en

names in breadcrumbs

Los lepidosaurios (Lepidosauria, gr. "llagartos con escames") son un superorde de reptiles diápsidos con escames inxeríes. Inclúin a los tuátaras, llagartos, culiebres y anfisbenios. Los lepidosaurios son los reptiles actuales con mayor ésitu evolutivu.

Los lepidosaurios son consideraos usualmente como un superorde de la subclas Diapsida y tien los siguientes órdenes:

Reptilia

Lepidosauria

Los lepidosaurios (Lepidosauria, gr. "llagartos con escames") son un superorde de reptiles diápsidos con escames inxeríes. Inclúin a los tuátaras, llagartos, culiebres y anfisbenios. Los lepidosaurios son los reptiles actuales con mayor ésitu evolutivu.

Los lepidosaurios son consideraos usualmente como un superorde de la subclas Diapsida y tien los siguientes órdenes:

Squamata (llagartos, culiebres y anfisbénidos) Sphenodontia (tuatara de Nueva Zelanda)Die Überordnung der Schuppenechsen (Lepidosauria) gehört zu den Reptilien. Sie umfasst lediglich zwei Untertaxa, die Schuppenkriechtiere (Squamata) mit über 9900 Arten[1] und die Sphenodontia mit nur einer rezenten Art. Gemeinsam mit einer Reihe fossiler Tiergruppen, vor allem den als Sauropterygia bezeichneten Meeresreptilien, werden sie zu den Lepidosauromorpha zusammengefasst.

Die Schuppenechsen gehören zu den Reptilien mit diapsidem Schädel. Gegenüber anderen rezenten Reptiliengruppen wie den Schildkröten und den Krokodilen zeichnen sie sich durch viele nur ihnen gemeine Merkmale aus (Apomorphien). Hierzu gehört vor allem die querstehende Kloake, durch deren Entwicklung wahrscheinlich der im Grundmuster der Amniota vorhandene unpaare Penis der Männchen verlorenging. Des Weiteren haben die Schuppenechsen eine an der Spitze geteilte Zunge und weisen eine Reduktion des Proatlas und des Xiphisternums auf. Ein weiteres wesentliches Merkmal ist die regelmäßige Häutung des gesamten Integumentes. Insgesamt werden 48 Merkmale angegeben, die dieses Taxon als monophyletisch bestätigen.

Die Überordnung der Schuppenechsen (Lepidosauria) gehört zu den Reptilien. Sie umfasst lediglich zwei Untertaxa, die Schuppenkriechtiere (Squamata) mit über 9900 Arten und die Sphenodontia mit nur einer rezenten Art. Gemeinsam mit einer Reihe fossiler Tiergruppen, vor allem den als Sauropterygia bezeichneten Meeresreptilien, werden sie zu den Lepidosauromorpha zusammengefasst.

Tizermemmuyin timeskebrin (isem usnan: Lepidosauria) d afelafesna yeṭṭafaren astirf n temzekrin, Llan-t snat n tfesniwin deg tzermemmuyin timeskebrin

Лепидозаврлар (лат. Lepidosauria) — сойлоктордун бир классчасы.

लेपिडोसोरिया (Lepidosauria) सरीसृप (reptiles) के उन सदस्यों को कहते हैं जिनके शल्क एक-के-ऊपर-एक अतिछादी होते हैं, यानि एक शल्क का कुछ अंश दूसरे शल्क के ऊपर पड़ता है।[1]

लेपिडोसोरिया (Lepidosauria) सरीसृप (reptiles) के उन सदस्यों को कहते हैं जिनके शल्क एक-के-ऊपर-एक अतिछादी होते हैं, यानि एक शल्क का कुछ अंश दूसरे शल्क के ऊपर पड़ता है।

The Lepidosauria (/ˌlɛpɪdoʊˈsɔːriə/, from Greek meaning scaled lizards) is a subclass or superorder of reptiles, containing the orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. Squamata includes snakes, lizards, and amphisbaenians.[2] Squamata contains over 9,000 species, making it by far the most species-rich and diverse order of reptiles in the present day.[3] Rhynchocephalia was a formerly widespread and diverse group of reptiles in the Mesozoic Era.[4] However, it is represented by only one living species: the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), a superficially lizard-like reptile native to New Zealand.[5][6]

Lepidosauria is a monophyletic group (i.e. a clade), containing all descendants of the last common ancestor of squamates and rhynchocephalians.[7] Lepidosaurs can be distinguished from other reptiles via several traits, such as large keratinous scales which may overlap one another. Purely in the context of modern taxa, Lepidosauria can be considered the sister taxon to Archosauria, which includes Aves (birds) and Crocodilia. Testudines (turtles) may be related to lepidosaurs or to archosaurs, but no consensus has been reached on this subject. Lepidosauria is encompassed by Lepidosauromorpha, a broader group defined as all reptiles (living or extinct) closer to lepidosaurs than to archosaurs.

Lizards were originally split into two clades: the Iguania and the Scleroglossa. Snakes and amphisbaenians belong within the clade Scleroglossa. Analysis of teeth has indicated that Iguania is made up of the sister taxa Chamaeleonidae and Agamidae.[9] Snakes are actually a branch within the lizard group. In fact, some lizards, such as the Varanids, are more closely related to snakes than they are to other lizards. Varanids are a diverse group of lizards living from Africa, throughout south, central, and east Asia, as well as the Indo-Pacific islands and Australia.

