Behavior

provided by Animal Diversity Web

All bony fishes have lateral lines which can be used to sense pressure and to judge underwater currents and localized movements in the water. The barramundi lateral line extends onto the caudal fin. Barramundi have reflective eyes which allow them to see better in dark conditions. Barramundi also have a sense of smell. Modes of communication in barramundi are poorly understood.

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; vibrations ; chemical

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Conservation Status

provided by Animal Diversity Web

This species is not listed as threatened or endangered by any international organization.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Life Cycle

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Barramundi are serially hermaphroditic, transforming from male to female at three to eight years of age (FAO, 1999; Guiguen, 1993). Moore (1979) suggests some individuals may not undergo this transition, based on a sex ratio of 3.8 males to 1 female.

Color and markings change from juveniles to adults (see "Physical Description").

Development - Life Cycle: metamorphosis

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Benefits

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Although barramundi have not been shown to have any negative impacts, as large piscivores, they have the potential to kill off prey species if introduced into a non-native habitat. Nile Perch (Lates niloticus), are related to barramundi and are responsible for extinctions of native cichlids in Lake Victoria after having been introduced there (Morgan, 2004). According to Morgan et al. (2004), barramundi have limited potential to cause the same problems if introduced into Lake Kununurra in Western Australia.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Benefits

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Barramundi are valuable both as recreational and commercial fish, with a high, fairly stable price (Luna, 2008). They are stocked in lakes and ponds for recreational fishing and are also fished in freshwater creeks and estuaries (Morgan, 2004). Barramundi are heavily farmed in cages, as well as in freshwater and saltwater ponds (Webster, 2002). Worldwide capture peaked in 2000 at 74,207 metric tonnes and declined to 57,074 tonnes caught in 2005 (FAO, 2008; but see Webster, 2002). Aquaculture of barramundi has grown rapidly with 1646 tonnes (4,357,000 USD) produced in 1984, 18,564 tonnes (70,720,000 USD) produced in 1994, and 30,970 tonnes (79,034,000 USD) produced in 2005.

Since it is a white fish with delicate flavor, barramundi is also becoming popular in the United States. As of 2006, the indoor fish farming interest Australis, based in Massachusetts, was shipping 40,000 lbs of fish per week (Pierce, 2006).

Positive Impacts: food

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Associations

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Barramundi are predators and prey (Davis, 1985; Hitchcock, 2007; and Shine, 1986). They help support pelicans and file snakes, among other possible predators, as well as controlling the populations species on which they prey.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Trophic Strategy

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Barramundi are opportunistic predators. They eat microcrustaceans such as copepods and amphipods as juvenile fish under 40 mm. As larger juveniles they eat macrocrustaceans like Penaeidae and Palaemonidae. These crustacean prey are found mainly near the bottom of the water column, so this diet also protects juveniles from most of their predators, which hunt closer to the water surface. Mollusks are consumed to a lesser degree. When barramundi are around 80 mm, they begin to eat macrocrustaceans and pelagic bony fishes. Larger fish have diets of around 80% bony fish. Barramundi swallow their food whole, sucking their prey into their fairly large mouths. Moderate cannibalism is fairly common in barramundi (Davis, 1985).

Animal Foods: fish; insects; mollusks; aquatic crustaceans; other marine invertebrates; zooplankton

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore , Eats non-insect arthropods, Molluscivore )

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Distribution

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Lates calcarifer, known as barramundi, barramundi perch, giant sea perch, or Asian sea bass, is native to coastal areas in the Indian and Western Pacific Oceans. This includes coastal Australia, Southeast and Eastern Asia, and India (Luna, 2008). According to Luna, this distribution is Indo-West Pacific.

