en

names in breadcrumbs

Common names for Antilocapra americana include pronghorn, pronghorn antelope, and berrendo (Spanish). Antilocapra americana has also been known by the synonyms Antilope americanus, Antilope (Dicranocerus) furcifer, and Antilocapra anteflexa. There are currently five subspecies recognized: American pronghorns (A. a. americana Ord), Oregon pronghorns (A. a. oregona Bailey), Mexican pronghorns(A. a. mexicana Merrian), peninsula pronghorns (A. a. peninsularis Nelson), and Sonoran pronghorns (A. a. sonoriensis Goldman).

The fossil record dates to the Miocene. Antilocapra americana is the only extant species of a group that was once much more diverse, with 13 extinct genera of antilocaprines known from the Pliocene throughout the current range of A. americana.

Doe-fawn recognition seems to be through a combination of visual, vocal, and olfactory cues. Scent glands are widely used in male-male and male-female behavioral interactions. Scent glands are used to mark territories, attract potential mates, identify a mate, alert danger, or deter other males intruding in their territory. Both sexes have rump glands and interdigital glands; males also have a gland below each ear and on the back.

Communication Channels: visual ; acoustic ; chemical

Other Communication Modes: pheromones ; scent marks

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

It is estimated that up to 35 million pronghorns lived in North America before colonization by western Europeans. By 1924 this number had decreased to less than 20,000. Pronghorn populations have increased since that time and are now considered the second most numerous game species in North America.

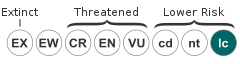

The IUCN Red List lists Antilocapra americana as lower risk/least concern. Populations are stable, widespread, and relatively common throughout most of their range, with an estimated population size of 0.5 to 1 million. The U.S. Endangered Species Act recognizes two populations as endangered: Sonora pronghorns (A. a. sonoriensis) and peninsular pronghorns (A. a. peninsularis). Populations of Sonoran pronghorn in Mexico have been protected since 1967 and have undergone several recovery plans, the most recent in 1998. This population of pronghorn is listed under the Convention of International Trade of Endangered Flora and Fauna (CITES) Appendix I.

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: appendix i

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Pronghorns are grazers that will take advantage of wheat or alfalfa fields during the winter if there is deep snow. This may negatively impact crop yield. However, most pronghorn populations occur in areas with little agricultural development.

Negative Impacts: crop pest

Pronghorns are an important big games species in the western United States. Their use of open habitat means often hunters have success rates of up to 90 percent.

Positive Impacts: food ; body parts are source of valuable material; research and education

Throughout their range pronghorns co-occur with cattle, bison, sheep, and horses. Pronghorns can improve rangeland quality for these other speces by eating noxious weeds or invasive plants. Introduced livestock may overgraze areas they share with pronghorn, thus reducing cover and quantity of food. The reduction of cover may increase young mortality through predation.

Although there are few epizootic diseases that strongly affect pronghorn populations there are 33 species of roundworms, 21 genera of bacteria, 14 viral diseases, 8 species of protozoa, 5 species of tapeworms, 4 species of ticks, one fluke, and a louse fly that are known to infect them. "Bluetongue" disease has resulted in extensive mortality in some cases. It is an insect-borne viral disease (Bluetongue virus, BTV) that is transmitted by midges (Culicoides imicola). Worm infections have also resulted in extensive fawn mortality in some areas. Pronghorns that co-occur with sheep tend to have higher parasite loads than those in areas without sheep. Pronghorns are the definitive host of a nematode worm that also infects sheep and mule deer: Pseudostertagia bullosa (Nematoda: Trichostrongyloidea). They can also be parasitized by meningeal worms (Parelaphostrongylus tenuis) that are common parasites of white-tailed deer.

Mutualist Species:

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Pronghorns are herbivores, eating stems, leaves, grasses and shrubs. Pronghorns have been described as "dainty" feeders, feeding on small amounts of a wide variety of plants. Particularly important in their is browse, especially sagebrush in winter. Pronghorns on grasslands have been observed starving in winter, whereas nearby populations in sagebrush survive well. Forbs with high water content are preferred in the summer diet and grasses are generally eaten only when there is new growth. Cacti are also eaten to some extent, especially in southern populations. Pronghorns use foregut fermentation with rumination to break down cellulose. Their stomach is enlarged and compartmentalized into four chambers, as in other ruminants. Water consumption varies with the water content of the vegetation available locally. When tender leaves are available, with moisture content of 75% or more, pronghorns do not seem to need to drink free-standing water. In dry seasons or areas, pronghorns are typically found within 5 to 6 km of water and may drink up to 3 liters per day.

Pronghorns must compete with introduced cattle (Bos taurus) and sheep (Ovis aries) throughout most of their range. In some areas, pronghorn are excluded from areas used by sheep, because the sheep eliminate much of their preferred vegetation. In other areas pronghorn and sheep seem to be able to coexist well. However, pronghorns can do well on areas overgrazed by cattle because they prefer forbs and browse. It is estimated that 1 cow can eat as much as 38 pronghorns. Fences constructed to enclose cattle and sheep can prevent pronghorn movement across rangeland, resulting in starvation and dehydration. Pronghorns can be considered a valuable part of rangeland management because they eat noxious weeds.

Plant Foods: leaves; roots and tubers; wood, bark, or stems

Primary Diet: herbivore (Folivore )

Antilocapra americana is endemic to North America and distributed throughout the treeless plains, basins, and deserts of western North America, from the southern prairie provinces of Canada, southward into the western United States and to northern Mexico. Distribution of populations within this range is discontinuous. In 1959, a population was introduced to Hawaii. However, by 1983 the population was roughly 12 individuals and headed for extinction.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native )

Pronghorns are primarily found in grassland, sage scrub or chapparal, and desert. The southern portion of their range consists mainly of arid grasslands and open prairies. Throughout the rest of their range they are common in sage scrub and chaparral as well, areas of dense shrubs with tough leaves. Pronghorns are particularly dependent on sage brush for forage in these areas. Pronghorn feed primarily on sage, forbs, and grasses. They have also been known to consume cacti in some areas. There is an overlap in forage preferences with domestic sheep and cattle, so some competition for food occurs. Overgrazing by sheep has been implicated in pronghorn die offs, especially in winter. Pronghorn habitat ranges from sea-level to about 3500 m. Their need for free standing, fresh water varies with the moisture content of the vegetation they consume. They may have to travel a great distance to find a water source. In winter, northern populations depend heavily on sage brush. Pronghorn are commonly found along wind-blown ridges where vegetation has been cleared of snow, although they will dig through snow with their hooves to get to vegetation.

Range elevation: 0 to 3,350 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: desert or dune ; savanna or grassland ; chaparral

Other Habitat Features: suburban ; agricultural

Female pronghorn have been aged at 16 years in the wild, though they seldom live past 9 years. The most common causes of death are predators, hard winters with deep snow, lack of water, and hunting or car collisions. Pronghorns have been recorded living 11 years in captivity.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 16 years.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 11 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 16 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 11.8 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 10.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 10.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: captivity: 12.0 years.

Pronghorns are small ungulates with barrel-shaped bodies. Females stand 860 mm at the shoulder and males 875 mm at the should. Females are approximately 1406 mm in body length and males are approximately 1415 mm. The tail is up to 105 mm long and ears are up to 143 mm long. Their body weight is from 35 to 70 kg, depending on sex and age. Their hair is dense and very coarse and is air-filled, providing excellent insulation. Guard hairs are hollow and underlain by finer, shorter underfur. Guard hairs are erectile for heat regulation. As more air becomes trapped in fur, the more they are insulated from external temperatures. Their dorsal fur is a rufous brown and they have creamy underbellies, rumps, and neck patches. Males have short black manes on the neck, from 70 to 100 mm in length, as well as a neck patch and a black stripe that runs across the forehead from horn to horn. Females lack these black facial patches, but have a small mass of black hair around their nose. Their ears are small and point slightly inward at the tip. Pronghorns have a patch of white, erectile fur on their rumps that is visible at great distances. The mucous membranes and eyelashes are coal black. Southern populations are paler in overall color than northern populations. The horns are erect, with a posterior hook and a short anterior prong. The prong gives rise to the common name “pronghorn”. This pronged pattern is unique to this species. The horn is a keratinized sheath, black in color, and is deciduous. Horn sheaths grow over a bony extension of the frontal bone, which is now called the cancellous bone in ungulates. A new sheath forms under the old, which splits and is dropped just after the rut each year. Both sexes have horns, although the horns of females are generally small or absent, and never exceed ear length. Female horns average about 120 mm and the prongs are not prominent. The horn begins to grow at the age of six months and will be shed by 18 months. The maximum horn height for males will occur within 2 to 3 years of age and will average 250 mm, exceeding the length of the ear.

Pronghorn limbs are specialized for cursoriality, giving them enhanced speed and endurance. They are the fastest known New World mammal, traveling at speeds of 98 km/h when sprinting, and can hold a sustained speed of 59 to 65 km/h. The advantages to having speed and endurance include the ability to forage over large areas, to seek new food sources when familiar sources fail, and the ability to escape predators. Pronghorns have unguligrade foot posture, which lengthens the legs by allowing them to stand on the tips of their digits. The length of the radius bone is as long, or longer, than the femur. The ulna is reduced and partially fused to the radius. The clavicle in ungulates has been lost and the scapula has been reoriented to lie flat against the side of their chest where it is free to rotate roughly 20° to 25° in the same plane in which the leg swings. The ulna and radius have been reduced to eliminate the twisting and rotating of the elbow. The reduction of bone and associated muscles in the distal limbs decreases limb weight, giving them more speed. Pronghorns have modified their joints to act as hinges allowing only motion in the line of travel. This has been done by introducing interlocking spines and grooves in their joints. All these adaptations have made pronghorns excel in cursorial locomotion, but they can no longer jump because they have lost the suspension mechanism that cervids have. This explains their apparent fear of fences.

The dental formula of Antilocapra americana is 0/3-0/1-3/3-3/3, where incisors and canines only occur on the lower jaw. Pronghorns have hypsodont crown height; discernable roots do not occur, allowing the cheek teeth to be ever growing. An approximate age when the molars erupt varies slightly; the first comes in at 2 months and the second and third come in around 15 months of age. Replacement of incisors varies as the first is replaced at 15 months, the second at 27, and the third at 39 months. Canines are replaced between 39 and 41 months. Premolars are all replaced at 27 months of age. The sequence of tooth eruption, replacement, and wear is used to estimate the age of pronghorns. Cementum annuli analysis of the first permanent incisor is used for older age classes.

