic i immunofluorescència també són utilitzades per al diagnòstic, però són menys específiques i sensibles (donen més falsos positius i negatius).[7]

La inoculació experimental a altres conills sensibles comparada amb un grup control prèviament immunitzat, també pot ajudar a identificar la presència del virus.

Les vacunes per al control de la malaltia són preparades com un inactivat homogènic del teixit infectat dels conills barrejat amb adjuvant, les partícules semblants al virus produïdes per tecnologia d’ADN recombinant en sistemes d’expressió de baculovirus són efectives en alguns casos, però encara no estan disponibles comercialment.

El virus de la malaltia hemorràgica del conill és altament contagiós, però es pot aconseguir la seva erradicació mitjançant la despoblació, desinfecció, vigilancia i cuarentenes.

Aquest virus és molt resistent però el podem inactivar mitjançant hidròxid de sodi al 10% o formol al 1 o 2%, entre altres desinfectants.

Els cadàvers han de ser retirats immediatament i eliminar-se de forma segura. Les granges afectades hauran de repoblar-se passat un cert temps, ja que el VEHC pot romandre per un temps en l'ambient, especialment si està protegit per teixits.[6]

Existeix una vacuna estàndard contra el VEHC, però els investigadors busquen alternatives que millorin la tècnica, és a dir, que incloguin únicament antígens purificats del virus. Per aconseguir-ho es duen a terme tècniques de biologia molecular, gràcies a les quals es va identificar la proteïna VP60 de la càpside del VEHC. La inoculació d’aquesta proteïna a conills els proporciona immunitat, ja que és una proteïna antigènica. Aquesta pot ser extreta directament del virus en qüestió o mitjançant alternatives, com que altres microorganismes la produeixin. Això passa amb un baculovirus dels mosquits (es tracta de recombinació). A França s’utilitza combinada amb el virus de la mixomatosi, però s’està treballant amb la possibilitat d'introduir la proteïna VP60 al genoma del virus de mixomatosi vacunal. L'objectiu és poder vacunar els conills enfront ambdues malalties, amb una vacuna mixta i una única administració.[7]

En granges indemnes (la malaltia no ha estat present durant un mínim de 3 anys) es recomana un programa de vacunació consistent a una única dosis als 3 - 3,5 mesos de vida de l’animal. En el cas que el veterinari sospiti d’una ruptura d’immunitat cal efectuar una revacunació. No és recomanable vacunar als llorigons atès que hi hagi risc d’infecció, a més si existeix aquest risc, la vacunació dels futurs reproductors s’avançarà als 2-2,5 mesos.

En les granges on apareix la malaltia es procedeix a una vacunació d’urgència a tots els conills en risc. Si només es vacuna la reposició, cal revacunar les femelles de més de 5 parts i els mascles de més d’1 any. Pel que fa als llorigons és recomanable vacunar-los al deslletament (la millor opció és vacunar tots aquells que es deslleten durant el mes següent a la detecció del problema), però amb una dosis menor que la dels adults.

El virus de la malaltia hemorràgica del conill (VEHC) pertany al gènere Largovirus, concretament a la família Caliciviridae. Existeixen diverses soques víriques de VEHC amb diferentes característiques epidemiològiques, patològiques i genètiques. No obstant, només es coneix un serotip amb els seus dos subtipus principals: el VEHC i la seva variant antigènica VEHCa.

Aquest virus afecta únicament a membres domèstics i silvestres de l' espècie Oryctolagus cuniculus causant la malaltia de la febre hemorràgica en conills (EHC). La malaltia de la febre hemorràgica en conills és una malaltia aguda, altament contagiosa i d’elevada mortalitat entre conills domèstics i silvestres. Es caracteritza per causar mort sobtada i problemes respiratoris severs.

Králičí mor je smrtelné virové onemocnění (z čeledi Caliciviridae) postihující králíky, proti němuž se lze účinně chránit vakcinací. K nakažení dochází přímým kontaktem s nakaženým jedincem nebo bodnutím komárem nebo jiným bodavým hmyzem. Po krátké inkubační době má nemoc rychlý průběh a králík umírá v křečích s příznaky dušení.

Šíří se prachem, aerosolem a všemi myslitelnými cestami - počínajíc vzdušným prouděním, zvířaty, hmyzem, materiály, dopravními prostředky na velké vzdálenosti. V našich podmínkách není výskyt sezónní, nákaza se může objevit v létě, stejně jako za mrazivé zimy. Rozšíření může ovlivnit vítr, který v případě sucha kontaminovaný prach roznese i na velké vzdálenosti. Je velmi odolný a odolává i vysokým mrazům.

Terapie neexistuje, nemoci se dá předejít jen preventivní vakcinací.

Králičí mor je smrtelné virové onemocnění (z čeledi Caliciviridae) postihující králíky, proti němuž se lze účinně chránit vakcinací. K nakažení dochází přímým kontaktem s nakaženým jedincem nebo bodnutím komárem nebo jiným bodavým hmyzem. Po krátké inkubační době má nemoc rychlý průběh a králík umírá v křečích s příznaky dušení.

Šíří se prachem, aerosolem a všemi myslitelnými cestami - počínajíc vzdušným prouděním, zvířaty, hmyzem, materiály, dopravními prostředky na velké vzdálenosti. V našich podmínkách není výskyt sezónní, nákaza se může objevit v létě, stejně jako za mrazivé zimy. Rozšíření může ovlivnit vítr, který v případě sucha kontaminovaný prach roznese i na velké vzdálenosti. Je velmi odolný a odolává i vysokým mrazům.

Terapie neexistuje, nemoci se dá předejít jen preventivní vakcinací.

Die Chinaseuche (wissenschaftliche Namen: Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease (kurz RHD[1][2]), Rabbit Calicivirus Disease (kurz RCD), Viral Haemorrhagic Disease (kurz VHD) oder „Bunny Ebola“ („Kaninchen-Ebola“)[3]) ist eine für die Veterinärmedizin unheilbare hämorrhagische Viruserkrankung,[1] die ausschließlich Kaninchen befällt. Verursacher der Chinaseuche sind Caliciviren aus der Gattung Lagovirus, der als Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (RHDV) bezeichnet wird.[1] Die größte Verbreitung haben die Stämme RHDVa und RHDV-2 (auch RHD-V 2 genannt).[4] Empfänglich sind alle Kaninchenrassen beiderlei Geschlechts. Jungtiere bis zu etwa einem Monat erkranken meist nicht,[1] können aber den Erreger vermehren. Die meisten erkrankten Tiere sind älter als 3 Monate. Die Mortalität liegt je nach Virusstamm bei 5 bis 100 Prozent. Die seit 2016 zu beobachtenden Erkrankungen verlaufen fast immer tödlich.

