en

names in breadcrumbs

A negative effect directly on humans is not evident with S. purpuratus. It does, however, have an adverse effect in an indirect way. Purple sea urchins feed on the giant kelp, as mentioned previously. In their feeding, they can destroy entire forests of kelp. These kelp forests are commercially important for fisheries. They are even more important in that the blades of the kelp can be harvested for algin. Algin is a product that is used in the manufacturing of plastics and paints. It is also used as a thickening agent in foods such as gravy and pudding. Another use for algin is in making fibers that are instrumental in the manufacturing of fire resistant clothes. Without the kelp, algin could not be harvested. Strongylocentrotus purpuratus aides in the demise of the kelp forests that provide us with so many different products. (Readdie, 1998)

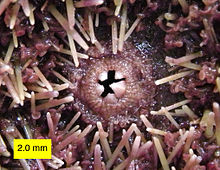

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus has a round body that consists of a radially symmetrical test, or shell, covered with large spines. The test itself ranges from 50mm in diameter to an occasional 100mm in diameter. This test is covered with spines that are generally bright purple for adults. Younger urchins have purple tinged spines that are mostly pale green in color. Also covering the test or shell, are tube feet and pedicellariae. The oral side of the urchin, on which the mouth is located, is usually the side facing the substrate (down). The aboral side of the urchin is usually the side of the urchin facing the observer (up). The body of S. purpuratus is radially semetrical. Male and female urchins are monomorphic; they are not physically distinguishable from one another. (Abbott et al., 1980; Olhausen and Russo, 1981; Ebert and Russell, 1988)

Other Physical Features: ectothermic

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 20 years.

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus is primarily found in the low intertidal zone. The purple sea urchin thrives amid strong wave action and areas with churning aerated water. The giant kelp forests provide a feast for S. purpuratus. Many sea urchins can be found on the ocean floor near the holdfast of the kelp. (Calvin et al., 1985; Olhausen and Russo, 1981)

Aquatic Biomes: coastal

Purple sea urchins are found on the pacific coastline from Alaska to Cedros Island, Mexico. (Olhausen and Russo, 1981)

Biogeographic Regions: pacific ocean (Native )

As a sedentary invertebrate, S. purpuratus primarily feeds on algae. Bits of algae are a common food that urchins snag out of the water. The tube feet, spines, and pedicellariae that cover S. purpuratus are used to grab the food and aid it into the mouth. In addition to grabbing food out of the water, S. purpuratus scrapes algae off the rocks or substrate. It's mouth consists of a strong jaw piece called Aristotle's lantern. The mouthpiece itself has five bony teeth that are instrumental in scraping the algae off the substrate. While any algae will satisfy the appetite of the purple sea urchin, this species prefers the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera. (Calvin et al., 1985)

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus is actually used in many seafood recipes. Sea urchin is common in sushi. It is also considered a delicacy in some countries, especially Japan. The primary urchin harvesting company in California sends 75% of the harvest to Japan.The market value for urchins in Japan ranges from $2.20 per tray to $43.00 per tray. In 1994, Japan imported 6, 130 metric tons of sea urchins at a total value of 251 million dollars. Sea urchin harvesting has become one of the highest valued fisheries in California, bringing 80 million dollars in export value per year. (Calvin et al., 1985; Sea Urchin Harvesters Association, 2000)

There is no special status listed for Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. However, the harvest of sea urchins poses some concern for the wellfare of the sea urchin population. As mentioned previously, sea urchins are being exported to Japan and other countries in astounding numbers. This leads some to believe that the populations of sea urchins are drastically declining. The California Department of Fish and Game is trying to control the harvesting of the sea urchin now, to insure that urchin populations do not become endangered. For now, they are simply limiting the number of permits available to fisheries. They are discussing other conservation techniques as well, that have not yet been implimented. (Sea Urchin Harvesters Association, 2000)

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus has adapted the ability to burrow itself into the substrate. In many cases this substrate is rock. Strongylocentrotus purpuratus uses its five bony teeth in concert with its spines to slowly gauge and scrape away at the substrate. The result is a depression in the substrate into which the test of the urchin can settle with a firm hold. The hard surface of the rock or substrate S. purpuratus is scraping does wear out the spines. This does not create a problem since the spines are continually being renewed by growth. This is a unique feature that can sometimes prove deadly. When S. purpuratus is young, it may begin to scrape into the substrate. As it grows, the urchin may find that it has trapped itself for life. As the urchin grew, it gouged out a big enough cavity for its body. However, the initial entrance hole was made when the urchin was much smaller and once grown, it may not be able to retreat from its self-made depression. (Calvin et al., 1985; Olhausen and Russo, 1981; Abbott et al., 1980)

January, February, and March are the primary reproductive months of S. purpuratus. It has been noted, however, that ripe individuals can be found even into the month of July. Purple sea urchins reach sexual maturity at the age of two years. At this time they are about 25mm in diameter or greater. Once sexually mature, females and males release their gametes into the ocean where fertilization occurs. The fertilized egg then settles and begins to grow into an adult. After the egg is fertilized and settles onto a substrate, the urchin begins to develop. The test develops quickly to protect the young urchin. The plates of the test begin to form individually and grow tighter together to form the test. As with most echinoderms, the sexes are usually separate. There is however an occasional hermaphrodite. (Abbott et al., 1980; Calvin et al., 1985; Mead and Denny, 1995)

Breeding interval: Sea urchins breed yearly.