Maximal rate of oxygen intake in pronghorns determines the peak at which the animal can synthesize ATP by aerobic catabolism. This then determines how intensely the animal can exercise. Pronghorns are an extreme example of evolutionary specialization for high oxygen consumption. When comparing body weight to weight-specific consumption of oxygen, pronghorns have values three times higher than the that expected for their body size. This high oxygen consumption makes pronghorns Earth’s fastest sustained runner. Unlike cheetahs, also one of the fastest animals on Earth, pronghorns produce ATP required to run fast aerobically. They have exceptionally large lungs for their body size and exceptional abilities to maintain high rates of blood circulation.

Range mass: 47 to 70 kg.

Average mass: 50-57 kg.

Range length: 1.75 (high) m.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger; male more colorful; ornamentation

Average basal metabolic rate: 50.973 W.

Fawns or weaker pronghorns are preyed on by coyotes, bobcats, wolves, mountain lions, golden eagles, and other predators within their range. Pronghorns can use their horns to help defend themselves, but they primarily use their speed to escape predators. They are capable of sprints up to 86 km per hour and sustained speeds of 59 to 65 km/hr, making them one of the fastest land mammals. Pronghorns also use their feet in fighting off predators. They have keen eyesight and can spot an object from approximately two miles away. Pronghorns are curious animals and will move towards an intruder until they can detect what it is. If they determine that it is a threat, they will flee. When disturbed, pronghorns erect the white fur on their rumps, which acts to warn others of a disturbance.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

Pronghorns are polygynous. Males defend territories from March through the end of the rut in early October. They defend a small harem of females in their territories during that time. Males with territories that contain a water source and have topographic features that help them corner does, do better than males without those features in their territories. Depending on a female's body condition, she will search among territorial males for potential mates. This behavior may last for two to three weeks. Pronghorns have scent glands that emit pheromones to attract or identify mates. These pheromones are important to interactions between sexes. Scent glands are located on either side of the jaw, between the hooves, on the rump, and above the tail. The glands on the neck are larger in males and are thought to be associated with sexual interaction as they are more active during the rutting season. Before mating, a male will approach a female from behind and shake his head to emit pheromones to attract the female. Males also use scent gland secretions to mark tall grasses on territorial boundaries. Males also mark territories with scrapes where they urinate and defecate, using a stereotypes "sniff, paw, urinate, defecate" sequence that may be repeated. Male interactions can include some or all of the following: 1) staring, 2) vocalization by the territory holder (a decrescendo snort-wheeze), 3) approaching an intruder, which can be accompanied by head thrashing, sneezes, and teeth grinding, 4) interacting with an intruder, and 5) chasing, which can be for only a few meters or up to 5 km. Male use of the snort-wheeze vocalization is often accompanied by erection of the mane, rump patches, and the cheek patches. If an intruder does not run away, then the two males walk in parallel to each other in a slow, deliberate manner with their heads held low. If a fight occurs, the males thrust their horns at each other in an attempt to do injury. Males end up in horn-horn or head-head pushing battles in which they try to knock the other off balance. Fights average only about 2 minutes long, but often result in serious injury.

Mating System: polygynous

Breeding occurs from mid-September to October in northern parts of the pronghorn range and from July to October in southern parts of their range. Females ovulate from 4 to 7 ova at the time of mating. These ova quickly travel to the uterus and form blastocysts, where they absorb nutrition for almost a month before implantation. Blastocysts develop long, thread-like walls that begin to twist together and form knots. One quarter to one third of blastocysts die of malnutrition when this knotting reduces the membrane surface area. As many as 7 embryos may still survive this knotted blastocyst stage. However, as the embryos develop, distal embryos are forced into the oviduct, where they perish from lack of nutrition and are reabsorbed. The gestation period is about 252 days and births are synchronous, with all females giving birth within a few days of each other. Females give birth to one or two fawns in the spring, typically they have a single young in their first year of breeding and twins in subsequent years. Females often labor on their sides, but stand as the front legs of the fawn begin to emerge from the vulva. Females and their young form bands in the summer that roam over the territories of one to several males. Pronghorns have 4 inguinal mammary glands. Young are partially weaned by 3 weeks old, at which point they begin to eat vegetation as well. Most female pronghorns breed in their second year, at about 16 months old, although some females can breed as early as 5 months old. Males can breed in their first year, but rarely do because older, dominant males monopolize breeding opportunities. Males typically begin to breed in their third year.

Breeding interval: Pronghorns breed once yearly.

Breeding season: onghorn range and from July to October in southern parts of their range.

Range number of offspring: 1 to 2.

Average gestation period: 252 days.

Average weaning age: 3 weeks.

Range time to independence: 1 to 1.5 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 5 (low) months.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 16 months.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 1 to 3 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization ; viviparous

Average birth mass: 3000 g.

Average gestation period: 235 days.

Average number of offspring: 2.

Female pronghorns care for their young from 1 to 1.5 years after birth, after which the young will become independent. At the time of birth, the mother will consume the afterbirth to prevent detection by predators. She also consumes any excrement of the young for the first few weeks of their life to prevent detection by predators. For several days after birth young are weak and unable to keep the pace with adults, so mothers and young rest near a source of water until they gain their strength. Females leave their young in a hidden location in vegetation while they forage, but remain within two miles of them. Within minutes after birth, young pronghorns can stand on their own and they nurse within 2 hours. Within days of birth, young pronghorns can outrun a human and begin to travel and forage with their mother and other females and young in summer bands. Siblings are generally on their own until they begin to travel with their mother. Fawns play extensively in the summer herds, developing strength and dexterity. Male pronghorns do not help in raising offspring.

Parental Investment: precocial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Female)

One of nature’s most amazing migrations is that of the pronghorn antelope. Pronghorn have the second longest land mammal migration in North America, a trek of roughly 150 miles coming in second to the caribou which treks over 3000 miles a year (Kostyal, 2011). Given this elite status, it may be somewhat surprising that pronghorn are considered partially migratory; although some individuals migrate long distances seasonally, others only move a few miles a year (White et al., 2007). The Teton herd, known for their extreme migration, travel from their summer foraging grounds in Grand Teton National Park to their wintering grounds in the Green River Basin, south of Pinedale, Wyoming, ins a three to four day, 150-mile trek (Kostyal, 2011). This path is one of only two long-distance migration routes remaining in the Greater Yellowstone region. The other route, located in Idaho, is a much smaller trek of only 80 miles (Cohn, 2010). No matter how short of a journey, both of these herds face many obstacles along the way. The first threat is weather—which is the main reason for these migrations. The weather is a serious threat due to the fact that once snow hits the ground pronghorn antelope lose their biggest advantage: speed. This affects their survival by making them vulnerable to predators, such as wolves (Kostyal, 2011). In addition, deep snow prevents pronghorn from being able to reach their food. If they do not leave the Grand Teton National Park during winter they have high chance of dying due to starvation, predation, hypothermia, or exhaustion, due to difficulties of movement through the deep snow (Cohn, 2010). Another threat to pronghorn is barb wire fences blocking the migration routes. This is a serious issue since pronghorn antelope are not built for jumping. As a result, pronghorn will typically try to go under the fence, causing severe wounds and sometimes deaths due to entanglement (Kostyal, 2011). The most challenging obstacles are highways and interstates. Biologists will even direct traffic to allow them to migrate safely across the roads (Cohn, 2010). Upon arriving in the Green River Basin, the Teton herd spends their winter foraging on the foliage under the snow. As the snow begins to melt in the spring, the migration back to the Grand Teton National Park is a more drawn out journey which happens over roughly two months (Kostyal, 2011). This allows the pronghorn to slowly regain the strength that winter has drained from them. As they become stronger the obstacles become less life-threatening, which allows them to survive the journey back to the Greater Yellowstone area, only to repeat the process the following fall.

Although this is example showcases some of the hazards on long pronghorn migrations, most pronghorn populations do not migrate (Jacques et al., 2009). Over their winter and summer they only move short distances, as small as 13 miles a year (Jacques et al., 2009). The pronghorn that do make extreme migrations such as the Teton herd do so because of the extreme winter weather that occurs in their summer range (Kostyal, 2011). Pronghorn antelope in other regions are not challenged by the severe winter snow that the Teton herd faces, therefore there is no reason for them to move more than a few miles a year for foraging (Jacques et al., 2009).

This taxon is found in the California Central Valley grasslands, which extend approximately 430 miles in central California, paralleling the Sierra Nevada Range to the east and the coastal ranges to the west (averaging 75 miles in longitudinal extent), and stopping abruptly at the Tehachapi Range in the south. Two rivers flow from opposite ends and join around the middle of the valley to form the extensive Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta that flows into San Francisco Bay.

Perennial grasses that were adapted to cool-season growth once dominated the ecoregion. The deep-rooted Purple Needle Grass (Nassella pulchra) was particularly important, although Nodding Needle Grass (Stipa cernua), Wild Ryes (Elymus spp.), Lassen County Bluegrass (Poa limosa), Aristida spp., Crested Hair-grass (Koeleria pyramidata), Deergrass (Muhlenbergia rigens,), and Coast Range Melicgrass (Melica imperfecta) occurred in varying proportions. Most grass growth occurred in the late spring after winter rains and the onset of warmer and sunnier days. Interspersed among the bunchgrasses were a rich array of annual and perennial grasses and forbs, the latter creating extraordinary flowering displays during certain years. Some extensive mass flowerings of the California Poppy (Eschscholzia californica), Lupines (Lupinus spp.), and Exserted Indian Paintbrush (Castilleja exserta) are found in this grassland ecoregion.

Prehistoric grasslands here supported several herbivores including Pronghorn Antelope (Antilocapra americana), elk (including a valley subspecies, the Tule Elk, (Cervus elaphus nannodes), Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus), California ground squirrels, gophers, mice, hare, rabbits, and kangaroo rats. Several rodents are endemics or near-endemics to southern valley habitats including the Fresno Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys nitratoides exilis), Tipton Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys nitratoides nitratoides), San Joaquin Pocket Mouse (Perognathus inornatus), and Giant Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys ingens). Predators originally included grizzly bear, gray wolf, coyote, mountain lion, ringtail, bobcat, and the San Joaquin Valley Kit Fox (Vulpes velox), a near-endemic.

