en

names in breadcrumbs

Choanoflagellatea is ’n klas vrylewende, eensellige en koloniale eukariotiese sweepdiertjies wat beskou word as die naaste lewende verwante aan diere.

Choanoflagellatea is sweepdiertjies met ’n tregtervormige kraag van gekonnekteerde mikrovilli (uitstulpings) aan die basis van elke flagellum (sweephaartjie). Hulle het ’n besonderse selmorfologie wat gekenmerk word deur ’n ronde of ovaal selliggaam van 3 tot 10 µm in deursnee met ’n enkele flagellum aan die punt wat omring word deur ’n kraag van 30 tot 40 mikrovilli (sien skets).

Die beweging van die flagellum skep waterstrome wat die organisme deur die waterkolom stu. So vang hy bakterieë en ander kosbrokkies teen die kraag van mikrovilli vas, waar dit ingeneem word. Hierdie voeding verskaf ’n kritieke skakel binne die globale koolstofkringloop en verbind trofiese vlakke (vlakke in die voedselketting).

Benewens hul belangrike ekologiese rol, is Choanoflagellatea van besondere belang vir evolusionêre bioloë wat die oorsprong van veelselligheid in diere bestudeer. As die naaste lewende verwante aan diere dien Choanoflagellatea as ’n nuttige model vir rekonstruksies van diere se laaste eensellige voorsaat.

Die naam kom van die Griekse woord khoanē, "tregter" (vanweë die vorm van die kraag), en die Latynse woord flagellum.

Hierdie groep is saam met die Ichthyosporea en Filasteria dié eensellige organismes wat die nouste aan die Metazoa (die meersellige diere) verwant is.[1]

OpisthokontaChoanoflagellatea

Choanoflagellatea is ’n klas vrylewende, eensellige en koloniale eukariotiese sweepdiertjies wat beskou word as die naaste lewende verwante aan diere.

Los coanoflagelados (Choanoflagellatea o Choanomonada) son un pequeñu grupu d'eucariotes unicelulares, dacuando coloniales, a los que s'atribúi una gran importancia filoxenética, yá que se supon que son los parientes más próximos de los animales puramente dichos (Metazoos), esto ye, los que formen el reinu Animalia.[2].[1]

La comparanza de xenes y proteínes y l'estudiu de la ultraestructura, dexaron confirmar que los coanoflagelados son evolutivamente falando, el grupu hermanu de los animales verdaderos, faciendo que dellos especialistes incluyir nel reinu Animalia, como'l filu más basal, col nome de Choanomonada en cuenta de incluyilos nel reinu Protista.[3][4]Los coanoflagelados dende esti puntu de vista seríen consideraos los animales más primitivos esistentes.

La principal carauterística d'estos organismos ye la presencia d'un collar o corona formáu por microvellosidades recubiertes de mocu alredor d'un flaxelu; esto los face práuticamente idénticos a los coanocitos de los poríferos (esponxes).

Colonia de Desmarella moniliformis (Craspedida)

Colonia de Codosiga (Craspedida)

Colonia de Sphaeroeca d'aprosimao 230 individuos (Craspedida)

Los coanoflagelados (Choanoflagellatea o Choanomonada) son un pequeñu grupu d'eucariotes unicelulares, dacuando coloniales, a los que s'atribúi una gran importancia filoxenética, yá que se supon que son los parientes más próximos de los animales puramente dichos (Metazoos), esto ye, los que formen el reinu Animalia..

La comparanza de xenes y proteínes y l'estudiu de la ultraestructura, dexaron confirmar que los coanoflagelados son evolutivamente falando, el grupu hermanu de los animales verdaderos, faciendo que dellos especialistes incluyir nel reinu Animalia, como'l filu más basal, col nome de Choanomonada en cuenta de incluyilos nel reinu Protista.Los coanoflagelados dende esti puntu de vista seríen consideraos los animales más primitivos esistentes.

La principal carauterística d'estos organismos ye la presencia d'un collar o corona formáu por microvellosidades recubiertes de mocu alredor d'un flaxelu; esto los face práuticamente idénticos a los coanocitos de los poríferos (esponxes).

Els coanoflagel·lats (Choanoflagellates) són un grup de protozous flagel·lats considerats els éssers morfològicament més semblants animals. Els últims ancestres unicel·lulars dels animals es creu que eren molt semblants als moderns coanoflagel·lats.

Cada coanoflagel·lat té un sol flagel, envoltat per un anell ple d'actina anomenat microvil·li, formant un collar cònic cilíndric. El flagel desplaça l'aigua a través del collar capturant petites partícules d'aliment amb el microvil·lis que són ingerits. Els flagels també permeten nedar a les cèl·lules de manera semblant a com ho fan els espermatozous. Molts coanoflagel·lats construeixen envoltoris en forma de cistella anomenats lorica que està format de silici.

La majoria de coanoflagel·lats són sèssils amb un tall oposat al flagel. Un cert nombre d'espècies, com les del gènere Proterospongia són colonials, normalment prenent la forma de bosses de cèl·lules subjectades per un sol punt, però sovint formant partícules planscòniques amb aparença de raïm amb cada cèl·lula de la colònia flagel·lada.

Els coanòcits (també conegudes com a cèl·lules del collar) dels porífers tenen la mateixa estructura bàsica dels coanoflagel·lats. Es troben ocasionalment en altres grups d'animals com els platihelmints. Aquestes relacions fan dels coanoflagel·lats uns candidats plausibles com a avantpassats representatius del regne animal.

Els coanoflagel·lats (Choanoflagellates) són un grup de protozous flagel·lats considerats els éssers morfològicament més semblants animals. Els últims ancestres unicel·lulars dels animals es creu que eren molt semblants als moderns coanoflagel·lats.

Cada coanoflagel·lat té un sol flagel, envoltat per un anell ple d'actina anomenat microvil·li, formant un collar cònic cilíndric. El flagel desplaça l'aigua a través del collar capturant petites partícules d'aliment amb el microvil·lis que són ingerits. Els flagels també permeten nedar a les cèl·lules de manera semblant a com ho fan els espermatozous. Molts coanoflagel·lats construeixen envoltoris en forma de cistella anomenats lorica que està format de silici.

La majoria de coanoflagel·lats són sèssils amb un tall oposat al flagel. Un cert nombre d'espècies, com les del gènere Proterospongia són colonials, normalment prenent la forma de bosses de cèl·lules subjectades per un sol punt, però sovint formant partícules planscòniques amb aparença de raïm amb cada cèl·lula de la colònia flagel·lada.

Els coanòcits (també conegudes com a cèl·lules del collar) dels porífers tenen la mateixa estructura bàsica dels coanoflagel·lats. Es troben ocasionalment en altres grups d'animals com els platihelmints. Aquestes relacions fan dels coanoflagel·lats uns candidats plausibles com a avantpassats representatius del regne animal.

Choanoflagellater, koanoflagellater eller kraveflagellater er en gruppe encellede eukaryoter, der lever både som fritlevende enkeltceller eller i kolonier overalt i ferskvand, brakvand og saltvand. Choanoflagellaterne anses for at være de nærmeste nulevende encellede slægtninge til dyrene.

Choanoflagellaterne har en enkelt flagel, der har en tragt-formet krave af 30-40 mikrovilli. De har en karakteristisk cellemorfologi kendetegnet ved en ægformet eller kugleformet celle på mindre end 0,01 mm. Bevægelsen af flagellen og fimrehårene medfører fremdriften, og samtidig koncentrerer vandstrømningerne bakterier og andre småting, som bliver indtaget som føde. Genomet indeholder 9.200 gener.

I kraft af choanoflagellaternes globale udbredelse har de stor betydning i naturens husholdning, og de indgår i den marine fødekæde som en stor faktor i det globale kulstofkredsløb.

Choanoflagellaterne er overordentlig interessante fra et evolutionssynspunkt. Hos svampedyrene er der celler, som ser ud præcis som choanoflagellater. Desuden tyder en række molekylærbiologiske DNA-studier på at choanoflagellaterne og dyrene for mellem 600 millioner og 1 milliard år siden udviklede sig fra en fælles stamform. Choanoflagellaterne er dyrenes nærmeste slægtninge. De har gener, der i dyrene

Betydningen for choanoflagellaterne af disse gener og andre ligheder i genomet står hen i det uvisse.

Der er mere end 125 arter af choanoflagellater.

Choanoflagellater, koanoflagellater eller kraveflagellater er en gruppe encellede eukaryoter, der lever både som fritlevende enkeltceller eller i kolonier overalt i ferskvand, brakvand og saltvand. Choanoflagellaterne anses for at være de nærmeste nulevende encellede slægtninge til dyrene.

Choanoflagellaterne har en enkelt flagel, der har en tragt-formet krave af 30-40 mikrovilli. De har en karakteristisk cellemorfologi kendetegnet ved en ægformet eller kugleformet celle på mindre end 0,01 mm. Bevægelsen af flagellen og fimrehårene medfører fremdriften, og samtidig koncentrerer vandstrømningerne bakterier og andre småting, som bliver indtaget som føde. Genomet indeholder 9.200 gener.

Kragengeißeltierchen (Choanomonada, auch Choanoflagellata) sind eine Gruppe einzelliger Lebewesen, die zu den Holozoa gerechnet werden. Durch ihre Ähnlichkeit mit den Kragengeißelzellen (Choanocyten) der Schwämme werden die Choanomonada als die nächsten einzelligen Verwandten der mehrzelligen Tiere angesehen.[1]

Kragengeißeltierchen sind mit Größen von in der Regel bis zu 10 µm vergleichsweise kleine Protisten. Kennzeichnend für sie ist vor allem ein „Kragen“ aus 30 bis 40 feinen, fadenförmigen Zellfortsätzen (Mikrovilli), der in dieser Form bei keiner anderen Protistengruppe existiert, und eine einzelne Geißel in dessen Zentrum, die über den Kragen hinausragt. Eine ehemals wohl vorhandene zweite Geißel ging im Lauf der Entwicklungsgeschichte verloren und lässt sich nur noch am erhalten gebliebenen Kinetosom nachweisen. Die Geißel dient frei schwimmenden Arten wie zum Beispiel Monosiga brevicollis zum Antrieb und festsitzenden Arten wie Codosiga botrytis (syn. Codonosiga botrytis) dazu, eine Strömung zu erzeugen, um Nahrungspartikel den Kragen-Zellfortsetzen zuzuführen. Zwischen Kragen (in der englischsprachigen Fachliteratur collar) und Zellkern befindet sich ein Golgi-Apparat. Das Plasma enthält Mitochondrien. Das Zellende gegenüber der Geißel kann Filipodien tragen oder bei sessilen Arten einen Stiel ausbilden.