1984 trat die bis dahin nicht bekannte Erkrankung erstmals bei Angorakaninchen in der Volksrepublik China auf[5], anderen Quellen zufolge bei Haus- und Farmkaninchen, die aus Deutschland stammten.[1][6] Sie hat sich weltweit verbreitet. Bereits 1986 wurde der Symptomkomplex in Westeuropa beobachtet; das Virus wurde vermutlich durch Zuchttiere, importiertes Kaninchenfleisch oder Kaninchenwolle eingeschleppt. 1988 kam sie erstmals in Deutschland vor.[1]

Die Chinaseuche kommt auf der gesamten Nordhalbkugel mit Ausnahme des Baltikums und des Balkans sowie in Australien und Neuseeland vor. In Mittelamerika und Südamerika sind bislang keine Erkrankungen aufgetreten. Auch Südasien, Südostasien und weite Teile Afrikas (ausgenommen Tunesien, Ghana und Benin) sind RHD-frei.[3]

Der Krankheitserreger ist ein Calicivirus[1] mit ikosaedrischer Hülle und einem Durchmesser von etwa 40 Nanometern, das sogenannte Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (kurz RHDV, mit Referenzstamm Rabbit calicivirus, RCV), die Typusspezies der Gattung Lagovirus; die zweite (mit Stand März 2019) offiziell anerkannte Spezies dieser Gattung ist das European brown hare syndrome virus. Ende der 1990er-Jahre wurden in Deutschland und Italien ein genetisch abweichender Typ namens RHDVa gefunden. Im Oktober 2010 wurde in Nordwest-Frankreich ein weiterer Typ nachgewiesen, der auch bei geimpften Tieren eine Erkrankung auslöste. Diese RHD2 genannte Variante der Krankheit (Spitzname englisch bunny ebola), ausgelöst durch die RHDV-Variante Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus 2 (kurz RHDV2 oder RHDV-2) ist in Mitteleuropa (Frankreich, Deutschland) endemisch, breitet sich aber 2020 auch vom Nordwesten der USA und von Kanada in den Südwesten der USA und nach Mexiko immer weiter aus.[11][12] Zunächst wurde eine geringere Mortalität im Vergleich zum Originalstamm beschrieben.[13][14] RHD2 hat sich von Frankreich aus rapide über weite Teile Europas ausgebreitet. Dieses Virus gilt als „unberechenbar und aggressiv“ im Vergleich mit den bisherigen Varianten. Es kann auch Feldhasen infizieren. Ein neuer Impfstoff wurde in Spanien und Frankreich entwickelt.[15][16][17] Er ist aber in Deutschland seit Anfang 2017 erhältlich. Es gibt zahlreiche nah verwandte Caliciviren, die nicht krankheitsverursachend wirken, bei denen aber zumeist eine Kreuzimmunität mit dem RHDV besteht.[6] Für den Menschen ist RHD2 harmlos.[2]

Das RHDV ist im Blut, im Knochenmark, in allen Organen und in sämtlichen Ausscheidungen nachweisbar.[1] Somit kann die Infektion über direkten Kontakt oder indirekt über Stechinsekten und Fliegen erfolgen. Auch eine indirekte Übertragung über mit dem Virus behaftete Gegenständen (Futter, Kleidung, Käfiginventar) ist möglich. Das Virus bleibt in der Umwelt bei Zimmertemperatur über drei Monate ansteckend, bei niedrigen Umgebungstemperaturen siebeneinhalb Monate.[18]

Die Inkubationszeit von RHD liegt bei 1 bis 3 Tagen. Danach tritt ein akuter bis perakuter Verlauf ein, der im Allgemeinen innerhalb von 12 bis 48 Stunden zum Tod des Tieres führt. Typisch für den klinischen Verlauf sind zentralnervöse Symptome, vor allem Krämpfe. Die Kaninchen stoßen in ihrem Todeskampf einen hohen Schrei aus. Im Endstadium ist ein Überstrecken des Kopfes zum Rücken hin (Opisthotonus) recht typisch. Das RHD-Virus verursacht bei Kaninchen Blutgerinnungsstörungen, Blutungen in den Atemwegen mit Atemnot und Organschwellungen.[1]

Wesentliches Merkmal der Erkrankung ist eine hochgradige Störung der Blutgerinnung, die zu punktförmigen Blutungen (Petechien) in allen Geweben führt. Blutungen treten vor allem in den Atemwegen, in Magen, Darm und den Harnorganen auf. Dadurch kommt es zu einer starken Atemnot beim Kaninchen und zu Blut in den Ausscheidungen. Daneben tritt eine Leberentzündung mit Gewebsuntergang sowie Fibrosen und Verkalkungen der Leberzellen auf. Ein weiteres Anzeichen für die Krankheit kann apathisches Verhalten sein, das bald nach der Infektion auftritt.

Die Pathologie ist hinweisend auf eine Chinaseuche, aber nicht beweisend. Zur definitiven Diagnose ist ein Nachweis von Virusprotein mittels ELISA oder RT-PCR notwendig. Eine Anzüchtung in Zellkulturen ist bislang nicht möglich. Antikörperuntersuchungen sind aufgrund des perakuten Verlaufs ohne Bedeutung.[3]

RHD gilt nach heutigem Stand der Veterinärmedizin als unheilbar.[1] Die Bekämpfung der Krankheit geschieht am effektivsten durch eine jährlich zu wiederholende Impfung.[1] Inwieweit sich die neuen RHDV-Stämme dem Impfschutz durch die etablierten Impfstämme entziehen, ist bislang offen.[6] Seuchenhygienische Maßnahmen wie Quarantänisierung und Verbot von Kaninchenausstellungen in betroffenen Gebieten haben sich als sinnvoll erwiesen.

Zu Desinfektion müssen Desinfektionsmittel eingesetzt werden, die gegen unbehüllte Viren wirksam sind.[3]

Die Chinaseuche (wissenschaftliche Namen: Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease (kurz RHD), Rabbit Calicivirus Disease (kurz RCD), Viral Haemorrhagic Disease (kurz VHD) oder „Bunny Ebola“ („Kaninchen-Ebola“)) ist eine für die Veterinärmedizin unheilbare hämorrhagische Viruserkrankung, die ausschließlich Kaninchen befällt. Verursacher der Chinaseuche sind Caliciviren aus der Gattung Lagovirus, der als Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (RHDV) bezeichnet wird. Die größte Verbreitung haben die Stämme RHDVa und RHDV-2 (auch RHD-V 2 genannt). Empfänglich sind alle Kaninchenrassen beiderlei Geschlechts. Jungtiere bis zu etwa einem Monat erkranken meist nicht, können aber den Erreger vermehren. Die meisten erkrankten Tiere sind älter als 3 Monate. Die Mortalität liegt je nach Virusstamm bei 5 bis 100 Prozent. Die seit 2016 zu beobachtenden Erkrankungen verlaufen fast immer tödlich.

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD), also known as viral hemorrhagic disease (VHD), is a highly infectious and lethal form of viral hepatitis that affects European rabbits. Some viral strains also affect hares and cottontail rabbits. Mortality rates generally range from 70 to 100 percent.[4] The disease is caused by strains of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV), a lagovirus in the family Caliciviridae.

Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV) is a virus in the genus Lagovirus and the family Caliciviridae. It is a nonenveloped virus with a diameter around 35–40 nm, icosahedral symmetry, and a linear positive-sense RNA genome of 6.4–8.5 kb. RHDV causes a generalized infection in rabbits that is characterized by liver necrosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and rapid death. Division into serotypes has been defined by a lack of cross-neutralization using specific antisera.[5] Rabbit lagoviruses also include related caliciviruses such as European brown hare syndrome virus.[6]

RHDV appears to have evolved from a pre-existing avirulent rabbit calicivirus (RCV). Nonpathogenic rabbit caliciviruses related to, but distinct from RHDV, had been circulating, apparently harmlessly, in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand prior to the emergence of RHDV.[7][8] In the course of its evolution RHDV split into six distinct genotypes, all of which are highly pathogenic.[8]

The three strains of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus of medical significance are RHDV, RHDVa and RHDV2. RHDV (also referred to as RHDV, RHDV1, or as classical RHD) only affects adult European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). This virus was first reported in China in 1984,[9] from which it spread to much of Asia, Europe, Australia, and elsewhere.[10] A few isolated outbreaks of RHDV have occurred in the United States and Mexico, but they remained localized and were eradicated.

