en

names in breadcrumbs

Observed North American predators include sharp-shinned hawks (Accipiter striatus) on adults and Tamiasciurus species, gray jays (Perisoreus canadensis), and Steller's jays (Cyanocitta stelleri) on eggs and nestlings. Likely predators include other raptors that specialize on birds: Cooper's hawks (Accipiter cooperi), merlins (Falco columbarius), peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus), and northern shrikes (Lanius excubitor). American kestrels (Falco sparverius, sharp-shinned hawks (Accipiter striatus), and northern pygmy owls (Glaucidium gnoma) have all been observed attacking red crossbill decoys. Eurasian predators are likely to be similar: bird specialist raptors, corvids, and squirrels.

Known Predators:

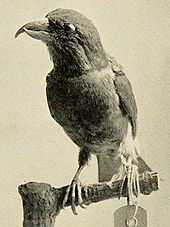

Red crossbills are medium-sized finches with distinctive, curved mandibles that are crossed at their tips. Males are slightly larger than females (males: 23.8 to 45.4 g, females: 23.7 to 42.4 g). Males are a deep red color, sometimes reddish yellow, with dark brown flight and tail feathers. Females are olive to gray or greenish yellow on the breast and rump with dark brown flight and tail feathers. Immature birds are overall streaked with brown on a lighter background. The tail is notched. Red crossbills don't undergo any seasonal changes in plumage. They are easily distinguished from other species by their crossed bills, except for other Loxia species. In North America, white-winged crossbills (Loxia leucoptera) are distinguished by their white wing bars.

Red crossbills show a striking amount of geographic variation in body size and bill size and shape, despite the fact that populations regularly co-occur and that all populations range widely outside of the breeding season. Morphologies are also associated with distinctive call types. Some researchers have proposed up to 8 North American cryptic species based on call type and associated morphology. Similar levels of variation and tight association of call types and foraging morphology is observed in the Palearctic. Some evidence of reproductive isolation has been reported in the Palearctic, but mitochondrial DNA sequence data does not support the notion of reproductive isolation, instead finding that mitochondrial haplotypes mixed at continental scales.

Basal metabolic rate of captive red crossbills was estimated at 19% higher than expected for their body size.

Range mass: 23.7 to 45.4 g.

Range length: 14 to 20 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger; sexes colored or patterned differently; male more colorful

Information on lifespan in the wild is not reported in the literature. Captive red crossbills can live up to 8 years in the wild. Females may suffer higher predation rates because of the extended periods of time they spend on the nest.

Range lifespan

Status: captivity: 8 (high) years.

Red crossbills are found almost exclusively in mature, coniferous forests, including spruce (Picea), fir (Abies), hemlock (Tsuga), and pine (Pinus) forests. They can also be found in mixed decidous-coniferous forests, provided there are ample supplies of conifer seeds to eat. Specific "call types" of red crossbills are associated with 1 or more conifer species. For example, two large-billed types of red crossbills in western North America are found closely associated with the large cones of Engelmann's spruce (Picea engelmanni), ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), and table mountain pine (Pinus pungens). Another, eastern type associates mainly with Newfoundland black spruce (Picea mariana). Small-billed red crossbills associate with conifers with smaller cones, such as hemlocks (Tsuga) and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga). This close association between call types and conifer species has led to the description of many subspecies and speculation about strong selection of food types on bill-shape and subsequent reproductive isolation through vocalizations (call types). However, a study of mitochondrial DNA showed no evidence of reproductive isolation among subspecies or call types. Morphological differences among populations specialized to particular conifer species may be the result of rapid local adaptations.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: forest