Die Gruppe der Acanthoecida bildet eine Lorica, eine korbähnliche Schutzhülle mit rippenartigen, silikathaltigen Verstärkungen.[1] Viele sessile Arten bilden Thecae aus, extrazelluläre, kelch- oder krugförmige, teils gestielte Zellhüllen.

Kragengeißeltierchen kommen entweder als stationäre oder als frei schwebende Individuen bzw. Kolonien im Meer- wie im Süßwasser vor. Es gibt einzellige, frei schwimmende Arten wie Monosiga brevicollis, frei schwimmende Kolonien wie Salpingoeca rosetta und an Substrat fixierte Kolonien wie Codosiga botrytis. Sie schwimmen mit nach hinten gerichter Geißel (Schubgeißel).

Sie ernähren sich von organischen Partikeln, vor allem von im Wasser schwebenden Bakterien und von Viren,[2] die sie fangen, indem sie mit der Bewegung ihrer Geißel diese an ihren Kragen heranstrudeln. Das Wasser mit den Nahrungspartikeln wird von außen nach innen wie in einem Reusenapparat bewegt. Die Bakterien oder sonstigen Teilchen bleiben an der Außenseite der schleimüberzogenen Mikrovilli des Kragenapparates hängen und wandern mit dem Schleim zum Kragenansatz, wo sie in Nahrungsvakuolen transportiert und verdaut werden. Das elektronenmikroskopische Bild rechts unten zeigt einen Kragenflagellaten bei der Aufnahme von Nahrung.

Viele Arten lassen sich leicht kultivieren und haben eine Generationszeit von 6 bis 8 Stunden.[1] Die Vermehrung erfolgt sowohl asexuell als auch sexuell. Am häufigsten ist die asexuelle Vermehrung durch Längsteilung.[3] Bei dem marinen Wimpertierchen Salpingoeca rosetta konnte nachgewiesen werden, dass durch bestimmte Bakterieninhaltsstoffe ein Schwärmen und eine anschließende sexuelle Vermehrung ausgelöst wird.[4]

„Choanovirus“ ist eine vorgeschlagene Gattung von Riesenviren aus dem Phylum Nucleocytoviricota (NCLDV), die Choanoflagellaten der Spezies Bicosta minor (Acanthoecidae) befällt.[5][6] Manche Kragengeißeltierchen ernähren sich jedoch unter anderem von Viren: Julia M. Brown et al. berichteten im September 2020 über den Fund von Virus-DNA in Choanoflagellaten und Picozoen (Picozoa). Bei der gefundenen viralen DNA handelte es sich überwiegend um die von Virophagen (Bakterienviren), also nicht um Viren dieser Einzeller (wie etwa „Choanovirus“) selbst. Da in den Einzellern aber keine Bakterien-DNA gefunden wurde, scheidet auch eine Aufnahme der Virus-DNA als Beifang zusammen mit etwaigen Bakterien aus. Die Autoren gehen daher davon aus, dass die Viren von den Choanoflagellaten als Nahrung aufgenommen wurden. Die Konsequenzen für die marine Ökologie und Fragen zum dadurch möglichen Gentransfer zwischen den Viren und den Einzellern müssen allerdings noch erforscht werden.[7]

Die Kragengeißeltierchen bilden zusammen mit den Vielzelligen Tieren (Metazoa) und einigen Einzellern das Taxon Holozoa:[8]

AmorpheaPilze (Fungi)

Ichthyosporea, Filasterea, Aphelidea, Corallochytrium

Kragengeißeltierchen (Choanoflagellata)

Vielzellige Tiere (Metazoa)

Die Kragengeißeltierchen stellen eine der Gruppen der sogenannten Holozoa dar. Sie wurden traditionell in drei weitere Gruppen unterteilt:[9]

Spätere Forschungsergebnisse führten jedoch durch die Zusammenfassung der Monosigidae und der Salpingoecidae zur Einteilung in nur noch zwei Gruppen:[10]

15 Gattungen

Norris, 1965[11], 31 Gattungen

Ein entscheidender Schritt der Evolution war der Übergang von Einzelzellen zu mehrzelligen Organismen, der sich mehrfach ereignet hat. Höhere Pflanzen, mehrzellige Algen, Pilze und tierische Metazoen haben diesen Schritt vollzogen. Der Übergang zur Mehrzelligkeit der Tiere war besonders markant, weil er den Beginn der sogenannten Kambrischen Explosion[13] markiert, die zur raschen Entstehung der meisten Tierstämme von 530 Millionen Jahren führte. Durch den Vergleich von Proteinen, insbesondere Actin, α-Tubulin, und Elongationsfaktor-la, konnte festgestellt werden, dass sowohl Pilze als auch tierische Metazoen als gemeinsame Vorfahren einen Opisthokonten hatten.[14] Die Analyse von Mitochondrien-DNA zeigte, dass innerhalb der Opisthokonten die Kragengeißeltierchen den Metazoen am nächsten stehen und hier wiederum den Schwämmen.[15] Das legt auch die Morphologie nahe. Das Kragengeißelsystem der Kragengeißeltierchen ist mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit homolog zu dem der Choanozyten der Schwämme (Porifera); dies wird allerdings von einigen Forschern bestritten. Choanoflagellaten und aus Schwammorganismen isolierte Choanozyten sind morphologisch nicht zu unterscheiden. Schwämme und Kragengeißeltierchen bilden also gleichsam eine Brücke zwischen Ein- und Mehrzellern. Der Vergleich der Mitochondrien-DNA zeigt auch, dass Schwämme und Kragengeißeltierchen genetisch gut unterscheidbare Organismengruppen sind und nicht unterschiedliche Manifestationen der gleichen Gruppe. Auch frühere Theorien, die Mehrzelligkeit der Tiere sei mehrfach unabhängig voneinander entstanden, wurde widerlegt, weil keine andere Gruppe von Einzellern irgendeiner Gruppe von tierischen Metazoen näher steht als die Kragengeißeltierchen. Letztere sind also die Schwestergruppe der vielzelligen Tiere, d. h. unter den Einzellern ihre nächsten noch lebenden Verwandten.[15][16]

Kragengeißeltierchen (Choanomonada, auch Choanoflagellata) sind eine Gruppe einzelliger Lebewesen, die zu den Holozoa gerechnet werden. Durch ihre Ähnlichkeit mit den Kragengeißelzellen (Choanocyten) der Schwämme werden die Choanomonada als die nächsten einzelligen Verwandten der mehrzelligen Tiere angesehen.

Choanozoa es un phylo de Opisthokonta, Sarcomastigota.

Holozoa je grupa (kladus) organizama koja obuhvata životinje i njihove najbliže jednoćelijske srodnike, a isključuje gljive.[1][2][3][4]

Holozoa je također i stari naziv roda Distaplia iz grupe Tunikati.[5] Kako su holozoae kladus koji obuhvata sve organizme srodnije životinjama nego gljivama, neki autoriih prepoznaju kao parafiletsku grupu kao što je Choanozoa, koja se uglavnom sastoji od Holozoa, isključujući životinje.[6]

Najpoznatije Holozoa, osim životinja, vjerovatno su hoanoflagelati, koji su veoma slični ćelijama Porifera; čak od 19. stoljeća javljale su se i teorije da su povezani sa sunđerima. Moguće je da je dublje je poznavanje pripadnika roda Proterospongia, kao najupotrebljivijeg primjera kolonijalnih hoanoflagelata, moglo pouzanije proniknuti u porijeklo sunđera. Do prepoznavanja bliskosti ostalih jednoćelijskih holozoa je došlo tokom 1990-tih.[7]

Grupa uglavnom parazitskih vrsta iz oblika zvanih Icthyosporea ili Mesomycetozoea ponekad se grupira zajedno sa drugim vrstama unutar Mesomycetozoa (uočljiva je razliku u sufiksu). Prema strukturi končastih pseudopodija, ameboidni rodovi Ministeria i Capsaspora mogu se spojiti u grupu zvanu Filasterea. Zajedno sa hoanoflagelatima, filasterea su vjerovatno blisko srodni životinjama, a jedna analiza ih je spojila u kladus Filozoa.[3]

Stariji fosili holozoa datiraju unazad do tonijskog perioda, prije oko 970 miliona godina.[8]

Najnoviji kladogram je ukazao na moguće veze i odnose holozoa i ostalih grupa organizama,[9][10]

Ispod je prikazano filogenetsko stablo na bazi multigenske analize iz 2011. Označeno je i prije koliko miliona godina (Mya) je kladus divergirao u nove grane.[11][12][13]

Opisthokonta Holomycota Cristidiscoidea Fungi/ Rozellomyceta/ Cryptomycota Opisthosporidia Holozoa PluriformeaSyssomonas

Filozoa Choanozoa 950 mya 1100 mya 1300 myaAlternativna hipoteza je kladus Teretosporea.

|date= (pomoć) Holozoa je grupa (kladus) organizama koja obuhvata životinje i njihove najbliže jednoćelijske srodnike, a isključuje gljive.

Holozoa je također i stari naziv roda Distaplia iz grupe Tunikati. Kako su holozoae kladus koji obuhvata sve organizme srodnije životinjama nego gljivama, neki autoriih prepoznaju kao parafiletsku grupu kao što je Choanozoa, koja se uglavnom sastoji od Holozoa, isključujući životinje.

Najpoznatije Holozoa, osim životinja, vjerovatno su hoanoflagelati, koji su veoma slični ćelijama Porifera; čak od 19. stoljeća javljale su se i teorije da su povezani sa sunđerima. Moguće je da je dublje je poznavanje pripadnika roda Proterospongia, kao najupotrebljivijeg primjera kolonijalnih hoanoflagelata, moglo pouzanije proniknuti u porijeklo sunđera. Do prepoznavanja bliskosti ostalih jednoćelijskih holozoa je došlo tokom 1990-tih.