The valley and associated delta once supported enormous populations of wintering waterfowl in extensive freshwater marshes. Riparian woodlands acted as important migratory pathways and breeding areas for many neotropical migratory birds. Three species of bird are largely endemic to the Central Valley, surrounding foothills, and portions of the southern coast ranges, namely, the Yellow-billed Magpie (Pica nuttalli), the Tri-colored Blackbird (Agelaius tricolor EN), and Nuttall’s Woodpecker (Picoides nuttallii).

The valley contains a number of reptile species including several endemic or near-endemic species or subspecies such as the San Joaquin Coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum ruddocki), the Blunt-nosed Leopard Lizard (Gambelia sila EN), Gilbert’s Skink (Plestiodon gilberti) and the Sierra Garter Snake (Thamnophis couchii). Lizards present in the ecoregion include: Coast Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma coronatum NT); Western Fence Lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis); Southern Alligator Lizard (Elgaria multicarinata); and the Northern Alligator Lizard (Elgaria coerulea).

There are only a few amphibian species present in the California Central Valley grasslands ecoregion. Special status anuran taxa found here are: Foothill Yellow-legged Frog (Rana boylii NT); Pacific Chorus Frog (Pseudacris regilla); and Western Spadefoot Toad (Pelobates cultripes). The Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) occurs within this ecoregion.

Although many endemic plant species are recognized, especially those associated with vernal pools, e.g. Prickly Spiralgrass (Tuctoria mucronata). A number of invertebrates are known to be restricted to California Central Valley habitats. These include the Delta Green Ground Beetle (Elaphrus viridis CR) known only from a single vernal pool site, and the Valley Elderberry Longhorn Beetle (Desmocerus californicus dimorphus) found only in riparian woodlands of three California counties.

Vernal pool communities occur throughout the Central Valley in seasonally flooded depressions. Several types are recognized including valley pools in basin areas which are typically alkaline or saline, terrace pools on ancient flood terraces of higher ground, and pools on volcanic soils. Vernal pool vegetation is ancient and unique with many habitat and local endemic species. During wet springs, the rims of the pools are encircled by flowers that change in composition as the water recedes. Several aquatic invertebrates are restricted to these unique habitats including a species of fairy shrimp and tadpole shrimp.

This taxon is found in the Chihuahuan Desert, which is one of the most biologically diverse arid regions on Earth. This ecoregion extends from within the United States south into Mexico. This desert is sheltered from the influence of other arid regions such as the Sonoran Desert by the large mountain ranges of the Sierra Madres. This isolation has allowed the evolution of many endemic species; most notable is the high number of endemic plants; in fact, there are a total of 653 vertebrate taxa recorded in the Chihuahuan Desert.Moreover, this ecoregion also sustains some of the last extant populations of Mexican Prairie Dog, wild American Bison and Pronghorn Antelope.

The dominant plant species throughout the Chihuahuan Desert is Creosote Bush (Larrea tridentata). Depending on diverse factors such as type of soil, altitude, and degree of slope, L. tridentata can occur in association with other species. More generally, an association between L. tridentata, American Tarbush (Flourensia cernua) and Viscid Acacia (Acacia neovernicosa) dominates the northernmost portion of the Chihuahuan Desert. The meridional portion is abundant in Yucca and Opuntia, and the southernmost portion is inhabited by Mexican Fire-barrel Cactus (Ferocactus pilosus) and Mojave Mound Cactus (Echinocereus polyacanthus). Herbaceous elements such as Gypsum Grama (Chondrosum ramosa), Blue Grama (Bouteloua gracilis) and Hairy Grama (Chondrosum hirsuta), among others, become dominant near the Sierra Madre Occidental. In western Coahuila State, Lecheguilla Agave (Agave lechuguilla), Honey Mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa), Purple Prickly-pear (Opuntia macrocentra) and Rainbow Cactus (Echinocereus pectinatus) are the dominant vascular plants.

Because of its recent origin, few warm-blooded vertebrates are restricted to the Chihuahuan Desert scrub. However, the Chihuahuan Desert supports a large number of wide-ranging mammals, such as the Pronghorn Antelope (Antilocapra americana), Robust Cottontail (Sylvilagus robustus EN); Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus), Grey Fox (Unocyon cineroargentinus), Jaguar (Panthera onca), Collared Peccary or Javelina (Pecari tajacu), Desert Cottontail (Sylvilagus auduboni), Black-tailed Jackrabbit (Lepus californicus), Kangaroo Rats (Dipodomys sp.), pocket mice (Perognathus spp.), Woodrats (Neotoma spp.) and Deer Mice (Peromyscus spp). With only 24 individuals recorded in the state of Chihuahua Antilocapra americana is one of the most highly endangered taxa that inhabits this desert. The ecoregion also contains a small wild population of the highly endangered American Bison (Bison bison) and scattered populations of the highly endangered Mexican Prairie Dog (Cynomys mexicanus), as well as the Black-tailed Prairie Dog (Cynomys ludovicianus).

The Chihuahuan Desert herpetofauna typifies this ecoregion.Several lizard species are centered in the Chihuahuan Desert, and include the Texas Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum); Texas Banded Gecko (Coleonyx brevis), often found under rocks in limestone foothills; Reticulate Gecko (C. reticulatus); Greater Earless Lizard (Cophosaurus texanus); several species of spiny lizards (Scelopoprus spp.); and the Western Marbled Whiptail (Cnemidophorus tigris marmoratus). Two other whiptails, the New Mexico Whiptail (C. neomexicanus) and the Common Checkered Whiptail (C. tesselatus) occur as all-female parthenogenic clone populations in select disturbed habitats.

Representative snakes include the Trans-Pecos Rat Snake (Bogertophis subocularis), Texas Blackhead Snake (Tantilla atriceps), and Sr (Masticophis taeniatus) and Neotropical Whipsnake (M. flagellum lineatus). Endemic turtles include the Bolsón Tortoise (Gopherus flavomarginatus), Coahuilan Box Turtle (Terrapene coahuila) and several species of softshell turtles. Some reptiles and amphibians restricted to the Madrean sky island habitats include the Ridgenose Rattlesnake (Crotalus willardi), Twin-spotted Rattlesnake (C. pricei), Northern Cat-eyed Snake (Leptodeira septentrionalis), Yarrow’s Spiny Lizard (Sceloporus jarrovii), and Canyon Spotted Whiptail (Cnemidophorus burti).

There are thirty anuran species occurring in the Chihuahuan Desert: Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana chircahuaensis); Red Spotted Toad (Anaxyrus punctatus); American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus); Canyon Treefrog (Hyla arenicolor); Northern Cricket Frog (Acris crepitans); Rio Grande Chirping Frog (Eleutherodactylus cystignathoides); Cliff Chirping Frog (Eleutherodactylus marnockii); Spotted Chirping Frog (Eleutherodactylus guttilatus); Tarahumara Barking Frog (Craugastor tarahumaraensis); Mexican Treefrog (Smilisca baudinii); Madrean Treefrog (Hyla eximia); Montezuma Leopard Frog (Lithobates montezumae); Brown's Leopard Frog (Lithobates brownorum); Yavapai Leopard Frog (Lithobates yavapaiensis); Western Barking Frog (Craugastor augusti); Mexican Cascade Frog (Lithobates pustulosus); Lowland Burrowing Frog (Smilisca fodiens); New Mexico Spadefoot (Spea multiplicata); Plains Spadefoot (Spea bombifrons); Pine Toad (Incilius occidentalis); Woodhouse's Toad (Anaxyrus woodhousii); Couch's Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus couchii); Plateau Toad (Anaxyrus compactilis); Texas Toad (Anaxyrus speciosus); Dwarf Toad (Incilius canaliferus); Great Plains Narrowmouth Toad (Gastrophryne olivacea); Great Plains Toad (Anaxyrus cognatus); Eastern Green Toad (Anaxyrus debilis); Gulf Coast Toad (Incilius valliceps); and Longfoot Chirping Toad (Eleutherodactylus longipes VU). The sole salamander occurring in the Chihuahuan Desert is the Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum).

Common bird species include the Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx californianus), Burrowing Owl (Athene cunicularia), Merlin (Falco columbarius), Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), and the rare Zone-tailed Hawk (Buteo albonotatus). Geococcyx californianus), Curve-billed Thrasher (Toxostoma curvirostra), Scaled Quail (Callipepla squamata), Scott’s Oriole (Icterus parisorum), Black-throated Sparrow (Amphispiza bilineata), Phainopepla (Phainopepla nitens), Worthen’s Sparrow (Spizella wortheni), and Cactus Wren (Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus). In addition, numerous raptors inhabit the Chihuahuan Desert and include the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) and the Elf Owl (Micrathene whitneyi).

El berrendo o antílope americanu (Antilocapra americana) ye una especie de mamíferu artiodáctilu de la familia Antilocapridae.[2] Tratar del únicu representante actual de la so familia, anque hasta principios del Pleistocenu cuntaba con numberoses especies. Col pasu del tiempu, toos s'escastaron por diversu causes, dexando al berrendo actual como única muerte de la so presencia.

Magar que son llamaos antílopes americanos nun son verdaderos antílopes.[3] Presenta un marcáu dimorfismu sexual, siendo los machos mayores, con un pesu de 45-60 kg, ente que les femes pesen ente 35 y 45 kg. Difier del restu de rumiantes de cuernos buecos por tener estoxos córneos caducos. Dambos sexos tienen cuernos curvos y empobinaos escontra tres que camuden cada añu, como los venaos, pero nunca s'esprenden de la base ósea qu'hai so la superficie córnea. Estos cuernos son más grandes y tán ramificaos nos machos (125 a 450 mm), ente que les femes tener curtios y ensin ramificaciones (25 a 150 mm).Tanto les femes como los machos tienen una corona de pelo na base de los cuernos y una clina de color negru.

El so llargor corporal ye de 1,30 a 1,50 m, una alzada a la cruz de 70 a 80 cm y la so cola tien un llargor de 10 cm ente qu'el so oreyes tener de 15 cm.