Snakes currently have about 3,070 extant species, which are grouped into the scolecophidians and the alethinophidians.[10] The scolecophidians comprise about 370 species and are represented by small snakes with a limited gape size.[10] The alethinophidians comprise about 2,700 species and are represented by the more common snakes.[10] As snakes evolved, their gape size increased from the narrowness of the scolecophidians, which allowed for the digestion of larger prey. There are about 600 species of venomous snakes, which all belong to Caenophidia,[10] although the majority of caenophidians are non-venomous colubrids.

While amphisbaenians are mostly limbless, three species have reduced forms of front limbs. Morphological data shows that species with front limbs form a sister group to those that are limbless. This means that the amphisbaenians’ loss of limbs occurred only once.[10]

A genetic study on the genome of the tuatara suggests a divergence rate of around 240 million years ago during the Triassic.[11]

Snakes do not have an extensive fossil record; the oldest known fossil is from between early and late Cretaceous period.[9] There were Tertiary fossil snakes that became extinct by the end of the Eocene period. The first colubrid also appeared in the Eocene period.[9] Lizards first appeared in the middle Jurassic period, and this is when the scincomorph and the anguimorph lizards were first seen. The Gekkotans first appear in the late Jurassic period and the iguanians first appear in the late Cretaceous period.[9] The lizards of the Cretaceous period represent extinct genera and species.[12] The majority of amphisbaenians first appeared during the early Cenozoic period.[10] Rhynchocephalian fossils first appear in the Middle Triassic period, between 238-240 million years ago, making them the earliest lepidosaurian fossils found to date.[1] The tuatara can now only be found on small islands off the New Zealand coast. However, fossil records show that it once lived on mainland New Zealand and Rhynchocephalia as a whole was once distributed globally.[13]

The Rhynchocephalia originated by the Middle Triassic period and were distributed worldwide.[14] Except for the single species of tuatara that now lives in New Zealand, all species became extinct in the late Cretaceous, although material is known from the Miocene of New Zealand. This extinction is associated with the introduction of mammals, such as rats. The modern tuatara's skull anatomy is significantly different from the best known Mesozoic taxa.[15] Wild populations of tuatara can be found on 32 islands; in addition to three islands in which populations have formed due to migration.[5]

Extant reptiles are in the clade Diapsida, named for a pair of temporal fenestrations on each side of the skull.[16] Until recently, Diapsida was said to be composed of Lepidosauria and their sister taxa Archosauria.[9] The subclass Lepidosauria is then split into Squamata[17] and Rhynchocephalia. More recent morphological studies[18][19] and molecular studies[20][21][22][23][24][25] also place turtles firmly within Diapsida, even though they lack temporal fenestrations.

The group Squamata[17] includes snakes, lizards, and amphisbaenians. Squamata can be characterized by the reduction or loss of limbs. Snakes, some lizards, and most amphisbaenians have evolved the complete loss of their limbs. The skin of all squamates is covered in scales. The upper jaw of Squamates is movable on the cranium, a configuration called kinesis.[13] This is made possible by a loose connection between the quadrate and its neighboring bones.[26] Without this, snakes would not be able consume prey that are much larger than themselves. However, the tuatara does not share this characteristic with the other Lepidosauria. Amphisbaenians are mostly legless like snakes, but are generally much smaller. Three species of amphisbaenians have kept reduced front limbs and these species are known for actively burrowing in the ground.[10]

Rhynchocephalia, which includes the tuatara and their extinct relatives, can presently only be found on some small islands off New Zealand. The tuatara has amphicoelous vertebrae, which means that the vertebrae are hollowed out at both ends.[13] Tuataras also have the ability to autotomize their tails. A well-developed median or pineal eye is present on the top of the head (parietal region) and an additional row of upper teeth is located on the palatine bone.[9]

The reptiles in the subclass Lepidosauria can be distinguished from other reptiles by a variety of characteristics.[27] First, the males have evolved a hemipenis instead of a single penis with erectile tissue that is found in crocodilians, birds, mammals, and turtles. The hemipenis can be found in the base of the tail. The tuatara has not fully evolved the hemipenis, but instead has shallow paired outpocketings of the posterior wall of the cloaca that have been determined to be precursors to the hemipenis.[9]

Second, most lepidosaurs have the ability to autotomize their tails. However, this trait has been lost on some recent species. In lizards, fracture planes are present within the vertebrae of the tail that allow for its removal. Some lizards have multiple fracture planes, while others just have a single fracture plane. The regrowth of the tail is not always complete and is made of a solid rod of cartilage rather than individual vertebrae.[9] In snakes, the tail separates between vertebrae and some do not experience regrowth.[9]

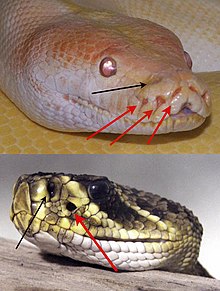

Third, the scales in lepidosaurs are horny (keratinized) structures of the epidermis, allowing them to be shed collectively, contrary to the scutes seen in other reptiles.[9] This is done in different cycles, depending on the species. However, lizards generally shed in flakes while snakes shed in one piece. Unlike scutes, lepidosaur scales will often overlap like roof tiles.