In 2010, a new lagovirus with a distinct antigenic profile was identified in France. The new virus, named rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus type 2 (abbreviated as RHDV2 or RHDVb), also caused RHD, but exhibited distinctive genetic, antigenic, and pathogenic features. Importantly, RHDV2 killed rabbits previously vaccinated with RHDV vaccines, and affected young European rabbits, as well as hares (Lepus spp.).[11] All these features strongly suggest that the virus was not derived from RHDVa, but from some other unknown source.[4] RHDV2 has since spread to the majority of Europe, as well as to Australia, Canada,[12] and the United States.[13][14]

Both viruses causing RHD are extremely contagious. Transmission occurs by direct contact with infected animals, carcasses, bodily fluids (urine, feces, respiratory secretions), and hair. Surviving rabbits may be contagious for up to 2 months.[6] Contaminated fomites such as clothing, food, cages, bedding, feeders, and water also spread the virus. Flies, fleas, and mosquitoes can carry the virus between rabbits.[10] Predators and scavengers can also spread the virus by shedding it in their feces.[10] Caliciviruses are highly resistant in the environment, and can survive freezing for prolonged periods. The virus can persist in infected meat for months, and for prolonged periods in decomposing carcasses. Importation of rabbit meat may be a major contributor in the spread of the virus to new geographic regions.[6]

RHD outbreaks tend to be seasonal in wild rabbit populations, where most adults have survived infection and are immune. As young kits grow up and stop nursing, they no longer receive the antibodies provided in their mother's milk and become susceptible to infection. Thus, RHD epizootics occur more often during the rabbits' breeding season.[10]

Generally, high host specificity exists among lagoviruses.[6] Classic RHDVa only affects European rabbits, a species native to Europe and from which the domestic rabbit is descended. The new variant RHDV2 affects European rabbits, as well, but also causes fatal RHD in various Lepus species, including Sardinian Cape hares (L. capensis mediterraneus), Italian hares (L. corsicanus), and mountain hares (L. timidus).[15] Reports of RHD in Sylvilagus species have been coming from the current outbreak in the United States.[16]

RHD caused by RHDV and RHDVa demonstrates high morbidity (up to 100%) and mortality (40-100%) in adult European rabbits. Young rabbits 6–8 weeks old are less likely to be infected, and kits younger than 4 weeks old do not become ill.[6] The more recently emerged RHDV2 causes death and disease in rabbits as young as 15 days old. Mortality rates from RHDV2 are more variable at 5-70%. Initially less virulent, the pathogenicity of RHDV2 has been increasing and is now similar to that found with RHDV and RHDVa. Deaths from RHDV2 have been confirmed in rabbits previously vaccinated against RHDVa.[6]

These viruses replicate in the liver and by mechanisms not fully elucidated, trigger the mass death of hepatocytes which can in turn lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation, hepatic encephalopathy, and nephrosis.[10] Bleeding may occur, as clotting factors and platelets are used up.

The incubation period for RHDVa is 1–2 days, and for RHDV2 3–5 days. Rabbits infected with RHDV2 are more likely to show subacute or chronic signs than are those infected with RHDVa.[6] In rabbitries, an epidemic with high mortality rates in adult and subadult rabbits is typical.[10] If the outbreak is caused by RHDV2, then deaths also occur in young rabbits.

RHD can vary in the rate clinical signs occur. In peracute cases, rabbits are usually found dead with no premonitory symptoms.[15] Rabbits may be observed grazing normally immediately before death.[10]

In acute cases, rabbits are inactive and reluctant to move. They may develop a fever up to 42 °C (107.6 °F) and have increased heart and respiratory rates. Bloody discharge from the nose, mouth, or vulva is common, as is blood in the feces or urine. Lateral recumbency, coma, and convulsions may be observed before death.[10] Rabbits with the acute form generally die within 12 to 36 hours from the onset of fever.[15]

Subacute to chronic RHD has a more protracted clinical course, and is more commonly noted with RHDV2 infections. Clinical signs include lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, and jaundice. Gastrointestinal dilation, cardiac arrhythmias, heart murmurs, and neurologic abnormalities can also occur.[6] Death, if it occurs, usually happens 1–2 weeks after the onset of symptoms, and is due to liver failure.[15]

Not all rabbits exposed to RHDVa or RHDV2 become overtly ill. A small proportion of infected rabbits clears the virus without developing signs of disease.[10] Asymptomatic carriers also occur, and can continue to shed virus for months, thereby infecting other animals. Surviving rabbits develop a strong immunity to the specific viral variant with which they were infected.[6]

A presumptive diagnosis of RHD can often be made based on clinical presentation, infection pattern within a population, and post mortem lesions. Definitive diagnosis requires detection of the virus. As most caliciviruses cannot be grown in cell culture, antibody and nucleic acid based methods of viral detection are often used.[6]

Complete blood counts from rabbits with RHD often show low levels of white blood cells and platelets, and chemistry panels show elevated liver enzymes. Evidence of liver failure may also be present, including increased bile acids and bilirubin, and decreased glucose and cholesterol. Prolonged prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times are typical. Urinalysis can show bilirubinuria, proteinuria, and high urinary GGT.[6]

The classic post mortem lesion seen in rabbits with RHD is extensive hepatic necrosis. Multifocal hemorrhages, splenomegaly, bronchopneumonia, pulmonary hemorrhage or edema, and myocardial necrosis may sometimes also be seen.[6]

RT-qPCR tests are a commonly used and accurate testing modality for RNA-based viruses. Other tests used include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, electron microscopy, immunostaining, Western blot, and in situ hybridization.[6] The tissue of choice for molecular testing is fresh or frozen liver, as it usually contains the largest numbers of virus, but if this is not available, spleen and serum can also be used. Identification of the strain of RHDV is needed so vaccination protocols can be adjusted accordingly.

A number of vaccines available against RHD are sold in countries where the disease is endemic. All provide 12 months of protection against RHD viruses. Because RHD viruses cannot normally be grown in vitro,[17] how these vaccines are produced is affected. Inactivated RHD vaccines, including Eravac,[18] Felavac, and Cylap, are “liver-derived”, meaning that laboratory rabbits are intentionally infected with RHD and their livers and spleens harvested to make vaccines. Each rabbit used results in the production of thousands of vaccine doses. This has led to controversy among rabbit lovers, who question the ethics of some rabbits having to die to protect others[19] but is not an issue where rabbits are primarily farmed for meat. Another method of reproducing the virus is through recombinant technology, where antigenic portions of the RHD viruses are inserted into viruses that can be grown in culture. This is the method used to create Nobivac Myxo-RHD PLUS.[20]

Vaccines against only the classic RHDVa strain are: Cylap RCD Vaccine, made by Zoetis,[21] protects rabbits from two different strains of RHDVa (v351 and K5) that are used for wild rabbit control in Australia.[22] CUNIPRAVAC RHD®,[23] manufactured by HIPRA, protects against the RHDVa strains found in Europe. Nobivac Myxo-RHD,[24] made by MSD Animal Health, is a live myxoma-vectored vaccine that offers one-year duration of immunity against both RHDVa and myxomatosis.