La forma del cuerpu recuerda a los antílopes, yá que al igual qu'ellos, tienen el llombu a mayor altor que los costazos. Les sos estremidaes son delgaes y llargues y nun tienen díxitos llaterales En cuanto a la pelame, ye leonado o berrendo nel llombu, d'onde provien el so nome en castellán, anque pel iviernu escurezse llixeramente. Esclariar nes partes inferiores del cuerpu hasta volvese blancu en cara, gargüelu, banduyu, pates y gluteos. Un elementu característicu d'esta especie, ye la presencia d'un gran llurdiu blancu alredor de la rexón caudal, ta presente en machos, femes y críes, la pelame nesta zona se eriza cuando l'animal presiente dalgún peligru, sirviendo d'alvertencia a otros miembros del grupu. Na parte del pescuezu sobresalen dos bandes blanques alcontraes una al altor del gargüelu y otra debaxo d'ella. Esisten bandes de pelo escuru en ñariz, frente, carriellos, parte posterior del pescuezu y envés de la cola. Les pates tienen cuatro dedos, anque caminen sobre dos.

El berrendo ye propiu de Norteamérica, atopándose dende'l sur de Canadá, al traviés del oeste de los Estaos Xuníos, hasta'l norte de Méxicu (Baxa California, Sonora, Chihuahua y Hidalgo).[1]

El hábitat característicu d'estos animales son los espacios abiertos, como llanures herbales y semidesiertos.

Alimentar mientres gran parte del día de yerbes, parrotales, mofos y n'ocasiones inclusive cactus. Los berrendos mover en grandes grupos, dacuando en menaes de cientos d'animales, especialmente en branu. Los integrantes d'estes menaes son siempres femes coles sos críes y machos nuevos. Los machos adultos o vieyos suelen ser solitarios o viven en pequeños grupos, anque dacuando pueden formar tamién fataos formaos namái por individuos masculinos. En seronda, los machos n'edá reproductora compiten ente sigo lluchando cabeza contra cabeza col fin de ganase'l derechu a reproducise. Al contrariu qu'en munchos otros ungulaos, los machos nun abandonen les menaes de femes y nueves tres la dómina de celu, sinón que se xunen a elles mientres tol iviernu siguiente.

Tres 230 díes de xestación, les femes paren una cría (si ye'l so primer partu) o dos nel mes de xunu. Estos pequeños son de color gris y pesen de 2 a 4 kg. Darréu tres el partu, les femes dixebren a les sos críes y esconder ente la maleza, anque se caltienen vixilantes nes zones próximes y alleguen regularmente pa da-yos de mamar.

Anguaño nun cunten con auténticos depredadores. Son los mamíferos más rápidos de Norteamérica,[4] pudiendo correr a 65 km/h mientres dellos kilómetros, saltando de 3 hasta cuasi 6 metros.[3] La so velocidá máxima rexistrada ye de 98 km/h.[ensin referencies]

Por cuenta de ello, ye raru que muerran preses d'otros animales. Los llobos, coyotes, llobos cervales, pumes y águiles reales pueden matar críes de pocos díes, pero inclusive esto nun ye daqué común, pos los pequeños berrendos pueden pasar hores agazupaos ente la vexetación y ensin realizar movimientu dalgunu que pueda delatalos. A les poques selmanes de nacer dexen d'escondese y siguen a la so madre, siendo yá más rápidos que los sos potenciales cazadores hasta entós.

La posible causa de la velocidá del antílope americanu ye qu'hasta fai apenes 20 milenios sí tenía un depredador del qu'esmolecese de verdá. Nes praderíes americanes habitaben felíns similares al guepardu d'Asia y África, pertenecientes al xéneru estinguíu Miracinonyx, que probablemente algamaben velocidaes similares a ésti (105 km/h en tramos curtios). La velocidá y la resistencia a la carrera desenvolver col fin de da-yos safazu, y cuando los guepardos americanos escastar a finales de la postrera glaciación, los berrendos a cencielles siguieron siendo igual de rápidos qu'hasta entós.

Por cuenta de esta ausencia de depredadores, los antílopes americanos multiplicar ensin problemes mientres el Holocenu, y a la llegada de los primeros europeos formaben menaes de millones d'exemplares nes llanures de Canadá, Estaos Xuníos y Méxicu. Esto camudó cola llamada “conquista del Oeste”. Al igual que los bisontes, los berrendos fueron oxetu d'una brutal matanza a manes de los colonos mientres tol sieglu XIX, morriendo miles cada añu. En 1908, quedaben menos de 20.000 exemplares en tol mundu. Primero que la especie menguara más se dictaron lleis pa protexela a ella y el so hábitat, polo que la población aumentó anguaño hasta cuasi los 3 millones d'animales, siendo especialmente abondosos nes zones protexíes de Wyoming y Colorado. En delles zones la caza volvió ser dexada col fin de controlar l'escesu de población.

Reconócense les siguientes subespecies:[2][5]

AA.VV (2009)“Berrendo (Antilocapra americana)” estrayíu'l 2 d'abril de 2011 de: http://www.conanp.gob.mx/pdf_especies/pace_berrendo.pdf

El berrendo o antílope americanu (Antilocapra americana) ye una especie de mamíferu artiodáctilu de la familia Antilocapridae. Tratar del únicu representante actual de la so familia, anque hasta principios del Pleistocenu cuntaba con numberoses especies. Col pasu del tiempu, toos s'escastaron por diversu causes, dexando al berrendo actual como única muerte de la so presencia.

Amerika haçabuynuzu (lat. Antilocapra americana) - haçabuynuz cinsinə aid heyvan növü.

Amerika haçabuynuzu (lat. Antilocapra americana) - haçabuynuz cinsinə aid heyvan növü.

Antilopenn Amerika (Antilocapra americana) a zo ur bronneg daskirier hag a vev e Norzhamerika.

Ar spesad nemetañ eo er c'herentiad Antilocapridae.

Eil loen douarel vuanañ ar bed eo (betek 88,5 km/h) hag ar c'hentañ war hedoù hir (betek 56 km/h war 6 km).

L'antílop americà (Antilocapra americana) és una espècie d'ungulat nadiu de Nord-amèrica. Es tracta de l'únic representant actual dels antilocàprids, una família d'artiodàctils que fins a principis del Plistocè comptava amb nombroses espècies. Tanmateix, amb el pas del temps totes les altres espècies s'extingiren per diverses causes, deixant l'antílop americà com a únic vestigi de la seva existència.

El nom vulgar de l'antílop americà pot causar confusió, car en realitat no es tracta d'un antílop autèntic (a diferència dels antílops autèntics, l'antílop americà té banyes ramificades que es muden cada any).

L'antílop americà (Antilocapra americana) és una espècie d'ungulat nadiu de Nord-amèrica. Es tracta de l'únic representant actual dels antilocàprids, una família d'artiodàctils que fins a principis del Plistocè comptava amb nombroses espècies. Tanmateix, amb el pas del temps totes les altres espècies s'extingiren per diverses causes, deixant l'antílop americà com a únic vestigi de la seva existència.

El nom vulgar de l'antílop americà pot causar confusió, car en realitat no es tracta d'un antílop autèntic (a diferència dels antílops autèntics, l'antílop americà té banyes ramificades que es muden cada any).

Vidloroh americký (Antilocapra americana) Je to jediný zástupce čeledi vidlorohovitých, který představuje přechod mezi jelenovitými a turovitými. Je jedním z nejrychlejších savců planety. Jsou známy čtyři poddruhy: vidloroh americký (Antilocapra americana americana), vidloroh arizonský (Antilocapra americana mexicana), vidloroh kalifornský (Antilocapra americana peninsularis) a vidloroh sonorský (Antilocapra americana sonoriensis).

Severoameričtí indiáni vidloroha často lovili pro maso, a především pro jemnou kůži, která byla ceněna ještě víc než jelenice. Zhotovovaly se z ní ženské oděvy, mokasíny, váčky a další předměty. Indiáni vidloroha pokládali za druh jelena, svědčí o tom i některé z následujících názvů, např. v kríjštině doslova "malý karibu", lakotštině "světlý jelen" nebo nahuatlu "posvátný jelen".[2]

Vidloroh se vyvíjel v Severní Americe, kde je jedním z nejstarších savců. Z toho důvodu nemá na ostatních světadílech žádné příbuzné.

Tělo je porostlé světle hnědou srstí, břicho a spodní části hlavy a krku jsou bílé. Je-li horko, chlupy se zježí, v zimě zase přilnou k pokožce, aby chránily zvíře před chladem. Ocas je obklopen dlouhými bílými chlupy,v případě ohrožení naježí, čímž varují ostatní vidlorohy. Samci i samice mají vidlicovitě rozvětvené rohy, jejichž konce jsou ohnuté dozadu. Na rozdíl od jiných rohatých sudokopytníků je každoročně shazují, asi do čtyř měsíců jim narůstají nové. Ocas měří okolo 10 cm. Samci se od samic liší černým zakončením čenichu a delšími rohy (až 50 cm).

Vidlorozi mají výborný zrak. Patří mezi nejrychlejší suchozemská zvířata. Jejich maximální rychlost je nicméně předmětem sporů, údaje se pohybují od 70 do 100 km/h.[12][13] Vysokou rychlost (přes 50 km/h) jsou schopni si udržet po mnoho kilometrů. Umožňují jim to velké plíce, objemné srdce a široká průdušnice. Průměrná délka života je deset let.

S vidlorohy se nejčastěji můžeme setkat na Velkých pláních, areál jejich výskytu však zasahuje i do Skalnatých hor a polopouštních oblastí na jihozápadě USA a na severu Mexika.

Vidlorozi jsou přežvýkavci. Jejich jídelníček tvoří traviny a větve keřů, v případě nedostatku i kaktusy. Velmi dobře snášejí žízeň.

Říje probíhá od září do poloviny října, kdy kolem sebe samci vytvoří skupinu tří až čtyř samic. V květnu až červnu se rodí mláďata, většinou dvojčata, která váží přibližně 2 kg. Matka je rozmístí do úkrytů vzdálených od sebe asi 100 m, kam je chodí kojit. Jestliže je jedno mládě napadeno predátorem, druhé tak má šanci uniknout. Samečci mají našedlou srst, jež po třech měsících zhnědne. Do jednoho roku se objevují rohy.

