en

names in breadcrumbs

This species is harmless to human interests and values.

Wood Turtles had a more southerly distribution during the Late Pleistocene ("ice age"), with fossils being described from Tennessee and Georgia (Ernst, Lovich, and Barbour, 1994).

The oldest fossil Wood Turtle appears to be a nearly complete shell of an adult male specimen found in late Hemphillian deposits (late Miocene epoch) in Nebraska. This fossil, which is approximately 6 million year old, will be described by its discoverer, Mr. Shane Tucker, and Dr. Michael Voorhies of the University of Nebraska (Voorhies, pers. comm., June 2000).

The relationships of the Wood Turtle to its relatives in the subfamily emydinae (in the genera Clemmys, Emys, Emydoidea, and Terrapene) have been recently studied; the genus Clemmys, as long suspected, was found to be paraphyletic (Bickham et al., 1996; Burke et al., 1996; Feldman and Parham, 2001). According to the latest published revisions, the Wood Turtle will now be combined with its closest relative, the Bog turtle (Clemmys muhlenbergii), in the genus Glyptemys; the correct scientific names for these turtles are now Glyptemys insculpta and Glyptemys muhlenbergii, respectively, although it will predictably take some time before the new combinations are universally used and recognized. The Spotted Turtle, Clemmys guttata, is the only species remaining in the genus Clemmys (Holman and Fritz, 2001; Feldman and Parham, 2002).

Hybrids between the Wood Turtle and the Blanding's turtle, Emydoidea blandingii, have recently been described (Harding, 1999).

Glyptemys insculpta displays a number of life history traits that make it especially vulnerable to exploitation and habitat alteration by humans. In this and many other turtle and tortoise species, low reproductive rates (low clutch size and/or high nest and hatchling mortality) and delayed sexual maturity are normally balanced by relatively high survivorship of older juveniles and adults, and a long adult reproductive lifespan. It has been demonstrated that such species have virtually no harvestable surplus in their populations (assuming the desirability of population stability), and any factor (natural or human-caused) which reduces the normally high survivorship of older juveniles and mature adults will result in a declining or even extirpated population. In addition, these turtle populations will predictably be very slow in recovering from any factor which significantly reduces numbers of mature individuals. The Wood Turtle may be equally, or even more vulnerable than certain other well-studied turtle species (such as Emydoidea blandingii) in this regard (Congdon et al., 1993; Harding, 1991, and unpubl. data).

Direct removal by humans is the primary threat to the species in some portions of the Wood Turtle's range. Removal can take the form of road mortality, shooting of basking turtles by vandals, commercial poaching for the pet trade, or just incidental collection by stream-based recreationists such as canoeists and fishermen. In one study (Garber and Burger, 1995), a previously unexploited population of Wood Turtles declined to virtual extirpation within a decade of being exposed to human recreationists. Glyptemys insculpta is legally protected from commercial collecting practically range-wide at present, and collection for personal use is at least regulated, if not prohibited, by most of the states and provinces where it occurs.

Wood Turtles have also suffered greatly from habitat loss and degradation. While the species seems somewhat tolerant of modest timber harvest and agricultural activity in its habitat, intensive forestry, farming, or industrial or residential development in the riparian zone can severely impact Wood Turtles. Intensive, mechanized agriculture can result in maiming and deaths of Wood Turtles due to impacts from farm machinery (Saumure and Bider, 1998). Certain fish management practices that involve removal ("stabilization") of sand bank nesting sites along northern rivers is a relatively recent threat that can reduce reproductive opportunities for this and other turtle species. An additional threat is the recent increase in numbers of "human-subsidized" predators, particularly raccoons (Procyon lotor), which not only destroy turtle eggs and hatchlings, but can also kill or maim adult turtles (Harding, 1985; 1991, 1997, pers.obs.).

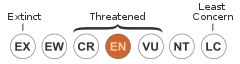

The long-term future for this species is bleak unless its riparian habitats are protected and the animals themselves are left undisturbed. Wood turtles are listed as vulnerable by the IUCN and special concern in the state of Michigan, and they are in CITES appendix II.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: appendix ii

State of Michigan List: special concern

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: vulnerable

Wood Turtles were once harvested extensively for human food (in the east) and for the biological supply trade (especially in the western Great Lakes area), and in the last few decades they have been mercilessly exploited for the pet trade range-wide. None of these activities are sustainable in the long-term; most populations of Wood Turtles are now greatly reduced from former numbers, and many have been totally extirpated (Harding, 1991, 1997).

Positive Impacts: pet trade ; food ; body parts are source of valuable material; research and education

Glyptemys insculpta is an omnivorous species that can feed both in or out of water. Natural foods reported for the species include leaves and flowers of various herbaceous and woody plants (violet, strawberry, raspberry, willow), fruits (berries), fungi, slugs, snails, worms, and insects. They are usually slow, deliberate feeders, and seem incapable of capturing fish or other fast-moving prey, though they will opportunistically consume young mice or eggs, or scavenge dead animals (Ernst, Lovich, and Barbour, 1994; Harding, 1997)

Wood Turtles in some populations are known to capture earthworms by thumping the ground with their forefeet or the front of the plastron. It is thought that the worms may mistake the vibrations caused by this thumping for the approach of a mole or perhaps the advent of a hard rain, and thus come to the surface, only to be grabbed by the hungry turtle (Harding and Bloomer, 1979; Kaufmann, et al., 1989; Ernst, Lovich, and Barbour, 1994).

Animal Foods: eggs; carrion ; insects; terrestrial non-insect arthropods; mollusks; terrestrial worms; aquatic crustaceans

Plant Foods: leaves; roots and tubers; fruit; flowers

Other Foods: fungus

Primary Diet: omnivore

Glyptemys insculpta occurs in a relatively small area of eastern Canada and the northeastern United States, from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick south through New England, Pennsylvania and northern New Jersey, to northern Virginia, and west through southern Quebec, southern Ontario, northern Michigan (northern Lower and Upper Peninsulas), northern and central Wisconsin, to eastern Minnesota; an isolated population occurs in northeastern Iowa. Within this range, this turtle is generally uncommon to rare and spottily distributed (Harding, 1997; Conant and Collins, 1998).

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

Glyptemys insculpta is almost invariably found in association with moving water (streams, creeks, or rivers), although individuals in some populations may wander considerable distances away from water, especially in the warmer months. Females may be more terrestrial than males in some populations. Streams with sand or sand and gravel bottoms are preferred, but rocky stream courses are sometimes used, especially in the north-eastern portion of the range. Wood turtles are often described as a woodland species, but in some places they appear to thrive in a mosaic habitat of riparian woods, shrub or berry thickets, swamps, and open, grassy areas. Some unvegetated or sparsely vegetated patches, preferably with moist, but not saturated, sand substrate, are needed for nesting (Harding, 1991; Ernst, Lovich, and Barbour, 1994; Harding, 1997; Tuttle, 1996).

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial ; freshwater

Terrestrial Biomes: forest

Aquatic Biomes: rivers and streams

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 58 (high) hours.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 12.5 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 60.0 years.

Adult wood turtles have a carapace length of 16 to 25 cm (6.3 to 9.8 inches). The brownish to gray-brown carapace has a low central keel, and the scutes usually show well-defined concentric growth annuli, giving the shell a rough, "sculptured" appearance that probably gave the species its specific name (and perhaps its common name as well). In some specimens, the accumulated annuli may give each carapace scute a somewhat flattened pyramidal shape (though this character has been over-emphasized in some earlier literature). The carapaces of older specimens may be worn quite smooth. The vertebral scutes sometimes display radiating yellow streaks, or yellow pigment may be restricted to the keel. The hingeless plastron is yellow with a black blotch at the rear outer corner of each scute; there is a V-shaped notch at the tail. Plastral scutes display prominent annuli, though, as with the carapace, these can be worn smooth over time.

(Note: Counting the scute annuli, or "growth rings," can offer a reasonable estimate of age in a juvenile animal, but this method becomes increasingly unreliable as the specimen approaches and then attains maturity. In older animals, growth, and thus the formation of annuli, may essentially cease; however, counting scute annuli will usually provide a reliable minimum age for a specimen.)

The head of the Wood Turtle is black, occasionally with light dots or other markings; the scales on the upper legs are black to mottled brown, while the skin on the throat, lower neck, and on the lower surfaces of the legs can be yellow, orange, or orange-red to salmon-red, sometimes speckled with darker pigment. This skin color varies between localities, and shows some regional variation, with yellow to yellow-orange predominating in the western (Great Lakes) part of the range, and orange to reddish skin color characterizing eastern specimens (Harding, 1997).

Hatchling Wood Turtles have nearly circular carapaces that range in length from 2.8 to 3.8 cm (1.1 to 1.5 inches); their tails are nearly as long as the carapace. At hatching they are a uniform brown or gray color dorsally; the brighter juvenile and adult coloration described above is attained during the first full year of growth (Harding, 1997).