Breeding season: January, February, and March are the primary reproductive months of S. purpuratus.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 2 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 2 years.

Key Reproductive Features: seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); oviparous

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

Sex: male: 730 days.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

Sex: female: 730 days.

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, the purple sea urchin, lives along the eastern edge of the Pacific Ocean extending from Ensenada, Mexico, to British Columbia, Canada.[1] This sea urchin species is deep purple in color, and lives in lower inter-tidal and nearshore sub-tidal communities. Its eggs are orange when secreted in water.[2] January, February, and March function as the typical active reproductive months for the species. Sexual maturity is reached around two years.[3] It normally grows to a diameter of about 10 cm (4 inches) and may live as long as 70 years.[4]

S. purpuratus is used as a model organism and its genome was the first echinoderm genome to be sequenced.[5]

The initial discovery of three distinct eukaryotic DNA-dependent RNA polymerases was made using S. purpuratus as a model organism.[6] While embryonic development is still a major part of the utilization of the sea urchin, studies on urchin's position as an evolutionary marvel have become increasingly frequent. Orthologs to human diseases have led scientists to investigate potential therapeutic uses for the sequences found in Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. For instance, in 2012, scientists at the University of St Andrews began investigating the "2A" viral region in the S. purpuratus genome[7][8] which may be useful for Alzheimer's disease and cancer research. The study identified a sequence that can return cells to a 'stem-cell' like state, allowing for better treatment options.[7] The species has also been a candidate in longevity studies, particularly because of its ability to regenerate damaged or aging tissue. Another study comparing 'young' vs. 'old' suggested that even in species with varying lifespans, the 'regenerative potential' was upheld in older specimens as they suffered no significant disadvantages compared to younger ones.[9]

The genome of the purple sea urchin was completely sequenced and annotated in 2006 by teams of scientists from over 70 institutions including the Kerckhoff Marine Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology as well as the Human Genome Sequencing Center at the Baylor College of Medicine.[10] A new improved version of the purple sea urchin genome, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus v5.0, is now available on Echinobase. S. purpuratus is one of several biomedical research model organisms in cell and developmental biology.[11] The sea urchin is the first animal with a sequenced genome that (1) is a free-living, motile marine invertebrate; (2) has a bilaterally organized embryo but a radial adult body plan; (3) has the endoskeleton and water vascular system found only in echinoderms; and (4) has a nonadaptive immune system that is unique in the enormous complexity of its receptor repertoire.[12]

The sea urchin genome is estimated to encode about 23,500 genes. The S. purpuratus has 353 protein kinases, containing members of 97% of human kinase subfamilies.[13] Many of these genes were previously thought to be vertebrate innovations or were only known from groups outside the deuterostomes. The team sequencing the species concluded that some genes are not vertebrate specific as thought previously, while other genes still were found in the urchin but not the chordate.

The genome is largely non-redundant, making it very comparable to vertebrates, but without the complexity. For example, 200 to 700 chemosensory genes were found that lacked introns, a feature typical of vertebrates.[13] Thus the sea urchin genome provides a comparison to our own and those of other deuterostomes, the larger group to which both echinoderms and humans belong.[12] Sea urchins are also the closest living relative to chordates.[13] Using the strictest measure, the purple sea urchin and humans share 7,700 genes.[14] Many of these genes are involved in sensing the environment,[15] a fact surprising for an animal lacking a head structure.

The sea urchin also has a chemical 'defensome' that reacts when stress is sensed to eliminate potentially toxic chemicals.[13] S. purpuratus's immune systems contains innate pathogen receptors like Toll-like receptors and genes that encode for LRR . There were genes identified for Biomineralization that were not counterparts of the typical human vertebrate variety SCCPs, and encode for transmembrane proteins like P16. Many orthologs exist for genes associated with human diseases, such as Reelin (from Norman-Roberts lissencephaly syndrome) and many cytoskeletal proteins of the Usher syndrome network like usherin and VLGR1.[13]

Increasing carbon dioxide concentrations affect the epigenome, gene expression, and phenotype of the purple sea urchin. Carbon dioxide concentration also reduces the size of its larvae, which indicates that fitness of the larvae could be negatively impacted.[16][17]

The purple sea urchin, along with sea otters and abalones, is a prominent member of the kelp forest community.[18] The purple sea urchin also plays a key role in the disappearance of kelp forests that is currently occurring due to climate change.[19]

Sea urchins like the purple sea urchin have been used for food by the indigenous peoples of California, who ate the yellow egg mass raw.[20][21]

In California, the peak gonad growth season (and therefore peak of edibility) is September–October.[22] Early in the season, the gonads are still growing and the yield will be smaller. From November onwards the gonads are developed, however harvesting stress can induce spawning, decreasing quality.

Oral surface of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus showing teeth of Aristotle's Lantern, spines and tube feet.

Oral surface of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus showing teeth of Aristotle's Lantern, spines and tube feet.  Strongylocentrotus purpuratus

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, the purple sea urchin, lives along the eastern edge of the Pacific Ocean extending from Ensenada, Mexico, to British Columbia, Canada. This sea urchin species is deep purple in color, and lives in lower inter-tidal and nearshore sub-tidal communities. Its eggs are orange when secreted in water. January, February, and March function as the typical active reproductive months for the species. Sexual maturity is reached around two years. It normally grows to a diameter of about 10 cm (4 inches) and may live as long as 70 years.

S. purpuratus is used as a model organism and its genome was the first echinoderm genome to be sequenced.