Vidlorozi se sdružují do stád, která v minulosti čítala i několik set jedinců. V době říje se rozptýlí a znovu se shromažďují na začátku zimy. Jsou velmi plaší, když však spatří něco neobvyklého, zvědavost je přinutí prohlédnout si to zblízka.

Vidlorohy potkal podobný osud jako bizony. Když se na americký Západ dostali první běloši, pohybovalo se zde 40–50 milionů těchto zvířat. Za jedno století se početní stavy vidlorohů snížily na 19 000 kusů. Byla přijata přísná opatření na jejich ochranu, díky čemuž se jejich populace začala opět zvětšovat. V současnosti žije v Severní Americe přibližně 400 000 vidlorohů.

Vidloroh americký (Antilocapra americana) Je to jediný zástupce čeledi vidlorohovitých, který představuje přechod mezi jelenovitými a turovitými. Je jedním z nejrychlejších savců planety. Jsou známy čtyři poddruhy: vidloroh americký (Antilocapra americana americana), vidloroh arizonský (Antilocapra americana mexicana), vidloroh kalifornský (Antilocapra americana peninsularis) a vidloroh sonorský (Antilocapra americana sonoriensis).

Gaffelbukken (Antilocapra americana) er den eneste art i slægten Antilocapra, som tillige er den eneste slægt i familien Antilocapridae. Dyret når en længde på 1-1,5 m med en hale på 7,5-18 cm og en vægt på 36-70 kg. Den lever i det vestlige og centrale Nordamerika. Den lever af planter. Om vinteren lever dyret i flokke på over 1000 individer, der dog splittes op om sommeren.

Der Gabelbock (Antilocapra americana), auch als Gabelhornantilope, Gabelantilope, Gabelhorntier, Gabelhornträger oder Pronghorn bekannt, ist ein nordamerikanischer Wiederkäuer der Prärie. Obwohl seine Gestalt an die Antilopen Afrikas und Asiens erinnert, gehört er nicht zu deren Familie der Hornträger. Er bildet die heute monotypische Familie der Gabelhornträger (Antilocapridae) als ihr einziger rezenter Vertreter.

Der Gabelbock ist in etwa so groß wie ein Damhirsch. Er hat eine Kopfrumpflänge von bis zu 150 Zentimetern (der Schwanz ist 8 bis 15 cm lang), eine Körperhöhe von 90 Zentimetern und ein Gewicht von 50 bis 70 Kilogramm. Die Männchen sind etwas größer als die Weibchen (Sexualdimorphismus). Das Fell ist oberseits gelb- bis rotbraun und unterseits bis zu den Flanken weiß gefärbt; weiße Bänder finden sich zudem auf der Vorderseite des Halses und um das Maul herum. Die Männchen haben außerdem eine schwarze Zeichnung im Gesicht und am Hals. Ein Gabelbock kann seine Körperhaare aufrichten. Durch das Aufstellen der weißen Rumpfhaare gibt er ein weithin sichtbares Signal, das in einer Herde als Warnung wahrgenommen wird.

Unterscheidbar sind die Geschlechter auch durch die Hörner. Beim Männchen können sie bis zu 25 cm lang werden (meist sind sie doppelt so lang wie die Ohren) und gabeln sich in ein kurzes nach vorne gerichtetes und ein langes nach oben gerichtetes und etwas zurückgebogenes Ende – von dieser Eigenschaft leitet sich ihr deutscher Name ab. Weibchen haben oft gar keine Hörner; falls doch, dann sind diese niemals länger als die Ohren.

Unter den Sinnesorganen des Gabelbocks kommt dem Auge die größte Bedeutung zu. Durch die Lage der Augen an den Kopfseiten hat ein Gabelbock die Möglichkeit, ein Blickfeld von nahezu 360° zu beobachten. Gehör- und Geruchssinn sind von etwas geringerer Bedeutung, beide sind aber dennoch gut entwickelt. Die Ohren können aufgestellt und in verschiedene Richtungen gewendet werden. Die Nase spielt vor allem beim Erkennen von Reviergrenzen eine Rolle.

Anders als bei anderen Paarhufern fehlen die Afterklauen vollständig, die Gliedmaßen tragen also nur die dritte und die vierte Zehe.

Gabelböcke zeichnen sich durch eine außergewöhnliche Sprungkraft aus. So können sie mit einem einzigen Sprung bis zu sechs Meter vorwärts schnellen.

Der Gabelbock besitzt ein reduziertes Gebiss: im Unterkiefer sind je Kieferhälfte 3 Schneidezähne, 1 Eckzahn, 3 Prämolaren und 3 Molaren ausgebildet, im Oberkiefer fehlen die Schneide- und Eckzähne. Die Zahnformel lautet somit 0.0.3.3 3.1.3.3 {displaystyle {frac {0.0.3.3}{3.1.3.3}}}

Eine Besonderheit stellen die Hörner dar, die direkt oberhalb des Augenfensters ansetzen. Wie die der Hornträger bestehen sie aus einer knöchernen Grundlage (Schaft), die mit Keratin überzogen ist (Hornscheide). Dabei gabelt sich der Hornschaft beim heutigen Gabelbock selber nicht, nur der Keratinüberzug bildet die beiden Hornspitzen aus. Jedes Jahr werden die Hornscheiden nach der Brunft etwa ab Oktober gewechselt. Nur die Knochenzapfen bleiben zeitlebens bestehen, während die Hornscheide sich ablöst und zu Boden fällt. Darunter hat sich zu diesem Zeitpunkt bereits neue Hornmasse gebildet, die noch mit einem pelzigen Überzug bedeckt ist. Das jährliche Wachstum des Keratinüberzuges ist nach rund zehn Monaten abgeschlossen. In dieser Hinsicht ähnelt der Gabelbock den Hirschen, die ihr Geweih jährlich wechseln, weicht aber markant von den Hornträgern ab, bei denen es nicht zu einem Austausch der Hornscheide kommt. Fossile Vertreter der Gabelhornträger besaßen zum Teil sehr komplexe Hörner mit mehreren oder vielfach gegabelten beziehungsweise in sich gedrehten Schäften. Hier ist unklar, ob es ebenfalls zu einem jährlichen Abrieb der Hornscheide kam. Einige Experten sehen darin ein besonderes Merkmal des heute lebenden Gabelbocks. Die frühesten Gabelhornträger besaßen noch mit Haut überzogene Hörner, was anhand von Blutkanälchen an den Hornschäften nachgewiesen wurde.[4][3]

Der Gabelbock entwickelte sich in den Grasländern Nordamerikas und war einst weit über die Prärie und auch in den Wüsten und Halbwüsten der südwestlichen USA sowie des nordwestlichen Mexiko verbreitet. Er bevorzugt Regionen mit weitem Sichtfeld und einer mosaikartigen Vegetation aus offenen Steppen- und Staudenlandschaften. Ursprünglich über weite Bereiche der Großen Ebenen bis hin zum Saskatchewan River im Norden verbreitet, ist er seit der Besiedlung Nordamerikas durch die Europäer in höhere Gebirgslagen des westlichen Kontinentalteiles zurückgedrängt worden. In den Rocky Mountains kommt er bis in Höhen von 3350 m vor. Generell meidet der Gabelbock geschlossenere Landschaften (siehe auch: Bedrohung und Schutz).[1][2]

Gabelböcke können zu allen Tages- und Nachtzeiten aktiv sein, sind dies jedoch überwiegend während der Dämmerung. Wo die Umstände es erforderlich machen, führen sie jahreszeitliche Wanderungen durch, die über Strecken von bis zu 260 Kilometern[5] führen können. Dies ist beispielsweise in Wüsten notwendig, um Wasserläufe zu suchen, oder in felsigen Gegenden, die im Winter kein ausreichendes Nahrungsangebot haben. Die weitesten untersuchten Wanderungen führen aus dem Grand-Teton-Nationalpark über die Gros Ventre Range zum Oberlauf des Green Rivers in Wyoming.[6]

Im Sommer werden ältere Männchen zu Einzelgängern und versuchen, durch Kämpfe ein Territorium zu erstreiten. In diesem sammeln sie einen Harem um sich. Ein Territorium kann vier Quadratkilometer umfassen und wird durch Urin markiert und somit abgesteckt. Das Männchen ist fortan damit beschäftigt, andere Männchen am Betreten und Weibchen am Verlassen des Territoriums zu hindern. Bei einem Aufeinandertreffen zweier Männchen reichen meistens Drohgebärden mit lauten Schreien und Scheinattacken aus, um über Sieger und Verlierer zu entscheiden. Kommt es doch einmal zum Kampf, können die scharfkantigen Hörner ernsthafte Verletzungen und sogar den Tod verursachen.

Im Herbst und im Winter tun sich all die kleinen Verbände mit einzelgängerischen Männchen zu großen Herden zusammen, die in historischen Zeiten mehrere zehntausend Tiere umfassen konnten, heute jedoch maximal aus wenig mehr als 1000 Tieren bestehen.

Jüngere Männchen, die noch nicht kämpfen können, finden sich zu kleinen Verbänden zusammen; alte Männchen, die zu schwach zum Kämpfen geworden sind, bleiben einzelgängerisch und versuchen, den Revieren der Artgenossen auszuweichen. Die Weibchen leben in Gruppen von etwa 20 Tieren. Nach einer Tragzeit von achteinhalb Monaten sondert sich das Weibchen von der Herde ab und bringt ein bis zwei, sehr selten drei Junge mit einem Geburtsgewicht von etwa drei Kilogramm zur Welt. Diese haben zunächst ein graues Fell, das nach drei Monaten die typischen Farben der Alttiere annimmt. Die ersten drei Tage werden sie in einem Versteck gehalten, und etwa nach einer Woche können junge Gabelböcke selbst rennen. Obwohl sie schon nach drei Wochen Gras zu sich nehmen, werden sie noch fünf bis sechs Monate lang gesäugt. Die Geschlechtsreife erreichen die Weibchen mit 15 bis 16, die Männchen mit etwa 24 Monaten.

Gabelböcke haben eine geringe Lebenserwartung und werden selbst unter günstigen Umständen selten älter als zehn Jahre.