Squamates are represented by viviparous, ovoviviparous, and oviparous species. Viviparous means that the female gives birth to live young, Ovoviviparous means that the egg will develop inside the female's body and Oviparous means that the female lays eggs. A few species within Squamata have the ability to reproduce asexually.[28] The tuatara lays eggs that are usually about one inch in length and which take about 14 months to incubate.[13]

While in the egg, the Squamata embryo develops an egg tooth on the premaxillary that helps the animal emerge from the egg.[12] A reptile will increase three to twentyfold in length from hatching to adulthood.[12] There are three main life history events that lepidosaurs reach: hatching/birth, sexual maturity, and reproductive senility.[12]

Because gular pumping is so common in lepidosaus, and is also found in the tuatara, it is assumed that it is an original trait in the group.[29]

Most lepidosaurs rely on camouflage as one of their main defenses. Some species have evolved to blend in with their ecosystem, while others are able change their skin color to blend in with their current surroundings. The ability to autotomize the tail is another defense that is common among lepidosaurs. Other species, such as the Echinosauria, have evolved the defense of feigning death.[12]

Viperines can sense their prey's infrared radiation through bare nerve endings on the skin of their heads.[12] Also, viperines and some boids have thermal receptors that allow them to target their prey's heat.[12] Many snakes are able to obtain their prey through constriction. This is done by first biting the prey, then coiling their body around the prey. The snake then tightens its grip as the prey struggles, which leads to suffocation.[12] Some snakes have fangs that produce venomous bites, which allows the snake to consume unconscious, or even dead, prey. Also, some venoms include a proteolytic component that aids in digestion.[12] Chameleons grasp their prey with a projectile tongue. This is made possible by a hyoid mechanism, which is the contraction of the hyoid muscle that drives the tip of the tongue outwards.[12]

Within the subclass Lepidosauria there are herbivores, omnivores, insectivores, and carnivores. The herbivores consist of iguanines, some agamids, and some skinks.[12] Most lizard species and some snake species are insectivores. The remaining snake species, tuataras, and amphisbaenians, are carnivores. While some snake species are generalist, others eat a narrow range of prey - for example, Salvadora only eat lizards.[12] The remaining lizards are omnivores and can consume plants or insects. The broad carnivorous diet of the tuatara may be facilitated by its specialised shearing mechanism, which involves a forward movement of the lower jaw following jaw closure.[30]

While birds, including raptors, wading birds and roadrunners, and mammals are known to prey on reptiles, the major predator is other reptiles. Some reptiles eat reptile eggs, for example the diet of the Nile monitor includes crocodile eggs, and small reptiles are preyed upon by larger ones.[12]

The geographic ranges of lepidosaurs are vast and cover all but the most extreme cold parts of the globe. Amphisbaenians exist in Florida, mainland Mexico, including Baja California, the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and the Caribbean.[26] The tuatara is confined to only a few rocky islands of New Zealand, where it digs burrows to live in and preys mostly on insects.[13]

Climate change has led to the need for conservation efforts to protect the existence of the tuatara. This is because it is not possible for this species to migrate on its own to cooler areas. Conservationists are beginning to consider the possibility of translocating them to islands with cooler climates.[31] The range of the tuatara has already been minimized by the introduction of cats, rats, dogs, and mustelids to New Zealand.[32] The eradication of the mammals from the islands where the tuatara still survives has helped the species increase its population. An experiment observing the tuatara population after the removal of the Polynesian rat showed that the tuatara expressed an island-specific increase of population after the rats' removal.[33] However, it may be difficult to keep these small mammals from reinhabiting these islands.

Habitat destruction is the leading negative impact of humans on reptiles. Humans continue to develop land that is important habitat for the lepidosaurs. The clear-cutting of land has also led to habitat reduction. Some snakes and lizards migrate toward human dwellings because there is an abundance of rodent and insect prey. However, these reptiles are seen as pests and are often exterminated.[9]

Snakes are commonly feared throughout the world. Bounties were paid for dead cobras under the British Raj in India; similarly, there have been advertised rattlesnake roundups in North America. Data shows that between 1959 and 1986 an average of 5,563 rattlesnakes were killed per year in Sweetwater, Texas, due to rattlesnake roundups, and these roundups have led to documented declines and local extirpations of rattlesnake populations, especially Eastern Diamondbacks in Georgia.[9]

People have introduced species to the lepidosaurs' natural habitats that have increased predation on the reptiles. For example, mongooses were introduced to Jamaica from India to control the rat infestation in sugar cane fields. As a result, the mongooses fed on the lizard population of Jamaica, which has led to the elimination or decrease of many lizard species.[9] Actions can be taken by humans to help endangered reptiles. Some species are unable to be bred in captivity, but others have thrived. There is also the option of animal refuges. This concept is helpful to contain the reptiles and keep them from human dwellings. However, environmental fluctuations and predatorial attacks still occur in refuges.[12]

Reptile skins are still being sold. Accessories, such as shoes, boots, purses, belts, buttons, wallets, and lamp shades, are all made out of reptile skin.[9] In 1986, the World Resource Institute estimated that 10.5 million reptile skins were traded legally. This total does not include the illegal trades of that year.[9] Horned lizards are popularly harvested and stuffed.[9] Some humans are making a conscious effort to preserve the remaining species of reptiles, however.

The Lepidosauria (/ˌlɛpɪdoʊˈsɔːriə/, from Greek meaning scaled lizards) is a subclass or superorder of reptiles, containing the orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. Squamata includes snakes, lizards, and amphisbaenians. Squamata contains over 9,000 species, making it by far the most species-rich and diverse order of reptiles in the present day. Rhynchocephalia was a formerly widespread and diverse group of reptiles in the Mesozoic Era. However, it is represented by only one living species: the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), a superficially lizard-like reptile native to New Zealand.