Compared to females, adult male G. insculpta tend to have wider heads and higher, more elongate and domed, carapaces; the plastron is concave (depressed) in the center, and their tails are thicker and longer, with the vent (cloacal opening) beyond the edge of the carapace when the tail is extended. Compared to males, adult females tend to have lower and wider, more flaring carapaces; the plastron is flat to slightly convex, the tail is narrower and slightly shorter, with the vent situated beneath the edge of the carapace when the tail is extended (Ernst, Lovich, and Barbour, 1994; Harding, 1997).

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Male wood turtles form dominance hierarchies in the wild, and will often aggressively attack other males; females also exhibit aggressive behavior, which can be directed both toward males and other females. Older, larger males tend to be dominant over smaller individuals, and also have better success in fertilizing eggs (Kaufmann, 1992).

Courtship may include a mating "dance" in which the male and female face each other and swing their heads back and forth; perhaps more frequently the male simply pursues the female while nipping at her limbs and shell and then mounts her carapace. While thus positioned, the male may nip at the female's head and often thumps the female's carapace by straightening and then flexing his front limbs, and dropping his plastron onto the female's shell. Copulation usually occurs in shallow water on a sloping stream bank, though courtship may be initiated on land. Mating may occur at any time during the active season, but is probably most frequent in spring and fall, when the turtles are more aquatic.

In May or June, female wood turtles seek open, sunny nesting sites, preferring sandy banks adjacent to moving water whenever possible. The female excavates the nest with her hind feet, creating a globular cavity about 5 to 13 cm (2 to 5 inches) deep. Clutch size ranges from 3 to 18 eggs (usually 5 to 13). The eggs are carefully buried, and the females goes to considerable effort to smooth and obscure the nest site, but then departs, offering no further care to her offspring. Only one clutch is produced each year, and females may not reproduce every year (Harding, 1977, 1991, 1997).

Most wood turtle eggs never hatch; nest predation by raccoons, skunks, shrews, foxes, and other predators can typically result in high losses, sometimes approaching the entire year's reproductive effort for a turtle population when predator numbers are high. In a Michigan study, 70 to 100 percent of nests were typically lost each year, mostly to raccoons. For eggs fortunate enough to escape detection, incubation requires from 47 to 69 days, dependent mostly on temperature and moisture conditions in the nest. Hatchling G. insculpta generally emerge from their nests in late August or September and move to water. They appear not to overwinter in the nest, as occurs in some other freshwater turtle species (Ernst, Lovich, and Barbour, 1994; Harding, 1997: Tuttle, 1996).

In this species, the sex of the hatchling is independent of incubation temperature, a departure from the trend in closely related emydid species (such as Clemmys guttata and Emydoidea blandingii) in which embryonic sex differentiation is directly related to nest temperatures during the middle third of the incubation period (Ewert and Nelson, 1991).

Wood turtles in the wild usually reach sexual maturity between 14 and 20 years of age; in a Michigan study, most reproductive adults were in their third and fourth decade of life. Maximum lifespan in the wild is unknown, but can probably exceed the age of 58 obtained by a captive specimen (Ernst, Lovich, and Barbour, 1994; Harding 1991, 1997).

Key Reproductive Features: gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 5840 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 5840 days.

Ar vaot-koad (Glyptemys insculpta, bet Clemmys insculpta) a zo ur stlejvil hag a vev e Norzhamerika.

Ar vaot-koad (Glyptemys insculpta, bet Clemmys insculpta) a zo ur stlejvil hag a vev e Norzhamerika.

La tortuga de bosc (Glyptemys insculpta) és una espècie de tortuga de la família dels emídids (Emydidae) endèmica d'Amèrica del Nord. Comparteix el gènere Glyptemys només amb una altra espècie: la Glyptemys muhlenbergii. La closca de la tortuga de bosc arriba a mesurar entre 14 i 20 cm, i es caracteritza pels patrons piramidals de la seva part superior. Morfològicament és similar a la Glyptemys muhlenbergii, la Clemmys guttata, i la Emys blandingii. la tortuga de bosc es troba en una àmplia àrea des de Nova Escòcia, fins a Minnesota per l'oest i Virgínia al sud. En èpoques de glaceres va haver de desplaçar-se cap al sud i s'han trobat restes dels seus esquelets tan llunyans com a Geòrgia.

Passa gran part del seu temps als voltants de l'aigua, i prefereix els rierols clars amb fons sorrencs i poc profunds. Com indica el seu nom també es pot trobar a aquest tortuga d'estany en els boscos i herbassars, encara que rarament s'allunya més d'uns centenars de metres de l'aigua. És una espècie diürna i no es mostra clarament territorial. Passa l'hivern en hibernació i també estiven en els períodes més calorosos de l'estiu.

La tortuga de bosc és omnívora i pot alimentar-se tant a terra com en l'aigua. Com a mitjana aquesta tortuga es desplaça uns 108 m diaris. Els humans són la seva principal amenaça i provoquen un gran nombre de morts en destruir els seus hàbitats, en atropellaments de trànsit i durant les tasques agrícoles, i també es redueixen les seves poblacions pel col·leccionisme il·legal. La tortuga de bosc pot arribar a viure 40 anys en la naturalesa i 58 en captivitat.

La tortuga de bosc (Glyptemys insculpta) és una espècie de tortuga de la família dels emídids (Emydidae) endèmica d'Amèrica del Nord. Comparteix el gènere Glyptemys només amb una altra espècie: la Glyptemys muhlenbergii. La closca de la tortuga de bosc arriba a mesurar entre 14 i 20 cm, i es caracteritza pels patrons piramidals de la seva part superior. Morfològicament és similar a la Glyptemys muhlenbergii, la Clemmys guttata, i la Emys blandingii. la tortuga de bosc es troba en una àmplia àrea des de Nova Escòcia, fins a Minnesota per l'oest i Virgínia al sud. En èpoques de glaceres va haver de desplaçar-se cap al sud i s'han trobat restes dels seus esquelets tan llunyans com a Geòrgia.

Passa gran part del seu temps als voltants de l'aigua, i prefereix els rierols clars amb fons sorrencs i poc profunds. Com indica el seu nom també es pot trobar a aquest tortuga d'estany en els boscos i herbassars, encara que rarament s'allunya més d'uns centenars de metres de l'aigua. És una espècie diürna i no es mostra clarament territorial. Passa l'hivern en hibernació i també estiven en els períodes més calorosos de l'estiu.

La tortuga de bosc és omnívora i pot alimentar-se tant a terra com en l'aigua. Com a mitjana aquesta tortuga es desplaça uns 108 m diaris. Els humans són la seva principal amenaça i provoquen un gran nombre de morts en destruir els seus hàbitats, en atropellaments de trànsit i durant les tasques agrícoles, i també es redueixen les seves poblacions pel col·leccionisme il·legal. La tortuga de bosc pot arribar a viure 40 anys en la naturalesa i 58 en captivitat.

Die im Osten Nordamerikas lebende Waldbachschildkröte (Glyptemys insculpta, Syn.: Clemmys insculpta) ist eine Art der Neuwelt-Sumpfschildkröten. Bis vor wenigen Jahren wurde sie wie die Moorschildkröte noch zur Gattung Clemmys zugerechnet, die heute als monogenerische Gattung nur noch die Tropfenschildkröte enthält.[1]

Die Waldbachschildkröte ernährt sich von Beeren und Obst sowie animalischer Kost und überwintert gewöhnlich im Bodenschlamm eines Gewässers. Die Tiere haben einen ausgeprägten Orientierungssinn und zeigen eine für Kriechtiere ungewöhnliche Aktivität bei niedrigen Temperaturen (sie wurde schon im Schnee angetroffen).

Die Waldbachschildkröte wirkt sehr robust. Sie besitzt einen flachen, längs-ovalen Rückenpanzer der im hinteren Bereich etwas breiter wird. Die hinteren Randschilder sind gesägt. Sie besitzt einen ausgeprägten Mittelkiel und die namensgebenden Wachstumsringe (lat. insculpta ‚gemeißelt‘) der einzelnen Rückenpanzerschilder sind sehr ausgeprägt. Der Rückenpanzer kann grün-grau, hellbraun bis dunkelbraun gefärbt sein. Oft ist eine schwarze oder gelbliche Strahlenzeichnung zu erkennen. Das Plastron (Bauchpanzer) ist von gelblicher Farbe. Jedes Schild besitzt einen dunklen Fleck jeweils an der unteren, äußeren Ecke. Der Oberkiefer ist vorne eingekerbt. Der Kopf kann gräulich bis schwarz gefärbt, der Hals gelblich bis rötlichbraun. Die Beine besitzen kräftige Krallen, die Schwimmhäute sind schwach ausgeprägt.

Die Männchen werden bis zu 13 cm, Weibchen bis zu 23 cm groß und 600–1000 Gramm schwer. Die Männchen dieser Art werden in der Regel kleiner als die Weibchen. Letztere besitzen einen längeren, an der Basis dickeren Schwanz als die Weibchen. Der Bauchpanzer der Männchen ist konkav nach innen gewölbt, derjenige der Weibchen gerade oder konvex. Leicht nach außen. Die Männchen haben sehr massige Köpfe.