According to a 2008 study of barramundi from Burma and Australia, these fish may be two species (Ward, 2008). The study used DNA barcoding: the comparison of a particular locus (600 base pairs of the cytochrome c oxidase I gene) on the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). The study found that there was a significant enough difference in the mtDNA of the fish from the two locations that the species L. calcarifer may be split to take these differences into account. The study only examined fish from two locations, so Ward et al. (2008) recommended further study across the range.

Biogeographic Regions: indian ocean (Native ); pacific ocean (Native )

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Habitat

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Barramundi are catadromous, spending most of their life in fresh water and migrating to salt water in order to breed. Smaller fish are found in rivers and streams and larger fish are found in the ocean and estuaries (Pender, 1996; FAO, 1999). There are exceptions to this patter, however, with populations of all sizes of fish found throughout their natural range. Pender and Griffin confirmed through chemical analysis that there are populations that spend their entire life cycle in salt water, in brackish water, or in fresh water (Pender, 1996). Barramundi can survive in a wide range of salinities, but must be introduced slowly to a new salinity to avoid shock (Webster, 2002). Barramundi generally prefer to hide under logs or other objects.

Barramundi are demersal, meaning they spend most of their time near but not on the bottom of a body of water. They are found at depths of ten to forty meters (Luna, 2008). In barramundi fish farming cages are generally placed two meters below the surface (Webster, 2002).

Range depth: 40 to 10 m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; saltwater or marine ; freshwater

Aquatic Biomes: rivers and streams; coastal ; brackish water

Other Habitat Features: estuarine

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Life Expectancy

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Little is known about longevity of barramundi.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Morphology

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Barramundi are large fish, with a maximum length of over two meters, although they are more commonly around 1.5 meters. Barramundi can have a mass over 55 kilograms. According to the FAO species identification guide, they have a moderately deep, elongate, and compressed body. Barramundi have pointed snouts and large mouths, with jaws extending past the eyes. Nostrils are close together. The dorsal fin is deeply incised, with separate spiny and soft dorsal fins. The spiny dorsal fin has seven to nine spines, and the soft dorsal fin has ten to eleven soft rays. The anal fin has three spines and seven to eight soft rays. Pelvic and pectoral fins are present. These fish have a distinct caudal peduncle, or tail muscle, with a rounded caudal fin. The lateral line extends onto the caudal fin.

The scales of barramundi are firmly fixed and ctenoid. Adult barramundi are silver with darker, olive or blue-gray backs. In turbid (cloudy) water, coloration is darker. Juveniles are brown (sometimes grayish-brown) with three white stripes on the head and scattered white spots elsewhere. The markings can be dimmed or may disappear at will. The fins do not have markings. The eyes are golden-brown with a red reflective glow.

Average mass: 55 kg.

Range length: >2 (high) m.

Average length: 1.5 m.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Associations

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Although barramundi are opportunistic predators (Davis, 1985), they are also a prey species. The patterns present on the scales of juvenile barramundi (FAO, 1999), in combination with the fact that juveniles reside in protected mangroves and swamps (Moore, 1982; Russell, 1985; and FAO, 1999) suggests a need to protect against predators. There are several species that have been found to prey on juvenile barramundi. In an analysis of stomach contents Davis (1985) demonstrated that barramundi over 40 mm consume juvenile barramundi as part of their diet. Australian pelicans (Pelecanus conspicillatus) (Hitchcock, 2007) and file snakes (Acrochordus arafurae) (Shine, 1986) feed on both juvenile and adult barramundi.

Known Predators:

- file snakes (Acrochordus arafurae)

- Australian pelicans (Pelecanus conspicillatus)

- Barramundi (Lates calcarifer)

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Reproduction

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Barramundi spawn seasonally (Moore, 1982). Since they are broadcast spawners (Luna, 2008; Moore, 1982), it can be inferred that there is very little social interaction among individuals. Males and females congregate for the purpose of spawning. Spawning events tend to take place at the mouths of estuaries on or near a full moon, after which tides draw the eggs up into the estuaries (Luna, 2008).