Lepidosauria is a monophyletic group (i.e. a clade), containing all descendants of the last common ancestor of squamates and rhynchocephalians. Lepidosaurs can be distinguished from other reptiles via several traits, such as large keratinous scales which may overlap one another. Purely in the context of modern taxa, Lepidosauria can be considered the sister taxon to Archosauria, which includes Aves (birds) and Crocodilia. Testudines (turtles) may be related to lepidosaurs or to archosaurs, but no consensus has been reached on this subject. Lepidosauria is encompassed by Lepidosauromorpha, a broader group defined as all reptiles (living or extinct) closer to lepidosaurs than to archosaurs.

Los lepidosaurios (Lepidosauria, griego. "lagartos con escamas") son un superorden de saurópsidos diápsidos con escamas imbricadas. Incluyen a los tuátaras, lagartos, serpientes y anfisbenios. Los lepidosaurios son los reptiles actuales con mayor éxito evolutivo.

Los lepidosaurios son considerados usualmente como un superorden de la subclase Diapsida y abarca los siguientes órdenes:

Soomussisalikud (Lepidosauria) on roomajate klassi kuuluv ülemselts, vahel ka alamklass.

Ülemseltsi kuuluvad järgmised seltsid:

Lepidosauria azpiordenako narrasti bat da, gaur egun ordezkari bakarra duena.

Lepidosauria azpiordenako narrasti bat da, gaur egun ordezkari bakarra duena.

(RLQ=window.RLQ||[]).push(function(){mw.log.warn("Gadget "ErrefAurrebista" was not loaded. Please migrate it to use ResourceLoader. See u003Chttps://eu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berezi:Gadgetaku003E.");});Les Lépidosauriens, ou Lepidosauria, sont un super-ordre de reptiles de la sous-classe des diapsides. Il comprend d'une part les rhynchocéphales (les sphénodontiens) et d'autre part, les squamates (lézards, serpents, iguanes) actuels ou éteints.

Selon BioLib (8 avril 2021)[1] :

Les Lépidosauriens, ou Lepidosauria, sont un super-ordre de reptiles de la sous-classe des diapsides. Il comprend d'une part les rhynchocéphales (les sphénodontiens) et d'autre part, les squamates (lézards, serpents, iguanes) actuels ou éteints.

Selon BioLib (8 avril 2021) :

ordre Rhynchocephalia Williston, 1925 -- Sphénodons ordre Squamata Oppel, 1811 -- Tous les autres « reptiles » contemporains à l'exclusion des tortues et crocodiles (et oiseaux)

Uma inornata

Clasificación científica Reino: Animalia Filo: Chordata Clase: Reptilia Sublase: Sauropsida Infraclase: Lepidosauromorpha Superorde: Lepidosauria OrdesOs lepidosauros ou lepidosauria forman o maior grupo dos réptiles (excepto o das aves), contendo máis de 4.000 especies de lagartos e 2.700 especies de serpes, ademais das dúas especies de tuátara. Son tetrápodos maiormente terrestres, con algunhas especies secundariamente acuáticas, especialmente entre as serpentes. O tegumento dos lepidosauria estaba cubertos por escamas e eran relativamente impermeables á auga.

Os lepidosauros son considerados usualmente como un superorde da subclase Sauropsida e abrangue os seguintes ordes:

Os lepidosauros ou lepidosauria forman o maior grupo dos réptiles (excepto o das aves), contendo máis de 4.000 especies de lagartos e 2.700 especies de serpes, ademais das dúas especies de tuátara. Son tetrápodos maiormente terrestres, con algunhas especies secundariamente acuáticas, especialmente entre as serpentes. O tegumento dos lepidosauria estaba cubertos por escamas e eran relativamente impermeables á auga.

Lepidosauria (dari bahasa Yunani yang berarti kadal bersisik) adalah reptil dengan sisik tumpang tindih. Subkelas ini meliputi Squamata dan Rhynchocephalia. Ini adalah kelompok monofiletik dan karena itu berisi semua keturunan dari nenek moyang yang sama.[1] Squamata termasuk ular, kadal, dan amphisbaenia.[2] Rhynchocephalia adalah kelompok luas dan beragam 220-100 juta tahun yang lalu;[3] namun, hal itu sekarang diwakili hanya oleh genus Sphenodon, yang berisi dua spesies tuatara, asli Selandia Baru.[4][5] Lepidosauria adalah takson saudari dari Archosauria, yang meliputi Aves dan Crocodilia. Kadal dan ular adalah kelompok yang paling banyak spesiesnya dari Lepidosauria dan, dikombinasikan, mengandung lebih dari 9.000 spesies.[6] Ada banyak perbedaan morfologi yang membedakan kadal, tuatara, dan ular.