Grupa uglavnom parazitskih vrsta iz oblika zvanih Icthyosporea ili Mesomycetozoea ponekad se grupira zajedno sa drugim vrstama unutar Mesomycetozoa (uočljiva je razliku u sufiksu). Prema strukturi končastih pseudopodija, ameboidni rodovi Ministeria i Capsaspora mogu se spojiti u grupu zvanu Filasterea. Zajedno sa hoanoflagelatima, filasterea su vjerovatno blisko srodni životinjama, a jedna analiza ih je spojila u kladus Filozoa.

Χοανόζωα (Choanozoa) (ελληνικά: χόανος + ζῶον) είναι το όνομα συνομοταξίας πρωτίστων που ανήκει στη γενεαλογία των οπισθόκοντων.

Τα περισσότερα φαίνεται να είναι πιο κοντά στα ζώα από ότι στους μύκητες, ενώ έχουν ιδιαίτερο ενδιαφέρον για τους βιολόγους που μελετούν την προέλευση των ζώων.

Η ομοταξία Nucleariida φαίνεται ότι είναι αδελφή ομάδα των μυκήτων, και ως τέτοια συνήθως αποκλείεται από τα Χοανόζωα.[1]

Τα χοανόζωα έχουν περιγραφεί ότι έχουν μία οπίσθια βλεφαρίδα.[2]

Choanozoa

Τα μεγάλα βασίλεια και οι κοντινοί συγγενείς.[3]

Τα χοανόζωα αποτελούνται από τουλάχιστον τρεις ομάδες: (1) τα μεσομυκητόζωα (ή Ιχθυοσπόρεα), ομάδα παρασίτων των ψαριών και άλλων ζώων, (2) μία ομάδα που περιγράφηκε στις αρχές του 21ου αιώνα και περιλαμβάνει τα Ministeria και Capsaspora, η οποία ονομάστηκε νηματύλια (Filasterea) από τα νηματοειδή πλοκάμια που έχουν και τα δύο γένη, και τα χοανομαστιγωτά που περιλαμβάνουν τα γένη Monosiga και Proterospongia.[1][4] The position of Corallochytrium is unclear.[1]

Τα χοανόζωα φαίνεται να είναι παραφυλετική ομάδα από την οποία προήλθαν τα ζώα. Ο Lang 'et al. (2002) προτείνει το νέο όνομα Ολόζωα για μία μονοφυλετική ομαδοποίηση η οποία είναι στην πραγματικότητα τα Χοανόζωα μεγενθυμένα ή επανορισμένα ώστε να περιλαμβάνουν και τα ζώα.[5]

Χοανόζωα (Choanozoa) (ελληνικά: χόανος + ζῶον) είναι το όνομα συνομοταξίας πρωτίστων που ανήκει στη γενεαλογία των οπισθόκοντων.

Τα περισσότερα φαίνεται να είναι πιο κοντά στα ζώα από ότι στους μύκητες, ενώ έχουν ιδιαίτερο ενδιαφέρον για τους βιολόγους που μελετούν την προέλευση των ζώων.

Η ομοταξία Nucleariida φαίνεται ότι είναι αδελφή ομάδα των μυκήτων, και ως τέτοια συνήθως αποκλείεται από τα Χοανόζωα.

Τα χοανόζωα έχουν περιγραφεί ότι έχουν μία οπίσθια βλεφαρίδα.

कीपजन्तु या खोएनोज़ोआ (Choanozoa) (यूनानी: χόανος (choanos) "कीप" and ζῶον (zōon) "प्राणी") पृष्ठध्रुवों की रेखा से संबद्ध सुकेन्द्रिकों के एक संघ का नाम हैं। ऐसा प्रतीत होता हैं कि प्राणियों का उद्गम कीपजन्तुओं में हुआ था, कीपकशाभिकों के सहयोगी क्लेड के रूप में।

The choanoflagellates are a group of free-living unicellular and colonial flagellate eukaryotes considered to be the closest living relatives of the animals. Choanoflagellates are collared flagellates, having a funnel shaped collar of interconnected microvilli at the base of a flagellum. Choanoflagellates are capable of both asexual and sexual reproduction.[8] They have a distinctive cell morphology characterized by an ovoid or spherical cell body 3–10 µm in diameter with a single apical flagellum surrounded by a collar of 30–40 microvilli (see figure). Movement of the flagellum creates water currents that can propel free-swimming choanoflagellates through the water column and trap bacteria and detritus against the collar of microvilli, where these foodstuffs are engulfed. This feeding provides a critical link within the global carbon cycle, linking trophic levels. In addition to their critical ecological roles, choanoflagellates are of particular interest to evolutionary biologists studying the origins of multicellularity in animals. As the closest living relatives of animals, choanoflagellates serve as a useful model for reconstructions of the last unicellular ancestor of animals.

Choanoflagellate is a hybrid word from Greek χοάνηcode: ell promoted to code: el khoánēcode: ell promoted to code: el meaning "funnel" (due to the shape of the collar) and the Latin word flagellum.

Each choanoflagellate has a single flagellum, surrounded by a ring of actin-filled protrusions called microvilli, forming a cylindrical or conical collar (choanoscode: ell promoted to code: el in Greek). Movement of the flagellum draws water through the collar, and bacteria and detritus are captured by the microvilli and ingested.[9] Water currents generated by the flagellum also push free-swimming cells along, as in animal sperm. In contrast, most other flagellates are pulled by their flagella.

In addition to the single apical flagellum surrounded by actin-filled microvilli that characterizes choanoflagellates, the internal organization of organelles in the cytoplasm is constant.[10] A flagellar basal body sits at the base of the apical flagellum, and a second, non-flagellar basal body rests at a right angle to the flagellar base. The nucleus occupies an apical-to-central position in the cell, and food vacuoles are positioned in the basal region of the cytoplasm.[10][11] Additionally, the cell body of many choanoflagellates is surrounded by a distinguishing extracellular matrix or periplast. These cell coverings vary greatly in structure and composition and are used by taxonomists for classification purposes. Many choanoflagellates build complex basket-shaped "houses", called lorica, from several silica strips cemented together.[10] The functional significance of the periplast is unknown, but in sessile organisms, it is thought to aid attachment to the substrate. In planktonic organisms, there is speculation that the periplast increases drag, thereby counteracting the force generated by the flagellum and increasing feeding efficiency.[12]

Choanoflagellates are either free-swimming in the water column or sessile, adhering to the substrate directly or through either the periplast or a thin pedicel.[13] Although choanoflagellates are thought to be strictly free-living and heterotrophic, a number of choanoflagellate relatives, such as members of Ichthyosporea or Mesomycetozoa, follow a parasitic or pathogenic lifestyle.[14] The life histories of choanoflagellates are poorly understood. Many species are thought to be solitary; however, coloniality seems to have arisen independently several times within the group and colonial species retain a solitary stage.[13]

Over 125 extant species of choanoflagellates[9] are known, distributed globally in marine, brackish and freshwater environments from the Arctic to the tropics, occupying both pelagic and benthic zones. Although most sampling of choanoflagellates has occurred between 0 and 25 m (0 and 82 ft), they have been recovered from as deep as 300 m (980 ft) in open water[15] and 100 m (330 ft) under Antarctic ice sheets.[16] Many species are hypothesized to be cosmopolitan on a global scale [e.g., Diaphanoeca grandis has been reported from North America, Europe and Australia (OBIS)], while other species are reported to have restricted regional distributions.[17] Co-distributed choanoflagellate species can occupy quite different microenvironments, but in general, the factors that influence the distribution and dispersion of choanoflagellates remain to be elucidated.

A number of species, such as those in the genus Proterospongia, form simple colonies,[9] planktonic clumps that resemble a miniature cluster of grapes in which each cell in the colony is flagellated or clusters of cells on a single stalk.[10][18] In October 2019, scientists found a new band behaviour of choanoflagellates: they apparently can coordinate to respond to light.[19]

The choanoflagellates feed on bacteria and link otherwise inaccessible forms of carbon to organisms higher in the trophic chain.[20] Even today, they are important in the carbon cycle and microbial food web.[9] There is some evidence that choanoflagellates feast on viruses as well.[21]

Choanoflagellates grow vegetatively, with multiple species undergoing longitudinal fission;[11] however, the reproductive life cycle of choanoflagellates remains to be elucidated. A paper released in August 2017 showed that environmental changes, including the presence of certain bacteria, trigger the swarming and subsequent sexual reproduction of choanoflagellates.[8] The ploidy level is unknown;[23] however, the discovery of both retrotransposons and key genes involved in meiosis[24] previously suggested that they used sexual reproduction as part of their life cycle. Some choanoflagellates can undergo encystment, which involves the retraction of the flagellum and collar and encasement in an electron dense fibrillar wall. On transfer to fresh media, excystment occurs; though it remains to be directly observed.[25]

Evidence for sexual reproduction has been reported in the choanoflagellate species Salpingoeca rosetta.[26][27] Evidence has also been reported for the presence of conserved meiotic genes in the choanoflagellates Monosiga brevicollis and Monosiga ovata.[28]

The Acanthoecid choanoflagellates produce an extracellular basket structure known as a lorica. The lorica is composed of individual costal strips, made of a silica-protein biocomposite. Each costal strip is formed within the choanoflagellate cell and is then secreted to the cell surface. In nudiform choanoflagellates, lorica assembly takes place using a number of tentacles once sufficient costal strips have been produced to comprise a full lorica. In tectiform choanoflagellates, costal strips are accumulated in a set arrangement below the collar. During cell division, the new cell takes these costal strips as part of cytokinesis and assembles its own lorica using only these previously produced strips.[29]

Choanoflagellate biosilicification requires the concentration of silicic acid within the cell. This is carried out by silicon transporter (SiT) proteins. Analysis of choanoflagellate SiTs shows that they are similar to the SiT-type silicon transporters of diatoms and other silica-forming stramenopiles. The SiT gene family shows little or no homology to any other genes, even to genes in non-siliceous choanoflagellates or stramenopiles. This suggests that the SiT gene family evolved via a lateral gene transfer event between Acanthoecids and Stramenopiles. This is a remarkable case of horizontal gene transfer between two distantly related eukaryotic groups, and has provided clues to the biochemistry and silicon-protein interactions of the unique SiT gene family.[30]