Vaccines against only the newer RHDV2 strain are: Eravac vaccine, manufactured by HIPRA,[25] protects rabbits against RHDV2 for a year.

Vaccines that protect against both RHDVa and RHDV2 strains include: Filavac VHD K C+V,[26] manufactured by Filavie, protects against both classical RHDVa and RHDV-2.[27] It is available in single dose and multidose vials. A soon-to-be-released vaccine from MSD Animal Health, Nobivac Myxo-RHD PLUS, is a live recombinant vector vaccine active against both RHDVa and RHDV2, as well as myxomatosis.[28]

Countries in which RHD is not considered endemic may place restrictions on importation of RHDV vaccines. Importation of these vaccines into the United States can only be done with the approval of the United States Department of Agriculture[29] and the appropriate state veterinarian.[30]

Caliciviruses are stable in the environment and difficult to inactivate. Products commonly used for household disinfection such as Clorox® and Lysol® disinfecting wipes do not work against these viruses. One effective option is to wipe down surfaces with a 10% bleach solution, allowing 10 minutes of contact time before rinsing. Other disinfectants shown to work include 10% sodium hydroxide, 2% One-Stroke Environ®, Virkon® S, Clorox® Healthcare Bleach Germicidal Wipes, Trifectant®, Rescue®, and hydrogen peroxide cleaners. Surface debris must always be mechanically removed prior to disinfection. A list of disinfectants that are effective against calicivirus (in this case norovirus) can be found on the Environmental Protection Agency's website.[31] Studies have shown that many quaternary ammonium compound based disinfectants do not inactivate caliciviruses.[32]

Because of the highly infectious nature of the disease, strict quarantine is necessary when outbreaks occur. Depopulation, disinfection, vaccination, surveillance, and quarantine are the only way to properly and effectively eradicate the disease. Deceased rabbits must be removed immediately and discarded in a safe manner. Surviving rabbits should be quarantined or humanely euthanized. Test rabbits may be used to monitor the virus on vaccinated farms.[33]

RHD is primarily a disease affecting European rabbits, which are native to the Iberian Peninsula and are found in the wild in much of Western Europe. Domesticated breeds are farmed throughout the world for meat and fur, and are becoming increasingly popular pets. European rabbits have been introduced to and become feral and sometimes invasive in Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Argentina, and various islands.[8]

RHD was first reported in 1984 in the People's Republic of China. Since then, RHD has spread to over 40 countries in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Oceania, and is endemic in most parts of the world.[34]

The first reported outbreak of RHD caused by RHDVa occurred in 1984 in the Jiangsu Province of the Mainland China.[9] The outbreak occurred in a group of Angora rabbits that had been imported from Germany. The cause of the disease was determined to be a small, nonenveloped RNA virus. An inactivated vaccine was developed that proved effective in preventing disease.[9] In less than a year, the disease spread over an area of 50,000 km2 in China and killed 140 million domestic rabbits.[35]

South Korea was the next country to report RHD outbreaks following the importation of rabbit fur from Mainland China.[35][36] RHD has since spread to and become endemic in many countries in Asia, including India and the Middle East.

From China, RHDVa spread westward to Europe. The first report of RHD in Europe came from in Italy in 1986.[35] From there, it spread to much of Europe. Spain's first reported case was in 1988,[35] and France, Belgium, and Scandinavia followed in 1990. Spain experienced a large die-off of wild rabbits, which in turn caused a population decline in predators that normally ate rabbits, including the Iberian lynx and Spanish imperial eagle.[37][38]

RHD caused by RHDVa was reported for the first time in the United Kingdom in 1992.[39] This initial epidemic was brought under control in the late 1990s using a combination of vaccination, strict biosecurity, and good husbandry.[15] The newer viral strain RHDV2 was first detected in England and Wales in 2014, and soon spread to Scotland and Ireland.[15]

In 2010, a new virus variant called rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus 2 (RHDV2) emerged in France.[40] RHDV2 has since spread from France to the rest of Europe, Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand. Outbreaks started occurring in the United States and Vancouver Island Canada in 2019.

RHD was detected for the first time in Finland in 2016. The outbreak occurred in feral European rabbits, and genetic testing identified the viral strain as RHDV2. Cases of viral transmission to domesticated pet rabbits have been confirmed, and vaccinating rabbits has been recommended.[41]

In 1991, a strain of the RHDVa virus, Czech CAPM 351RHDV, was imported to Australia[42] under strict quarantine conditions to research the safety and usefulness of the virus if it were used as a biological control agent against Australia and New Zealand's rabbit pest problem. Testing of the virus was undertaken on Wardang Island in Spencer Gulf off the coast of the Yorke Peninsula, South Australia. In 1995, the virus escaped quarantine and subsequently killed 10 million rabbits within 8 weeks of its release.[43] In March 2017, a new Korean strain known as RHDV K5 was successfully released in a deliberate manner after almost a decade of research. This strain was chosen in part because it functions better in cool, wet regions where the previous Calicivirus was less effective.[44]

In July 1997, after considering over 800 public submissions, the New Zealand Ministry of Health decided not to allow RHDVa to be imported into New Zealand to control rabbit populations. However, in late August, RHDVa was confirmed to have been deliberately and illegally introduced to the Cromwell area of the South Island. An unsuccessful attempt was made by New Zealand officials to control the spread of the disease. It was, however, being intentionally spread, and several farmers (notably in the Mackenzie Basin area) admitted to processing rabbits that had died from the disease in kitchen blenders for further spreading. Had the disease been introduced at a better time, control of the population would have been more effective, but it was released after breeding had commenced for the season, and rabbits under 2 weeks old at the time of the introduction were resistant to the disease. These young rabbits were, therefore, able to survive and breed rabbit numbers back up. Ten years on, rabbit populations (in the Mackenzie Basin in particular) are beginning to reach near preplague proportions once again, though they have not yet returned to pre-RHD levels.[45][46] Resistance to RHD in New Zealand rabbits has led to the widespread use of Compound 1080 (Sodium fluoroacetate). The government and department of conservation are having to increase their use of 1080 to protect reserve land from rabbits and preserve the gains made in recent years through the use of RHD.[47]

Isolated outbreaks of RHDVa in domestic rabbits have occurred in the United States, the first of which was in Iowa in 2000.[48] In 2001, outbreaks occurred in Utah, Illinois, and New York.[49][50][51] More recent outbreaks of RHDVa have occurred in 2005 in Indiana and 2018 in Pennsylvania.[52][53] Each of these outbreaks was contained and was the result of separate but indeterminable introductions of RHDVa.[10] RHDVa does not affect the native cottontail and jackrabbits in the United States, so the virus did not become endemic.[33]

The first report of RHDV2 virus in North America was on a farm in Québec, in 2016. In 2018, a larger outbreak occurred in feral European rabbits on Delta and Vancouver Island, British Columbia.[54] The disease was confirmed later that year in a pet rabbit in Ohio.[55] In July 2019, the first case of RHDV2 in Washington was confirmed in a pet rabbit from Orcas Island.[56] RHDV2 have been reported in domestic rabbits in Washington and New York.