Red crossbills are found throughout the northern hemisphere. They are not migratory, but wander widely outside of the breeding season. Occasional irruptions may involve thousands of birds traveling to areas outside of their normal range. In the Americas, red crossbills are found in northern boreal and high altitude coniferous forests from coastal Alaska throughout much of Canada to the maritime provinces and south to northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine. They are found in appropriate habitat throughout the Sierra, Rocky Mountain, and Sierra Madre mountain ranges, as well as smaller mountain ranges in Baja California, Honduras, Nicaragua, Belize, and the Mexican volcanic belt. Small, disjunct breeding populations are found in the Appalachian Mountains and occasional breeding populations are found in appropriate habitat outside of their typical range. In the Palearctic, red crossbills are found from the British Isles across northern Europe, Russia, and Asia to the Kamchatka Peninsula and Japan. They are also found in appropriate habitat in mountain ranges, including the Alps, Pyrenees, Himalayas, Vietnam, the Philippines, and into the Atlas Mountains of northern Africa. They co-occur with other Loxia species in Scotland (Loxia scotica), Scandinavia and western Russia (Loxia pytyopsittacus), and North America (Loxia leucoptera).

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native ); palearctic (Native )

Other Geographic Terms: holarctic

Red crossbills feed exclusively on conifer seeds. Populations, or call types, may have specialized bill morphologies that make them most efficient at extracting the seeds from cones of particular conifer species. Red crossbills travel in feeding flocks that help individuals take best advantage of locally variable conifer seed crops. Flocking is thought to help these crossbills avoid predation while also assessing the best areas for foraging. Red crossbill calls and calling rates transmit information on the availability of food. Flying birds join foraging flocks when the foraging birds are calling. However, call rate increases among foraging birds as they spend more time feeding and, perhaps, begin to have less success in finding food. As the call rate reaches a crescendo, the flock departs to look for another foraging opportunity. The calls of foraging birds do not attract flying groups of another call type, however, which is consistent with their specialization on different conifer species.

Red crossbills feed mainly on conifer cones still attached to trees, although they will also hold unattached cones in their feet. They use their peculiar mandibles to bite between cone scales so that, as they bite, the lower mandible opens the scale and exposes the conifer seed. In particularly tough cones they may have to bite several times or twist with their head before they can reach the conifer seed with their tongue. Their "crossed" mandibles are essential for this task and allow them to exploit a niche not otherwise exploited among seed-eating birds. Once they expose a conifer seed, they remove the seed coat with their tongue and mandible and either swallow small seeds whole or crush larger seeds. Red crossbills take grit or sand into their crop to help with processing their seed diet.

Plant Foods: seeds, grains, and nuts

Primary Diet: herbivore (Granivore )

Red crossbills are important seed predators of conifers across their range and regional populations are highly specialized to extract seeds of particular conifer species. They are parasitized by biting lice (Mallophaga).

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Red crossbills are interesting and integral parts of the coniferous, forested habitats in which they live. They are a fascinating example of extreme specialization to a food type and subsequent rapid morphological adaptation.

Positive Impacts: research and education

Red crossbills do not adversely affect humans. Their predation on conifer seeds could conceivably impact forestry practices, but these impacts are negligible.

Red crossbills have a large range and large population numbers, they are not currently considered threatened. There were large reductions in the numbers of red crossbills in areas logged during the 19th and 20th centuries, but some of those populations may have rebounded as forests re-grew. A combination of nomadism, adaptation to cold environments, high reproductive rate with abundant food supply, and early sexual maturity make red crossbills especially good at responding to variation in cone crop availability across a landscape. Their populations can rebound quickly when food resources are available. Red crossbills are frequently killed by cars when they take salt and sand off of roads.

US Migratory Bird Act: protected

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Red crossbills are divided into discrete "call types" that correspond to bill morphologies that allow them to specialize on the conifer seeds of particular conifer species. Young red crossbills of all call types make similar sounds during the nestling and fledgling stages. By the time they reach independence, however, they are using the specific call type of their parents. Mated pairs imitate each other to produce identical flight calls to remain in contact with each other. Flight calls are described as a "chip chip chip." Males sing from perches near their nest, songs are described as a buzzing "whit-whit" or "zzzt zzzt," although these songs also vary among call types. Other vocalizations used include alarm or distress calls, and excitement, threat, chitter, or courtship calls.