Dujardin, a French biologist interested in protozoan evolution, recorded the morphological similarities of choanoflagellates and sponge choanocytes and proposed the possibility of a close relationship as early as 1841.[12] Over the past decade, this hypothesized relationship between choanoflagellates and animals has been upheld by independent analyses of multiple unlinked sequences: 18S rDNA, nuclear protein-coding genes, and mitochondrial genomes (Steenkamp, et al., 2006; Burger, et al., 2003;[14] Wainright, et al., 1993). Importantly, comparisons of mitochondrial genome sequences from a choanoflagellate and three sponges confirm the placement of choanoflagellates as an outgroup to Metazoa and negate the possibility that choanoflagellates evolved from metazoans (Lavrov, et al., 2005). Finally, a 2001 study of genes expressed in choanoflagellates have revealed that choanoflagellates synthesize homologues of metazoan cell signaling and adhesion genes.[31] Genome sequencing shows that, among living organisms, the choanoflagellates are most closely related to animals.[9] Because choanoflagellates and metazoans are closely related, comparisons between the two groups promise to provide insights into the biology of their last common ancestor and the earliest events in metazoan evolution. The choanocytes (also known as "collared cells") of sponges (considered among the most basal metazoa) have the same basic structure as choanoflagellates. Collared cells are found in other animal groups, such as ribbon worms,[32] suggesting this was the morphology of their last common ancestor. The last common ancestor of animals and choanoflagellates was unicellular, perhaps forming simple colonies; in contrast, the last common ancestor of all eumetazoan animals was a multicellular organism, with differentiated tissues, a definite "body plan", and embryonic development (including gastrulation).[9] The timing of the splitting of these lineages is difficult to constrain, but was probably in the late Precambrian,>600 million years ago.[9]

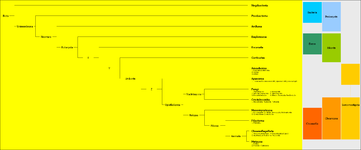

External relationships of Choanoflagellatea.[33]

Opisthokonta Holomycota Holozoa Filozoa ChoanozoaChoanoflagellatea

The choanoflagellates were included in Chrysophyceae until Hibberd, 1975.[34] Recent molecular phylogenetic reconstruction of the internal relationships of choanoflagellates allows the polarization of character evolution within the clade. Large fragments of the nuclear SSU and LSU ribosomal RNA, alpha tubulin, and heat-shock protein 90 coding genes were used to resolve the internal relationships and character polarity within choanoflagellates.[18] Each of the four genes showed similar results independently and analysis of the combined data set (concatenated) along with sequences from other closely related species (animals and fungi) demonstrate that choanoflagellates are strongly supported as monophyletic and confirm their position as the closest known unicellular living relative of animals.

Previously, Choanoflagellida was divided into these three families based on the composition and structure of their periplast: Codonosigidae, Salpingoecidae and Acanthoecidae. Members of the family Codonosigidae appear to lack a periplast when examined by light microscopy, but may have a fine outer coat visible only by electron microscopy. The family Salpingoecidae consists of species whose cells are encased in a firm theca that is visible by both light and electron microscopy. The theca is a secreted covering predominately composed of cellulose or other polysaccharides.[35] These divisions are now known to be paraphyletic, with convergent evolution of these forms widespread. The third family of choanoflagellates, the Acanthoecidae, has been supported as a monophyletic group. This clade possess a synapomorphy of the cells being found within a basket-like lorica, providing the alternative name of "Loricate Choanoflagellates". The Acanthoecid lorica is composed of a series of siliceous costal strips arranged into a species-specific lorica pattern."[10][12]

The choanoflagellate tree based on molecular phylogenetics divides into three well supported clades.[18] Clade 1 and Clade 2 each consist of a combination of species traditionally attributed to the Codonosigidae and Salpingoecidae, while Clade 3 comprises species from the group taxonomically classified as Acanthoecidae.[18] The mapping of character traits on to this phylogeny indicates that the last common ancestor of choanoflagellates was a marine organism with a differentiated life cycle with sedentary and motile stages.[18]

Choanoflagellates;[4]

The genome of Monosiga brevicollis, with 41.6 million base pairs,[9] is similar in size to filamentous fungi and other free-living unicellular eukaryotes, but far smaller than that of typical animals.[9] In 2010, a phylogenomic study revealed that several algal genes are present in the genome of Monosiga brevicollis. This could be due to the fact that, in early evolutionary history, choanoflagellates consumed algae as food through phagocytosis.[36] Carr et al. (2010)[28] screened the M. brevicollis genome for known eukaryotic meiosis genes. Of 19 known eukaryotic meiotic genes tested (including 8 that function in no other process than meiosis), 18 were identified in M. brevicollis. The presence of meiotic genes, including meiosis specific genes, indicates that meiosis, and by implication, sex is present within the choanoflagellates.

The genome of Salpingoeca rosetta is 55 megabases in size.[37] Homologs of cell adhesion, neuropeptide and glycosphingolipid metabolism genes are present in the genome. S. rosetta has a sexual life cycle and transitions between haploid and diploid stages.[27] In response to nutrient limitation, haploid cultures of S. rosetta become diploid. This ploidy shift coincides with mating during which small, flagellated cells fuse with larger flagellated cells. There is also evidence of historical mating and recombination in S. rosetta.

S. rosetta is induced to undergo sexual reproduction by the marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri.[26] A single V. fischeri protein, EroS fully recapitulates the aphrodisiac-like activity of live V. fisheri.

The single-cell amplified genomes of four uncultured marine choanoflagellates, tentatively called UC1–UC4, were sequenced in 2019. The genomes of UC1 and UC4 are relatively complete.[38]

An EST dataset from Monosiga ovata was published in 2006.[39] The major finding of this transcriptome was the choanoflagellate Hoglet domain and shed light on the role of domain shuffling in the evolution of the Hedgehog signaling pathway. M. ovata has at least four eukaryotic meiotic genes.[28]

The transcriptiome of Stephanoeca diplocostata was published in 2013. This first transcriptome of a loricate choanoflagellate[30] led to the discovery of choanoflagellate silicon transporters. Subsequently, similar genes were identified in a second loricate species, Diaphanoeca grandis. Analysis of these genes found that the choanoflagellate SITs show homology to the SIT-type silicon transporters of diatoms and have evolved through horizontal gene transfer.

An additional 19 transcriptomes were published in 2018. A large number of gene families previously thought to be animal-only were found.[40]

Monosiga brevicollis under PCM

Salpingoeca under PCM

Salpingoeca sp. section under TEM

Desmarella moniliformis colony under PCM

Codosiga colony under light microscopy

Sphaeroeca colony (approx. 230 individuals) under light microscopy.

The choanoflagellates are a group of free-living unicellular and colonial flagellate eukaryotes considered to be the closest living relatives of the animals. Choanoflagellates are collared flagellates, having a funnel shaped collar of interconnected microvilli at the base of a flagellum. Choanoflagellates are capable of both asexual and sexual reproduction. They have a distinctive cell morphology characterized by an ovoid or spherical cell body 3–10 µm in diameter with a single apical flagellum surrounded by a collar of 30–40 microvilli (see figure). Movement of the flagellum creates water currents that can propel free-swimming choanoflagellates through the water column and trap bacteria and detritus against the collar of microvilli, where these foodstuffs are engulfed. This feeding provides a critical link within the global carbon cycle, linking trophic levels. In addition to their critical ecological roles, choanoflagellates are of particular interest to evolutionary biologists studying the origins of multicellularity in animals. As the closest living relatives of animals, choanoflagellates serve as a useful model for reconstructions of the last unicellular ancestor of animals.

Los coanoflagelados (Choanoflagellatea o Choanomonada) son un pequeño grupo de eucariotas unicelulares, a veces coloniales, a los que se atribuye una gran importancia filogenética, ya que se supone que son los parientes más próximos de los animales propiamente dichos (Metazoos), esto es, los que forman el reino Animalia.[2] También están relacionados con los hongos verdaderos (reino Fungi), aunque no se los considera sus parientes más cercanos.[1]

La comparación de genes y proteínas y el estudio de la ultraestructura, han permitido confirmar que los coanoflagelados son, evolutivamente hablando, el grupo hermano de los animales verdaderos, haciendo que algunos especialistas los incluyan en el reino Animalia, como el filo más basal, con el nombre de Choanomonada o Choanozoa en vez de incluirlos en el reino Protista. [3][4]

La principal característica de estos organismos es la presencia de un collar o corona formado por microvellosidades recubiertas de moco alrededor de un flagelo; esto los hace prácticamente idénticos a los coanocitos de los poríferos (esponjas).

Los coanoflagelados constituyen un grupo no muy diverso, consistente en unas 150 especies repartidas entre unos 50 géneros en dos órdenes.[1] Habitan todos los ambientes acuáticos, aunque su presencia es más notable en los mares fríos y polares. Filtran el agua para separar sobre todo bacterias, que es su alimento básico.

En su morfología hay varios rasgos peculiares. Muestran una marcada polaridad celular. Presentan un polo de fijación o pedúnculo, por el que se pueden unir al sustrato. El otro polo de movilidad o kinético, aparece típicamente envuelto por una lorica, de microtúbulos con el aspecto de una jaula laxamente trenzada. En este mismo polo kinético la abertura de la célula aparece circundada por un collar de microvellos con forma de copa, desde cuyo centro surge un solo flagelo, que se agita con un movimiento helicoidal.[5]

Un examen con microscopía electrónica muestra que el collar, que parece continuo con menos ampliación, está en realidad constituido por una corona de microvellosidades (microvilli), delgados apéndices con forma de dedo.

Los coanoflagelados pueden ser encontrados como nadadores libres en la columna de agua o sésiles, adhiriéndose al sustrato directamente o por medio del periplasto.

Su ciclo de vida aún no ha sido aclarado. Por el momento, no se sabe si existe una fase sexual en su ciclo. Algunos coanoflagelados pueden formar quistes.[6]

Desde un principio llamó la atención la semejanza de la anatomía de los coanoflagelados y la de las células filtradoras de las esponjas, los coanocitos. Algunos coanoflagelados forman colonias, que en el caso de los géneros Spongomonas o Proterospongia forman un conjunto bastante organizado, con cierta especialización de las células que hace pensar en una pequeña esponja extremadamente sencilla. Los coanoflagelados nos permiten hacernos una idea de como empezó la evolución de algunos organismos pluricelulares (reinos Animalia y Fungi) a partir de los protistas.