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Lates calcarifer is catadromous; migrating to the mouths of rivers and estuaries in order to breed (FAO, 1999; Moore, 1982; Webster, 2002; Pender, 1996; Russel; 1985). According to Moore, the eggs of fish not exposed to high salinity water do not develop fully, however, Pender and Griffen (1996) concluded that there are populations that spend their entire life cycles in freshwater, estuarine, or saltwater environments, so there may be exceptions to the requirement for high salinities.

There is one spawning season per year towards the end of the dry season and the beginning of the rainy season in the period from October to February (Moore, 1982). Females carry from 2.3 to 32.2 million eggs and can either shed them all at once or as little as 10% at a time (Moore, 1982). Because Lates calcarifer is a broadcast breeder, it can be inferred that there is little interaction between males and females. However, barramundi tend to spawn around the full moon, when tides will carry the eggs back into estuaries (Luna, 2008).

Lates calcarifer is serially hermaphroditic with males reaching maturity at 37 to 72 cm and changing into females starting at 73 cm, at around five years, three to five years, or six to eight years depending on the source (Moore, 1979, FAO, 1999; Guiguen, 1993). According to Guiguen (1993) males mature at three to five years, but this study was conducted in cage farmed fish, which may have different maturation times than wild fish. Some male specimens do get larger than 73 cm. The transition from male to female is short, lasting as little as a week, and may not occur in all individuals according to Moore (1979).

Chemical levels in the scales of fish from southern Papua New Guinea have indicated that adult barramundi do not always migrate to breeding grounds to spawn, with a lifetime non-participation rate of as much as 50% (Milton, 2005).

Breeding interval: Breeding occurs once yearly in barramundi

Breeding season: Breeding generally occurs from October to February.

Range number of offspring: 2,300,000 to 32,200,000.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 2 to 8 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 3 to 5 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; sequential hermaphrodite (Protandrous ); sexual ; fertilization (External ); broadcast (group) spawning; oviparous

Lates calcarifer is a nonguarding species; there is no parental involvement in the development of fry and juvenile fish (Luna, 2008).

Parental Investment: no parental involvement; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Female)

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Fulton-Howard, B. 2008. "Lates calcarifer" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lates_calcarifer.html

- author

- Brian Fulton-Howard, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Kevin Omland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- editor

- Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web

Benefits

provided by FAO species catalogs

Caught maintly with bottom trawls, handlines, seines, gillnets, and traps. Reaches 1500-3000 g in one year in ponds under optimum conditions. Sold fresh and frozen (marketed mostly fresh); consumed steamed, pan-fried, broiled and baked.

Diagnostic Description

provided by FAO species catalogs

Body elongate, compressed, with a deep caudal peduncle. Head pointed, with concave dorsal profile becoming convex in front of dorsal fin. Mouth large, slightly oblique, upper jaw reaching to behind eye; teeth villiform, no canines present. Lower edge of pre-operculum with a strong spine; operculum with a small spine and with a serrated flap above origin of lateral line. Lower first gill arch with 16 to 17 gillrakers. Scales large, ctenoid. Dorsal fin with 7 to 9 spines and 10 to 11 soft rays; a very deep notch almost dividing spiny from soft part of fin; pectoral fin short and rounded, several short, strong serrations above its base; dorsal and anal fins both have scaly sheaths. Anal fin rounded, with 3 spines and 7 to 8 short rays. Caudal fin rounded. Colour in two phases, either olive brown above with silver sides and belly (usually juveniles) or green/blue above and silver below. No spots or bars present on fins or body.

- Rainboth, W.L. - 1996 FAO species identification field guide for fishery purposes. Fishes of the Cambodian Mekong. Rome, FAO. 1996.: 265 pp.

- Sukhavisidh, P. - 1974Centropomidae. In: W. Fischer & P.J.P. Whitehead. FAO species identification sheets for fishery purposes. Eastern Indian Ocean (fishing area 57) and Western Central Pacific (fishing area 71). Vol. I, Rome FAO, pag var.