In 2020, outbreaks of the disease in domestic rabbits, as well as cottontail rabbits and hares, have been reported in Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Texas, Nevada, California and Utah.[57] Affected wildlife include mountain cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus nutalli), desert cottontail rabbits (S. audubonii), antelope jackrabbits (L. alleni), and black-tailed jackrabbits (L. californicus).[58] The virus circulating in the Southwest United States is distinct from the RHDV2 isolated from New York, Washington, Ohio, and British Columbia, Canada.[58] The sources of these outbreaks are unknown.[58]

In June 2022, a case occurred in Hawaii. It was first confirmed in a neutered hare on Maui. Department of Agriculture inspectors began testing after becoming aware of 9 rabbit deaths on a Maui farm.[59]

Mexico experienced an outbreak of RHDVa in domestic rabbits from 1989 to 1991, presumably following the importation of rabbit meat from the People's Republic of China.[60] Strict quarantine and depopulation measures were able to eradicate the virus, and the country was officially declared to be RHD-free in 1993.[61] A second outbreak of RHD in domestic rabbits began in the state of Chihuahua in April 2020 and has since spread to Sonora, Baja California, Baja California Sur, Coahuila, and Durango.[62]

Since 1993, RHDVa has been endemic in Cuba. Four epizootics involving domesticated rabbits were reported in 1993, 1997, 2000–2001, and 2004–2005. As consequence, thousands of rabbits have died or have been slaughtered each time.[63] The virus is also believed to be thriving in Bolivia.

Rabbit Calicivirus CSIRO

Rabbit Calicivirus CSIRO Rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD), also known as viral hemorrhagic disease (VHD), is a highly infectious and lethal form of viral hepatitis that affects European rabbits. Some viral strains also affect hares and cottontail rabbits. Mortality rates generally range from 70 to 100 percent. The disease is caused by strains of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV), a lagovirus in the family Caliciviridae.

La neumonía hemorrágica vírica o enfermedad hemorrágica del conejo, es una enfermedad sumamente contagiosa tanto directamente mediante vía orofecal, o en forma indirecta mediante utensilios o a través de ropa expuesta.

La enfermedad se transmite por contacto directo, y también a través del contacto con los comederos de los conejos y por la ropa expuesta a los animales enfermos. La mayor parte de los conejos adultos enferman luego de un periodo de incubación, de 1 a 2 días. Los animales mueren en forma aguda, frecuentemente sin que se perciba ningún síntoma.

Los síntomas que pueden mostrar son fiebre, anorexia, depresión, y dificultad para respirar, abdomen distendido, diarrea y cianosis. En la fase final sangran por la nariz, y pueden presentar convulsiones, entrando en coma y muriendo por deficiencia de coagulación que produce hemorragias internas en diversos órganos.

No existe un tratamiento eficaz, ya que al manifestarse los síntomas los animales ya tienen afectados en forma grave los principales órganos y no queda tiempo para que la medicación actúe.

La neumonía hemorrágica vírica o enfermedad hemorrágica del conejo, es una enfermedad sumamente contagiosa tanto directamente mediante vía orofecal, o en forma indirecta mediante utensilios o a través de ropa expuesta.

À ne pas confondre avec la fièvre hémorragique virale chez l'homme.

La maladie hémorragique virale du lapin, provoquée par un virus de la famille des Caliciviridés, et du genre Lagovirus, est une maladie hautement contagieuse des lapins. Elle entraîne une atteinte hémorragique pulmonaire et trachéale, causant des épistaxis, d'où son nom.

Elle a été découverte pour la première fois en Chine en 1984. Elle touche la Corée en 1985 puis arrive en Europe en 1986 avec 2 foyers en Italie et en Europe de l'est. Par la suite, elle se dissémine sur une grande partie du continent et entraîne de grosses pertes chez les lapins domestiques comme chez les sauvages. Des cas ont été signalés en Afrique puis l'Australie (1995) et la Nouvelle-Zélande (1997) sont touchées par le virus.

En 2017 le gouvernement australien a décidé de répandre ce virus sur son territoire pour se débarrasser du lapin de Garenne, espèce qui ravage la biodiversité du pays. En l'espace de 2 mois, 42 % de la population de lapins de Garenne recensée dans l'État de la Nouvelle-Galles du Sud a été éliminée[1].

Les modes de contamination sont les voies orale ou respiratoire : entre lapins, par l'alimentation, les sécrétions, les excréments, l’urine et les insectes.

La maladie touche préférentiellement les animaux jeunes approchant de l'âge adulte, épargnant généralement les animaux de moins de 2 mois encore protégés par les anticorps maternels.

Le virus a un tropisme pour les cellules épithéliales du poumon, du foie, des intestins et pour les cellules lymphoïdes de la rate.

Les principales lésions macroscopiques sont un œdème du poumon, une hépatite nécrosante aigüe, ainsi que des hémorragies séreuses.

La période d'incubation dure généralement de 48 à 72 heures, avec peu de signes cliniques spécifiques : anorexie, difficultés respiratoires, saignements de nez, opisthotonos. Elle se traduit par un syndrome hémorragique généralisé et une CIVD, la mort survenant brutalement à la suite d'une thrombose des vaisseaux principaux et une atteinte sévère du foie et des poumons.

Un virus très voisin touche les populations de lièvres sauvages, sans transmission ni immunisation croisée. Plusieurs espèces dont le chien et le loup ont présenté expérimentalement une excrétion de virus dans les selles sans expression de signes cliniques pouvant constituer des porteurs sains.

Il n'existe pas de traitement efficace[réf. nécessaire], une vaccination semestrielle est généralement proposée, souvent pratiquée conjointement à la vaccination contre la myxomatose et la gastro entérite infectieuse.

En ce qui concerne les élevages, les conseils sont de :

À ne pas confondre avec la fièvre hémorragique virale chez l'homme.

La maladie hémorragique virale du lapin, provoquée par un virus de la famille des Caliciviridés, et du genre Lagovirus, est une maladie hautement contagieuse des lapins. Elle entraîne une atteinte hémorragique pulmonaire et trachéale, causant des épistaxis, d'où son nom.

Viraal hemorragisch syndroom (VHS), ook bekend onder de namen VHD (viral haemorrhagic disease) en RHD (rabbit haemorrhagic disease), is een specifieke konijnenziekte veroorzaakt door een calicivirus. Waarschijnlijk komt dit virus al langere tijd bij konijnen voor maar is het recentelijk (jaren negentig van de vorige eeuw) gemuteerd naar een dodelijke vorm. Eind 2015 werd aangetoond dat een nieuwe mutatie uit Frankrijk België en Nederland bereikte: VHS2 (of RHD2). Sedert verwijst men naar de originele variant als VHS1 (of RHD1).

Jonge konijnen tot 10 weken worden niet ziek van VHS-1, mogelijk vanwege antistoffen in de moedermelk. VHS-2 is wel dodelijk voor jongere dieren.

VHS werd voor het eerst waargenomen in China en in juni 1990 ook aangetoond in België. VHS-1 was verantwoordelijk voor een grote sterfte onder wilde konijnen. In 2004 was er nog maar 30% over van de Nederlandse konijnenpopulatie uit 1994.