Glyptemys insculpta ist im Nordosten Nordamerikas beheimatet. Ihr Verbreitungsgebiet reicht vom Süden Kanadas (Neuschottland) bis etwa nach Virginia und gegen Westen um die großen Seen bis nach Wisconsin. Ihr Lebensraum sind Kleingewässer in Laub- und Mischwäldern sowie Seen, Teiche, Bäche, Flüsse, Sümpfe und Feuchtwiesen. Die Waldbachschildkröte ist nicht sehr eng an Gewässer gebunden. Sie halten sich häufig an Land auf und unternehmen weite Wanderungen.

Sie fressen sowohl Pflanzen und Früchte als auch Regenwürmer, Aas, Gehäuse- und Nacktschnecken sowie Insekten und Kaulquappen. Sie überwintern in verrottenden Laubhaufen, Erdlöchern, Höhlen unter Uferböschungen oder im Uferschlamm von Gewässern.

Während der Fortpflanzungszeit zeigen sie ein ausgeprägtes Balzverhalten. Männchen sind in dieser Zeit häufig sehr aggressiv gegeneinander. Die Weibchen legen ihre Gelege normalerweise zwischen Mai und Juni. Gelege umfassen zwischen vier und zwölf Eier, die elliptisch geformt sind. Im Norden des Verbreitungsgebietes schlüpfen die Jungen gelegentlich erst im nächsten Jahr und überwintern damit in den Eiern. Auch eine Überwinterung in den Nistgruben kommt vor.

Die im Osten Nordamerikas lebende Waldbachschildkröte (Glyptemys insculpta, Syn.: Clemmys insculpta) ist eine Art der Neuwelt-Sumpfschildkröten. Bis vor wenigen Jahren wurde sie wie die Moorschildkröte noch zur Gattung Clemmys zugerechnet, die heute als monogenerische Gattung nur noch die Tropfenschildkröte enthält.

Die Waldbachschildkröte ernährt sich von Beeren und Obst sowie animalischer Kost und überwintert gewöhnlich im Bodenschlamm eines Gewässers. Die Tiere haben einen ausgeprägten Orientierungssinn und zeigen eine für Kriechtiere ungewöhnliche Aktivität bei niedrigen Temperaturen (sie wurde schon im Schnee angetroffen).

The wood turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) is a species of turtle endemic to North America. It is in the genus Glyptemys, a genus which contains only one other species of turtle: the bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii). The wood turtle reaches a straight carapace length of 14 to 20 centimeters (5.5 to 7.9 in), its defining characteristic being the pyramidal shape of the scutes on its upper shell. Morphologically, it is similar to the bog turtle, spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata), and Blanding's turtle (Emydoidea blandingii). The wood turtle exists in a broad geographic range extending from Nova Scotia in the north (and east) to Minnesota in the west and Virginia in the south. In the past, it was forced south by encroaching glaciers: skeletal remains have been found as far south as Georgia.

It spends a great deal of time in or near the water of wide rivers, preferring shallow, clear streams with compacted and sandy bottoms. The wood turtle can also be found in forests and grasslands, but will rarely be seen more than several hundred meters from flowing water. It is diurnal and is not overtly territorial. It spends the winter in hibernation and the hottest parts of the summer in estivation.

The wood turtle is omnivorous and is capable of eating on land or in water. On an average day, a wood turtle will move 108 meters (354 ft), a decidedly long distance for a turtle. Many other animals that live in its habitat pose a threat to it. Raccoons are over-abundant in many places and are a direct threat to all life stages of this species. Inadvertently, humans cause many deaths through habitat destruction, road traffic, farming accidents, and illegal collection. When unharmed, it can live for up to 40 years in the wild and 58 years in captivity.

The wood turtle belongs to the family Emydidae. The specific name, insculpta, refers to the rough, sculptured surface of the carapace. This turtle species inhabits aquatic and terrestrial areas of North America, primarily the northeast of the United States and parts of Canada.[5] Wood turtle populations are under high conservation concerns due to human interference of natural habitats. Habitat destruction and fragmentation can negatively impact the ability for wood turtles to search for suitable mates and build high quality nests.

Formerly in the genus Clemmys, the wood turtle is now a member of the genus Glyptemys, a classification that the wood turtle shares with only the bog turtle.[6] It and the bog turtle have a similar genetic makeup, which is marginally different from that of the spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata), the only current member of the genus Clemmys.[7] The wood turtle has undergone extensive scientific name changes by various scientists over the course of its history.[6] Today, there are several prominent common names for the wood turtle, including sculptured tortoise, red-legged tortoise, and redleg.[6]

Although no subspecies are recognized, there are morphological differences in wood turtles between areas. Individuals found in the west of its geographic range (areas like the Great Lakes and the Midwest United States) have a paler complexion on the inside of the legs and underside of the neck than ones found in the east (places including the Appalachian Mountains, New York, and Pennsylvania).[8] Genetic analysis has also revealed that southern populations have less genetic diversity than the northern; however, both exhibit a fair amount of diversity considering the decline in numbers that have occurred during previous ice ages.[9]

Wood turtles grow to between 14 and 20 centimeters (5.5 and 7.9 in) in straight carapace length,[10] and reach a maximum of 23.4 centimeters (9.2 in).[6][8] They have a rough carapace that is a tan, grayish brown or brown color, with a central ridge (called a keel) made up of a pyramidal pattern of ridges and grooves.[10] Older turtles typically display an abraded or worn carapace. Fully grown, they weigh 1 kilogram (35 oz).[11] The wood turtle's karyotype consists of 50 chromosomes.[8]

The larger scutes display a pattern of black or yellow lines. The wood turtle's plastron (ventral shell) is yellowish in color[10] and has dark patches. The posterior margin of the plastron terminates in a V-shaped notch.[6] Although sometimes speckled with yellowish spots, the upper surface of the head is often a dark gray to solid black. The ventral surfaces of the neck, chin, and legs are orange to red with faint yellow stripes along the lower jaw of some individuals.[6] Seasonal variation in color vibrancy is known to occur.[8]

At maturity, males, who reach a maximum straight carapace length of 23.4 centimeters (9.2 in), are larger than females, who have been recorded to reach 20.4 centimeters (8.0 in).[8] Males also have larger claws, a larger head, a concave plastron, a more dome-like carapace, and longer tails than females.[12] The plastron of females and juveniles is flat while in males it gains concavity with age.[11] The posterior marginal scutes of females and juveniles (of either sex) radiate outward more than in mature males.[12] The coloration on the neck, chin, and inner legs is more vibrant in males than in females who display a pale yellowish color in those areas.[8] Hatchlings range in size from 2.8 to 3.8 centimeters (1.1 to 1.5 in) in length (straight carapace measurement).[12] The plastrons of hatchlings are dull gray to brown. Their tail usually equals the length of the carapace and their neck and legs lack the bright coloration found in adults.[10] Hatchlings' carapaces also are as wide as they are long and lack the pyramidal pattern found in older turtles.[12]

The eastern box turtle (Terrapene c. carolina) and Blanding's turtle are similar in appearance to the wood turtle and all three live in overlapping habitats. However, unlike the wood turtle, both Blanding's turtle and the eastern box turtle have hinged plastrons that allow them to completely close their shells. The diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) has a shell closely resembling the wood turtle's; however its skin is gray in color, and it inhabits coastal brackish and saltwater marshes.[10] The bog turtle and spotted turtle are also similar, but neither of these has the specific sculptured surface found on the carapaces of the wood turtle.[13]

The wood turtle is found in most New England states, Nova Scotia, west to Michigan, northern Indiana and Minnesota,[8] and south to Virginia. Overall, the distribution is disjunct with populations often being small and isolated. Roughly 30% of its total population is in Canada.[11] It prefers slow-moving streams containing a sandy bottom and heavily vegetated banks. The soft bottoms and muddy shores of these streams are ideal for overwintering. Also, the areas bordering the streams (usually with open canopies[4] ) are used for nesting. Spring to summer is spent in open areas including forests, fields, bogs, wet meadows, and beaver ponds. The rest of the year is spent in the aforementioned waterways.[10]

The densities of wood turtle populations have also been studied. In the northern portion of its range (Quebec and other areas of Canada), populations are fairly dilute, containing an average of 0.44 individuals per 1 hectare (2.5 acres), while in the south, over the same area, the densities varied largely from 6 to 90 turtles. In addition to this, it has been found that colonies often have more females than males.[7]

In the western portion of its range, wood turtles are more aquatic.[14] In the east, wood turtles are decidedly more terrestrial, especially during the summer. During this time, they can be found in wooded areas with wide open canopies. However, even here, they are never far from water and will enter it every few days.[15]

In the past, wood turtle populations were forced south by extending glaciers. Remains from the Rancholabrean period (300,000 to 11,000 years ago) have been found in states such as Georgia and Tennessee, both of which are well south of their current range.[8] After the receding of the ice, wood turtle colonies were able to re-inhabit their customary northern range[16] (areas like New Brunswick and Nova Scotia).[8]

