General Ecology

provided by EOL authors

Two different biologies are found among the conopids. Most conopids are endoparasites of social Hymenoptera, bees and wasps. Stylogastrine conopids are endoparasites of orthopteroids, specifically of cockroaches and crickets (Smith & Cunningham-van Somersen, 1985; Woodley & Judd, 1998). Most conopid flies are found at flowers, where mating takes place and, in many cases, females find suitable hosts in which to lay their eggs. Females attack their hosts by dorsally inserting their eggs into the abdomen. The larvae develop first by feeding on haemolymph and in their last instar attack the tissue of the thorax, weakening and then killing the host. Pupation takes place in the abdomen. Most conopids are not host specific and will strike a variety of aculeate hymenopterans (Smith, 1966). With the exception of Stylogaster, where more than one egg is laid per host, only one adult is known to emerge (Smith, 1969a; Schmid-Hempel & Schmid-Hempel, 1989). Host records are summarized by Meijere (1912), Freeman (1966), and Smith (1966). Stylogastrine conopids are mainly found in association with army ants, where they are concentrated at the front of the swarm and up to two meters in advance of the swarm (Rettenmeyer, 1961). They have not been recorded at flowers. Females seek out and dive at their hosts disturbed by the ants, using their impact to secure recurrently barbed eggs in the host cuticle (Kotrba, 1997). The larvae develop in the host the same way as other conopids. Not all stylogastrine conopids are associated with army ants as they occur in areas where there are none, so much remains to be learned about their behavior. Also, because of the chaos associated with army ant swarms, accidents do happen and other non-orthopteroid species appear to be attacked, such as tachinids, other Stylogaster, and the ants themselves. No successful rearing, however, has been noted from these other victims, but see Stuckenberg (1963) and Smith (1969b, 1979) for circumstantial evidence of parasitization of Diptera. While many conopid flies are found at flowers, thus contributing to the economy as pollinators, they are also parasites of bees. Hence, their overall importance is perhaps balanced. They have been noted as an important pest of honey bees (VanDuzee, 1934; Severin, 1937; Jamieson, 1941; Smith, 1966; Zimina, 1973; Huttinger, 1974; Mei, 1999), so in some commercial situations they are harmful. Stylogastrine conopids, which seem not to be pollinators and are only endoparasites of wild orthopteroid species, are of little economic interest to humans. Much needs to be discovered about conopid biology. Rearing conopids is an effective way to generate specimens for taxonomy and adds much needed biological information. Parasitized hosts can be easily obtained as the conopid larva always weakens its host before it completes its own development. Parasitized bees may be found at the entrance to their hives or nest or may remain in the field overnight. These parasitized host bees may be simply collected and kept, and with a little luck adult conopids will emerge. In addition to rearing, a variety of collecting methods are useful for capturing adult conopids. Malaise traps are the best type of trap to use, while hand collecting at flowers, on hilltops (Mei et al., 2009), at army ant swarms (Stylogaster only), and by sweeping are also effective. Accounts of the immature stages of conopids are widely scattered in the literature, but Ferrar (1987) gives a summary and Woodley & Judd (1998) provide additional information on Stylogaster).

Evolution

provided by EOL authors

Conopids are placed in Schizophora (Cyclorrhapha), but their exact relationships and monophyly have not been fully resolved. Hennig (1966) has reviewed the relationships among the included clades, with Camras (1994) providing further details. The stylogastrines differ from other conopids in biology and have a number of distinct characters that have led some (Rohdendorf, 1964; Smith & Cunningham-van Someren, 1985) to recognize them as a separate family. In the past most authors placed conopids next to Syrphidae, but the close resemblances are merely due to primitive similarities (symplesiomorphy). Presence of a fully developed ptilinum indicates that conopids clearly belong to Schizophora. Some authors have, however, continued to consider conopids as the sister to all other schizophorans in the group Archischiza (Chvála, 1988; Colless & McAlpine 1991). Hennig (1958) and others rejected the group because once again it is based on primitive characters and the sister-group, Muscaria, remains undefined. Most current authors view the conopids to be most closely related to the picture-winged flies (Tephritoidea) (Griffiths, 1972; McAlpine, 1989; Korneyev, 2000). Nearly 800 extant species of Conopidae have been described. They are grouped into 4 extant subfamilies (Conopinae, Dalmanniinae, Myopinae, Stylogastrinae), plus the fossil subfamily Palaeomyopinae, 8 tribes, and 47 genera. All subfamilies, 5 tribes, 14 genera and 212 species are found south of the United States. A catalog to the Neotropical species was provided by Papavero (1971), but it is now obsolete. A new conspectus is provided by us (Thompson, Skevington & Camras, 2009). Stuke & Skevington (2007) have provided the first part of a review of the Costa Rican fauna.