Der Gabelbock ist stark wählerisch in seinem Nahrungsverhalten. Generell ernährt er sich von verschiedenen Pflanzen, vor allem von Kräutern, Blättern, Sprossen und Gräsern. Häufig verbringt ein Tier nur relativ kurze Zeit, etwa eine halbe Minute, an einer Nahrungsressource. Vor allem im Frühjahr und zu Beginn des Sommers bevorzugt der Gabelbock Gras, während er im Herbst und Winter Blätter an Stauden frisst. Bedeutend sind hierbei vor allem Artemisia-Gewächse. In Trockenlandschaften bilden zudem Kakteen einen Teil der Ernährungsgrundlage.[1][2]

Im Laufen können Gabelböcke Geschwindigkeiten von 60 bis 70 km/h erreichen; anhand von gemessenen Schrittlängen wurde sogar eine Geschwindigkeit von 86,5 km/h angenommen.[7] Derart hohe Geschwindigkeiten können über eine Strecke von bis zu fünf Kilometern durchgehalten werden. Eine Distanz von 11 Kilometern können sie in 10 Minuten bei einer Durchschnittsgeschwindigkeit von 65 km/h überwinden. Die Tiere sind also eher Langstreckenläufer als Sprinter. Die körperliche Anpassung an solche Geschwindigkeiten besteht nicht nur in dem schlanken Körperbau und den kräftigen Beinen, sondern auch in einer Vergrößerung von Lungen und Herz – das Herz eines Gabelbocks ist etwa doppelt so groß wie das eines Hausschafs. Weitere Anpassungen bestehen beispielsweise in einer erhöhten Anzahl der Mitochondrien pro Muskelvolumen. Es sind solche Verstärkungen der allgemeinen Säugetierstrukturen – und nicht die Entwicklung neuer Strukturen –, die es dem Gabelbock ermöglichen, einen höheren Sauerstoffanteil aus der Atemluft aufzunehmen und zu verwerten, als es für ein Säugetier seiner Größe zu erwarten ist.[8]

Oft stößt man auf die Aussage, Gabelböcke seien nach dem Gepard die schnellsten Säugetiere der Welt.[8] Hier ist aber die Frage, ob die Höchst- oder die Durchschnittsgeschwindigkeit gemeint ist. Über sehr kurze Distanzen können manche afrikanisch-asiatische Antilopen, wie zum Beispiel die Hirschziegenantilope, die gleiche Geschwindigkeit erreichen. Allerdings sind Gabelböcke die schnellsten Säugetiere des amerikanischen Doppelkontinents und, gemessen über eine Strecke von fünf Kilometern, wahrscheinlich sogar die schnellsten Säugetiere überhaupt.

Die natürlichen Feinde des Gabelbocks sind vor allem der Wolf, der Kojote und der Puma.[7] Diese reißen ob der Schnelligkeit ihrer Beutetiere jedoch meistens nur junge, alte oder kranke Individuen. Durch gezielte Tritte mit den Hinterhufen versuchen Gabelböcke, sich gegen die Angreifer zur Wehr zu setzen, was vor allem bei Kojoten oft Erfolg hat. Als Hauptwaffe gegen Fressfeinde gilt aber ihre Geschwindigkeit. Neben diesen natürlichen Feinden stellt jedoch auch der Mensch eine große Bedrohung für den Gabelbock dar.

Zu den ursprünglichen natürlichen Feinden gehörten unter anderem der Gepard Miracinonyx trumani, der Löwe Panthera atrox und möglicherweise auch der Kurznasenbär.[7] Da die maximale Höchstgeschwindigkeit von 86 km/h weit höher ist als nötig, um den heutigen Jägern zu entkommen, wurde teilweise angenommen, dass der Gabelbock aufgrund von Nachstellungen durch Miracinonyx seine guten Laufeigenschaften entwickelt habe.[7] Dieses mutmaßliche Beispiel einer Koevolution in der Räuber-Beute-Beziehung (auch Red-Queen-Hypothese) lässt sich nach Ansicht zahlreicher Wissenschaftler jedoch nicht belegen: Während schon die frühesten Vertreter der Gabelhornträger vom beginnenden Miozän an vor rund 20 Millionen Jahren aus anatomischen Gründen als extrem schnelle Läufer anzusehen sind, stammt der älteste Nachweis der Katze in Nordamerika erst aus dem ausgehenden Pliozän.[9]

Tayassuidae (Nabelschweine)

Suidae (Echte Schweine)

Camelidae (Kamele)

Hippopotamidae (Flusspferde)

Cetacea (Wale)

Tragulidae (Hirschferkel)

Antilocapridae

Giraffidae (Giraffenartige)

Cervidae (Hirsche)

Moschidae (Moschustiere)

Bovidae (Hornträger)

Der Gabelbock wird als eigenständige Art und monotypische Gattung Antilocapra den Wiederkäuern (Ruminantia) innerhalb der Paarhufer (Artiodactyla) zugeordnet. Dort bildet er zudem die Familie der Gabelhornträger (Antilocapridae).[11] Die nähere Verwandtschaft des Gabelbocks war lange Zeit vollkommen unklar. Obwohl er schon frühzeitig in eine eigene Familie gestellt wurde, wurde er von manchen Autoren bis in die 1980er Jahre als Teil der Hornträger (Bovidae) betrachtet und dort der eigenen Unterfamilie Antilocaprinae zugeordnet. Auf der Basis morphologischer Daten wurde der Gabelbock ursprünglich als Schwesterart der Hirsche (Cervidae) eingeordnet, vor allem aufgrund des Aufbaus des Tränenbeines, der sich bei den beiden Gruppen ähnelt und sie von allen anderen Paarhufern abgrenzt.[12] Genetische Untersuchungen legten dagegen ein Schwestergruppenverhältnis der Moschustiere (Moschidae) und der Hirsche nahe, während der Gabelbock nicht mehr in die nähere Verwandtschaft der Hirsche gestellt wurde.[12][13] Karyologische Analysen ergaben, dass der Gabelbock mit seinen aus 58 Chromosomen bestehenden Genom einen vergleichsweise ursprünglichen Zustand innerhalb der Stirnwaffenträger (Pecora) repräsentiert. Obwohl die Giraffen (Giraffa) mit nur 30 Chromosomen zahlreiche Verschmelzungen im Genom aufweisen, wird eine nahe Verwandtschaft dieser beiden Taxa an der Basis der Pecora angenommen. Die Struktur des X-Chromosoms deutet dabei darauf hin, dass der Gabelbock die Schwesterart der Giraffen sein könnte, alternativ stellen sie – wie hier im Kladogramm dargestellt – die Schwesterart aller übrigen Pecora dar.[14] Die Verschiebung der Antilocapridae an die Basis der Stirnwaffenträger zeigt auf, dass die Ausbildung der mit Keratin überzogenen, knöchernen Hörner eine echte konvergente und nicht nur parallele Entwicklung zu den Hörnern der Boviden ist. Zudem nehmen die Antilocapridae und somit auch der Gabelbock dadurch eine Schlüsselstellung für das Verständnis der Entwicklung der Stirnwaffen bei den Wiederkäuern ein.[3]

Antilocapra

Die Gabelhornträger stellen heute eine monotypische Familie mit dem Gabelbock als einzigem Mitglied dar. Fossil sind aber wenigstens 20 Gattungen mit insgesamt rund 60 Arten bekannt, die alle aus Nordamerika stammen. Der phylogenetische Vorgänger der Antilocapridae ist unbekannt, dürfte aber in asiatischen Paarhufern des Oligozän zu finden sein. Die Unterscheidung der einzelnen Mitglieder der Gabelhornträger erfolgt überwiegend anhand der unterschiedlich gestalteten Hornschäfte, weniger anhand schädel- und skelettanatomischer Merkmale. Da die letzte Revision der Familie im Jahr 1937 erfolgte, wird eine neue angemahnt, die auf Gattungs- und Artebene durchgeführt werden sollte und bei der ebenfalls Merkmale des Skelett- und Schädelbaus mit einzubeziehen wären.[3]

Die Familie teilt sich in zwei Hauptlinien auf. Zur einen gehören die kleineren „Merycodontinae“, die nur 7 bis 10 kg schwer wurden, aber möglicherweise eine paraphyletische Unterfamilie darstellen. Charakterisiert sind sie neben der allgemein geringeren Körpergröße durch schmalere und runde Hornschäfte mit einem oder mehreren knöchernen Graten oder Ringen an der Basis, durch das Vorhandensein der oberen Eckzähne und durch rudimentäre, seitliche Zehen an den Vorderfüßen. Sie kamen vor allem im Unteren Miozän bis zum Beginn des Oberen Miozän vor etwa 20,6 bis 10,3 Millionen Jahren vor. Die spätesten Formen überlappen zeitlich ein wenig mit den Antilocaprinae, der stammesgeschichtlich jüngeren Gruppe mit durchschnittlich größeren Tieren (30 bis 80 kg), die erstmals im Mittleren Miozän vor rund 15 Millionen Jahren auftritt. Deren besondere Merkmale umfassen seitlich abgeflachte Hornschäfte ohne basale Grate, eine Keratinhülle um die Hörner, eine hochkronige Bezahnung und fehlende Seitenstrahlen an den Vorderfüßen. Zudem sind die Metapodien deutlich verlängert und erinnern an jene der Hirsche. Innerhalb der Antilocaprinae bestehen ebenfalls einige Entwicklungslinien. So stellen die Ilingocerotini Formen mit gedrehten Hörnern dar, die entfernt an jene der Kudus erinnern. Die Stockocerotini kennzeichnen wiederum vier bis sechs knöcherne Hornschäfte, die oberhalb der Orbita wachsen. Die Antilocaprini werden durch den Gabelbock repräsentiert. Dessen nächste verwandte Gattung stellt hier Texoceros dar, der im Gegensatz zum Gabelbock einen gegabelten knöchernen Hornschaft besitzt.[15][3] Innerhalb der Gattung Antilocapra ist Antilocapra pacifica die Schwesterart, welche 1991 anhand mehrerer Hornschäfte und Schädelfragmente beschrieben worden war. Gefunden wurden diese im Contra Costa County im US-Bundesstaat Kalifornien, sie können aber nur allgemein in das Pleistozän datiert werden. Die Vertreter dieser Art erreichten etwa die Größe des heutigen Gabelbocks, besaßen aber ausgeprägtere Hörner.[16]