Communication Channels: acoustic

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Red crossbills are monogamous and seem to stay in pairs throughout the year. Pairs use identical flight calls and seem to remain together throughout the year, although there is no direct evidence that year-round pairs are also mates in breeding season. Males sing from perches and make display flights to attract females. Males are aggressive towards other males during the breeding season. Courtship involves feeding the female and billing (grabbing each other by the bill). Males then accompany females constantly after courtship and during the period of egg-laying, presumably to prevent extra-pair copulations.

Mating System: monogamous

Many aspects of breeding phenology and behavior are strongly influenced by the availability of food. Throughout their range, red crossbills may be found breeding in almost every month, although local populations breed seasonally. Some populations, given enough conifer seed resources, can breed for up to 9 months out of the year. In North America eggs have been observed from December to September. Mated pairs select a nest site, usually an interior, densely covered branch of a conifer tree from 2 to 20 meters above ground. Males may contribute nesting materials, but females build the nest. Nests are constructed of conifer twigs lined with grasses, lichen, conifer needs, shredded bark, and feathers. Females lay 3 eggs typically, 1 each day, with incubation starting at the last egg laid, unless the weather is cold. Females incubate eggs for 12 to 16 days and brood nearly continuously for 5 days after hatching. Hatchlings go into torpor during brief absences of the female from the nest. Both hatching and fledging may be delayed by cold weather or lack of food. Young fledge at 15 to 25 days after hatching, depending on the availability of food. After fledging, the young follow their parents around (or only the male parent if the female lays a second clutch) and continue to beg for food and practice obtaining seeds from conifer cones. Parents sometimes feed their young for up to 33 days after they have fledged. Young red crossbills may become sexually mature even before they have taken on their adult plumage, as early as 100 days after hatching.

Breeding interval: Red crossbills can lay several clutches in a year, usually 2 to 4, depending on food availability. Pairs with access to abundant food resources can lay a second clutch while they are still feeding previous fledglings.

Breeding season: Red crossbill breeding season varies regionally and with food availability.

Range eggs per season: 2 to 6.

Average eggs per season: 3.

Range time to hatching: 12 to 16 days.

Range fledging age: 15 to 25 days.

Range time to independence: 48 to 58 days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 100 (low) days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 100 (low) days.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

Young red crossbills hatch in an altricial state, with no down. Females incubate and brood the young and males help to defend small foraging territories, provide some courtship food to the female, and feed hatchlings and fledglings until they become proficient at extracting conifer seeds from cones.

Parental Investment: altricial ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Male, Female)

A medium-sized (5 ¼ -6 ½ inches) finch, the Red Crossbill is most easily identified by its black wings, short black tail, and oddly-shaped bill. Males’ bodies may be bright red, yellow, or a mixture of both, although the cause of this variation in color is more related to the timing of the individual’s yearly molt than to heredity. Female Red Crossbills are streaky brownish-yellow on the back, head, and face. The Red Crossbill inhabits a large area of the Northern Hemisphere. In the New World, this species breeds across southern Alaska, southern Canada and the northern United States. This species’ range extends south at higher elevations as far as North Carolina in the east and southern Arizona in the west. Other populations occur in the mountains of Mexico and Central America south to Nicaragua. In the Old World, this species breeds across northern portions of Eurasia, with isolated populations at higher elevations as far south as North Africa, Vietnam, and the Philippines. Red Crossbills wander widely during winter, and in some years northern populations may move south in large numbers as far as the southeastern U.S. and southern Europe. Red Crossbills inhabit evergreen forests with trees that produce cones. This species almost exclusively eats seeds taken from these cones, and its strangely-shaped bill is specially adapted to cracking open cones to extract seeds. This species eats seeds from a number of kinds of evergreen trees, including pines, spruces, firs, and hemlocks. In fact, different populations of Red Crossbills often prefer one evergreen tree family over the others, having bills particularly suited to cracking cones produced by that kind of tree. In suitable habitat, Red Crossbills may be observed feeding on cone seeds while perched on branches or hanging upside-down from the cone. In more built-up areas, this species may also visit bird feeders in the company of other finch species. Red Crossbills are most active during the day.