Lepidosauria (dari bahasa Yunani yang berarti kadal bersisik) adalah reptil dengan sisik tumpang tindih. Subkelas ini meliputi Squamata dan Rhynchocephalia. Ini adalah kelompok monofiletik dan karena itu berisi semua keturunan dari nenek moyang yang sama. Squamata termasuk ular, kadal, dan amphisbaenia. Rhynchocephalia adalah kelompok luas dan beragam 220-100 juta tahun yang lalu; namun, hal itu sekarang diwakili hanya oleh genus Sphenodon, yang berisi dua spesies tuatara, asli Selandia Baru. Lepidosauria adalah takson saudari dari Archosauria, yang meliputi Aves dan Crocodilia. Kadal dan ular adalah kelompok yang paling banyak spesiesnya dari Lepidosauria dan, dikombinasikan, mengandung lebih dari 9.000 spesies. Ada banyak perbedaan morfologi yang membedakan kadal, tuatara, dan ular.

I lepidosauri (Lepidosauria - dal greco λεπισ, lepis - "squama", e σαύρος, sauros - "lucertola") sono un gruppo di rettili, caratterizzati da un corpo ricoperto da squame sovrapposte. Il gruppo include i tuatara, le lucertole, i serpenti e gli anfisbeni. I lepidosauri sono i rettili attuali di maggior successo.

In tassonomia, i lepidosauri ("rettili con le scaglie") sono un superordine di rettili che comprende due ordini attuali:

A questi si aggiunge un altro ordine conosciuto solo allo stato fossile, spesso inserito in un gruppo a sé stante:

Lepidosauria (-orum, n.pl. e Graeco λεπισ = lepis, et σαύρος = lacerta) sunt Reptilia Diapsida una fenestra temporali nec fenestra antorbitali in cranio. ordines duo tantum agnoscuntur: Sphenodontia (Sphenodon propinquaque exstincta) et Squamata (lacertilia, Amphisbaenia, Serpentes et similia).

─o Lepidosauromorpha ├── Acerosodontosaurus † ├?─ Sauropterygia † └─o Lepidosauriformes ├── Eolacertilia *? † └─o Lepidosauria ├── Sphenodontia ─> Sphenodon └─o Squamata Oppel, 1811 ├── Dibamidae └─o Bifurcata ├── Gekkota └─o Unidentata ├── Scinciformata └─o Episquamata ├── Laterata ─> Amphisbaenia └─o Toxicofera ├── Pythonomorpha ─> Serpentes └─┬── Iguania └── Anguimorpha

Lepidosauria (-orum, n.pl. e Graeco λεπισ = lepis, et σαύρος = lacerta) sunt Reptilia Diapsida una fenestra temporali nec fenestra antorbitali in cranio. ordines duo tantum agnoscuntur: Sphenodontia (Sphenodon propinquaque exstincta) et Squamata (lacertilia, Amphisbaenia, Serpentes et similia).

Os Lepidosauria (do grego lepidos, escama + sauros, lagarto) formam um dos maiores grupos da Reptilia, contendo mais de 4.000 espécies de lagartos e 2.700 espécies de serpentes, além das duas espécies de tuataras. São tetrápodes predominantemente terrestres, com algumas espécies secundariamente aquáticas, principalmente entre as serpentes. O tegumento dos Lepidosauria é coberto por escamas e é relativamente impermeável à água. Os tuataras e a maioria dos lagartos possuem quatro membros, mas a redução ou perda completa dos membros é comum entre lagartos e todas as serpentes são ápodas. Apresentam fenda cloacal transversal, ao invés da fenda longitudinal que caracteriza os outros tetrápodes.

Dentro dos Lepidosauria, os Sphenodontidae (tuataras) formam o grupo irmão dos Squamata (lagartos e serpentes). Dentro dos Squamata, os lagartos podem ser distinguidos das serpentes em termos coloquiais, mas não filogeneticamente, porque as serpentes são derivadas dos lagartos. Assim sendo, os "lagartos" formam um grupo parafilético. No entanto, lagartos e serpentes são distintos em muitos aspectos da sua ecologia e comportamento e uma separação coloquial torna-se útil em seu estudo.

Segue Benton (2004):

Os Lepidosauria (do grego lepidos, escama + sauros, lagarto) formam um dos maiores grupos da Reptilia, contendo mais de 4.000 espécies de lagartos e 2.700 espécies de serpentes, além das duas espécies de tuataras. São tetrápodes predominantemente terrestres, com algumas espécies secundariamente aquáticas, principalmente entre as serpentes. O tegumento dos Lepidosauria é coberto por escamas e é relativamente impermeável à água. Os tuataras e a maioria dos lagartos possuem quatro membros, mas a redução ou perda completa dos membros é comum entre lagartos e todas as serpentes são ápodas. Apresentam fenda cloacal transversal, ao invés da fenda longitudinal que caracteriza os outros tetrápodes.

Dentro dos Lepidosauria, os Sphenodontidae (tuataras) formam o grupo irmão dos Squamata (lagartos e serpentes). Dentro dos Squamata, os lagartos podem ser distinguidos das serpentes em termos coloquiais, mas não filogeneticamente, porque as serpentes são derivadas dos lagartos. Assim sendo, os "lagartos" formam um grupo parafilético. No entanto, lagartos e serpentes são distintos em muitos aspectos da sua ecologia e comportamento e uma separação coloquial torna-se útil em seu estudo.