Het virus ontsnapte uit een op een eiland gelegen laboratorium naar het Zuid-Australische vasteland in oktober 1995. In het Flinders Ranges National Park werd in november 1995 onder de konijnenpopulatie een sterftecijfer van 95% bereikt. Men schat dat gedurende die periode meer dan 30 miljoen konijnen in het gebied de dood vonden.[1][2]

VHS wordt verspreid door direct of indirect contact: direct van konijn op konijn door lichaamsvocht en uitwerpselen, indirect door urine besmet gras, stekende insecten of door de mens (kleding en schoeisel). Tamme konijnen worden dan vaak ook besmet door dit indirecte contact, omdat het virus tot 3 maanden kan overleven op bijvoorbeeld kleding.

De incubatietijd is 16 tot 48 uur, waarna de ziekte snel en dodelijk toeslaat. Zieke konijnen worden sloom, stil, stoppen met eten en krijgen vaak diarree. Uiteindelijk kan het konijn lijden aan neusbloedingen en inwendige longbloedingen, waardoor het gaat gillen van de pijn. Eenmaal ziek, sterft het konijn binnen één tot drie dagen (VHS1) of drie tot vijf dagen (VHS2).

Beide varianten zijn niet te behandelen, maar wel te voorkomen door vaccinatie. Wanneer in een stal een dier besmet raakt met VHS1 kan een noodvacinatie bij de andere niet ingeënte dieren erger voorkomen, bij VHS2 helpt dit niet[3] . Om besmetting te voorkomen, is ook goede hygiëne belangrijk.

Viraal hemorragisch syndroom (VHS), ook bekend onder de namen VHD (viral haemorrhagic disease) en RHD (rabbit haemorrhagic disease), is een specifieke konijnenziekte veroorzaakt door een calicivirus. Waarschijnlijk komt dit virus al langere tijd bij konijnen voor maar is het recentelijk (jaren negentig van de vorige eeuw) gemuteerd naar een dodelijke vorm. Eind 2015 werd aangetoond dat een nieuwe mutatie uit Frankrijk België en Nederland bereikte: VHS2 (of RHD2). Sedert verwijst men naar de originele variant als VHS1 (of RHD1).

Jonge konijnen tot 10 weken worden niet ziek van VHS-1, mogelijk vanwege antistoffen in de moedermelk. VHS-2 is wel dodelijk voor jongere dieren.

VHS werd voor het eerst waargenomen in China en in juni 1990 ook aangetoond in België. VHS-1 was verantwoordelijk voor een grote sterfte onder wilde konijnen. In 2004 was er nog maar 30% over van de Nederlandse konijnenpopulatie uit 1994.

Het virus ontsnapte uit een op een eiland gelegen laboratorium naar het Zuid-Australische vasteland in oktober 1995. In het Flinders Ranges National Park werd in november 1995 onder de konijnenpopulatie een sterftecijfer van 95% bereikt. Men schat dat gedurende die periode meer dan 30 miljoen konijnen in het gebied de dood vonden.

Wirusowa krwotoczna choroba królików (RHD) – choroba krwotoczna królików, wybitnie zaraźliwa, wywołana przez wirus z rodziny kaliciwirusów - viral haemorrhagic disease (VHD). Jest to wirus łatwo przenoszący się z jednego osobnika na drugiego. Może dojść do zakażenia w kontakcie bezpośrednim lub poprzez przedmioty na których znajduje się wirus. Choroba ta jest zwana potocznie krwotoczną chorobą królików lub chińskimi pomorem królików, ponieważ po raz pierwszy opisaną ją w Chinach w 1984 roku. Do Polski dotarła na przełomie 1986 i 1987.

Wirus jest bardzo odporny i w pokojowej temperaturze potrafi wytrzymać 105 dni, w temperaturze 60 °C - 2 dni, a w temperaturze 4 °C - 225 dni.

Do zakażenia może dojść u królików powyżej 2. miesiąca życia. Okres inkubacji wynosi 16-72 godzin.

Cechuje się nagłą śmiercią, która następuje w ciągu 48 godzin od zakażenia. Śmiertelność 80-100%.

Ustawa z dnia 11 marca 2004 roku o ochronie zdrowia zwierząt oraz zwalczaniu chorób zakaźnych zwierząt mówi, że pomór należy do chorób, które podlegają obowiązkowi rejestracji. Ponadto króliki chore oraz podejrzane o zakażenie należy odizolować od innych osobników oraz poddać eutanazji, a zwłoki zutylizować, ponieważ są one nadal źródłem zakażenia. Po zlikwidowaniu ogniska choroby należy przeprowadzić dezynfekcję klatek i pomieszczeń następującymi preparatami 5% roztworem formaliny lub 1-2% roztworem sody żrącej. Wymagany jest kontakt z lekarzem weterynarii.

Choroby nie można wyleczyć, dlatego stosuje się profilaktyczne szczepionki. Jedną z nich jest Cunivac działająca przez 5-7 miesięcy oraz Nobivac Myxo-RHD[1] dająca odporność na 12 miesięcy[1].

Wirusowa krwotoczna choroba królików (RHD) – choroba krwotoczna królików, wybitnie zaraźliwa, wywołana przez wirus z rodziny kaliciwirusów - viral haemorrhagic disease (VHD). Jest to wirus łatwo przenoszący się z jednego osobnika na drugiego. Może dojść do zakażenia w kontakcie bezpośrednim lub poprzez przedmioty na których znajduje się wirus. Choroba ta jest zwana potocznie krwotoczną chorobą królików lub chińskimi pomorem królików, ponieważ po raz pierwszy opisaną ją w Chinach w 1984 roku. Do Polski dotarła na przełomie 1986 i 1987.

Kaningulsot eller RVHD (efter engelskans Rabbit Viral Haemorrhagic Disease) är ett virus som infekterar europeiska kaniner. Kaningulsot upptäcktes på 1980-talet i Kina och därefter har flera utbrott runt om i världen dokumenterats och sjukdomen är numera etablerad på flertalet platser i Asien, Europa och USA. Viruset har en hög virulens och dödar värden i de flesta fall. Några av de vanligaste symptomen är förstorad lever, blödningar, kraftig viktminskning och slutligen kvävning innan dödsfall. Smittade kaniner som överlever kan utveckla antikroppar och kan på så vis inte bli smittade av viruset igen. Immunitet kan även uppnås genom moderns placenta och råmjölk. På så vis utvecklar nyfödda kaninungar immunitet mot kaningulsot i upp till 50 dagar.

Vaccin finns numera tillgängliga för att förhindra sjukdomens spridning mellan vilda och tama kaniner men utbrott sker trots detta i vissa delar av världen. Viruset har även använts som biokontroll av kaninpopulationer i Australien och Nya Zeeland där kaninen är en invasiv art och utgör hot mot de endemiska arter som finns där. Introduktionen ledde till kraftiga minskningar av kaninpopulationerna och det har därefter gjorts upprepade försök att introducera viruset till Nya Zeeland på olaglig väg.