A medium-sized (5 ¼ -6 ½ inches) finch, the Red Crossbill is most easily identified by its black wings, short black tail, and oddly-shaped bill. Males’ bodies may be bright red, yellow, or a mixture of both, although the cause of this variation in color is more related to the timing of the individual’s yearly molt than to heredity. Female Red Crossbills are streaky brownish-yellow on the back, head, and face. The Red Crossbill inhabits a large area of the Northern Hemisphere. In the New World, this species breeds across southern Alaska, southern Canada and the northern United States. This species’ range extends south at higher elevations as far as North Carolina in the east and southern Arizona in the west. Other populations occur in the mountains of Mexico and Central America south to Nicaragua. In the Old World, this species breeds across northern portions of Eurasia, with isolated populations at higher elevations as far south as North Africa, Vietnam, and the Philippines. Red Crossbills wander widely during winter, and in some years northern populations may move south in large numbers as far as the southeastern U.S. and southern Europe. Red Crossbills inhabit evergreen forests with trees that produce cones. This species almost exclusively eats seeds taken from these cones, and its strangely-shaped bill is specially adapted to cracking open cones to extract seeds. This species eats seeds from a number of kinds of evergreen trees, including pines, spruces, firs, and hemlocks. In fact, different populations of Red Crossbills often prefer one evergreen tree family over the others, having bills particularly suited to cracking cones produced by that kind of tree. In suitable habitat, Red Crossbills may be observed feeding on cone seeds while perched on branches or hanging upside-down from the cone. In more built-up areas, this species may also visit bird feeders in the company of other finch species. Red Crossbills are most active during the day.

The red crossbill or common crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) is a small passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. Crossbills have distinctive mandibles, crossed at the tips, which enable them to extract seeds from conifer cones and other fruits.

Adults are often brightly coloured, with red or orange males and green or yellow females, but there is wide variation in beak size and shape, and call types, leading to different classifications of variants, some of which have been named as subspecies. The species is known as "red crossbill" in North America and "common crossbill" in Europe.

Crossbills are characterized by the mandibles crossing at their tips, which gives the group its English name. Using their crossed mandibles for leverage, crossbills are able to efficiently separate the scales of conifer cones and extract the seeds on which they feed. Adult males tend to be red or orange in colour, and females green or yellow, but there is much variation.

The distinctive crossed mandibles eliminate most other species, but this feature is shared by the similar two-barred crossbill, with which it overlaps considerably in range. The two-barred crossbill has two bright white wing bars, while the wings of the red crossbill are entirely brownish-black.

The red crossbill is the only dark-winged crossbill throughout most of its range, but it overlaps at least seasonally with the small ranges of the very similar parrot, Scottish, and Cassia crossbills. These species were formerly considered subspecies of the red crossbill, and though they show very slight differences in bill size and shape, they are very difficult to visually distinguish from the red crossbill and are generally best identified by call. The plumage differences between these four crossbills are negligible, there being more variation between individual birds than between species.[2][3]

Measurements:[4]

Red crossbills breed in a variety of coniferous forests across North America and Eurasia. Its movements and occurrence are linked very closely to the availability of conifer seeds, its primary food source. They typically nest in late summer (June–September) when the seeds of most conifer species mature, but may nest at any time of year if they locate an area with a suitable cone crop.

This species is considered nomadic and highly irruptive, as conifer seed production may vary considerably year to year and birds disperse widely to breed and forage when the cone crop in their particular vicinity fails. In many areas of their range they are considered irregular because they may be present in certain years and not in others. The various types of red crossbill (see Taxonomy and Systematics) prefer different types of conifers, and therefore may differ in the regularity, timing, and direction of their irruptions. A few populations, such as the Newfoundland crossbill (North American type 8), are resident and do not undertake significant movements. When they are not breeding, the various types of red crossbill may flock together, and may also flock with other species of crossbill.[3][5]