인룡(鱗龍; Lepidosaurs, →비늘이 있는 도마뱀)은 인룡상목(鱗龍上目; Lepidosauria)에 속한 파충류들로, 겹치는 비늘을 갖고 있다. 여기에는 뱀목과 훼두목이 포함된다. 인룡류는 단계통군이며 공통조상의 모든 후손을 포함한다. 뱀목은 뱀, 도마뱀, 그리고 지렁이도마뱀을 포함한다. 스페노돈티드과는 2억 년 전에는 훨씬 널리 분포했고 다양했지만 지금은 뉴질랜드에 사는 투아타라 두 종만이 남아있다. 인룡류의 자매분류군은 조강과 악어를 포함하는 지배파충류이다. 현존하는 투아타라는 스페노돈티드과의 스페노돈 속에 속한다. 도마뱀과 뱀은 인룡류 중 가장 종류가 많은 그룹으로 합쳐서 7970 종에 달한다.[1] 뉴질랜드에 서식하는 투아타라는 두 종만이 남아 있다. 도마뱀과 투아타라, 그리고 뱀 사이에는 뚜렷한 형태적 차이가 있다.

파충류의 하위분류인 인룡류는 다른 파충류와 몇 가지 차이점을 가진다. 먼저 수컷은 악어, 새, 포유류, 그리고 거북에게서 볼 수 있는 발기가 되는 음경이 아닌, 반음경을 가진다. 반음경은 꼬리가 시작되는 부분에서 볼 수 있다. 투아타라에서는 반음경이 완전히 진화하지 않았으나 총배설강의 뒤쪽에 한 쌍의 얕은 주머니를 가지고 있어 이것이 나중에 반음경으로 진화했다고 보고 있다.[2]

두번째로, 거의 대부분의 인룡류는 스스로 꼬리를 자를 수 있는 능력을 가지고 있다. 이 능력은 일부 최근 종에서는 없어졌다. 도마뱀은 꼬리뼈 안에 쪼개짐면이 있어서 꼬리를 떼어낼 수 있게 되어 있다. 어떤 도마뱀은 쪼개짐면이 여러 개 있기도 하고 어떤 도마뱀은 하나만 가지고 있다. 꼬리 재생은 항상 완벽한 것은 아니며 개개의 척추가 아닌 연골로 된 막대로 구성된다.[2] 뱀에서는 꼬리가 척추뼈 사이에서 분리되며 다시 자라나지 않는다.[2]

세번째로 인룡류의 비늘은 케라틴으로 된 상피 조직으로, 허물을 벗을 수 있게 되어 있다. 다른 파충류에서 볼 수 있는 인갑(scute)과는 다르다.[2] 탈피는 종에 따라 다른 주기로 이루어진다. 도마뱀은 대개 조각조각 허물을 벗지만 뱀은 통째로 벗는다. 인갑과 달리 인룡류의 비늘은 기와처럼 겹쳐있는 구조를 하고 있다.

현생 파충류는 무궁류와 이궁류, 두 계통군으로 나뉜다. 각 계통군의 이름은 머리뼈에 있는 측두창의 개수에 따라 지어졌다. 무궁류는 측두창이 없고 이궁류는 머리뼈의 양쪽에 각각 두 개 씩 측두창을 가지고 있다.[3] 무궁류에는 거북과 멸종한 근연종들만이 속한다. 이궁류는 인룡류와 자매 분류군인 지배파충류로 구성된다.[2] 인룡류는 뱀목과 스페노돈티드과로 나뉜다.

뱀목은 뱀, 도마뱀, 그리고 지렁이도마뱀을 포함한다. 뱀목은 다리가 줄어들거나 없어지는 특징이 있다. 뱀, 어떤 도마뱀, 그리고 거의 대부분의 지렁이도마뱀은 다리를 완전히 잃어버렸다. 모든 뱀목의 피부는 비늘로 덮여 있다. 뱀목의 위턱은 머리뼈와 별도로 움직일 수 있는 무정위 운동성(cranial kinesis)를 가지고 있다.[4] 방형골(quadrate)과 그 이웃한 뼈 사이가 느슨하게 연결되어 있기 때문에 이런 움직임이 가능하다.[5] 무정위 운동성이 없었다면 뱀들은 자신보다 큰 먹이를 삼킬 수 없었을 것이다. 투아타라는 다른 인룡류와 달리 이 특징을 가지고 있지 않다. 지렁이도마뱀은 뱀처럼 거의 대부분 다리가 없거나, 보통 훨씬 작다. 지렁이도마뱀 중 세 종은 앞다리를 가지고 있으며 이들은 땅을 파고 들어가 생활한다.[1]

스페노돈티드과는 투아타라와 멸종한 근연종을 포함하며 뉴질랜드 근처의 작은 섬들에서만 발견된다. 투아타라는 앞뒤가 모두 움푹 들어간 척추뼈를 가지고 있다.[4] 투아타라는 또 꼬리를 스스로 잘라내는 능력도 가지고 있다. 투아타라는 정수리의 마루뼈 부근에 잘 발달된 솔방울눈 (pineal eye)을 가지고 있고, 이빨은 상대적으로 큰 편이다.[2]

뱀은 화석 기록이 그리 많지 않은 편이지만 가장 오래된 뱀 화석은 백악기의 것이다.[2] 에오세 말기에 멸종한 3 기의 뱀 화석이 몇 종류 발견되었다. 최초의 뱀과 역시 에오세에 나타났다.[2] 도마뱀은 쥐라기에 처음 출현했고 이 때 도마뱀류(scincomorph)과 무족도마뱀류(anguimorph)가 처음 발견된다. 도마뱀붙이류(gekko)는 후기 쥐라기에 나타나고 이구아나류는 후기 백악기에 처음 나타났다. 백악기의 도마뱀들은 거의 대부분 멸종한 속 및 종들에 속한다.[6]다수의 지렁이도마뱀류는 초기 신생대에 처음 나타난다.[1] 스페노돈티드목의 화석 기록은 하부 트라이아스기 지층에서 처음 발견되는데 이것이 인룡류 최초의 화석기록이다. 투아타라는 현재 뉴질랜드에서 조금 떨어진 작은 섬들에서만 발견된다. 하지만 화석 기록에 의하면 뉴질랜드 본섬 뿐 아니라 전세계에 걸쳐 살았던 것을 알 수 있다.[4]