Vom heutigen Gabelbock können je nach Lehrmeinung vier bis sechs Unterarten unterschieden werden, von denen der Status der vier folgenden unumstritten ist:[11]

Die manchmal ebenfalls als Unterarten geführten Antilocapra americana anteflexa und Antilocapra americana oregona sind dagegen wohl Synonyme der Unterart Antilocapra americana americana. Die Erstbeschreibung der Art erfolgte 1815 durch George Ord als Antilope americanus[1] anhand von Individuen aus den Ebenen und dem Hochland entlang des Missouri River in den Vereinigten Staaten.[11] 1818 richtete Ord zudem die Gattung Antilocapra ein und ordnete dieser Antilocapra americana als Typusart zu.[1]

Die einst artenreiche Familie der Gabelhornträger trat erstmals im Unteren Miozän vor rund 20 Millionen Jahren in den Gras- und Savannenlandschaften des westlichen Nordamerika auf. Die Tiere waren schon relativ gut entwickelt und mit ihrem grazilen Körperbau und langen Gliedmaßen von Beginn an an die offenen Landschaften angepasst, sie stellten somit schnellläufige (cursoriale) Paarhufer dar. Hinweise auf phylogenetische Vorgänger gibt es nicht. Da aus Nordamerika keine älteren Stirnwaffenträger bekannt sind, wanderten die Vorläufer der Gabelhornträger möglicherweise aus Eurasien ein. Als nächster Verwandter kann Amphimoschus angesehen werden, der aus zahlreichen Fundstellen des Unteren und Mittleren Miozäns Europas belegt ist. Dieser besaß allerdings keine Stirnwaffen, die Übereinstimmungen zu den Gabelhornträgern finden sich überwiegend im Bau des Innenohrs.[17] Unter den Gabelhornträgern Nordamerikas erschienen zuerst die kleinen „Merycodontinae“, deren Hörner noch mit Haut überzogen waren. Der früheste bekannte Vertreter war Paracosoryx mit einem sehr langen, weit oben gegabelten Gehörn. Andere frühe Formen werden durch Meriamoceros repräsentiert, das kurze, am oberen Ende zu kleinen Schaufeln umgebildete Hörner aufwies. Recht erfolgreich war Ramoceros, das erst vor 10 Millionen Jahren verschwand und ein vielfach gegabeltes, den Geweihen der Hirsche ähnelndes Gehörn besaß. Dieses war aber teilweise asymmetrisch aufgebaut, so dass eine Seite länger war als die andere. Die Typusform der frühen Antilocapridae stellte Merycodus dar, dessen Besonderheit ein gegabelter Hornschaft mit zwei gleich langen Sprossen ist. Da etwas mehr als die Hälfte der aufgefundenen Schädel hornlos ist, gehen Wissenschaftler davon aus, dass weibliche Tiere nicht über Hörner verfügten. Als einer der ersten Vertreter der Gabelhornträger ist Merycodus auch im nördlichen Teil des heutigen Mexikos nachgewiesen.[18] Trotz ihres Vorkommens in offenen Landschaften ernährten sich die frühen Gabelhornträger weitgehend von gemischter Pflanzenkost.[15][3][9]

Im Mittleren Miozän vor rund 15 Millionen Jahren sind dann mit Plioceros, ein kurzhalsiges Tier mit sehr breiten und kurzen Hörnern, die ersten Vertreter der Antilocaprinae mit Keratin überzogenen Hornbildungen nachgewiesen. Plioceros war dabei noch relativ klein, besaß aber schon extrem hochkronige Zähne. Es stellt zudem eine der am weitesten verbreiteten Angehörigen der Gabelhornträger dar und ist von der Westküste des nordamerikanischen Kontinentes bis nach Florida an der Ostküste überliefert. Ein bedeutendes Fundgebiet ist zudem die Ash-Hollow-Formation im Mittleren Westen. Im Oberen Miozän und im Pliozän erreichten die Antilocaprinae ihre größte Vielfalt, sie sind zu jener Zeit mit 9 Gattungen und 30 Arten bekannt. Osbornoceros aus dem Oberen Miozän sah dabei dem heutigen Gabelbock schon ähnlich, besaß aber eher gewundene Hörner. Er gehörte weiterhin zu den ersten Vertretern, die vermehrt hartes Gras zu sich nahmen.[15][3][9]

Im Verlauf des Pliozän begann langsam der Niedergang der Gabelhornträger. Allerdings erschienen zu dieser Zeit mit den Stockocerotini eine Gruppe gedrungener Tiere, die sich dem eiszeitlichen Klima anpassten und die eine heute ausgestorbene Seitenlinie repräsentieren. Der älteste Vertreter aber war Hexameryx, der durch sechs weit zueinander divergierende Hornschäfte, drei an jeder Kopfseite, geprägt war, allerdings bisher nur aus dem Oberen Miozän von Florida bekannt ist.[19] Capromeryx stellt weiterhin eine Form dar, die sich durch eine markante Körpergrößenreduktion auszeichnete. Im Durchschnitt waren Individuen des Oberen Pleistozän rund 14 bis 30 % kleiner als solche des Unteren. Der Verzwergungsprozess verlief dabei isometrisch.[20] Die jeweils zwei Hornschäfte je Kopfseite standen bei Capromeryx sehr eng beieinander und waren Untersuchungen zufolge wohl zusammen von einer Keratinschicht umgeben. Dabei gehört die Gattung zu den häufig aufgefundenen Gabelhornträgern sowohl in den heutigen USA als auch im angrenzenden Mexiko.[21][22] In die gleiche Entwicklungslinie sind auch Hexobelomeryx und Hayoceros zu stellen, die zu den am stärksten angepassten Grasfressern innerhalb der Gabelhornträger gehörten. Das für die Gruppe namengebende Stockoceros wies insgesamt vier gleich lange Hornschäfte, die von beiden Geschlechtern getragen wurden, und weniger hypsodonte Backenzähne auf, es verblieb weitgehend bei der gemischten Pflanzenkost.[23] Zudem gehört Stockoceros zu den spätesten Vertretern der fossilen Gabelhornträger und trat etwa zeitgleich mit den ersten Angehörigen der heutigen Gattung Antilocapra auf. Allein 7 Teilskelette, 55 Schädel und fast 800 weitere Skelettreste sind von dieser fossilen Gattung aus der Papago Springs Cave nahe Sonoita in Arizona bekannt.[24] Während am Ende der Letzten Kaltzeit all diese Arten ausstarben, überlebte der Gabelbock, den es auch bereits im Pleistozän gegeben hatte, als einziger.[15][3]

Für die Indianer der Prärie waren Gabelböcke wertvolle Fleischlieferanten. Da sie ein überaus häufiges Wild waren – noch 1800 gab es etwa 40 Millionen Einzeltiere in der Prärie – spielten sie im indianischen Alltag oft eine große Rolle. Die Westlichen Shoshone kannten eine zeremonielle Gabelbockjagd, die von einem Schamanen eingeleitet wurde. Wie die Bisonjagd hatte die Jagd auf Gabelböcke eine religiöse Dimension. Eine Gruppe Jäger trieb die Tiere mit Hilfe eines Feuers in die Hände einer zweiten Gruppe Jäger, in die Richtung eines Flusses oder in einen zuvor vorbereiteten Korral, ein Fanggehege für wilde Tiere. Die Nördlichen Shoshone hingegen streiften sich Felle von Gabelböcken über und pirschten sich so getarnt möglichst nah an eine Herde heran. Auch nach der Verfügbarkeit des Pferdes war die Gabelbockjagd eine anspruchsvolle Herausforderung, da Gabelböcke schneller als Pferde zu laufen vermögen.

Die Lakota begehrten die Gabelböcke nicht nur wegen ihres Fleisches, sondern auch wegen ihrer Felle, die sie gerne für die Herstellung von Kleidung verwendeten. Den Bestand des Gabelbocks konnten die amerikanischen Ureinwohner mit ihren Jagdmethoden jedoch nicht in nennenswerter Weise beeinträchtigen.

Den europäischen Kolonisten war der Gabelbock lange Zeit unbekannt, bis die Art von Lewis und Clark auf ihrer Expedition (1804–1806) beschrieben wurde. In jener Zeit waren die Grasländer des nordamerikanischen Westens überreich an Großwild wie Bisons und Gabelböcken.

Nach der großflächigen Besiedlung Nordamerikas durch weiße Siedler glich das Schicksal des Gabelbocks dem des Amerikanischen Bison. Sie wurden zunächst wegen ihrer Felle und ihres Fleisches geschossen, später nur noch zum Sport bzw. aus Vergnügen. Aus den fahrenden Zügen entlang der Eisenbahnstrecken schossen Reisende Tausende von Gabelböcken ab, deren Kadaver zu beiden Seiten der Bahnlinien verwesten. Bis 1920 war die Bestandszahl durch unkontrollierte Jagd auf nur noch 20.000 Tiere gesunken. Erst danach wurden Schutzmaßnahmen erlassen, weshalb es heute wieder eine Million Gabelböcke in den USA und in Kanada gibt, so dass die Art als Ganzes nicht als gefährdet gilt.

In Mexiko hat sich der Bestand dagegen nie erholen können. Dort gibt es auch heute nur wenig mehr als 1000 Tiere. Folgerichtig listet die internationale Organisation zur Koordinierung des Naturschutzes (IUCN) die beiden mexikanischen Unterarten als bedroht. Dies sind der Sonora-Gabelbock (A. a. sonoriensis) und der Baja-California-Gabelbock (A. a. peninsularis). Letzterer ist nur auf der Halbinsel Baja California beheimatet und wird als stark bedroht geführt.

Gabelböcke sind für einige bedeutende Infektionskrankheiten der Paarhufer empfänglich. So bilden sie ein Erregerreservoir für das bösartige Katarrhalfieber, BVD/MD und die Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD). Daneben besteht eine hohe Empfindlichkeit für Milzbrand, Tollwut und diverse Parasitosen.