Diagnostic Description

provided by EOL authors

Small to large (body length 2.5-30 mm) flies. Relatively bare and elongate, usually tomentose and colored black and yellow, reddish brown or blackish, often with striking resemblance to their common hosts, wasps and bees. Head large, broader than thorax, with bare eyes, dichoptic in both sexes; proboscis usually long and slender, frequently two or more times longer than head, singly or doubly geniculate; palpus single segmented or absent. Antenna usually long, with pedicel generally longer than scape, flagellum with short, thick apical stylus (Conopinae) or dorsal arista. Ocelli usually absent in Conopinae, present in other subfamilies. Thorax subquadrate, relatively bare, though postpronotal, notopleural, supra-alar, postalar and scutellar bristles often present. Wing frequently dark along costal margin or maculate or unmarked; veins Sc, R1 and R2+3 closely aligned to costa, cell r4+5 closed or nearly closed, spurious vein usually present, cell bm much shorter than cell br, discal cell (dm) elongate, cell cup normally elongate, always closed and petiolate. Legs moderately long and usually nearly bare, although sometimes spinose; tarsi with two distinct pulvilli. Abdomen cylindrical or constricted at base. Males usually with shorter abdomen with six unmodified segments, except for Dalmanniinae, which have five; 7th and 8th segments of males modified into double cushion-shaped process beneath 5th and 6th segments. Male genitalia (excluding Stylogaster) symmetrical, simple, most complicated in Zodion. Female with seven visible abdominal segments, 8th appearing to form tip of abdomen; 5th prominently produced ventrally in form of theca in myopines, except in Myopa where this may be replaced by tuft of hairs or bristles; 7th and 8th segments prolonged and lined with palpate pads to form clasping organ, theca and these modifications absent in Dalmanniinae and Stylogastrinae; ovipositor developed in Stylogastrinae and Dalmanniinae. Sclerotized spermathecae present, 2 in Conopinae and Myopinae, 1 in Dalmanniinae and Stylogastrinae. Conopid flies are easily recognized among higher flies by a combination of characters: ptilinal suture present, lack of distinct bristles (except Stylogaster), cell r4+5 frequently petiolate; cell cup usually large (small in Stylogaster), often with short spurious vein between radial and medial fields, antenna and proboscis elongate, usually greatly so. The only group that conopids may be confused with are syrphids, but the well-developed ptilinal suture will separate these two families. Many conopids and syrphids are sorted as hymenopterans, but obviously differ in the number of wings and other characters.

Conopidae

provided by wikipedia EN

The Conopidae, usually known as the thick-headed flies, are a family of flies within the Brachycera suborder of Diptera, and the sole member of the superfamily Conopoidea. Flies of the family Conopidae are distributed worldwide in all the biogeographic realms except for the poles and many of the Pacific islands. About 800 species in 47 genera are described worldwide, about 70 of which are found in North America. The majority of conopids are black and yellow, or black and white, and often strikingly resemble wasps, bees, or flies of the family Syrphidae, themselves notable bee mimics. A conopid is most frequently found at flowers, feeding on nectar with its proboscis, which is often long.

Description

For terms see Morphology of Diptera.

Rather thinly pilose or nearly bare, elongate or stout flies of small to large size (3–20 mm, usually 5–15 mm). They are often lustrous with a black and yellow colour pattern or with reddish brown markings. The head is broad and the frons is broad in both sexes. Ocelli may be present or absent (Conopinae). Ocellar bristles are small or absent. Interfrontal bristles and vibrissae are absent. The antennae have three segments, the third bearing a dorsal bare arista or terminal style. Above the antennae is an inflatable ptilinum. The oral opening is large and the proboscis is long and slender and often geniculate. The base of the abdomen is often constricted and the genitalia of both sexes are conspicuous. In the females the genitalia are often large or greatly elongated. The wing is usually clear, in some cases with dark markings often along the costa. The costa is continuous and the subcostal vein is complete. The anal cell is closed and the first basal cell is always very long, the second moderately long. The apical cell is closed or much narrowed. Tibiae are with (Myopinae) or without dorsal preapical bristle.