Distribution

provided by FAO species catalogs

East Indian Ocean and Western central Pacific. Japanese Sea, Torres Strait or the coast of New Guinea and Darwin, Northern Territory, Queensland (Australia). Also, westward to East Africa.

Size

provided by FAO species catalogs

To 200 cm; common between 25 and 100 cm.

Brief Summary

provided by FAO species catalogs

A diadromous fish, inhabiting rivers before returning to the estuaries to spawn.Found in coastal waters, estuaries and lagoons,in clear to turbid water.Usually occurs at a temperature range of 26-29º C and between 10-40 m. Feeds on fishes and crustaceans.

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Erilepturus Disease. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Columnaris Disease (m.). Bacterial diseases

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Lecithochirium Disease 2. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Pseudometadena Infestation. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Pseudometadena Disease. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Diplectanum Disease. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Rhapidascaris Disease (larvae). Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Epitheliocystis. Bacterial diseases

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Trichodinosis. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Lymphocystis Disease. Viral diseases

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Pterobothrium Infestation 2. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Bucephalus Disease. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Psilostomum Disease. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Dasyrhynchus Infestation 1. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Gymnorhynchus Infestation. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Serrasentis Infestation. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Vibriosis Disease. Bacterial diseases

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Vibriosis Disease (general). Bacterial diseases

Life Cycle

provided by Fishbase

Breed in estuaries throughout the Indo-Pacific. Maturing male barramundi migrate downstream from freshwater habitats at the start of the wet (monsoon) season to spawn with resident females in estuaries (Ref. 27132) and on tidal flats outside the mouths of rivers (Ref. 6390).Barramundi spawn on the full moon and new moon, primarily at the beginning of an incoming tide which carries the eggs into the estuary (Ref. 28135).Barramundi are broadcast spawners that aggregate to spawn (Ref. 6390). Spawning aggregations occur in or around the mouths of rivers (Ref. 28132). While adults and juveniles are capable of living in fresh water, brackish waters are required for embryonic development (Ref. 6136). Female barramundi are capable of producing large numbers of eggs, with estimates as high as 2.3 million eggs per kg of body weight (Ref. 28134).Barramundi are protandrous hermaphrodites, i.e., they undergo sex reversion during their life cycle. Females are generally absent in the smaller length classes, but dominate larger length classes. Most barramundi mature first as males and function as males for one or more spawning seasons before undergoing sex inversion. A few females will develop directly from immature fish (Ref. 28132). Similarly, some males may never undergo sex inversion (Ref. 28132). Also Ref. 103751.

Migration

provided by Fishbase

Catadromous. Migrating from freshwater to the sea to spawn, e.g., European eels. Subdivision of diadromous. Migrations should be cyclical and predictable and cover more than 100 km.

Morphology

provided by Fishbase

Dorsal spines (total): 7 - 9; Dorsal soft rays (total): 10 - 11; Analspines: 3; Analsoft rays: 7 - 8

- Recorder

- Estelita Emily Capuli

Trophic Strategy

provided by Fishbase

Inhabits coral reefs (Ref. 58534). Recorded as having been or being farmed in rice fields (Ref. 119549). Under hatchery conditions, larvae grow to juveniles in 26 days (Ref. 28133). The postlarvae (and possibly larvae) move from spawning areas to brackish water seasonal habitat (Ref. 28131). Larval barramundi occupy these habitats as well as main channels of streams (Ref. 6390). Juveniles live in freshwater lagoons, swamps and creeks (Ref. 28131). As these temporary habitats dry up, the juveniles move into the main stream and many migrate upstream to permanent freshwater habitats (Ref. 6390). Feed on fishes and crustaceans. They reach 1500-3000 g in one year in ponds under optimum conditions (Ref. 11046, 44894). Juveniles also eat insects (Ref. 44894).