Como los espermatozoides de los animales, los coanoflagelados son opistocontos, es decir, el flagelo impulsa a la célula hacia adelante, avanzando con el flagelo detrás, al revés que la mayoría de los protistas, que son acrocontos (el flagelo arrastra la célula, que avanza con él por delante). Es uno de los detalles que permiten unir a los animales (y coanoflagelados) con los hongos en un grupo mayor llamado Opisthokonta (opistocontos), como puede comprobarse en el siguiente cladograma:[7][8][9]

Opisthokonta Holomycota Holozoa Filozoa ApoikozoaChoanoflagellatea

Colonia de Desmarella moniliformis (Craspedida)

Colonia de Codosiga (Craspedida)

Colonia de Sphaeroeca de aproximadamente 230 individuos (Craspedida)

Los coanoflagelados (Choanoflagellatea o Choanomonada) son un pequeño grupo de eucariotas unicelulares, a veces coloniales, a los que se atribuye una gran importancia filogenética, ya que se supone que son los parientes más próximos de los animales propiamente dichos (Metazoos), esto es, los que forman el reino Animalia. También están relacionados con los hongos verdaderos (reino Fungi), aunque no se los considera sus parientes más cercanos.

La comparación de genes y proteínas y el estudio de la ultraestructura, han permitido confirmar que los coanoflagelados son, evolutivamente hablando, el grupo hermano de los animales verdaderos, haciendo que algunos especialistas los incluyan en el reino Animalia, como el filo más basal, con el nombre de Choanomonada o Choanozoa en vez de incluirlos en el reino Protista.

La principal característica de estos organismos es la presencia de un collar o corona formado por microvellosidades recubiertas de moco alrededor de un flagelo; esto los hace prácticamente idénticos a los coanocitos de los poríferos (esponjas).

Taksonoomia Domeen Eukarüoodid Eukaryota Jagu Opisthokonta Hõimkond Choanozoa Klass Kaelusflagellaadid Choanoflagellatea

Taksonoomia Domeen Eukarüoodid Eukaryota Jagu Opisthokonta Hõimkond Choanozoa Klass Kaelusflagellaadid Choanoflagellatea Kaelusviburlased ehk kaelusflagellaadid (Choanoflagellatea, Choanoflagellata, Choanomonada, varasema nimega Craspedophyceae) on väike rühm viburiga protiste. Neid peetakse fülogeneetiliselt lähimateks sugulasteks loomadele (loomariigile). Kaelusflagellaadid elavad nii mere- kui magevees. Kaelusflagellaate on teada umbes 150 liiki.

Kõikidel kaelusflagellaatidel on üks vibur. Viburiga tekitavad nad vees rakupoolse keerise, mis tagab toiduosakeste jõudmise rakupinnale (kaelustele). Toit neelatakse alla pseudopoodidega.

Süstemaatikas jagatakse kaelusflagellaadid kolme rühma, mida käsitletakse sugukonna tasemel:

Kaelusviburlased ehk kaelusflagellaadid (Choanoflagellatea, Choanoflagellata, Choanomonada, varasema nimega Craspedophyceae) on väike rühm viburiga protiste. Neid peetakse fülogeneetiliselt lähimateks sugulasteks loomadele (loomariigile). Kaelusflagellaadid elavad nii mere- kui magevees. Kaelusflagellaate on teada umbes 150 liiki.

Kõikidel kaelusflagellaatidel on üks vibur. Viburiga tekitavad nad vees rakupoolse keerise, mis tagab toiduosakeste jõudmise rakupinnale (kaelustele). Toit neelatakse alla pseudopoodidega.

Choanoflagellata eukarioto flagelatu aske zelulabakar kolonialak dira, ziurrenik animalien ahaiderik gertukoenak. Izenak berak dioen bezala lepodoa duten flagelatuak dira eta zelula distintiboa dute, 3-10 µm arteko diametroko oboide esferikoa flagelo apilak bakar batekin. Lepoko horrek 30-40 mikrobilo ditu. Flageloaren mugimenduek ur korronteak sortzen ditu eta konoflagelatua mugit daiteke, bakteria eta detritusak irensteko. Ekologikoki oso garrantzitsuak dira, karbonoaren zikloan duten papera dela eta.

Kaulussiimaeliöt[3] eli choanoflagellaatit (Choanoflagellida, Choanoflagellata) on mikroskooppisten siimaeliöiden pääjakso tai luokka. Jotkut lajit ovat yksittäisiä soluja, toiset ovat monisoluisia. Niillä ei ole viherhiukkasia, ja ovat toisenvaraisia. Jotkut uskovat niiden muodostavan eläinkunnan yksinkertaisimman pääjakson; toiset pitävät niitä alkueliöinä.[4][5]

Kaulussiimaeliöt eli choanoflagellaatit (Choanoflagellida, Choanoflagellata) on mikroskooppisten siimaeliöiden pääjakso tai luokka. Jotkut lajit ovat yksittäisiä soluja, toiset ovat monisoluisia. Niillä ei ole viherhiukkasia, ja ovat toisenvaraisia. Jotkut uskovat niiden muodostavan eläinkunnan yksinkertaisimman pääjakson; toiset pitävät niitä alkueliöinä.

Les Choanoflagellés, Choanoflagellata ou Choanomonada, sont un petit groupe d’eucaryotes opisthocontes unicellulaires proches des métazoaires. Ces protistes flagellés ont un mode de vie colonial et non-fixé (vivant en pleine eau) ou pour certaines espèces sont associés au périphyton.

On en connait plus de 125 espèces, largement réparties et souvent abondantes. L'inventaire n'en est peut-être pas exhaustif.

Parmi les microorganismes, ils sont considérés comme étant les plus proches parents vivants des premiers animaux et à ce titre sont utilisés par les biologistes évolutionnistes et la biologie évolutive du développement comme modèle pour les reconstructions du dernier ancêtre des animaux unicellulaires. Certains processus biochimiques observés dans notre cerveau pourraient directement dériver de ceux qui sont observés chez les Choanoflagellés[2].

Bien que discrets, ils sont très présents dans les océans où ils jouent un rôle important dans les cycles biogéochimiques et en particulier pour le cycle du carbone et le cycle de la silice.

Les traits de vie des Choanoflagellés sont encore mal compris. Beaucoup d'espèces sont supposées solitaires, mais des comportements coloniaux semblent avoir surgi indépendamment et à plusieurs reprises au sein du groupe (mais les espèces coloniales conservent un stade initial solitaire)[3].

La cellule mesure de 3 à 10 µm et se caractérise par :

Les Choanoflagellés nagent librement dans la colonne d'eau ou sont sessiles (ils adhèrent alors directement au substrat ou par l'intermédiaire du périplasme ou d'un mince pédoncule[7].

Selon les connaissances actuellement disponibles, les Choanoflagellés semblent mener une vie toujours hétérotrophe sans directement dépendre d'une autre espèces, mais un certain nombre de parents des Choanoflagellés tels que certains Ichthyosporea ou Mesomycetozoa ont au cours de l'évolution adopté un mode de vie parasitaire ou sont des pathogènes d'autres espèces[8].

Contrairement aux plantes et aux champignons ce groupe se montre capable de former des colonies motile et pouvant se déformer via l'activation collective d'une contractilité (chez les animaux pluricelullaire, la contractilité collective de groupes de cellules est à la base de nombreux processus (ex gastrulation, ingestion, excrétion, réflexion de fuite, motilité musculaire, etc.

Brunet et al. décrivent en 2019 un choanoflagellé récemment découvert (Choanoeca flexa sp. Nov.), qui forme des colonies en forme de coupe (formée d'une monocouche de cellules polarisées) ; ces colonies sont capables de contractilité et de comporement alimentaire collective, mais aussi de changement rapide de morphologie en réponse à une soudaine privation de lumière (la colonie inverse alors son sens de courbure, grâce à une protéine photosensible). Les auteurs notent que les mécanismes cellulaires qui président à ce processus sont les mêmes chez C. flexa et chez les animaux, ce qui évoque un dernier ancêtre commun déjà capable de contracter des cellules polarisées[9].

les Choanoflagellés ont une croissance végétative, avec pour de nombreuses espèces une reproduction par fission longitudinale[4]. Le cycle de la vie reproductive des Choanoflagellés reste cependant encore incompris. On ignore encore s'il existe aussi une phase sexuelle dans le cycle de vie de ce groupe. Son niveau de ploïdie est également inconnu[4],[10]

La reproduction sexuée n'a pas encore été observée, mais deux rétrotransposons et des gènes clés impliqués dans la méiose ont été découverts dans leur génome[11] suggérant une possible sexualité.

Certains choanoflagellés peuvent s'enkyster (avec perte du flagelle et du collier)[12].

Les Choanoflagellés sont planctoniques ou fixés sur des algues (périphyton).

On les rencontre principalement en milieu marin, de répartition mondiale puisque dans tous les océans. Certaines espèces sont cependant dulçaquicoles (d'eau douce).

Leur nourriture semblaient essentiellement constituée de bactéries, mais des chercheurs ont récemment montré que - au moins dans certaines zones du monde (par exemple dans le Golfe de Gabès sur la côte est de la Tunisie) - ils pouvaient aussi « brouter » de grandes quantités de nanophytoplancton[13].

Le système digestif est rudimentaire, constitué de simples vacuoles alimentaires positionnées dans la partie basale du cytoplasme[5],[4].

Les particules alimentaires (bactéries, microalgues) sont apportées aux vacuoles digestives grâce à un mouvement du flagelle entraînant le déplacement de l'eau qui crée une dépression sur les bords de la collerette, qui conduit à une aspiration de l'eau apportant des bactéries au niveau de la collerette, alimentant ainsi la cellule qui peut les ingérer.

Les Choanoflagellés Acanthoecidae produisent une structure extracellulaire dite lorica (du nom d'une armure romaine faite de bandes). Cette structure est composée de bandes individuelles formées d'un biocomposite (une sorte de polymère composé de silice et de protéines). le matériau de chacune de ces bandes est synthétisé à l'intérieur de la cellule puis excrétée à l'extérieur, sur la surface de la cellule.

Chez les Choanoflagellés « nudiformes », l'assemblage de ces bandes se fait grâce à un certain nombre de petits tentacules. Elles sont produites par la cellule jusqu'à ce que la lorica soit entièrement réalisée.