인룡류는 원래 이구아니아와 스클레로글로사 두 개의 계통군으로 나뉘었다. 뱀과 지렁이도마뱀은 스클레로글로사 계통군에 속한다. 이빨을 분석한 결과에 의하면 이구아니아는 카멜레오니드과와 아가미드과 두 개의 자매분류군으로 나뉜다.[2] 뱀은 인룡류 그룹 내부의 한 가지이다. 실제로 왕도마뱀류와 같은 일부 도마뱀은 다른 도마뱀들보다 뱀과 더 가까운 관계에 있다. 왕도마뱀류는 반수생이며 큰 몸집을 가진 육식성 도마뱀으로 호주에 산다.[7]

뱀은 현재 약 3070 개의 현생 종을 가지고 있으며 스콜레코피디안과 알레티노피디안으로 나뉜다.[1] 스콜레코피디안에는 370 종 정도가 속하며 입을 그리 크게 벌릴 수 없는 작은 뱀들로 대표된다.[1] 뱀은 작은 입을 가진 스콜레코피디안으로부터 입이 커지는 방향으로 진화했다. 이로 인해 큰 먹이감을 소화할 수 있게 되었다. 독사는 약 2500 종 정도가 있으며 모두 뱀상과에 속한다.[1]

지렁이도마뱀류는 거의 대부분 다리를 가지고 있지 않지만 세 종은 조그마한 앞다리를 가지고 있다. 형태학적 자료에 의하면 앞다리를 가진 종들은 다리가 없는 종류의 자매그룹이다. 이것은 지렁이도마뱀의 진화과정에서 다리를 잃어버리는 사건이 한 번만 일어났다는 것을 의미한다.[1]

투아타라는 트라이아스기에 기원하여 전세계에 분포하고 있었다. 후기 백악기에 모두 멸종하고 두 종만이 현재 뉴질랜드에 살아남아 있다. 이들의 멸종은 대형포유류의 출현과 시기를 같이 한다. 현생 투아타라의 골격 구조는 트라이아스기에 살았던 종의 구조와 거의 유사하다. 투아타라의 야생 개체군은 32 개의 섬에서 발견되며 추가로 세 개의 섬에 이주한 것이 알려져 있다.[8]

다음은 2013년 피론(Pyron, R.A.) 등의 연구에 기초한 계통 분류이다.[9]

인룡상목 뱀목인룡류에는 초식, 잡식, 충식, 그리고 육식을 하는 종류가 모두 포함되어 있다. 초식을 하는 인룡류는 이구아나류, 아가미드류, 그리고 일부 도마뱀들이다.[6] 대부분의 도마뱀과 어떤 뱀들은 곤충을 주로 먹는다. 그 외의 뱀, 투아타라, 그리고 지렁이도마뱀은 육식성이다. 어떤 뱀은 특정한 종류의 먹이만을 먹는다. 예를 들면 살바도라 속의 뱀은 도마뱀만을 먹는다.[6] 나머지 도마뱀들은 잡식성이며 식물이나 곤충을 먹을 수 있다.

독사아과(viperines)의 뱀들은 머리의 피부에 노출되어 있는 신경말단으로 먹잇감이 방출하는 적외선을 감지할 수 있다.[6] 또, 독사아과와 보아뱀과의 어떤 뱀들은 열을 감지하여 먹잇감의 위치를 찾을 수 있다.[6] 많은 뱀들이 먹이를 졸라서 죽일 수 있다. 먼저 먹잇감을 물고 자신의 몸을 그 주위로 둥글게 감는다. 몸을 세게 조이면 먹잇감은 질식하여 죽는다.[6] 어떤 뱀들은 독을 낼 수 있는 송곳니를 가지고 있다. 독니를 이용하여 뱀은 이미 죽었거나 의식을 잃은 먹이를 잠아먹는다. 또 어떤 독은 단백질분해 성분을 가지고 있어 소화를 돕기도 한다.[6] 카멜레온은 길게 발사할 수 있는 혀로 먹이를 잡는다. 독특한 혀 메카니즘을 통해서 가능한데, 혀의 근육을 수축시켜 혀의 끝부분을 바깥쪽으로 밀어내는 방식이다.[6]

파충류의 주요 포식자는 다른 파충류들이다. 큰 파충류들은 작은 파충류들을 잡아먹는다. 또 파충류의 알도 파충류가 먹는다. 게다가 새들도 파충류를 잡아먹는다. 맹금류, 섭금류, 로드러너 등이 파충류를 잡아먹는 새들이다. 포유류도 파충류를 잡아먹는 것으로 알려져 있다.[6]

뱀과 도마뱀은 분포가 매우 넓어서 극단적으로 추운 부분을 제외하면 전세계적으로 분포한다. 지렁이도마뱀은 플로리다, 멕시코 본토와 바하 캘리포니아, 지중해, 중동, 북아프리카, 사하라이남 아프리카, 남아메리카, 그리고 카리브해 지역에 산다.[5] 투아타라는 뉴질랜드의 몇몇 돌섬에만 산다. 투아타라는 땅을 파고 살며 주로 곤충을 잡아먹는다.[4]