Als Beitrag zur Bestandssicherung werden Gabelböcke auch als Zootiere gehalten. Ihre Schreckhaftigkeit und ihre Neigung zur Panik im Umgang mit Menschen stellt hier ein besonderes tierpflegerisches Problem dar. Bei Unterschreitung der Fluchtdistanz reagieren die Tiere nicht selten mit einem kompromisslosen Angriff, der infolge der wirkungsvoll eingesetzten Hörner durchaus gefährlich werden kann. Jegliche Anwendung von Zwangsmaßnahmen kann zu Selbsttraumatisierung oder Stressmyopathie führen. Körperliche Untersuchungen können daher nur unter Sedation oder Narkose erfolgen. Eine wirkungsvolle Narkose ist dabei nur durch hochpotente Betäubungsmittel vom Morphintyp erreichbar. Gabelböcke lassen sich im Zoo nur schwer mit anderen Huftierarten vergesellschaften, schon das Eingliedern handaufgezogener, männlicher Tiere kann aufgrund ihrer Aggressivität zu Konflikten führen. Auch das natürliche Sprung- und Schwimmvermögen der Gabelböcke muss bei der Einrichtung des Geheges berücksichtigt werden. Anders als in freier Wildbahn beträgt die Lebenserwartung der Tiere in Gefangenschaft bis zu 17 Jahre.

Der Gabelbock (Antilocapra americana), auch als Gabelhornantilope, Gabelantilope, Gabelhorntier, Gabelhornträger oder Pronghorn bekannt, ist ein nordamerikanischer Wiederkäuer der Prärie. Obwohl seine Gestalt an die Antilopen Afrikas und Asiens erinnert, gehört er nicht zu deren Familie der Hornträger. Er bildet die heute monotypische Familie der Gabelhornträger (Antilocapridae) als ihr einziger rezenter Vertreter.

Di goobelroom (Antilocapra americana) as en kwetjkauer, di uun Nuurdameerikoo lewet. Hi liket en antiloop, as diar oober ei nai mä. Hi as di iansagst slach uun det famile Antilocapridae.

Di goobelroom (Antilocapra americana) as en kwetjkauer, di uun Nuurdameerikoo lewet. Hi liket en antiloop, as diar oober ei nai mä. Hi as di iansagst slach uun det famile Antilocapridae.

Teotlalmazatl (Antilocapra americana, caxtillantlahtolli:Berrendo) ce chichini yolcatl ochanti ipan teotlalli ahnozo ixtlahuatl.

Η αντιλοκάπρα είναι μηρυκαστικό θηλαστικό της οικογενείας των Αντιλοκαπριδών, της οποίας αποτελεί το μοναδικό σωζόμενο μέλος. Απαντά αποκλειστικά στα ηπειρωτικά των ΗΠΑ και σε μικρό τμήμα του Καναδά και του Μεξικού. Η επιστημονική ονομασία του είδους είναι Antilocapra americana και περιλαμβάνει 5 υποείδη.[1]

Παρόλο που, υπό την στενή έννοια του όρου (sensu stricto), δεν είναι αντιλόπη, η αντιλοκάπρα καταλαμβάνει παρόμοιο οικολογικό θώκο με τις αντιλόπες του Παλαιού Κόσμου, μοιάζει με αυτές και, κάποιες από τις λαϊκές της ονομασίες στις περιοχές όπου απαντά, συμπεριλαμβάνουν τον συγκεκριμένο όρο (βλ. και Ονοματολογία).

Η (νεο-)λατινική ονομασία του γένους, Antilocapra, έχει ελληνική προέλευση, αποτελούμενη από τα επί μέρους συνθετικά antilo[pe] «αντιλόπη» + capra «αίγα» [6] Ο όρος americana στην επιστημονική ονομασία του είδους, παραπέμπει στην ήπειρο, από όπου κατάγεται και διαβιοί το θηλαστικό.

Στην Βόρεια Αμερική, η αντιλοκάπρα αποκαλείται με την λαϊκή ονομασία pronghorn, εκ των συνθετικών prong «περόνη, ακίδα, σουβλί» + horn «κέρατο», δηλαδή «(αυτός που έχει) ακιδωτά, σουβλερά κέρατα». Η ονομασία παραπέμπει στις χαρακτηριστικές μυτερές διακλαδώσεις των κεράτων του θηλαστικού.

Άλλες τοπικές ονομασίες με τις οποίες απαντά η αντιλοκάπρα, είναι: prong buck, pronghorn antelope, cabri ή απλώς antelope, επειδή το θηλαστικό αποτελεί το οικολογικό «ισοδύναμο» των αντιλοπών του Παλαιού Κόσμου, στην Αμερική.[7] Επίσης, στο Μεξικό αποκαλείται berrendo.

Η αντιλοκάπρα αποτελεί μονοτυπικό γένος (Antilocapra) εντός της οικογενείας των Αντιλοκαπριδών (Antilocapridae), επίσης μονοτυπικής, εντός της τάξης των Αρτιοδακτύλων. Αποτελούσε και εξακολουθεί να αποτελεί «γρίφο» για τους συστηματικούς ταξινομικούς και, μέχρι την δεκαετία του 1980 περιλαμβανόταν στην οικογένεια Bovidae. Μελέτη του 2005, τοποθέτησε την οικογένεια Αντιλοκαπρίδες ως «αδελφικό» taxon της οικογενείας των Ελαφιδών (Cervidae), με βάση την συγκριτική ανατομική του δακρυϊκού οστού των μελών τους.[8] Κατοπινές γενετικές μελέτες τοποθέτησαν τις Αντιλοκαπρίδες πλησιέστερα στην οικογένεια των Μοσχιδών (Moschidae).[9] Καρυολογικές αναλύσεις, ωστόσο, έδειξαν μεγάλη συγγένεια με την οικογένεια των Καμηλοπαρδαλιδών (Giraffidae) εντός της υποτάξης των Pecora, ιδιαίτερα με την καμηλοπάρδαλη, βάσει της δομής του φυλογενετικού χρωμοσώματος Χ.[10]. Πάντως, πολλοί είναι εκείνοι που υποστηρίζουν ότι η οικογένεια των Αντιλοκαπριδών εξελίχθηκε εντελώς ανεξάρτητα από τις προαναφερθείσες συγγενικές οικογένειες.[11]

Η αντιλοκάπρα απαντά αποκλειστικά στην Βόρεια Αμερική, ως ενδημικό θηλαστικό των περιοχών όπου κατανέμεται. Η εξάπλωσή της περιλαμβάνει έναν (1) πυρήνα στα δυτικοκεντρικά των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών, με περιφερειακές θέσεις στα σύνορα με τον Καναδά, τις ΝΔ. ΗΠΑ και το Β. Μεξικό.

Οι αντιλοκάπρες έγιναν γνωστές στον επιστημονικό κόσμο από την Αποστολή των Λιούις και Κλαρκ (The Lewis and Clark Expedition) μεταξύ 1804 και 1806 και, συγκεκριμένα από την περιοχή των ΗΠΑ που, σήμερα, είναι γνωστή ως Νότια Ντακότα. Το φάσμα κατανομής εκτείνεται από τα νότια των πολιτειών Σασκάτσουαν και Αλμπέρτα του Καναδά, στις πολιτείες μεταξύ Μοντάνα και Μινεσότα στα βόρεια των Ηνωμένων Πολιτειών, μέχρι την Αριζόνα, το Β. Τέξας, τις ακτές της Ν. Καλιφόρνιας και την βόρεια Μπάχα Καλιφόρνια Σουρ στα νότια, ενώ μέσα στο Μεξικό περιλαμβάνονται οι περιοχές Β. Σονόρα και Σαν Λουίς Ποτοσί.

Το 1959 έγινε εισαγωγή μικρού πληθυσμού στην Χαβάη, αλλά το 1983, μόνον 12 άτομα είχαν απομείνει εκεί και ο πληθυσμός όδευε προς εξαφάνιση.[12]

Η αντιλοκάπρα διαβιοί κυρίως στα ανοικτά, εκτεταμένα, άδενδρα εδάφη τύπου chaparral και στα λιβάδια μεταξύ 900 και 1.800 μ., αν και μπορούν να παρατηρηθούν μέχρι τα 3.050 μ.,[12] με τους πυκνότερους πληθυσμούς σε περιοχές που δέχονται 25-40 εκ. βροχής ετησίως, περίπου. Το νότιο τμήμα του εύρους κατανομής τους κυριαρχείται κυρίως από άνυδρα βοσκοτόπια και ανοικτά λιβάδια. Τον χειμώνα, ιδιαίτερα οι βόρειοι πληθυσμοί εξαρτώνται σε μεγάλο βαθμό από την παρουσία θάμνων με τους οποίους τρέφονται, γι’ αυτό και κινούνται κατά μήκος των κορυφογραμμών που τις σαρώνουν ισχυροί άνεμοι έτσι, ώστε η βλάστηση να καθαρίζεται από το χιόνι, αν και οι αντιλοκάπρες μπορούν να σκάψουν με τις οπλές τους για να αποκαλύψουν τα φυτά.[13][14] Feldhamer et al

Στην περιοχή της πολιτείας του Όρεγκον, οι αντιλοκάπρες περιπλανώνται στις ανοικτές εκτάσεις που βρίθουν από τους αρωματικούς θάμνους της Artemisia tridentata ενώ, περιστασιακά, απαντούν σε εδάφη με διάσπαρτα κωνοφόρα Juniperus occidentalis και Pinus ponderosa. Την άνοιξη απαντούν και σε εδάφη με αγρωστώδη τύπου Bromus tectorum. Στα ίδια ενδιαιτήματα, η παρουσία ύδατος, -είτε ελεύθερου είτε μέσα στα σαρκώδη φυτά- αποτελεί καθοριστικό παράγοντα για τις εποχικές μετακινήσεις του θηλαστικού. Αυτός είναι ο λόγος που, κατά την διάρκεια του φθινοπώρου και του χειμώνα σε περιόδους με αρκετές βροχοπτώσεις, οι αντιλοκάπρες παρατηρούνται σε ξερικά εδάφη. Αντίθετα, κατά τη διάρκεια των θερμών εποχών και στις περιόδους παρατεταμένης ξηρασίας, απαντούν σε πεδινές περιοχές όχι περισσότερο των 3 χλμ. από κάποια πηγή νερού. Γενικά αποφεύγουν εδάφη με υψηλή βλάστηση (>70 εκ.), όπως και τις εκτεταμένες άγονες και ημιερημικές περιοχές.[4]