Chez les Choanoflagellés dits tectiformes, des bandes costales sont produites en excès et s'accumulent dans une zone situé sous le col. Quand la cellule-mère se divise pour produire une cellule fille, la nouvelle cellule capte une partie de ces bandes dans le cadre de la cytokinèse et assemble sa propre lorica (en n'utilisant que les bandes siliceuses produites précédemment)[14]

La biosilicification n'est possible que si de la silice (en l’occurrence sous forme d'acide silicique) a été préalablement bioconcentrée dans la cellule, ce qui est possible grâce à des protéines transporteuses dédiées dites « SIT » (pour « Silicon Transporter »).

L'étude de ces protéines SIT a montré qu'elles étaient similaires à celles trouvées chez les diatomées et d'autres straménopiles biosynthétisant également des squelettes siliceux, cependant la famille des gènes codant la protéine SIT ne montre que peu ou pas d'homologie avec les autres gènes des Choanoflagellés, y compris de Choanoflagellés non-siliceux ou des straménopiles. Ceci suggère que la famille des gènes de SIT a évolué ailleurs et qu'il y a eu un événement de transfert de gène entre Acanthoecidae et straménopiles. C'est un cas remarquable de transfert horizontal de gènes entre deux groupes eucaryotes lointainement apparentés[15]

Les Choanoflagellés, Choanoflagellata ou Choanomonada, sont un petit groupe d’eucaryotes opisthocontes unicellulaires proches des métazoaires. Ces protistes flagellés ont un mode de vie colonial et non-fixé (vivant en pleine eau) ou pour certaines espèces sont associés au périphyton.

On en connait plus de 125 espèces, largement réparties et souvent abondantes. L'inventaire n'en est peut-être pas exhaustif.

Parmi les microorganismes, ils sont considérés comme étant les plus proches parents vivants des premiers animaux et à ce titre sont utilisés par les biologistes évolutionnistes et la biologie évolutive du développement comme modèle pour les reconstructions du dernier ancêtre des animaux unicellulaires. Certains processus biochimiques observés dans notre cerveau pourraient directement dériver de ceux qui sont observés chez les Choanoflagellés.

Bien que discrets, ils sont très présents dans les océans où ils jouent un rôle important dans les cycles biogéochimiques et en particulier pour le cycle du carbone et le cycle de la silice.

Les traits de vie des Choanoflagellés sont encore mal compris. Beaucoup d'espèces sont supposées solitaires, mais des comportements coloniaux semblent avoir surgi indépendamment et à plusieurs reprises au sein du groupe (mais les espèces coloniales conservent un stade initial solitaire).

Os coanozoos (Choanozoa, do grego χόανος chóanos, "embude" e ζῶον zōon, "animal") é un filo de protistas relacionado cos animais e cos fungos.

En efecto, baseándose en estudos moleculares, os Choanozoa inclúense no supergrupo de eucariontes denominado Opisthokonta xunto cos Animalia e os Fungi.[1] [2]

Un sinónimo de Choanozoa é Mesomycetozoa, que significa "entre fungos e animais",[3] pero non debe confundirse con Mesomycetozoea, que é unha clase.

O nome Opisthokonta (opistocontos) alude a que o flaxelo, único cando está presente, ocupa unha posición posterior, avanzando a célula co flaxelo detrás, como se observa nos espermatozoides dos animais e ao revés que na maioría dos protistas, que son acrocontos (levan o flaxelo no extremo dianteiro). Isto é un dos detalles que permiten unir aos animais, os coanozoos e os fungos nun grupo maior (os opistocontos) como pode comprobarse no cladograma que vai ao final deste texto

O filo dos Choanozoa inclúe unha colección diversa de protistas que se clasifican en varias clases.

Delas destaca Choanoflagellata, que comprende unhas 150 especies que viven en augas doces e mariñas e que presentan un colar de microvilosidades que rodea o único flaxelo e do cal toman o nome.

Os coanoflaxelados son case idénticos en forma e función aos coanocitos das Porifera (esponxas), os animais actuais máis primitivos, polo que os coanoflaxelados (e os Ministeriida) parecen estar moi relacionados co reino animal.

Porén, as clases dos Corallochytrea e os Mesomycetozoea parecen estar no límite entre os fungos e os animais.

A clase dos Mesomycetozoea ou Ichthyosporea comprende especies parasitas de vertebrados, principalmente de peixes, aparecendo nos tecidos do hóspede como esferas ou óvalos que conteñen esporas.

A clase dos Corallochytrea inclúe un único organismo, Corallochytrium limacisporum, mariño e saprófito.

As clases dos Nucleariida e os Ministeriida antigamente se clasificaban xuntas na clase dos Cristidiscoidea, pero esta resultou ser polifilética, como o demostran diversos estudos de árbores filoxenéticas.

A clase dos Nucleariida comprende un pequeno grupo de ameboides con pseudópodos filiformes (filopodios), que viven principalmente no solo e en auga doce, e son a miúdo parasitos.

A clase dos Ministeriida inclúe a un protista mariño radiado e non flaxelado. Os Nucleariida parecen estaren relacionados cos fungos e os Ministeriida cos animais.

No pasado incluíranse tamén entre os protistas aos Chytridiomycota, pero agora se clasifican entre os fungos.

Os coanozoos permiten facernos unha idea de como empezou a evolución dos verdadeiros animais pluricelulares (reino dos Animalia) a partir dos protistas. De feito, a comparación de xenes e proteínas e o estudo da ultraestrutura permitiron confirmar que un dos grupos dos coanozoos, os coanoflaxelados son, evolutivamente falando, o grupo irmán dos animais verdadeiros. Algúns especialistas tenden ultimamente a incluílos no reino animal, como o filo máis basal, dándolle o nome de Choanozoa (coanozoos), en lugar de incluílos no reino dos protistas.

Os coanozoos (Choanozoa, do grego χόανος chóanos, "embude" e ζῶον zōon, "animal") é un filo de protistas relacionado cos animais e cos fungos.

En efecto, baseándose en estudos moleculares, os Choanozoa inclúense no supergrupo de eucariontes denominado Opisthokonta xunto cos Animalia e os Fungi.

Un sinónimo de Choanozoa é Mesomycetozoa, que significa "entre fungos e animais", pero non debe confundirse con Mesomycetozoea, que é unha clase.

O nome Opisthokonta (opistocontos) alude a que o flaxelo, único cando está presente, ocupa unha posición posterior, avanzando a célula co flaxelo detrás, como se observa nos espermatozoides dos animais e ao revés que na maioría dos protistas, que son acrocontos (levan o flaxelo no extremo dianteiro). Isto é un dos detalles que permiten unir aos animais, os coanozoos e os fungos nun grupo maior (os opistocontos) como pode comprobarse no cladograma que vai ao final deste texto

Choanozoa, jednočelijski kolonijalni organizmi sa oko 150 vrsta. Naseljavaju mora i slatke vode. Klasificirani su kao koljeno Opisthokonta. Još uvijek nije dobro proučena citološka organizacija i genetička struktura nekih razreda. Hrane se fagotrofno a neke vrste posjeduju zelene kromoplaste za fotosintezu.

Choanozoa, jednočelijski kolonijalni organizmi sa oko 150 vrsta. Naseljavaju mora i slatke vode. Klasificirani su kao koljeno Opisthokonta. Još uvijek nije dobro proučena citološka organizacija i genetička struktura nekih razreda. Hrane se fagotrofno a neke vrste posjeduju zelene kromoplaste za fotosintezu.

Choanoflagellatea adalah grup eukariota berflagel bersel satu atau berkoloni yang hidup bebas yang dianggap sebagai keluarga terdekat binatang. Seperti yang dikesankan namanya, Choanoflagellatea (yang berarti: flagellata berkerah) memiliki morfologi sel yang khas yang bercirikan tubuh sel yang berbentuk oval atau membulat berdiameter 3-10 µm dengan sebuah flagel pucuk yang dikelilingi oleh kerah dari 30-40 mikrovili (lihat gambar). Gerakan flagel itu menimbulkan aliran air yang dapat mendorong Choanoflagellatea yang berenang bebas melewati air dan menjebak bakteri dan detritus menuju kerah dari mikrovili itu di mana makanan itu ditelan. Kegiatan makan ini menyediakan hubungan kritis dalam siklus karbon global, menghubungkan level trofik. Selain peran ekologis mereka yang kritis, Choanoflagellatea merupakan perhatian istimewa bagi biolog evolusioner yang mempelajari asal mula kemultiseluleran pada binatang. Sebagai keluarga yang terdekat dari binatang, Choanoflagellatea berperan sebagai model yang berguna bagi rekonstruksi moyang bersel satu paling muda dari binatang.

Setiap Choanoflagellatea memiliki sebuah flagel, yang dikelilingi oleh cincin dari tonjolan-tonjolan berisi aktin yang disebul mikrovili, membentuk kerah yang bentuknya silindris atau mengerucut (choanos dalam bahasa Yunani). Gerakan flagel itu menarik air melewati kerah itu, dan bakteri serta detritus ditangkap oleh mikrovili itu dan ditelan.[6] Aliran air yang ditimbulkan oleh flagel itu juga mendorong sel-sel yang bersel satu pada saat yang sama, seperti pada sperma binatang. Kontras dengan itu, kebanyakan flagellata lain ditarik oleh flagel mereka.