This species is oviparous, meaning these turtles produce offspring by laying eggs only and do not provide parental care outside of nest-building. Thus, the location and quality of nesting sites determine the offspring survival and fitness, so females invest significant time and energy into nest site selection and construction. Females select nest sites based on soil temperature (preferring warmer temperature nest sites), but not soil composition.[17] Average nest size is four inches wide and three inches deep. Also, females build nests in elevated areas in order to avoid flooding and predation. After laying eggs, female wood turtles will cover the nest with leaves or dirt in order to hide the unhatched eggs from predators, and then the female leaves the nest location until the next mating season. Nesting sites can be used by the same female for multiple years.[5] Because nest building occurs along rivers, females tend to spend more time along river areas, compared to male turtles.[18]

During the spring, the wood turtle is active during the daytime (usually from about 7:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m.)[15] and will almost always be found within several hundred metres of a stream. The early morning and late afternoon are preferred foraging periods.[15] Throughout this season, the wood turtle uses logs, sandy shores, or banks to bask in sunlight.[19] In order to maintain its body temperatures through thermoregulation, it spends a considerable amount of time basking, most of which takes place in the late morning and late afternoon. The wood turtle reaches a peak body temperature of 37 °C (99 °F) after basking. During times of extreme heat, it has been known to estivate. Several reports mention individuals resting under vegetation, fallen debris and in shallow puddles. During the summer, the wood turtle is considered a largely terrestrial animal.[4] At night, its average body temperature drops to between 15 and 20 °C (59 and 68 °F)[20] and it will rest in small creeks or nearby land (usually in areas containing some sort of underbrush or grass).[15]

During warmer weather, the wood turtle stays in the water for a larger percentage of the time.[20] For this reason, during the winter months (and the late fall and early spring) it is considered an aquatic turtle.[4] November through February or March is spent in hibernation at the bottom of a small, flowing river. The wood turtle may hibernate alone or in large groups. During this period, individuals bury themselves in the thick mud at the bottom of the river and rarely move. During hibernation, it is vulnerable to flash floods. Emergence does not occur until March or sometimes April, months that mark the beginning of its activation period (males are typically more active than females at this time).[20]

Males are known to be aggressive, with larger and older turtles being more dominant. Larger males rank higher on the social hierarchy often created by wood turtle colonies. In the wild, the submissive turtle is either forced to flee, or is bombarded with physical abuses, which include biting, shoving, and ramming. Larger and more dominant males will sometimes try to remove a subordinate male while he is mating with a female. The defender will, if he does not successfully fight for his position, lose the female to the larger male. Therefore, among males, there is a direct relationship between copulation opportunities and social rank.[21] However, the outcome of encounters between two turtles is more aggression-dependent than size-dependent. The wood turtle that is more protective of his or her area is the victor. Physical bouts between wood turtles (regardless of sex) increases marginally during the fall and spring (times of mating).[22]

The wood turtle is omnivorous, feeding mainly on plant matter and animals both on land and in water. It eats prey such as beetles, millipedes, and slugs. Also, wood turtles consume specific fungi (Amanita muscaria and Leccinum arcolatum), mosses, grasses, various insects, and also carrion.[23] On occasion, it can be seen stomping the ground with alternating hits of the left and right front feet. This behavior imitates the vibrations caused by moles, sometimes causing earthworms to rise to the surface where they quickly become easy prey.[24] When hunting, the wood turtle pokes its head into such areas as dead and decaying logs, the bottoms of bushes, and in other vegetation. In the water, it exhibits similar behavior, searching algae beds and cavities along the sides of the stream or river.[23]

Many different animals are predators of or otherwise pose a threat to the wood turtle. They include snapping turtles, raccoons, otters, foxes, and cats. All of these species destroy unhatched eggs and prey upon hatchlings and juveniles. Several animals that often target wood turtle eggs are the common raven and coyote, which may completely destroy the nests they encounter. Evidence of predatory attacks (wounds to the skin and such) are common on individuals, but the northern populations tend to display more scarring than the southern ones. In addition to these threats, wood turtles also suffer from leech infestations.[25]

The wood turtle can travel at a relatively fast speed (upwards of 0.32 kilometers per hour (0.20 mph)); it also travels long distances during the months that it is active. In one instance, of nine turtles studied, the average distance covered in a 24-hour period was 108 meters (354 ft), with a net displacement of 60 meters (197 ft).[26]

The wood turtle, an intelligent animal, has homing capabilities. Its mental capacity for directional movement was discovered after the completion of an experiment that involved an individual finding food in a maze. The results proved that these turtles have locating abilities similar to that of a rat. This was also proved by another, separate experiment. One male wood turtle was displaced 2.4 kilometers (1.5 mi) after being captured, and within five weeks, it returned to the original location. The homing ability of the wood turtle does not vary among sexes, age groups, or directions of travel.[22]

The wood turtle takes a long time to reach sexual maturity, has a low fecundity (ability to reproduce), but has a high adult survival rate. However, the high survival rates are not true of juveniles or hatchlings. Although males establish hierarchies, they are not territorial.[4] The wood turtle becomes sexually mature between 14 and 18 years of age. Mating activity among wood turtles peaks in the spring and again in the fall, although it is known to mate throughout the portion of the year they are active. However, it has been observed mating in December.[27] In one rare instance, a female wood turtle hybridized with a male Blanding's turtle.[28]

The courtship ritual consists of several hours of 'dancing,' which usually occurs on the edge of a small stream. Males often initiate this behavior: starting by nudging the females shell, head, tail, and legs. Because of this behavior, the female may flee from the area, in which case the male will follow.[27] After the chase (if it occurs), the male and female approach and back away from each other as they continually raise and extend their heads. After some time, they lower their heads and swing them from left to right.[19] Once it is certain that the two individuals will mate, the male will gently bite the female's head and mount her. Intercourse lasts between 22 and 33 minutes.[27] Actual copulation takes place in the water,[19] between depths between 0.1 and 1.2 meters (0 and 4 ft). Although unusual, copulation does occur on land.[27] During the two prominent times of mating (spring and fall), females are mounted anywhere from one to eight times, with several of these causing impregnation. For this reason, a number of wood turtle clutches have been found to have hatchlings from more than one male.[21]

Nesting occurs from May until July. Nesting areas receive ample sunlight, contain soft soil, are free from flooding, and are devoid of rocks and disruptively large vegetation.[21] These sites however, can be limited among wood turtle colonies, forcing females to travel long distances in search of a suitable site, sometimes a 250 meters (820 ft) trip. Before laying her eggs, the female may prepare several false nests.[28] After a proper area is found, she will dig out a small cavity, lay about seven eggs[19] (but anywhere from three to 20 is common), and fill in the area with earth. Oval and white, the eggs average 3.7 centimeters (1.5 in) in length and 2.36 centimeters (0.93 in) in width, and weigh about 12.7 grams (0.45 oz). The nests themselves are 5 to 10 centimeters (2.0 to 3.9 in) deep, and digging and filling it may take a total of four hours. Hatchlings emerge from the nest between August and October with overwintering being rare although entirely possible. An average length of 3.65 centimeters (1.44 in), the hatchlings lack the vibrant coloration of the adults.[28] Female wood turtles in general lay one clutch per year and tend to congregate around optimal nesting areas.[19]

The wood turtle, throughout the first years of its life, is a rapid grower. Five years after hatching, it already measures 11.5 centimeters (4.5 in), at age 16, it is a full 16.5 to 17 centimeters (6.5 to 6.7 in), depending on sex. The wood turtle can be expected to live for 40 years in the wild, with captives living up to 58 years.[23]

The wood turtle is the only known turtle species in existence that has been observed committing same-sex intercourse.[29] Same-sex behavior in tortoises is known in more than one species.

The wood turtle exhibits genetic sex determination, in contrast to the temperature-dependent sex determination of most turtles.[30]

Specific mating courtship occurs more often in the Fall months and usually during the afternoon hours from 11:00 to 13:00 when many of the turtles are out in the population feeding.[31] Mating is based on a male competitive hierarchy where a few higher ranked males gain the majority of mates in the population. Male wood turtles fight to gain access to female mates. These fights involve aggressive behaviors such as biting or chasing one another, and the males defend themselves by retreating their heads into their hard shells. The higher ranked winning males in the hierarchy system have a greater number of offspring than the lower ranked male individuals, increasing the dominant male's fitness.[32] Female wood turtles mate with multiple males and are able to store sperm from multiple mates.[32] Although the mechanism of sperm storage is unknown for the Wood Turtle species, other turtle species have internal compartments that can store viable sperm for years. Multiple mating ensures fertilization of all the female's eggs and often results in multiple paternity of a clutch, which is a common phenomenon exhibited by many marine and freshwater turtles.[32] Multiple paternity patterns have been made evident in wood turtle populations by DNA fingerprinting. DNA fingerprinting of turtles involves using an oligonucleotide probe to produce sex specific markers, ultimately providing multi-locus DNA markers.[33]

Despite many sightings and a seemingly large and diverse distribution, wood turtle numbers are in decline. Many deaths caused by humans result from: habitat destruction, farming accidents, and road traffic. Also, it is commonly collected illegally for the international pet trade. These combined threats have caused many areas where they live to enact laws protecting it.[7] Despite legislation, enforcement of the laws and education of the public regarding the species are minimal.[34]