뱀목은 태생, 난태생, 그리고 난생을 보여주는 종들을 모두 가지고 있다. 태생은 암컷이 새끼를 낳는다는 의미이고, 난태생은 알이 암컷의 몸속에서 새끼로 자란다는 의미이다. 난생인 종들은 암컷이 알을 낳는다. 뱀목의 몇몇 종들은 무성생식을 할 수 있다.[7] 투아타라는 길이 1 인치 정도의 알을 낳는다. 이 알은 14 개월 후에 부화한다.[4]

뱀목은 알 속에 있을 때 전상악골에 난치(卵齒; egg tooth)가 발달하여 부화 시에 알을 깨고 나오는 것을 돕는다.[6] 파충류는 알에서 깨어났을 때부터 성체가 될 때까지 세 배에서 스무 배까지 성장한다.[6] 인룡류의 생활사에는 크게 세 가지 중요한 사건이 있다. 부화/탄생, 성적 성숙, 그리고 생식능력의 상실이 그것이다.[6]

거의 대부분의 인룡류는 보호색을 주요 방어수단으로 사용한다. 어떤 종들은 생태계에 잘 섞여들어갈 수 있는 피부색을 진화시킨 반면 어떤 종들은 현재 환경에 맞게 피부색을 변화시키기도 한다. 꼬리를 스스로 자를 수 있는 능력은 인룡류에서 흔한 방어수단이다. 에키노사우리아 같은 종류는 죽은 척 하는 방어기작을 진화시켰다.[6]

뱀은 흔히 공포의 대상이다. 북아메리카에서는 방울뱀 라운드업이 열리곤 한다. 1959년부터 1986년 사이에 스위트워터, 텍사스에서 열리는 방울뱀 라운드업 때문에 매년 5,563 마리의 방울뱀이 죽임을 당했다는 자료가 있다. 이때문에 그 지역의 방울뱀 개체군이 쇠퇴하고 특히 조지아의 동부다이아몬드방울뱀이 부분적으로 자생지가 절멸했다고 한다.[2]

인간에 의한 서식지파괴가 파충류에게 가장 큰 부정적 영향을 끼친다. 사람들은 계속해서 인룡류의 중요한 서식지였던 땅을 개발한다. 땅을 정비하는 것 역시 서식지의 축소를 가져온다. 어떤 뱀과 도마뱀들은 설치류와 곤충이 풍부한 인간의 거주지로 이주하기도 한다. 하지만 이 파충류들은 해수로 간주되어 박멸의 대상이 된다.[2]

사람들은 인룡류의 서식지에 다른 종들을 데리고 들어오면서 파충류가 먹잇감이 되는 일이 많아졌다. 자메이카의 사탕수수밭에 창궐하는 쥐를 잡기 위해 인도에서 몽구스를 데리고 들어온 것이 대표적인 예다. 그 결과 몽구스는 자메이카의 도마뱀 개체군을 먹이로 삼았고 많은 도마뱀 종들이 절멸되거나 수가 크게 줄어들었다.[2]

적절한 행동으로 멸종위기의 파충류를 도울 수도 있다. 어떤 종은 포획된 상태에서는 번식을 하지 못하지만 다른 종류들은 잘 번식해 왔다. 동물피난처를 만드는 방법도 있다. 이 개념은 파충류를 특정 지역 안에서만 살게 해서 사람들의 거주지에 오지 못하게 만들 수 있다. 하지만 환경변화와 포식자의 공격은 피난처 안에서도 일어난다.[6]

불행히도, 파충류의 가죽은 계속해서 팔리고 있다. 신발, 부츠, 가방, 벨트, 버튼, 지갑, 그리고 전등갓 등의 악세사리를 만드는 데 파충류 가죽이 쓰인다.[2] 1986년에 세계자원기관(World Resource Institute)은 1050만 마리의 파충류 가죽이 합법적으로 거래되었다고 추산했다. 이것은 불법적인 거래는 포함하지 않은 것이다.[2] 뿔도마뱀을 잡아서 박제로 만든 것이 인기가 많다.[2] 남아 있는 파충류 종들을 보존하기 위해 사람들이 의식적인 노력을 기울여야 할 것이다.

기후변화는 투아타라를 보존하기 위한 야생동물 관리의 필요성을 높였다. 투아타라는 더 서늘한 기후로 이주하는 것이 불가능하기 때문이다. 보존론자들은 투아타라를 더 서늘한 기후에 있는 섬으로 강제이주 시키는 것의 가능성을 고려하기 시작했다.[10] 투라타라의 서식범위는 이미 고양이, 쥐, 개, 그리고 족제비과 동물들이 들어오면서 크게 줄어들었다.[11] 투아타라가 아직 살아남아 있는 섬들에서 이들 포유류를 박멸한 것이 투아타라 개체군 회복에 도움이 되었다. 폴리네시아 쥐의 제거 이후 투아타라 개체군을 관찰한 바에 따르면 쥐가 없어진 후 그 섬에서만 개체군의 크기가 증가했다고 한다.[12] 하지만 이들 소형 포유류가 섬에 다시 서식하게 되는 것을 막기는 어려울 수도 있다.