Selain flagel apikal tungal yang dikelilingi oleh mikrovili berisi aktin yang mencirikan Choanoflagellatea, organisasi internal dari organel-organel di sitoplasmanya konstan[7]. Badan basal flagel berada di dasar flagel apikalnya, dan yang kedua, badan basal non-flagel menempati posisi apikal-ke-pusat di selnya, dan vakuola makanannya berada di daerah basal dari sitoplasma itu.[7][8] Selain itu, badan sel banyak Choanoflagellatea diselimuti oleh matriks ekstraseluler atau periplas yang khas. Penutup-penutup sel ini sangat beragam struktur dan komposisinya dan digunakan oleh para taksonom untuk tujuan klasifikasi. Banyak Choanoflagellatea membuat "rumah" berbentuk keranjang yang rumit yang disebut lorika, yang terbuat dari beberapa potongan silika yang dilekatkan bersama-sama.[7] Peran fungsional dari periplas tidak diketahui, tetapi pada organisme sesil, periplas itu dianggap membantu menempel pada substratnya. Pada organisme-organisme planktonik, ada spekulasi bahwa periplas itu meningkatkan hambatan dan karenanya berlawanan dengan gaya yang ditimbulkan oleh flagel dan meningkatkan efisiensi makan.[9] Choanoflagellatea bisa berenang bebas dalam air bisa pula sesil, menempel pada substratnya secara langsung atau bisa melalui periplas atau pedisel kecil.[10] Meskipun Choanoflagellatea dianggap benar-benar hidup bebas dan heterotrof, beberapa keluarga dari Choanoflagellatea seperti anggota Ichthyosporea atau Mesomycetozoa hidup sebagai parasit atau patogen.[11] Sejarah hidup Choanoflagellatea sedikit diketahui. Banyak spesies dianggap soliter; namun kehidupan berkoloni tampaknya muncul secara mandiri beberapa kali dalam grup itu dan spesies yang berkoloni mempertahankan tahap hidup soliter.[10]

Choanoflagellatea tumbuh secara vegetatif, dengan banyak spesies mengalami pembelahan fisi logitudinal[8]; namun demikian, daur hidup reproduktif Choanoflagellatea masih perlu diperjelas. Saat ini, tidak jelas apakan ada fase seksual pada daur hidup Choanoflagellatea. Yang menarik, beberapa Choanoflagellatea dapat membentuk kista, yang melibatkan ditariknya flagel dan kerahnya dan pembungkusan dalam dinding fibrilar yang rapat dengan elektron. Bila berpindah ke media yang segar, maka ia keluar dari kista, meski itu perlu diamati secara langsung[12]. Pemeriksaan lebih jauh terhadap daur hidup Choanoflagellatea akan lebih informatif tentang mekanisme pembentukan koloni dan atribut yang ada sebelum evolusi dari kemultiseluleran binatang.

Sejumlah spesies seperti yang bergenus Proterospongia membentuk koloni,[6] gumpalan planktonik yang mirip dompolan anggur kecil di mana tiap sel dalam koloni itu berflagel atau kumpulan sel-sel pada batang tunggal.[13][7]

Ada lebih dari 125 spesies Choanoflagellatea yang hidup,[6] tersebar secara global di lingkungan laut, air payau dan air tawar dari Arktika hingga ke daerah tropis, menempati zona pelagis dan bentik. Meskipun kebanyakan pengambilan sampel Choanoflagellatea berasal dari kedalaman 0 hingga 25 meter, mereka telah ditemukan hingga sedalam 300 meter di perairan terbuka[14] dan 100 m di bawah lapisan es Antartika.[15] Banyak spesies dihipotesiskan kosmpolitan dalam skala global [contohnya, Diaphanoeca grandis dilaporkan dari Amerika Utara, Eropa, Australia (OBIS)], sedangkan spesies lain dilaporkan penyebarannya terbatas di suatu daerah.[16] spesies Choanoflagellatea yang tersebar bersama-sama menempati mikrolingkungan yang cukup berbeda, tetapi umumnya, faktor-faktor yang memengaruhi penyebaran itu masih perlu diperjelas.

|coauthors= yang tidak diketahui mengabaikan (|author= yang disarankan) (bantuan) |coauthors= yang tidak diketahui mengabaikan (|author= yang disarankan) (bantuan) |doi= (bantuan). Parameter |coauthors= yang tidak diketahui mengabaikan (|author= yang disarankan) (bantuan) |coauthors= yang tidak diketahui mengabaikan (|author= yang disarankan) (bantuan) |coauthors= yang tidak diketahui mengabaikan (|author= yang disarankan) (bantuan) |coauthors= yang tidak diketahui mengabaikan (|author= yang disarankan) (bantuan) |doi= (bantuan). |doi= (bantuan). Parameter |coauthors= yang tidak diketahui mengabaikan (|author= yang disarankan) (bantuan) |coauthors= yang tidak diketahui mengabaikan (|author= yang disarankan) (bantuan) Choanoflagellatea adalah grup eukariota berflagel bersel satu atau berkoloni yang hidup bebas yang dianggap sebagai keluarga terdekat binatang. Seperti yang dikesankan namanya, Choanoflagellatea (yang berarti: flagellata berkerah) memiliki morfologi sel yang khas yang bercirikan tubuh sel yang berbentuk oval atau membulat berdiameter 3-10 µm dengan sebuah flagel pucuk yang dikelilingi oleh kerah dari 30-40 mikrovili (lihat gambar). Gerakan flagel itu menimbulkan aliran air yang dapat mendorong Choanoflagellatea yang berenang bebas melewati air dan menjebak bakteri dan detritus menuju kerah dari mikrovili itu di mana makanan itu ditelan. Kegiatan makan ini menyediakan hubungan kritis dalam siklus karbon global, menghubungkan level trofik. Selain peran ekologis mereka yang kritis, Choanoflagellatea merupakan perhatian istimewa bagi biolog evolusioner yang mempelajari asal mula kemultiseluleran pada binatang. Sebagai keluarga yang terdekat dari binatang, Choanoflagellatea berperan sebagai model yang berguna bagi rekonstruksi moyang bersel satu paling muda dari binatang.

I coanoflagellati sono un gruppo di protisti flagellati, precedentemente classificati nel gruppo polifiletico dei protozoi. Etimologicamente possono essere considerati gli "unici veri protozoi", dal momento che sono i parenti più vicini ai metazoi: gli antenati unicellulari degli animali apparivano probabilmente simili ai moderni coanoflagellati.

Ogni coanoflagellato ha un singolo flagello, circondato da un anello di protrusioni formate da actina chiamate microvilli, che formano un collare (χόανος, chóanos in greco antico). Il flagello tira l'acqua attraverso il collare e piccole porzioni di cibo sono catturate dai microvilli e ingerite. Il flagello spinge anche le cellule, come negli spermatozoi, mentre altre cellule flagellate sono tirate dai flagelli posti in posizione anteriore. Il collare dei coanoflagellati è virtualmente identico ai coanociti della spugne. Alla base del collaretto vi è un piccolo pseudopodio che serve a fagocitare le prede raccolte nel collaretto. Presentano un glicocalice che può essere spesso e formare una teca; in alcuni presentano spicole o scaglie silicee. La riproduzione avviene in primavera ed estate, quando cellule riproduttive diploidi specializzate si dividono per formare una nuova colonia figlia, che rimane nella colonia madre finché non ha raggiunto le dimensioni idonee per fuoriuscire. La riproduzione sessuale avviene principalmente in autunno, con lo sviluppo di cellule sessuali aploidi. Lo zigote può incistarsi per passare l'inverno e poi svilupparsi in una colonia asessuale matura in primavera. In alcune specie le colonie hanno sessi separati; in altre sia le uova sia gli spermi sono prodotti dalla stessa colonia.

Choanoflagellata of Choanomonada zijn een groep van de protozoa met één flagel. Met andere woorden; het zijn eencellige micro-organismen (eukaryoten) met een staart. Deze staart is omringd door microvilli. Zij zijn cilindervormig (χοάνη, choanē is Oudgrieks voor "koker").

De choanoflagellata zijn een groep organismen die heel dicht bij de dieren staan in de evolutionaire geschiedenis, en ermee gegroepeerd zitten als Holozoa.

Stamboom van de dieren binnen de UnikontaStamboom van de dieren binnen de Unikonta

Wiciowce kołnierzykowe (Choanoflagellata) – jednokomórkowe, jednojądrowe, wodne, wolno żyjące organizmy eukariotyczne wyposażone w pojedynczą, długą wić otoczoną podobnym do choanocytu gąbek wysokim kołnierzykiem z wypustek cytoplazmatycznych (microvilli), tworzącym rodzaj aparatu filtrującego.

Wiciowce kołnierzykowe są organizmami cudzożywnymi, żyjącymi pojedynczo lub kolonijnie w słonych i słodkich wodach całego świata. Większość z dotychczas opisanych gatunków występuje w strefie pelagialnej lub bentalnej mórz i oceanów, a około 50 gatunków w wodach słodkich. Odżywiają się bakteriami, które są odfiltrowywane z pomocą wspomnianego kołnierzyka. Ich cykl życiowy pozostaje słabo poznany. Tradycyjnie zaliczane były do wiciowców (Flagellata). Są blisko spokrewnione z wielokomórkowcami (Metazoa).

Interesującą cechą budowy komórki tych wiciowców jest obecność dodatkowego ciałka podstawowego leżącego w pobliżu ciałka podstawowego wici. Wiciowce kołnierzykowe rozmnażają się bezpłciowo.

Termin Choanoflagellata został wprowadzony przez Williama Saville-Kenta w 1880. Klasyfikacja biologiczna tej grupy organizmów przez długi czas pozostawała niejasna. Zaliczano je w randze klasy Choanoflagellatea do grzybów (Fungi) lub do typu Choanozoa, w randze typu do protistów (Protista) lub Protozoa. Na podstawie badań genetycznych uznane zostały za klad należący do Opisthokonta. Obecność wici oraz podobieństwo do choanocytów skłaniało wielu badaczy (w tym Buck, 1990, Hausmann i Hülsmann, 1996 oraz Cavalier-Smith, 1987 i 1998) do postawienia hipotezy, że kolonijne Choanoflagellata mogły być przodkami zwierząt wielokomórkowych i grzybów. Sugerowały to również wyniki badania niektórych genów – stwierdzono, że u tych wiciowców występują geny niezbędne do sygnalizacji międzykomórkowej, czyli odpowiedzialne za powstawanie białek tworzących szlak przekazywania sygnału. Geny te nie występują obecnie u żadnych innych organizmów jednokomórkowych, natomiast występują u zwierząt wielokomórkowych. Gdyby te doniesienia się potwierdziły, wskazywałyby na to, że odkryto wspólnego przodka wielokomórkowców.

Dalsze badania wskazują na siostrzaną pozycję Metazoa[2][3], co oznacza, że wiciowce kołnierzykowe nie są przodkami zwierząt, lecz mają z nimi wspólnych przodków.

W 2007 roku został zsekwencjonowany i przeanalizowany genom Monosiga brevicollis. Zawiera około 9200 bogatych w introny genów i wykazuje wysoki poziom złożoności. Potwierdzono obecność wielu genów charakterystycznych dla wielokomórkowców (w tym kodujących białka adhezyjne oraz domeny białek sygnalizacji międzykomórkowej), wykazano monofiletyzm tej grupy organizmów oraz ich odrębny od wielokomórkowców rozwój ewolucyjny[4].