Red crossbill irruptions in the British Isles occur very infrequently, and were remarked upon by writers dating back to the 13th century. These irruptions led in the twentieth century to the establishment of permanent breeding colonies in England, and more recently in Ireland. The first known irruption, recorded in England by the chronicler Matthew Paris, was in 1254; the next, also in England, appears to have been in 1593 (by which time the earlier irruption had apparently been entirely forgotten, since the crossbills were described as "unknown" in England).[6] The engraver Thomas Bewick wrote that "It sometimes is met with in great numbers in this country, but its visits are not regular",[7] adding that many hundreds arrived in 1821. Bewick then cites Matthew Paris as writing "In 1254, in the fruit season, certain wonderful birds, which had never before been seen in England, appeared, chiefly in the orchards. They were a little bigger than Larks, and eat the pippins of the apples [pomorum grana] but no other part of them... They had the parts of the beak crossed [cancellatas] by which they divided the apples as with a forceps or knife. The parts of the apples which they left were as if they had been infected with poison."[7] Bewick further records an account by Sir Roger Twysden for the Additions to the Additamenta of Matt. Paris "that in the apple season of 1593, an immense multitude of unknown birds came into England... swallowing nothing but the pippins, [granella ipsa sive acinos] and for the purpose of dividing the apple, their beaks were admirably adapted by nature, for they turn back, and strike one point upon the other, so as to show... the transverse sickles, one turned past the other."[7]

The red crossbill was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Loxia curvirostra.[8] Linnaeus specified the locality as Europe but this was restricted to Sweden by Ernst Hartert in 1904.[9][10] The genus name Loxia is from Ancient Greek loxos, "crosswise"; and curvirostra is Latin for "curved bill".[11]

The red crossbill is in the midst of an adaptive radiation into the niches presented by the various species of conifer.[12] There are about 10 North American and 18 Eurasian types so far identified,[13] with many known to affiliate with a particular conifer species or a suite of similar conifer species. While each type may be seen to feed on many different conifer species when not breeding, each has optimal breeding success only in a particular type of conifer forest. This isolates the populations against interbreeding, which over time has resulted in their diverging genetically, phenotypically, and even speciating. Birds of all types are essentially identical in appearance but have slight differences in their vocalizations. Typically they are identified by their single note "chip" calls, which they give frequently and which differ considerably between types. Often computer analysis is used to distinguish the call types, but experienced observers can learn to separate the more distinctive ones by ear in the field.[3][14]

The different populations of red crossbill are referred to as "types" because they are differentiated by a phenotypic feature (call note) and not all of them have yet been proven to be genetically distinct. Those populations which have been found to be genetically distinct are considered subspecies. Three populations formerly considered to be subspecies of red crossbill are now recognized by most authorities as full species:

As research into the species has progressed, types are increasingly being found to be genetically distinct and elevated to the subspecies level. It is expected that this trend will continue, and it is also likely that more of these subspecies will eventually be recognized as full species.[3][12][14][15]

Some large-billed, pine-feeding populations currently assigned to this species in the Mediterranean area may possibly be better referred to either the parrot crossbill or to new species in their own right, but more research is needed. These include the Balearic crossbill (L. c. balearica) and the North African crossbill (L. c. poliogyna), feeding primarily on Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis); the Cyprus crossbill (L. c. guillemardi), feeding primarily on European black pine (Pinus nigra); and an as-yet unidentified crossbill with a parrot crossbill-sized bill feeding primarily on Bosnian pine (Pinus heldreichii) in the Balkans. These populations also differ on plumage, with the Balearic, North African and Cyprus subspecies having yellower males, and the Balkan type having deep purple-pink males; this, however, merely reflects the differing anthocyanin content of the cones they feed on, as these pigments are transferred to the feathers.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) {{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) The red crossbill or common crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) is a small passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. Crossbills have distinctive mandibles, crossed at the tips, which enable them to extract seeds from conifer cones and other fruits.

Adults are often brightly coloured, with red or orange males and green or yellow females, but there is wide variation in beak size and shape, and call types, leading to different classifications of variants, some of which have been named as subspecies. The species is known as "red crossbill" in North America and "common crossbill" in Europe.