For proper protection of the wood turtle, in-depth land surveys of its habitat to establish population numbers are needed.[35] One emerging solution to the highway mortality problem, which primarily affects nesting females,[14] is the construction of under-road channels. These tunnels allow the wood turtle to pass under the road, a solution that helps prevent accidental deaths.[7] Brochures and other media that warn people to avoid keeping the wood turtle as a pet are currently being distributed.[35] Next, leaving nests undisturbed, especially common nesting sites and populations, is the best solution to enable the wood turtle's survival.[36]

While considered nationally as threatened by COSEWIC, the wood turtle is listed as vulnerable within the province of Nova Scotia under the Species at Risk Act. The species is highly susceptible to human land use activities, and special management practices for woodlands, rivers and farmland areas as well as motor vehicle use restrictions and general disruption protection during critical times such as nesting and movement to overwintering habitat is closely monitored.[37] Since 2012, the Clean Annapolis River Project (CARP) has provided research and stewardship for this species including the identification of crucial habitats, distribution and movement estimation, and outreach.[38]

The wood turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) is a species of turtle endemic to North America. It is in the genus Glyptemys, a genus which contains only one other species of turtle: the bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii). The wood turtle reaches a straight carapace length of 14 to 20 centimeters (5.5 to 7.9 in), its defining characteristic being the pyramidal shape of the scutes on its upper shell. Morphologically, it is similar to the bog turtle, spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata), and Blanding's turtle (Emydoidea blandingii). The wood turtle exists in a broad geographic range extending from Nova Scotia in the north (and east) to Minnesota in the west and Virginia in the south. In the past, it was forced south by encroaching glaciers: skeletal remains have been found as far south as Georgia.

It spends a great deal of time in or near the water of wide rivers, preferring shallow, clear streams with compacted and sandy bottoms. The wood turtle can also be found in forests and grasslands, but will rarely be seen more than several hundred meters from flowing water. It is diurnal and is not overtly territorial. It spends the winter in hibernation and the hottest parts of the summer in estivation.

The wood turtle is omnivorous and is capable of eating on land or in water. On an average day, a wood turtle will move 108 meters (354 ft), a decidedly long distance for a turtle. Many other animals that live in its habitat pose a threat to it. Raccoons are over-abundant in many places and are a direct threat to all life stages of this species. Inadvertently, humans cause many deaths through habitat destruction, road traffic, farming accidents, and illegal collection. When unharmed, it can live for up to 40 years in the wild and 58 years in captivity.

The wood turtle belongs to the family Emydidae. The specific name, insculpta, refers to the rough, sculptured surface of the carapace. This turtle species inhabits aquatic and terrestrial areas of North America, primarily the northeast of the United States and parts of Canada. Wood turtle populations are under high conservation concerns due to human interference of natural habitats. Habitat destruction and fragmentation can negatively impact the ability for wood turtles to search for suitable mates and build high quality nests.

El galápago de bosque (Glyptemys insculpta) es una especie de tortuga de la familia Emydidae endémica de Norteamérica. Comparte el género Glyptemys solo con otra especie: el galápago de Muhlenberg. El caparazón del galápago de bosque llega a medir entre 14 y 20 cm, y se caracteriza por los patrones piramidales de su parte superior. Morfológicamente es similar al galápago de Muhlenberg, la tortuga moteada, y la tortuga de Blanding. El galápago de bosque se encuentra en un amplio área desde Nueva Escocia, hasta Minnesota por el oeste y Virginia en el sur. En épocas glaciares tuvo que desplazarse hacia el sur y se han encontrado restos de sus esqueletos tan lejos como en Georgia.

Pasa gran parte de su tiempo en las inmediaciones del agua, y prefiere los arroyos claros con fondos arenosos y poco profundos. Como indica su nombre también se puede encontrar a este galápago en los bosques y herbazales, aunque raramente se aleja más de unos cientos de metros del agua. Es una especie diurna y no se muestra claramente territorial. Pasa el invierno en hibernación y también se aletarga en los periodos más calurosos del verano.

El galápago de bosque es omnívoro y puede alimentarse tanto en tierra como en el agua. Como media este galápago se desplaza unos 108 m diarios. Los humanos son su principal amenaza y provocan un gran número de muertes al destruir sus hábitats, en atropellos de tráfico y durante las labores agrícolas, y también se reducen sus poblaciones por el coleccionismo ilegal. El galápago de bosque puede llegar a vivir 40 años en la naturaleza y 58 en cautividad.

Anteriormente situada en el género Clemmys, el galápago de bosque actualmente es uno de los dos miembros del género Glyptemys, junto al galápago de Muhlenberg.[3] Ambas están cercanamente emparentadas con la tortuga moteada, el único miembro actual del género Clemmys.[4] El galápago de bosque ha sufrido muchos cambios en su nombre, tanto el científico como el común, a lo largo de la historia.[3]

Aunque no llegan a reconocerse subespecies hay algunas diferencias morfológicas en los galápagos según las zonas. Los individuos encontrados en el oeste de su área de distribución (como los Grandes lagos y el Medio Oeste) presentan una coloración más pálida en la cara interior de sus patas y la parte inferior del cuello que las encontradas en el este (como en los Apalaches, Nueva York y Pensilvania).[5] Además los análisis genéticos han revelado que las poblaciones del sur tienen menos diversidad genética que las del norte, aunque ambas muestran una diversidad considerable teniendo en cuenta el descenso de población que sufrió durante las glaciaciones.[6]

Las tortugas de bosque crecen hasta alcanzar entre 14 y 20 cm de longitud,[7] y llegan a un máximo de 23,4 cm.[3][5] Tienen caparazones duros de color pardo o pardo grisáceo, con una protuberancia longitudinal en su parte central formada por patrones piramidales de crestas y surcos.[7] Los galápagos más viejos presentan los caparazones rozados y desgastados. Cuando están completamente desarrollados pesan alrededor de un 1 kg.[8] El cariotipo de la tortuga de bosque está compuesto por 50 cromosomas.[5]

Las placas más grandes muestran patrones con líneas negras o amarillas. El plastrón (caparazón ventral) es de color amarillento con manchas oscuras.[7] El borde trasero del plastrón tiene una muesca en forma de uve.[3] La parte superior de la cabeza es de color gris oscuro o negro liso, aunque algunas veces presenta motas amarillenta. La parte inferior del cuello, la barbilla y las patas son de color anaranjado a rojo, con tenues franjas amarillas a lo largo de la mandíbula inferior de algunos individuos.[3] Se producen una variación estacional de la intensidad de su color.[5]

Los machos adultos son más grandes que las hembras, alcanzando máximos de 23,4 cm y 20,4 cm respectivamente.[5] Además los machos tienen garras y cabeza son más grandes, su plastrón es cóncavo, y la parte superior de su caparazón es más pronunciada, y su cola es más larga que la de las hembras.[9] El plastrón de las hembras y los juveniles es plano, y en los machos se va haciendo cóncavo con la edad.[8] Las placas de los bordes posteriores de las hembras y juveniles (de ambos géneros) sobresalen más que las de los machos adultos.[9] La coloración del cuello, la barbilla y el interior de las patas es más intensa en los en los machos que en las hembras que presentan estas zonas de color amarillento pálido.[5] El caparazón de los recién nacidos mide entre 2,8 y 3,8 cm.[9] El plastrón de los recién nacidos presenta una coloración que va del gris pálido al pardo. Generalmente la longitud de sus colas iguala la longitud de su caparazón y el color de su cuello y patas carece de la intensa coloración de los adultos.[7] Los caparazones de los recién nacidos es tan ancho como largo y carece del patrón piramidal de los galápagos adultos.[9]

La tortuga caja oriental y la tortuga de Blanding son de aspecto similar al galápago de bosque y las tres viven en hábitats que se superponen. Sin embargo a diferencia de la tortuga de bosque, la tortuga de Blanding y los miembros de la familia de las tortugas caja tienen plastrones articulados que les permiten cerrar completamente sus conchas. La tortuga espalda de diamante tiene un caparazón que se parece bastante al del galápago de bosque, sin embargo su piel es de color gris y vive en marismas salobres y saladas.[7] También se parece al galápago de Muhlenberg y la tortuga moteada, pero ninguno de los dos presenta el patrón de placas piramidal del galápago de bosque.[10]

El galápago de bosque se encuentra en la mayoría de los estados de Nueva Inglaterra, Nueva Escocia, hasta Míchigan y Minnesota por el oeste,[5] y Virginia por el sur. Globalmente, la distribución es discontinua en poblaciones normalmente pequeñas y aisladas. Aproximadamente, un 30% de su población total se encuentra en Canadá.[8] Prefiere corrientes lentas que contengan un fondo de arena y bancos de vegetación densa. Los fondos suaves y las orillas fangosas de estas corrientes son ideales para pasar el invierno. Además utilizan para anidar las áreas que rodean a las corrientes (generalmente en canopias abiertas).[2] Desde la primavera hasta el verano habita en zonas abiertas incluyendo bosques, campos, pantanos, prados húmedos y estanques. El resto del año se encuentra en los cursos de agua antes mencionados.