Tradycyjnie, na podstawie morfologii peryplastu, wyróżniano 3 rodziny: Codonosigidae, Salpingoecidae i Acanthoecidae. Podział taki nie znalazł potwierdzenia w dotychczasowych badaniach molekularnych[3].

Wiciowce kołnierzykowe (Choanoflagellata) – jednokomórkowe, jednojądrowe, wodne, wolno żyjące organizmy eukariotyczne wyposażone w pojedynczą, długą wić otoczoną podobnym do choanocytu gąbek wysokim kołnierzykiem z wypustek cytoplazmatycznych (microvilli), tworzącym rodzaj aparatu filtrującego.

Wiciowce kołnierzykowe są organizmami cudzożywnymi, żyjącymi pojedynczo lub kolonijnie w słonych i słodkich wodach całego świata. Większość z dotychczas opisanych gatunków występuje w strefie pelagialnej lub bentalnej mórz i oceanów, a około 50 gatunków w wodach słodkich. Odżywiają się bakteriami, które są odfiltrowywane z pomocą wspomnianego kołnierzyka. Ich cykl życiowy pozostaje słabo poznany. Tradycyjnie zaliczane były do wiciowców (Flagellata). Są blisko spokrewnione z wielokomórkowcami (Metazoa).

Interesującą cechą budowy komórki tych wiciowców jest obecność dodatkowego ciałka podstawowego leżącego w pobliżu ciałka podstawowego wici. Wiciowce kołnierzykowe rozmnażają się bezpłciowo.

Termin Choanoflagellata został wprowadzony przez Williama Saville-Kenta w 1880. Klasyfikacja biologiczna tej grupy organizmów przez długi czas pozostawała niejasna. Zaliczano je w randze klasy Choanoflagellatea do grzybów (Fungi) lub do typu Choanozoa, w randze typu do protistów (Protista) lub Protozoa. Na podstawie badań genetycznych uznane zostały za klad należący do Opisthokonta. Obecność wici oraz podobieństwo do choanocytów skłaniało wielu badaczy (w tym Buck, 1990, Hausmann i Hülsmann, 1996 oraz Cavalier-Smith, 1987 i 1998) do postawienia hipotezy, że kolonijne Choanoflagellata mogły być przodkami zwierząt wielokomórkowych i grzybów. Sugerowały to również wyniki badania niektórych genów – stwierdzono, że u tych wiciowców występują geny niezbędne do sygnalizacji międzykomórkowej, czyli odpowiedzialne za powstawanie białek tworzących szlak przekazywania sygnału. Geny te nie występują obecnie u żadnych innych organizmów jednokomórkowych, natomiast występują u zwierząt wielokomórkowych. Gdyby te doniesienia się potwierdziły, wskazywałyby na to, że odkryto wspólnego przodka wielokomórkowców.

Dalsze badania wskazują na siostrzaną pozycję Metazoa, co oznacza, że wiciowce kołnierzykowe nie są przodkami zwierząt, lecz mają z nimi wspólnych przodków.

W 2007 roku został zsekwencjonowany i przeanalizowany genom Monosiga brevicollis. Zawiera około 9200 bogatych w introny genów i wykazuje wysoki poziom złożoności. Potwierdzono obecność wielu genów charakterystycznych dla wielokomórkowców (w tym kodujących białka adhezyjne oraz domeny białek sygnalizacji międzykomórkowej), wykazano monofiletyzm tej grupy organizmów oraz ich odrębny od wielokomórkowców rozwój ewolucyjny.

Tradycyjnie, na podstawie morfologii peryplastu, wyróżniano 3 rodziny: Codonosigidae, Salpingoecidae i Acanthoecidae. Podział taki nie znalazł potwierdzenia w dotychczasowych badaniach molekularnych.

Os coanoflagelados (Choanoflagellata, Choanoflagellatea ou Choanomonada) são um táxon de protistas aquáticos (marinhos e de água doce) formados por uma célula arredondada que tem num dos polos um flagelo rodeado por um "colar" de microvilosidades. O flagelo provoca uma corrente de água e o colar filtra as partículas nutritivas, que são depois ingeridas por fagocitose[1].

As 600 espécies de coanoflagelados conhecidas são todas formadas por células muito pequenas que podem viver isoladas, livres ou sésseis, ou na forma de colónias. Possuem, em geral, um revestimento celular de celulose e outros glícidos complexos, embora haja células nuas e outras envolvidas por uma teca rígida. Apenas se conhece a sua reprodução por fissão binária; no entanto, a espécie colonial Proterospongia haeckeli forma células amebóides, que se pensa poderem ter algum papel específico na reprodução.

Estas células são muito semelhantes aos coanócitos das esponjas, o que sugere a existência de um antepassado comum, que poderá ter vivido no final do Pré-Câmbrico, há cerca de um bilhão de anos (mil milhões de anos). Para além disso, estes protozoários podem ser coloniais, agregados por uma matriz gelatinosa; os Acanthoedidae possuem ainda uma teca (um invólucro) rígida, suportada por varetas de sílica, o que permite associá-los às esponjas siliciosas[1].

Análises filogenéticas indicam que este clado pode ser o "irmão" mais próximo dos animais (Metazoa).

Os coanoflagelados são tradicionalmente divididos em duas famílias[1]:

Os coanoflagelados (Choanoflagellata, Choanoflagellatea ou Choanomonada) são um táxon de protistas aquáticos (marinhos e de água doce) formados por uma célula arredondada que tem num dos polos um flagelo rodeado por um "colar" de microvilosidades. O flagelo provoca uma corrente de água e o colar filtra as partículas nutritivas, que são depois ingeridas por fagocitose.

As 600 espécies de coanoflagelados conhecidas são todas formadas por células muito pequenas que podem viver isoladas, livres ou sésseis, ou na forma de colónias. Possuem, em geral, um revestimento celular de celulose e outros glícidos complexos, embora haja células nuas e outras envolvidas por uma teca rígida. Apenas se conhece a sua reprodução por fissão binária; no entanto, a espécie colonial Proterospongia haeckeli forma células amebóides, que se pensa poderem ter algum papel específico na reprodução.

Choanoflagellater är som namnet antyder (flagellater=flagellförsedd organism med choano=krage) encelliga eukaryoter med en flagell och en genomskinlig krage gjord av mikrovilli fäst på cellkroppen[1]. Forskare vet idag inte mycket om deras historia eller levnadssätt.[2] Men morfologiskt sett så kan man anta att vissa arter är närmre släkt med svampar medan vissa är närmre släkt med djur (Animalia). Denna hypotes stöds av bland annat Elisabeth A. Snells forskning om hsp70-genen. Hon sekvenserade genen och studerade stora likheter mellan protister och djur.[3]

Vissa arter av släktet Proterospongia lever i kolonier där de till viss del specialiserar sig till olika egenskaper. Detta visar även på en liknande organisation så som hos cellerna i djur. Runt 150 arter är idag beskrivna.[1]

Kroppen är sfäriskt eller ovalt formad, cirka 3–10 mm i diameter.[2]

De är antingen frisimmande, fastsittande eller lever som kolonier i korta perioder under livscykeln. När de lever i kolonier så förblir de självständiga och specialiserar sig på olika sätt samt kan till viss del kommunicera med varandra. [1]

Deras föda består framförallt av bakterier och detritus (icke-levande organiskt material).[4]

Till utseende så liknar de choanocyter som fungerar som specialiserade celler hos svampar. [1]

Choanoflagellater är frilevande, encelliga och koloniformade eukaryoter som förekommer vanligast i marin miljö såsom bräckt vatten, saltvatten och sötvatten. De finns i hela världen från arktiska till tropiska vatten i både den pelagiska och bentiska zonen. De flesta insamlingarna av choanoflagellater har varit på vattendjup mellan 0–25 meter men man har även upptäckt vissa arter på djup ner till 300 meter i öppna hav [5] och 100 meter under isen i Antarktis[6]. Vissa arter som Diaphanoeca grandis har upptäcks i vatten i Nordamerika, Europa och Australien medan andra arter tros ha en mer lokal utbredning.[7]

Choanoflagellater är de encelliga organismer som är närmast släkt med flercelliga djur. De tillhör gruppen Ophistokonta som kännetecknas av en flagell i bakändan. Därefter har de delats in bland Choanozoa. Choanozoa anses numer som en parafyletisk grupp, innehållande upphovet till animalia. Idag anser man att Opisthokonta bör indelas i tre monofyletiska grupper - Fungi, Nuclearrida och Holozoa. Holozoa är alltså en monofyletisk grupp inom Opisthokonta inom vilken choanoflagellater placeras[8].

Redan under mitten av 1800-talet iakttog biologer morfologiska likheter mellan choanoflagellater och choanocyter hos svampdjur (porifera), det ledde till att man föreslog en nära släktskap mellan choanoflagellater och metazoer. [9]

Moderna fynd har stärkt denna hypotes, bland annat med hjälp av genomkartläggning och idag anses choanoflagellater vara systergrupp till metazoer.[10] Hos arterna Monosiga brevicollis och Salpingoeca rosetta har hela genomet kartlagts och därmed spelat en avgörande roll i jämförande analyser mellan metazoer och chaonoflagellater. [11] [12] En rad gener som hos metazoer kodar för bland annat celladhesion, adhesion till extracellulär matrix och septin har återfunnits hos choanoflagellater. [11] I jämförelse med frilevande choanoflagellater har det hos kolonibildande observerats en uppreglering av särskilda gener som är delade med metazoer. [12] Mitokondriella gensekvenser hos choanoflagellater och olika arter av porifera har jämförts och ytterligare stärkt den nära släktskapen mellan grupperna och placerat choanoflagellaterna som en utgrupp till metazoer. Fynden har även uteslutit möjligheten att choanoflagellaterna har utvecklats ur metazoer. [13]

De är encelliga, pigmentfria[14] organismer där varje cell har en cilium omringad av en ring av mikrovilli som kan dras tillbaka[15]. De flesta choanoflagellater bildar ett sekreterat skelett av silica. Skelettet som kallas lorica (en typ av biologiskt silikon) kan variera mycket i storlek och distribution[16]. Det täcker choanoflagellaten och växer sig vidare mot botten där det fäster och fungerar som ett ankare genom att hålla fast choanoflagellaten.