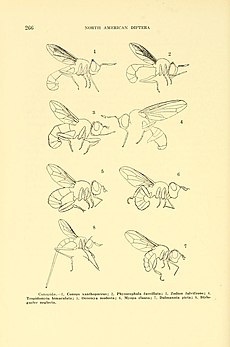

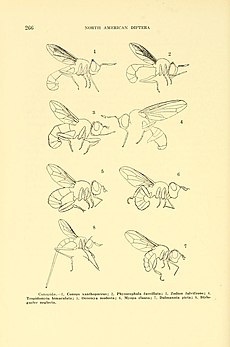

Sample genera: Conops, Dalmannia, Physocephala, Stylogaster, Myopa, and Physoconops.

Biology

The larvae of all conopids are internal parasites, most of aculeate (stinging) Hymenoptera. Adult females aggressively intercept their hosts in flight to deposit eggs. Accordingly, in the species Bombus terrestris, it has been shown that vulnerable foraging bees are likely the most susceptible to parasitism by conopids.[1] The female's abdomen is modified to form what amounts to a "can opener" to pry open the segments of the host's abdomen as the egg is inserted. The subfamily Stylogastrinae, including the genus Stylogaster, is somewhat different, in that the egg itself is shaped somewhat like a harpoon, with a rigid barbed tip, and the egg is forcibly jabbed into the host. Some species of Stylogaster are obligate associates of army ants, using the ants' raiding columns to flush out their prey. Certain members of the genus Physocephala have minor economic importance as parasites of honey bees. Some members of this genus, such as Physocephala tibialis have been shown to induce certain bumblebees to bury themselves before they die, allowing the adult fly to emerge from their hosts underground.[2][3] More research is needed to determine the life histories of most conopids.

Species lists

Identification

-

Krober. 1925. Conopidae.In: Lindner, E. (Ed.). Die Fliegen der Paläarktischen Region, 4, 4: 1-41

Keys to Palaearctic species but now needs revision (in German).

-

Séguy, E. (1934) Diptères: Brachycères. II. Muscidae acalypterae, Scatophagidae. Paris: Éditions Faune de France 28. virtuelle numérique

- Zirnjna. L.V. Family Conopidae in Bei-Bienko, G. Ya, 1988 Keys to the insects of the European Part of the USSR Volume 5 (Diptera) Part 2 English edition. Keys to Palaearctic species but now needs revision.

References

-

^ Konig, C. and P. Schmid-Hempel (1995). "Foraging and immunocompetence in workers of the bumblebee, Bombus terrestris L.". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 260: 225–227. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0084.

-

^ Malfi, Rosemary L.; Davis, Staige E.; Roulston, T'ai H. (2014-06-01). "Parasitoid fly induces manipulative grave-digging behaviour differentially across its bumblebee hosts". Animal Behaviour. 92: 213–220. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.04.005. ISSN 0003-3472.

-

^ Yong, Ed (20 May 2014). "Parasite Forces Host To Dig Its Own Grave". National Geographic. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Conopidae: Brief Summary

provided by wikipedia EN

Physocephala tibialis

Physocephala tibialis male

Thecophora

Thecophora The Conopidae, usually known as the thick-headed flies, are a family of flies within the Brachycera suborder of Diptera, and the sole member of the superfamily Conopoidea. Flies of the family Conopidae are distributed worldwide in all the biogeographic realms except for the poles and many of the Pacific islands. About 800 species in 47 genera are described worldwide, about 70 of which are found in North America. The majority of conopids are black and yellow, or black and white, and often strikingly resemble wasps, bees, or flies of the family Syrphidae, themselves notable bee mimics. A conopid is most frequently found at flowers, feeding on nectar with its proboscis, which is often long.

Conopidae morphology

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Physocephala tibialis male

Physocephala tibialis male  Thecophora

Thecophora  Conopidae morphology

Conopidae morphology