La densidad de población del galápago de bosque ha sido estudiada. En las zonas norte (Quebec y otras áreas de Canadá), las poblaciones están bastante dispersas, conteniendo una media de 0,44 individuos por 1 hectárea, mientras que en el sur, bajo una misma zona, la densidad varía en gran parte entre 6 y 90 galápagos. Además, se ha descubierto que las colonias normalmente contienen más hembras que machos.[4]

En la parte oeste de su área de distribución, el galápago de bosque es más acuático.[11] En el este el galápago permanece más tiempo en los medios terrestres, especialmente en verano, precisamente durante esa época, se pueden encontrar en zonas arboladas con amplias canopias. De todos modos, incluso aquí, nunca se alejan demasiado del agua, y volverán a esta cada pocos días.[12]

En el pasado las poblaciones de galápago de bosque se vieron forzadas a desplazarse hacia el sur al extenderse los glaciares. Se han encontrado restos suyos del Pleistoceno (entre 300.000 y 11.000 años) en estados como Georgia y Tennessee, ambos muy al sur de su actual área de distribución.[5] Tras la retirada de los hielos, las poblaciones de galápago de bosque recolonizaron sus antiguos territorios,[13] (como Nuevo Brunswick y Nueva Escocia).[5]

El galápago de bosque durante la primavera está activo todo el día (generalmente desde las 7:00 a.m. a las 7:00 p.m.)[12] y se encontrarán siempre en las inmediaciones de los arroyos. Sus periodos de alimentación preferidos son los amaneceres y los atardeceres.[12] Durante toda esta estación los galápagos de bosque usan los troncos caídos y las orillas y los bancos de arena para calentarse al sol.[14] Pasa una considerable cantidad de tiempo al sol para regular su temperatura corporal, principalmente al mediodía y el inicio de la tarde. Tras calentarse al sol galápago de bosque alcanza una temperatura de 37 °C. Por la noche su media de temperatura corporal cae hasta temperaturas entre 15 y 20 °C,[15] mientras descansa en pequeños arroyos o la tierra circundante (generalmente en zonas que tengan algunos arbustos o hierba).[12]Durante los periodos de calor extremo se aletargan en estivación. Hay varios informes de individuos que descansan bajo la vegetación, la hojarasca o en charcos poco profundos. Durante el verano la tortuga de bosque pasa a ser un animal principalmente terrestre.[2]

Durante las épocas más frías la tortuga se queda en el agua la mayor parte del tiempo.[15] Por lo que durante este periodo (los meses del invierno, finales del otoño y comienzos de la primavera) se la considera principalmente una tortuga acuática.[2] De noviembre a febrero o marzo hiberna en el fondo de los arroyos. Durante este periodo se entierran en el barro del fondo de corrientes de agua y raramente se mueven. Durante este periodo de hibernación son vulnerables a las inundaciones repentinas. No emergen hasta marzo y algunas veces hasta abril, meses que marcan el comienzo de su periodo activo, estando en este inicio más activos los machos.[15]

Los machos son agresivos, y los más grandes y viejos suelen ser los más dominantes. Los grandes machos están en lo alto de la jerarquía social de los galápagos de bosque. En la naturaleza los galápagos de menor rango son obligados a huir mediante mordiscos, empujones y embestidas. Los machos dominantes a veces intentan apartar a los de menor rango incluso cuando se están apareando con una hembra. Por ello entre los machos hay una relación directa entre las oportunidades de cópula y el rango social.[16] Sin embargo el resultado de las peleas entre dos galápagos es más dependiente de la agresividad que del tamaño. El galápago que protege más su territorio suele ser el vencedor. Las luchas entre galápagos de bosque (con independencia del género) se incrementan ligeramente durante el otoño y la primavera (los periodos de apareamiento).[17]

El galápago de bosque es omnívoro, se alimenta principalmente de materias vegetales y de animales que atrapa tanto en tierra como en el agua. Captura presas como escarabajos, milpiés y babosas. Además los galápagos de bosque consumen algunos hongos (como (Amanita muscaria y Leccinum arcolatum), musgos, hierba, insectos variados y también carroña.[18] En ocasiones se les observa golpeando el suelo con ambas patas alternativamente. Se cree que este comportamiento imita el sonido de la lluvia cayendo y puede provocar que las lombrices de tierra salgan a la superficie y puedan ser capturadas.[14] Cuando caza asoma la cabeza entre los arbustos, los troncos podridos y entre otros tipos de vegetación. En el agua muestra un comportamiento similar buscando entre el lecho de algas o las cavidades de los márgenes de los ríos.[18]

Muchos animales son depredadores o suponen una amenaza para la tortuga de bosque. Entre ellos se encuentran las tortugas mordedoras, los puercoespines, los castores, los mapaches, las nutrias, los zorros y los gatos. Todas estas especies destruyen las puestas de huevos y cazan a los recién nacidos y juveniles. Varios animales que a menudo buscan huevos de galápago, como el cuervo y el coyote pueden llegar a destruir por completo los nidos que encuentren. Son comunes marchas de ataques de depredadores, como heridas en la piel y caparazón, tendiendo a presentar más cicatrices las poblaciones del norte que las del sur. Además de estas amenazas, los galápagos de bosque también pueden ser parasitados por las sanguijuela.[19]

El galápago de bosque puede desplazarse a una velocidad relativamente alta (superiores a 0,32 km/h) y se trasladan a largas distancias durante los meses en el que están activas. En un estudio realizado sobre nueve tortugas se estimó que se mueven una media de 108 m cada 24 horas, con una distancia global en línea recta de 60 m.[20]

Los galápagos de bosque son muy hábiles para orientarse. Se ha descubierto su gran capacidad mental para el movimiento direccional por medio de un experimento en el que se requería que un individuo encontrara comida en un laberinto. Los resultados probaron que estos galápagos tenían capacidades de localización similares a las de las ratas. En otro experimento independiente se demostró esta capacidad al observar que un galápago macho se desplazó 2,4 km después de haber sido capturado, y tras cinco semanas consiguió volver a su localización original. La capacidad de orientación de los galápagos de bosque no varía entre géneros, grupos de edad, o según la dirección del desplazamiento.[17]

Los galápagos de agua tardan mucho en alcanzar la madurez sexual, tienen una baja tasa de reproducción, aunque tienen altas tasas de supervivencia de los adultos. Aunque las tasas de supervivencia de los recién nacidos y los juveniles no son alta. Aunque los machos establecen jerarquías no son territoriales.[2] Los galápagos de bosque alcanzan la madurez sexual entre los 14 y 18 años. Los apareamientos tienen su apogeo en primavera y de otra vez en otoño, aunque se sabe que se producen a lo largo de todo el periodo en el que se encuentran activos. Ocasionalmente se han observado apareamientos en diciembre.[21] Se ha registrado un caso en el que una hembra de galápago de bosque hibridó con un macho de tortuga de Blanding.[22]

El ritual de cortejo dura varias horas y generalmente se realiza en las orillas de los arroyos. El macho a menudo lo inicia golpeando con el codo el caparazón, la cabeza, la cola y las patas de la hembra. La respuesta de la hembra a este comportamiento puede ser huir de la zona, en cuyo caso el macho la seguirá.[21] Tras la persecución (si se produce) el macho y la hembra se aproximan y se separan continuamente alzando y extendiendo sus cabezas. Después de un tiempo bajan sus cabezas y las balancean de izquierda a derecha.[14] Una vez que los dos individuos están preparados para el apareamiento, el macho muerde suavemente la cabeza de la hembra y la monta. La cópula dura entre 22 y 33 minutos.[21] La cópula propiamente dicha suele tener lugar en el agua,[14] en profundidades de entre 0,1 y 1,2 m. Aunque con menos frecuencia también se puede producir en tierra.[21] Durante los dos periodos principales de apareamiento (primavera y otoño) las hembras son entre una a ocho veces, hasta que se queden preñadas. Se ha descubierto que la puesta de una sola hembra pueden tener hijos de más de un macho.[16]

Los anidamientos se producen de mayo a julio. Las zonas de anidamiento se sitúan al sol, en suelos blandos evitando las rocas y la vegetación abundante que moleste, y al resguardo de las inundaciones.[16] La existencia de estos lugares limita las colonias de galápagos de bosque, y a veces las hembras tienen que desplazarse hasta 250 m para encontrar un sitio adecuado. Las hembras de galápago de bosque en general hacen una puesta al año y suenen congregarse alrededor de las áreas óptimas de anidamiento.[14]Antes de poner sus huevos, las hembras pueden preparar varios nidos falsos.[22] Tras encontrar una zona adecuada escavará una pequeña cavidad donde pone unos siete huevos,[14] aunque pueden poner de tres a veinte, y vuelve a taparlos con tierra. Los huevos son blancos y ovales y miden una media de 3,7 cm de largo y 2,36 cm de ancho, y pesan 12,7 g. Los nidos tienen una profundidad de 5 a 10 cm, y cavarlos y rellenarlos de nuevo puede llevarles un total de cuatro horas. La eclosión de los recién nacidos se produce entre agosto y octubre, raramente apareciendo en invierno. Los recién nacidos miden una media de 3,65 cm y carecen de los colores llamativos de los adultos.[22]