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Iridovirosis. Viral diseases

Diagnostic Description

provided by Fishbase

Body elongate; mouth large, slightly oblique, upper jaw extending behind the eye. Lower edge of preopercle serrated, with strong spine at its angle; opercle with a small spine and with a serrated flap above the origin of the lateral line. Caudal fin rounded.

- Recorder

- Estelita Emily Capuli

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Capsalid Monogenean Infection 1. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Glugeosis Disease. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Flexibacter maritimus Infection. Bacterial diseases

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Rhipidocotyle Infestation 7 (Rhipidocotyle sp.). Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Cymothoa Infection. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Cardicola Infection. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Ectenurus Infection 2 (Ectenurus sp.). Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Lecithochirum Infestation 3. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Aegathoa Infestation (Aegathoa sp.). Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Cycloplectanum Infection 2. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Baldness disease in Snapper. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Transversotrema Infestation. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Callitetrarhynchus Disease. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Caligus Infestation 1. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Fish louse Infestation 1. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Anisakis Disease (juvenile). Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

White spot Disease. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Pseudorhabdosynochus Infestation 3. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Lernanthropus Infestation 4. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Pseudorhabdosynochus Infestation 2. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Diseases and Parasites

provided by Fishbase

Cycloplectanum Infection 1. Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Biology

provided by Fishbase

Found in coastal waters, estuaries and lagoons, in clear to turbid water (Ref. 5259, 44894). A diadromous fish, inhabiting rivers before returning to the estuaries to spawn. A protandrous hermaphrodite (Ref. 32209). Larvae and young juveniles live in brackish temporary swamps associated with estuaries, and older juveniles inhabit the upper reaches of rivers (Ref. 6390, 44894). Have preference for cover on undercut banks, submerged logs and overhanging vegetation (Ref. 44894). Feed on fishes and crustaceans. They reach 1500-3000 g in one year in ponds under optimum conditions (Ref. 11046, 44894). Juveniles also eat insects (Ref. 44894). Sold fresh and frozen; consumed steamed, pan-fried, broiled and baked (Ref. 9987). A very popular and sought-after fish of very considerable economic importance (Ref. 9799). Presently used for aquaculture in Thailand, Indonesia and Australia (Ref. 9799). Australia's most important commercial fish and one of the most popular angling species (Ref. 44894).

Importance

provided by Fishbase

fisheries: highly commercial; aquaculture: commercial; gamefish: yes; aquarium: public aquariums; price category: very high; price reliability: reliable: based on ex-vessel price for this species

分布

provided by The Fish Database of Taiwan

主要分布於印度-西太平洋沿岸之半淡鹹水域,西起阿拉伯灣,北至日本,南至澳洲北部。臺灣西部及南部有分布。

利用

provided by The Fish Database of Taiwan

可以流刺網、一支釣與延繩釣等漁法捕獲。為東南亞地區之重要養殖魚種,臺灣沿海也有產,但以南部養殖較多。可清蒸、紅燒或煮湯食用。

描述

provided by The Fish Database of Taiwan

體長而側扁,腹緣平直。頭尖,頭背側、眼睛上方有一明顯凹槽。眼略小。前後鼻孔相近。吻短而略尖。口大,下頜略突出;上頜後端達眼後下方。眶前骨與前鰓蓋骨均無鋸齒之雙重邊緣,前鰓蓋骨下緣3-4硬棘。上、下頜、鋤骨、腭骨及翼骨上均有絨毛狀齒帶,舌上無齒。被細小櫛鱗;側線鱗數60-63。背鰭單一,具深缺刻,鰭條數為VII-VIII+I,

11;臀鰭鰭條數為III+8;胸鰭短;尾鰭圓形。成魚體呈銀白色,體背側灰褐至藍灰色,各鰭灰黑或淡色;幼魚褐色至灰褐色,頭部具3條白紋,體側散布白色斑紋,眼褐色至金黃色,隨成長而略具淡紅色虹彩。