2010 upptäcktes en ny typ av viruset, RHDV2, i Frankrike. Under 2015 konstaterades att RHDV2 finns i Sverige.[2]

Kaningulsot viruset är ett enkelsträngat Calcivirus som tillhör genuset Lagovirus. Det infekterar europeisk kanin (Oryctolagus cuniculus) och dess domesticerade släktingar. Viruspartikeln är mycket litet och den omges inte av en kapsid (proteinskal). Viruset är besläktat med det virus som ger upphov till Calciviruset European brown hare syndrome hos harar men kaningulsot kan ej infektera harar och European brown hare syndrome kan inte infektera kaniner. Dessa två virus är mycket lika när det gäller mortalitet, symptom och viruspartikelns morfologi [3]

År 1984 drabbades kaninpopulationerna i Kina av en ny virussjukdom som karaktäriserades av sin extrema dödlighet och höga smittorisk hos både domesticerade och vilda kaniner [3]. Detta var hos angorakaniner som var importerade från Tyskland [4] och på mindre än ett år dödades 140 miljoner tamkaniner i Kina. Kaningulsot beskrevs för första gången i Korea 1985 och kopplades till importering av päls från Kina [3]. Därefter spreds viruset sedan snabbt mellan tamkaniner och vilda kaniner från Asien till Europa och USA. I Europa påträffades sjukdomen för första gången i Italien 1986 [4] och spreds sedan därifrån till resten av Europa och blev endemisk i flera länder [3] Kaningulsot orsakar ekonomiska förluster i kötts- och pälsindustrin för kanin och påverkar även i sin tur predatorerna på kaninerna i det vilda [3]

Inkubationstiden för kaningulsot är 24-72 timmar. Det finns tre olika kliniska grader av sjukdomen: Preakut, akut och mild. Preakut innebär att den infekterade kaninen dör inom några timmar utan att uppvisa tidigare symptom. När sjukdomen är av den akuta graden uppstår en variation av symptom så som plötslig depression, kraftig viktminskning och apati. Även blödningar i ögon, blod och avföring kan uppstå. Koagulationssjukdomar, anemi och leukocytos kan också tillhöra symptomen. Ofta dör kaninen efter en kort period med krampanfall och tecken på kvävning. Precis innan dödsfall kan kroppstemperaturen höjas och plötsliga skrik kan uppstå. Vid milda fall tillfrisknar kaninen spontant och utvecklar därför antikroppar. En infekterad kanin som dött av kaningulsot hittas ofta med sina ben utsträckta kippandes efter andan [3]. Vid en obduktion kan en kraftigt förstorad lever ses på grund av att virusreplikation av kaningulsotvirus sker där [5].

Kaningulsot smittas främst via direktkontakt med smittade eller döda djur, exempelvis oralt, nasalt eller via ögon. Exkretionsprodukter såsom urin, avföring och respiratoriska utsöndringar tros även kunna innehålla virus. Döda djur kan förbli smittsamma i upp till en månad. Det är även möjligt att djur kan smittas via mat, vatten eller sina bon. Flugor och andra djur kan fungera som smittbärare för viruset och oftast behövs det bara ett fåtal viruspartiklar för att infektera kaninen [3]. Kaningulsot har även setts i exkretionsprodukter hos asätare och predatorer men skadar troligtvis inte djuret då virusreplikation inte kan ske i dessa organismer [6]

Mortaliteten av kaningulsot är relativt svår att beräkna då många kaniner dör i sina hålor. Man har även sett att fångsten av kaniner för att bedöma kaningulsot kan stressa djuren och därmed öka mortaliteten av andra anledningar än kaningulsot. Mortaliteten i en smittad population varierar med klimatet och är högre i torra och varma områden än i fuktiga kalla regioner [3]. Kaniner som överlever smittan utvecklar specifika antikroppar mot viruset och blir immuna. Upptäckten av specifika antikroppar i serum från friska kaniner och harar i områden där utbrott av sjukdomen inte har skett visar att viruset har en stor utbredning. 17-20 % av friska kaniner rapporterades innehålla naturliga antikroppar mot kaningulsotvirus [4]. Ett annat sätt att uppnå immunitet är via placentan och modersmjölken. De antikroppar som överförs genom placentan (moderkaka) avtar sedan med ökad ålder och kroppsvikt [3]. När kaninungarna dricker modersmjölken överförs immunitet vilket gör att ungarna är skyddade mot viruset i minst 50 dagar [4]. Vanligtvis föds kaninungarna vid tidig vår och det är då vanligt med utbrott av kaningulsot under sen vår eller tidig sommar då de maternella antikropparna avtagit [7]

Det finns flera olika metoder för att upptäcka kaningulsotvirus så som HA (Hemagglutination assay), HI (Hemagglutination inhibiton assay) och ELISA (enzymkopplad immunadsorberande analys), elektronmikroskop och RT-PCR. RT-PCR som benämns realtids-PCR är oftast den bästa metoden då den kan undersöka ett stort antal prover och kartlägga epidemiologin.

De första vaccin som utvecklades mot kaningulsot var vävnadsvacciner som producerats från levern hos kaniner. Detta vaccin utvecklades i Kina, Ungern, Bulgarien och Spanien för att råda bot på sjukdomen och resulterade i att dödsfall kunde förhindras bara 5-6 dagar efter vaccination. 1990 blev ett inaktiverat vaccin (ARVILAP) tillgängligt i Tyskland där kaningulsot är en anmälningsskyldig sjukdom sedan samma årtal. För att kontrollera sjukdomen så dödades och förintades alla sjuka och döda infekterade djur medan alla friska djur i både infekterade och icke infekterade flockar vaccinerades [8] [9] . Idag vaccineras våra tamkaniner med vaccinet Nobivax Myxo-RHD som är ett kombinerat vaccin för kaningulsot och myxomatos [10] [11]

I Australien och Nya Zeeland där kaniner är en invasiv art och ett hot mot det endemiska vilda floran och faunan introducerades kaningulsotvirus för en biokontroll av kaniner 1991 [6] I Australien hölls importerade kaniner med kaningulsotvirus i karantän för att kunna kartlägga viruset, dock lyckades smittan ändå sprida sig vidare ut i Australien. Det blev ett hårt slag för de kaninpopulationer som fanns i Australien och kaningulsotvirus visade sig vara en mycket kraftfull biokontrollsmetod mot de tidigare importerade kaninerna [3] . I Nya Zeeland gjordes sedan återupprepade försök att införa viruset för att kunna reglera kaninpopulationerna, detta dock på olaglig väg [12] .

Statens veterinärmedicinska anstalt om Kaningulsot (Rabbit hemorrhagic disease, RHD).

Kaningulsot eller RVHD (efter engelskans Rabbit Viral Haemorrhagic Disease) är ett virus som infekterar europeiska kaniner. Kaningulsot upptäcktes på 1980-talet i Kina och därefter har flera utbrott runt om i världen dokumenterats och sjukdomen är numera etablerad på flertalet platser i Asien, Europa och USA. Viruset har en hög virulens och dödar värden i de flesta fall. Några av de vanligaste symptomen är förstorad lever, blödningar, kraftig viktminskning och slutligen kvävning innan dödsfall. Smittade kaniner som överlever kan utveckla antikroppar och kan på så vis inte bli smittade av viruset igen. Immunitet kan även uppnås genom moderns placenta och råmjölk. På så vis utvecklar nyfödda kaninungar immunitet mot kaningulsot i upp till 50 dagar.

Vaccin finns numera tillgängliga för att förhindra sjukdomens spridning mellan vilda och tama kaniner men utbrott sker trots detta i vissa delar av världen. Viruset har även använts som biokontroll av kaninpopulationer i Australien och Nya Zeeland där kaninen är en invasiv art och utgör hot mot de endemiska arter som finns där. Introduktionen ledde till kraftiga minskningar av kaninpopulationerna och det har därefter gjorts upprepade försök att introducera viruset till Nya Zeeland på olaglig väg.