Los galápagos de bosque crecen muy rápidamente durante su primer año de vida. A los cinco años ya miden una media de 11,5 cm, y a los 16 años, alcanzan su tamaño total, de entre 16,5 y 17 cm dependiendo del sexo. La esperanza de vida del galápago de bosque en la naturaleza es de 40 años, mientras que los individuos que viven en cautividad llegan a hasta los 58 años.[18]

A pesar de los muchos avistamientos y su extensa y diversa área de distribución el galápago de bosque está en declive y sus poblaciones están muy fragmentadas. Se producen un gran número de muertes a causa de los humanos a consecuencia de: la destrucción del hábitat, los accidentes en la agricultura y por el tráfico rodado. Además son capturados ilegalmente para el tráfico de mascotas. Debido a todas estas amenazas combinadas muchas de las zonas donde viven están protegidas por ley.[4] A pesar de la legislación, su aplicación y la educación del público respecto a esta especie es escasa.[23]

Para una adecuada protección del galápago de bosque sería necesario realizar censos exhaustivos en sus hábitats, para establecer exactamente el tamaño de su población.[24] Una solución que se está empezando a poner en práctica para evitar la alta mortalidad por atropello en las carreteras, que afecta principalmente a las hembras que van a anidar,[11] es la construcción de ecoductos bajo las carreteras. Estos túneles permiten a los galápagos rebasar las carreteras sin morir atropellados.[4] Actualmente se distribuyen folletos y otros medios para advertir a la gente de que no tenga a estos galápagos como mascotas.[24] Conservar los sitios de anidamiento y evitar las molestias en ellos, especialmente de las poblaciones comunes, es la mejor solución para asegurar la supervivencia del galápago de bosque.[25]

|coautores= (ayuda)

El galápago de bosque (Glyptemys insculpta) es una especie de tortuga de la familia Emydidae endémica de Norteamérica. Comparte el género Glyptemys solo con otra especie: el galápago de Muhlenberg. El caparazón del galápago de bosque llega a medir entre 14 y 20 cm, y se caracteriza por los patrones piramidales de su parte superior. Morfológicamente es similar al galápago de Muhlenberg, la tortuga moteada, y la tortuga de Blanding. El galápago de bosque se encuentra en un amplio área desde Nueva Escocia, hasta Minnesota por el oeste y Virginia en el sur. En épocas glaciares tuvo que desplazarse hacia el sur y se han encontrado restos de sus esqueletos tan lejos como en Georgia.

Pasa gran parte de su tiempo en las inmediaciones del agua, y prefiere los arroyos claros con fondos arenosos y poco profundos. Como indica su nombre también se puede encontrar a este galápago en los bosques y herbazales, aunque raramente se aleja más de unos cientos de metros del agua. Es una especie diurna y no se muestra claramente territorial. Pasa el invierno en hibernación y también se aletarga en los periodos más calurosos del verano.

El galápago de bosque es omnívoro y puede alimentarse tanto en tierra como en el agua. Como media este galápago se desplaza unos 108 m diarios. Los humanos son su principal amenaza y provocan un gran número de muertes al destruir sus hábitats, en atropellos de tráfico y durante las labores agrícolas, y también se reducen sus poblaciones por el coleccionismo ilegal. El galápago de bosque puede llegar a vivir 40 años en la naturaleza y 58 en cautividad.

Glyptemys insculpta Glyptemys generoko animalia da. Narrastien barruko Emydidae familian sailkatuta dago.

Glyptemys insculpta Glyptemys generoko animalia da. Narrastien barruko Emydidae familian sailkatuta dago.

Metsäkilpikonna (Glyptemys insculpta syn. Clemmys insculpta) on kilpikonnalaji. Niitä on kerätty luonnosta koe-eläimiksi ja lemmikeiksi; nykyisin laji on eritäin uhanalainen.[2][1] Lajia esiintyy Yhdysvalloissa ja Kanadassa [1]ja se vaatii lauhkeaa, suunnilleen Keski-Euroopan kaltaista ilmastoa. Koiraitten suurin koko on 13cm ja naaraiden 23cm.lähde?

Metsäkilpikonnan kilvessä on selvästi erottuvat luulevyt; niiden vuosirenkaista voi karkeasti laskea kasvuikäisen konnan iän 15-20 vuoteen asti.[3]

Metsäkilpikonna (Glyptemys insculpta syn. Clemmys insculpta) on kilpikonnalaji. Niitä on kerätty luonnosta koe-eläimiksi ja lemmikeiksi; nykyisin laji on eritäin uhanalainen. Lajia esiintyy Yhdysvalloissa ja Kanadassa ja se vaatii lauhkeaa, suunnilleen Keski-Euroopan kaltaista ilmastoa. Koiraitten suurin koko on 13cm ja naaraiden 23cm.lähde?

Metsäkilpikonnan kilvessä on selvästi erottuvat luulevyt; niiden vuosirenkaista voi karkeasti laskea kasvuikäisen konnan iän 15-20 vuoteen asti.

Glyptemys insculpta

Glyptemys insculpta, la Tortue des bois, est une espèce de tortue de la famille des Emydidae[1], endémique de l'Amérique du Nord. Sa carapace peut atteindre de 14 à 20 cm de long et présente des motifs pyramidaux en relief sur le dessus. Son allure générale est assez semblable à celle de sa cousine la Tortue de Muhlenberg (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) − seule autre membre du genre Glyptemys − ainsi qu'aux proches Clemmys guttata et Emys blandingii.

Cette tortue se rencontre dans une vaste zone couvrant le nord-est de l'Amérique du Nord, allant de la Nouvelle-Écosse au Minnesota d'est en ouest et jusqu'en Virginie au sud. Par le passé sa répartition était beaucoup plus décalée vers le sud à cause des glaciations recouvrant le nord du continent, et des squelettes ont été retrouvés jusqu'en Géorgie. Ce reptile passe la plupart de son temps dans ou près de rivières larges et peu profondes, préférant les eaux claires et les fonds de sable. Il se rencontre également dans les forêts et prairies mais rarement loin d'une eau courante. C'est un animal diurne peu ou pas territorial qui hiberne l'hiver et estive durant les périodes les plus chaudes de l'été.

La Tortue des bois est omnivore et se nourrit à la fois de proies terrestres et aquatiques. Elle peut parcourir en moyenne 108 m par jour ce qui est une assez bonne performance pour une tortue. Elle est la proie potentielle de plusieurs animaux dans son aire de répartition, comme les raton-laveurs très abondants dans cette zone. Les humains sont également responsables de nombreux décès par la destruction de leur habitat, les morts liées aux véhicules, la collecte illégale et la destruction accidentelle par les activités agricoles. En dehors de ces menaces elle peut vivre jusqu'à 40 ans dans la nature et près de 60 ans en captivité.

La Tortue des bois atteint de 14 à 20 cm de long[2] pour un maximum de 23,4 cm[3],[4]. Sa carapace est rugueuse et de couleur brun-grisâtre, beige ou brun, et sa partie supérieure consiste en un motif pyramidal de creux et de nervures[2], les spécimens les plus âgés présentant généralement une carapace usée et érodée. Adultes elles peuvent peser jusqu'à 1 kg[5].

Les plus grandes scutelles présentent des lignes noires ou jaunes. Le plastron (la partie ventrale de la carapace) est jaunâtre[2] avec des taches noires, la partie postérieure se terminant par une marque en forme de « V »[3]. La peau visible sur la partie ventrale, le cou, les pattes et la queue est de couleur orange à rouge avec parfois des lignes plus pâles au niveau de la mâchoire[3]. La peau visible au-dessus est généralement gris sombre à noir bien qu'il existe des individus présentant des points jaunes. Ces couleurs peuvent varier en éclat selon les saisons[4].

Une fois matures les mâles atteignent 23,4 cm et sont plus larges que les femelles, ces dernières atteignant en général 20,4 cm[4]. Les mâles ont également de plus grandes griffes, une tête plus large, un plastron concave, une carapace plus bombée et une queue plus longue[3]. Le plastron des juvéniles et des femelles est plat mais celui des mâles devient concave avec l'âge[5]. La coloration du cou, du menton, et de l'intérieur des jambes est plus éclatante chez les mâles, ces dernières étant généralement jaunâtres[4].

Les nouveau-nés mesurent entre 2,8 et 3,8 cm (carapace) et leur plastron est gris-sale à brun. Leur queue est généralement de même taille que leur carapace et leur cou et leurs pattes n'ont habituellement pas de couleur vive comme les adultes[2]. De plus, leur carapace est aussi large que longue et est dépourvue de motifs pyramidaux[3].

Les tortues Terrapene carolina et Emys blandingii ont une répartition géographique qui recoupe celle de Glyptemys insculpta et sont assez similaires d'aspect. Toutefois ces deux tortues possèdent un plastron articulé qui leur permet de fermer leur carapace lorsqu'elles se cachent, ce qui n'est pas le cas de pour la Tortue des bois. Malaclemys terrapin présente également une carapace assez proche de celle de la Tortue des bois mais sa peau est grise et elle ne partage pas le même habitat, préférant les eaux saumâtres ou salées[2]. Enfin Clemmys guttata et Glyptemys muhlenbergii sont également assez similaires mais ne présentent pas les sculptures caractéristiques présentes sur la carapace de la Tortue des bois[4].