棲地

provided by The Fish Database of Taiwan

為熱帶及亞熱帶沿岸海域魚類,棲息於岩岸礁石與泥沙交匯處,而常活動於半淡鹹水水域,亦會溯入淡水河川。屬廣鹽性魚類且不耐低溫。

Barramundi

provided by wikipedia EN

The barramundi (Lates calcarifer), Asian sea bass, or giant sea perch, is a species of catadromous fish in the family Latidae of the order Perciformes. The species is widely distributed in the Indo-West Pacific, spanning the waters of the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania.

Origin of name

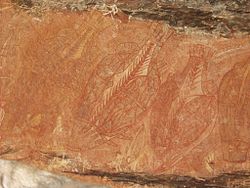

Indigenous Australian rock art depicting barramundi fish

Barramundi is a loanword from an Australian Aboriginal language of the Rockhampton area in Queensland[3] meaning "large-scaled river fish".[4] Originally, the name barramundi referred to Scleropages leichardti and Scleropages jardinii.[5]

However, the name was appropriated for marketing reasons during the 1980s, a decision that significantly raised the profile of this fish.[5] L. calcarifer is broadly referred to as Asian seabass by the international scientific community, but is sometimes known as Australian seabass or giant sea perch.[6][7][8]

Description

This species has an elongated body form with a large, slightly oblique mouth and an upper jaw extending behind the eye. The lower edge of the preoperculum is serrated with a strong spine at its angle; the operculum has a small spine and a serrated flap above the origin of the lateral line. Its scales are ctenoid. In cross section, the fish is compressed and the dorsal head profile clearly concave. The single dorsal and ventral fins have spines and soft rays; the paired pectoral and pelvic fins have soft rays only; and the caudal fin has soft rays and is truncated and rounded. Barramundi are salt and freshwater sportfish, targeted by many. They have large, silver scales, which may become darker or lighter, depending on their environments. Their bodies can reach up to 1.8 m (5.9 ft) long, though evidence of them being caught at this size is scarce. The maximum weight is about 60 kg (130 lb). The average length is about 0.6–1.2 m (2.0–3.9 ft). Its genome size is about 700 Mb, which was sequenced and published in Animal Genetics (2015, in press) by James Cook University.

Barramundi are demersal, inhabiting coastal waters, estuaries, lagoons, and rivers; they are found in clear to turbid water, usually within a temperature range of 26−30 °C. This species does not undertake extensive migrations within or between river systems, which has presumably influenced establishment of genetically distinct stocks in Northern Australia.

Life cycle

Barramundi piebald colour morph

The barramundi feeds on crustaceans, molluscs, and smaller fish (including its own species); juveniles feed on zooplankton. The barramundi is euryhaline, but stenothermal. It inhabits rivers and descends to estuaries and tidal flats to spawn. In areas remote from fresh water, purely marine populations may become established.

At the start of the monsoon, males migrate downriver to meet females, which lay very large numbers of eggs (several millions each). The adults do not guard the eggs or the fry, which require brackish water to develop. The species is sequentially hermaphroditic, with most individuals maturing as males and becoming female after at least one spawning season; most of the larger specimens are therefore female. Fish held in captivity sometimes demonstrate features atypical of fish in the wild; they change sex at a smaller size, exhibit a higher proportion of protogyny and some males do not undergo sexual inversion.[9]

Recreational fishing

Prized by anglers and sport-fishing enthusiasts for their good fighting ability,[10] barramundi are reputed to be good at avoiding fixed nets and are best caught on lines and with fishing lures. In Australia, the barramundi is used to stock freshwater reservoirs for recreational fishing.

These "impoundment barramundi", as they are known by anglers, have grown in popularity as a "catch and release" fish. Popular stocked barramundi impoundments include Lake Tinaroo near Cairns in the Atherton Tablelands, Lake Proserpine west of Proserpine, Queensland, Teemburra Dam near Mackay, Lake Moondarra near Mount Isa, Lake Awoonga near Gladstone, and Lake Monduran south of Lake Awoonga.