2010 upptäcktes en ny typ av viruset, RHDV2, i Frankrike. Under 2015 konstaterades att RHDV2 finns i Sverige.

兎ウイルス性出血病(うさぎウイルスせいしゅっけつびょう、英: rabbit viral hemorrhagic disease)とは兎出血病ウイルス感染を原因とする兎の感染症。日本では家畜伝染病予防法において届出伝染病に指定されており、対象動物は兎。国際獣疫事務局においてリストB疾病に指定されている。兎出血病ウイルスはカリシウイルス科ラゴウイルス属に属するRNAウイルス。接触伝播あるいは節足動物による機械的伝播により感染が成立する。致死率は高く、発熱、元気消失、食欲廃絶、神経症状などを示し、数日で死亡するが、症状を示すことなく突然死する場合もある。全身の諸臓器において出血が認められる。不活化ワクチンが開発されているが、日本では実用化されていない。

国際獣疫事務局(OIE) - 国際連合食糧農業機関(FAO) - 農林水産省/農業・食品産業技術総合研究機構/動物衛生研究所 - 検疫所/家畜防疫官 - 家畜保健衛生所/家畜防疫員/獣医師 - 日本家畜商協会/家畜商 - 屠畜場/化製場 - 保健所 - 農業共済組合/農業災害補償制度

炭疽症 - オーエスキー病 - ブルータング - ブルセラ症 - クリミア・コンゴ出血熱 - エキノコックス症 - 口蹄疫 - 心水病 - 日本脳炎 - レプトスピラ症 - 新世界ラセンウジバエ - 旧世界ラセンウジバエ - ヨーネ病 - Q熱 - 狂犬病 - リフトバレー熱 - 牛疫 - 旋毛虫症 - 野兎病 - 水胞性口炎 - 西ナイル熱

アナプラズマ病 - バベシア症 - 牛疫 - 牛海綿状脳症 - 結核 - 牛ウイルス性下痢 - 牛肺疫 - 牛白血病 - 出血性敗血症 - 牛伝染性鼻気管炎 - 皮膚病 - 悪性カタル熱 - タイレリア症 - トリコモナス病 - ナガナ病

山羊関節炎・脳脊髄炎 - 伝染性無乳症 - 山羊伝染性胸膜肺炎 - 流行性羊流産 - 羊慢性進行性肺炎 - ナイロビ羊病 - 緬羊ブルセラオビス - 小反芻獣疫 - サルモネラ症 - スクレイピー - 羊痘/山羊痘

アフリカ馬疫 - 馬伝染性子宮炎 - 媾疫 - 東部馬脳炎 - 西部馬脳炎 - 馬伝染性貧血 - 馬インフルエンザ - 馬ピロプラズマ病 - 馬鼻肺炎 - 馬ウイルス性動脈炎 - 鼻疽 - スーラ病 - ベネズエラ馬脳脊髄炎

クラミジア - 鶏伝染性気管支炎 - 鶏伝染性喉頭気管炎 - 鶏マイコプラズマ病 - あひる肝炎 - 家禽コレラ - 家禽チフス - 鳥インフルエンザ - 伝染性ファブリキウス囊病 - マレック病 - ニューカッスル病 - ひな白痢 - 七面鳥鼻気管炎

伝染性造血器壊死症 - 伝染性造血器壊死症 - コイ春ウイルス病 - ウイルス性出血性敗血症 - 伝染性膵臓壊死症 - 伝染性サケ貧血 - 流行性潰瘍症候群 - 細菌性腎臓病 - ギロダクチルス症 - マダイイリドウイルス病

Bonamia ostreae感染症 - Bonamia exitiosus感染症 - Marteilia refringens感染症 - Mikrocytos roughleyi感染症 - Perkinsus marinus感染症 - Perkinsus olseni感染症 - Xenohaliotis californiensis感染症

牛疫 - 牛肺疫 - 口蹄疫 - 日本脳炎 - 狂犬病 - 水胞性口炎 - リフトバレー熱 - 炭疽症 - 出血性敗血症 - ブルセラ症 - 結核病 - ヨーネ病 - ピロプラズマ症 - アナプラズマ病 - 牛海綿状脳症 - 鼻疽 - 馬伝染性貧血 - アフリカ馬疫 - 豚コレラ - アフリカ豚コレラ - 豚水胞病 - 家きんコレラ - 高病原性鳥インフルエンザ - ニューカッスル病 - 家きんサルモネラ感染症 - 腐蛆病

ブルータング - アカバネ病 - 悪性カタル熱 - チュウザン病 - ランピースキン病 - 牛ウイルス性下痢・粘膜病 - 牛伝染性鼻気管炎 - 牛白血病 - アイノウイルス感染症 - イバラキ病 - 牛丘疹性口炎 - 牛流行熱 - 類鼻疽 - 破傷風 - 気腫疽 - レプトスピラ症 - サルモネラ症 - 牛カンピロバクター症 - トリパノソーマ病 - トリコモナス病 - ネオスポラ症 - 牛バエ幼虫症 - ニパウイルス感染症 - 馬インフルエンザ - 馬ウイルス性動脈炎 - 馬鼻肺炎 - 馬モルビリウイルス肺炎 - 馬痘 - 野兎病 - 馬伝染性子宮炎 - 馬パラチフス - 仮性皮疽 - 小反芻獣疫 - 伝染性膿疱性皮膚炎 - ナイロビ羊病 - 羊痘 - マエディ・ビスナ - 伝染性無乳症 - 流行性羊流産 - トキソプラズマ病 - 疥癬 - 山羊痘 - 山羊関節炎・脳脊髄炎 - 山羊伝染性胸膜肺炎 - オーエスキー病 - 伝染性胃腸炎 - 豚エンテロウイルス性脳脊髄炎 - 豚繁殖・呼吸障害症候群 - 豚水疱疹 - 豚流行性下痢 - 萎縮性鼻炎 - 豚丹毒 - 豚赤痢 - 鳥インフルエンザ - 鶏痘 - マレック病 - 伝染性気管支炎 - 伝染性喉頭気管炎 - 伝染性ファブリキウス嚢病 - 鶏白血病 - 鶏結核病 - 鶏マイコプラズマ病 - ロイコチトゾーン病 - あひる肝炎 - あひるウイルス性腸炎 - 兎ウイルス性出血病 - 兎粘液腫 - バロア病 - チョーク病 - アカリンダニ症 - ノゼマ病

兎ウイルス性出血病(うさぎウイルスせいしゅっけつびょう、英: rabbit viral hemorrhagic disease)とは兎出血病ウイルス感染を原因とする兎の感染症。日本では家畜伝染病予防法において届出伝染病に指定されており、対象動物は兎。国際獣疫事務局においてリストB疾病に指定されている。兎出血病ウイルスはカリシウイルス科ラゴウイルス属に属するRNAウイルス。接触伝播あるいは節足動物による機械的伝播により感染が成立する。致死率は高く、発熱、元気消失、食欲廃絶、神経症状などを示し、数日で死亡するが、症状を示すことなく突然死する場合もある。全身の諸臓器において出血が認められる。不活化ワクチンが開発されているが、日本では実用化されていない。