La Tortue des bois se rencontre dans une vaste zone couvrant le nord-est de l'Amérique du Nord, allant de la Nouvelle-Écosse au Minnesota d'est en ouest et au nord et jusqu'en Virginie au sud. Ceci concerne en pratique les États suivants[1] :

Environ 30 % des individus se trouvent au Canada[5]. Cette tortue forme souvent des populations d'assez petite taille et isolées les unes des autres. Dans la partie nord de sa répartition (Canada) les populations sont d'assez faible densité avec une moyenne de 0,44 individus par hectare, alors que dans le sud de sa répartition cette densité varie entre 6 et 90 individus par hectare. Les populations comprennent souvent plus de femelles que de mâles[4].

Cette espèce peut vivre près de 40 ans dans la nature et approcher 60 ans en captivité.

Au printemps cette espèce est active toute la journée et parcours en général les eaux d'un ruisseau sur plusieurs centaines de mètres, la recherche de nourriture ayant plutôt lieu en début et fin de journée[4]. Régulièrement elle se chauffe au soleil afin d'assurer sa thermorégulation, sa température corporelle pouvant alors monter à 37 °C.

Toutefois lors de très fortes chaleurs de l'été elle estive, en se reposant sous la végétation et autres débris dans des flaques peu profondes. Durant l'été elle va adopter un comportement principalement terrestre. La nuit sa température corporelle chute entre 15 et 20 °C et elle se repose alors généralement dans de petites criques ou à proximité, souvent près de broussailles[3].

À partir du mois de novembre Glyptemys insculpta limite son activité et entre en hibernation. Elle passe ainsi l'hiver au fond d'une petite rivière, seule ou en grands groupes, en s'enterrant dans la boue. Elle se déplace alors très rarement et est vulnérable aux inondations qui peuvent la surprendre.

Elle sort d'hibernation à partir du mois de mars ou avril, les mâles étant en général plus actifs en cette période que les femelles[4].

Les mâles sont agressifs, et il existe une hiérarchie, les plus gros et âgés étant les dominants. Les mâles dominés fuient en général, ou sont sujets à des coups tels des morsures, bousculades… Un mâle dominant peut même tenter d'empêcher un mâle plus « faible » de se reproduire, ce qui a donc un impact direct sur la capacité de reproduction. Cela dit bien que la taille soit généralement liée, c'est surtout l'agressivité qui détermine le vainqueur. Ces combats augmentent durant l'automne ainsi qu'au printemps, avec les accouplements[4].

Cette tortue peut se déplacer relativement rapidement (pour une tortue) avec une vitesse moyenne supérieure à 0,32 k/h, et sur de longues distances. Des études ont par ailleurs montré qu'elle possède un bon sens de l'orientation, équivalent à celui des rats, et elles sont capables de retrouver leur lieu de vie même après avoir été déplacées de 2,4 km[4].

Cette tortue est omnivore et consomme des plantes et animaux capturés à la fois sur terre et dans l'eau. Elle se nourrit de coléoptères, de mille-pattes, de limaces, ainsi que de certains champignons tels Amanita muscaria et Leccinum arcolatum, mais aussi de mousses, herbes et également parfois de charognes. Elle trouve sa nourriture en général dans la vase, les buissons et algues[4].

Cette espèce de tortue est ovipare[6]. Elle atteint sa maturité tardivement, entre 14 et 18 ans, et a une fécondité faible, mais les adultes ont un taux élevé de survie − ce qui n'est pas le cas des nouveau-nés et des jeunes[7].

Les mâles, bien qu'agressifs entre eux, ne sont pas territoriaux. La reproduction a lieu principalement au printemps et également en automne, mais peut se produire durant toute la période d'activité, parfois jusqu'en décembre[4]. Les mâles initient généralement une « danse » de séduction, en général au bord d'une rivière. Ils poussent les femelles de façon insistante, pouvant conduire à la fuite de la femelle, que le mâle va alors poursuivre. La cour se poursuit avec des mouvements d'approche et de recul, en étendant la tête, puis des balancements de tête latéraux[2]. Ces parades nuptiales peuvent durer plusieurs heures. Pour l'accouplement le mâle mord la femelle au cou afin de la chevaucher, durant 20 à 30 minutes, et ceci a généralement lieu dans l'eau à faible profondeur même si des accouplements sur la terre ferme peuvent se produire. Une femelle peut être fertilisée par de 1 à 8 mâles durant la saison, et elle peut avoir des petits issus de plusieurs mâles[4]

La ponte liée aux accouplements du printemps a lieu de mai à juillet. Les œufs sont déposés dans un sol meuble, à l'abri des inondations et bien exposé au soleil. La femelle peut parfois parcourir 250 m pour trouver un site adéquat, lequel est souvent partagé par plusieurs femelles. Avant la ponte elle peut préparer plusieurs faux nids. Elle creuse ensuite un trou de petite taille − de 5 à 10 cm de profondeur − et y dépose de 3 à 20 œufs, en moyenne 7[2], puis les recouvre.

Les œufs, ovoïdes et blancs, mesurent en moyenne 3,7 × 2,36 cm pour un poids de 12,7 g. Les œufs éclosent entre août et octobre, et font environ 3,65 cm de long[4].

Les petits grandissent vite et mesurent déjà 11,5 cm après 5 ans, et atteignent leur taille adulte (de 16,5 à 17 cm, selon le sexe) vers 16 ans.

Des cas d'hybridations entre cette espèce et Emydoidea blandingii[8] ainsi que Clemmys marmorata[9] sont rapportés.

Cette espèce a été décrite en premier par le naturaliste américain John Eatton Le Conte sous le nom de Testudo insculpta en 1830. Bien qu'ensuite placée dans le genre Clemmys est maintenant classée dans le genre Glyptemys car cette tortue et l'autre membre de ce genre, Glyptemys muhlenbergii, partagent des marqueurs génétiques spécifiques et différents du seul membre actuel du genre Clemmys, Clemmys guttata[4].

Même si aucune sous-espèce n'est reconnue il existe des différences morphologiques selon les zones où on rencontre cette tortue. Les individus vivant à l'ouest de sa répartition présentent des couleurs plus pâles au niveau des pattes et du cou que celles vivant à l'est de cette répartition. Par ailleurs les populations du sud ont une diversité génétique plus faible que les autres[4].

Par le passé la population de cette tortue s'est déplacée vers le sud à cause de l'extension des glaciers durant les épisodes glaciaires, et des vestiges de populations datant du Rancholabréen ont été trouvés jusqu'en Géorgie et au Tennessee, bien plus au sud que leur répartition actuelle. Lors du recul des glaces Glyptemys insculpta est remontée au nord jusqu'à sa répartition actuelle[4].

De nombreux animaux sont des prédateurs de la Tortue des bois, ou en tout cas constituent une menace pour elle. C'est le cas des tortues Chelydra, des porcs-épics, des ratons laveurs, des loutres, des renards et des chats, ces espèces pouvant détruire les œufs avant éclosion et s'attaquer aux jeunes. Certains animaux comme les corbeaux ou le coyote ciblent spécifiquement les nids et peuvent détruire l'intégralité d'une ponte. Cette tortue souffre également d'infestations de sangsues.

On note que les populations du nord ont tendance à avoir plus de cicatrices d'attaques que celles du sud[4].

Malgré une distribution assez étendue le nombre de Tortues des bois diminue. Ceci est en grande partie lié à l'activité humaine qui détruit son habitat, et s'y ajoutent les destructions involontaires liées au trafic routier et aux prélèvements. Les femelles, en recherche de sites de ponte, sont les principales victimes des écrasements par des véhicules. Une solution pourrait venir de la création de tunnels sous les routes pour permettre à cette espèce de se déplacer sans risque[3].

L'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN) classe d'ailleurs cette espèce comme « En danger » (EN) sur sa liste rouge[10] et la Convention sur le commerce international des espèces de faune et de flore sauvages menacées d'extinction (CITES) la place en annexe II pour la réglementation du commerce international[11].

Glyptemys insculpta

Glyptemys insculpta, la Tortue des bois, est une espèce de tortue de la famille des Emydidae, endémique de l'Amérique du Nord. Sa carapace peut atteindre de 14 à 20 cm de long et présente des motifs pyramidaux en relief sur le dessus. Son allure générale est assez semblable à celle de sa cousine la Tortue de Muhlenberg (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) − seule autre membre du genre Glyptemys − ainsi qu'aux proches Clemmys guttata et Emys blandingii.

Cette tortue se rencontre dans une vaste zone couvrant le nord-est de l'Amérique du Nord, allant de la Nouvelle-Écosse au Minnesota d'est en ouest et jusqu'en Virginie au sud. Par le passé sa répartition était beaucoup plus décalée vers le sud à cause des glaciations recouvrant le nord du continent, et des squelettes ont été retrouvés jusqu'en Géorgie. Ce reptile passe la plupart de son temps dans ou près de rivières larges et peu profondes, préférant les eaux claires et les fonds de sable. Il se rencontre également dans les forêts et prairies mais rarement loin d'une eau courante. C'est un animal diurne peu ou pas territorial qui hiberne l'hiver et estive durant les périodes les plus chaudes de l'été.