Commercial fishing and aquaculture

The fish is of commercial importance; it is fished internationally and raised in aquaculture in Australia,[10] Singapore, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Israel, Thailand, the United States, Poland, and the United Kingdom. A Singapore investment firm has invested in an upcoming barramundi fish farm in Brunei. The Australian barramundi industry is relatively established, with an annual production of more than 4,000 tons. In the broader Southeast Asian region, production is estimated to exceed 30,000 tons. By contrast, the US industry produces about 800 tons a year from a single facility, Australis Aquaculture, LLC. In 2011, VeroBlue Farms in Iowa started and aims to produce 500 tons annually.[11] Barramundi under culture commonly grow from a hatchery juvenile, between 50 and 100 mm in length, to a table size of 400-600 g within 12 months and to 3.0 kg within 18–24 months.[9]

Diseases

Though Asian sea bass are a hardy fish, they are vulnerable to bacterial infections like photobacteriosis.[12]

Aquarium use

Juveniles are a popular aquarium fish,[10] and can be very entertaining, especially at feeding time. However, they grow quickly, so they are recommended to be kept in setups of 500 L or larger. In aquaria, they become quite tame and can be hand-fed; they are not aggressive, but their feeding reflex is violent and sudden, so they cannot be kept with any tank mates small enough to be swallowed.

As food

Barramundi have a mild flavour and a white, flaky flesh, with varying amount of body fat.

Barramundi are a favourite food of the region's apex predator, saltwater crocodiles, which have been known to take them from unwary fishermen.[13]

Australian cuisine

In Australia, such is the demand for the fish that a substantial amount of barramundi consumed there is actually imported. This has placed economic pressure on Australian producers, both fishers and farmers, whose costs are greater due to remoteness of many of the farming and fishing sites, as well as stringent environmental and food safety standards placed on them by government. While country-of-origin labelling has given consumers greater certainty over the origins of their barramundi at the retail level, no requirement exists for the food service and restaurant trades to label the origins of their barramundi.

Bengali cuisine

Locally caught bhetki (barramundi) is a popular fish among Bengali people, mainly served in festivities such as marriages and other important social events. It is cooked as bhetki machher paturi, bhetki machher kalia, or coated in suji (semolina) and pan fried. It is very popular among people who are usually skeptical about eating fish with a lot of bones. Bhetki fillets have no bones in them. In Bengali cuisine, therefore, fried bhetki fillets are popular and considered to be of good quality. The dish is commonly called "fish fry".

Goan cuisine

Locally caught chonak (barramundi) is a favourite food, prepared with either recheado (a Goan red masala) or coated with rava (sooji, semolina)[14] and pan fried. The fish is generally filleted on the diagonal. It is eaten as a snack or as an accompaniment to drinks or the main course. It is one of the more expensive fish available.

Thai cuisine

Barramundi from local fish farms are known as pla kapong (Thai: ปลากะพง) in Thailand.[15] Since its introduction, it has become one of the most popular fish in Thai cuisine. It is often eaten steamed with lime and garlic, as well as deep-fried or stir-fried with lemongrass, among a variety of many other ways. Pla kapong can be seen in aquaria in many restaurants in Thailand, where sometimes this fish is wrongly labeled as "snapper" or "sea bass" on menus.[16] Traditionally, Lutjanidae snappers were known as pla kapong before the introduction of barramundi in Thai aquaculture, but presently, snapper is rarely served in restaurants in the main cities and in interior Thailand.

United States

In the US, barramundi is growing in popularity. Monterey Bay Aquarium has deemed US and Vietnam-raised barramundi as "Best Choice" under the Seafood Watch sustainability program.[17]

See also

References

-

^ Pal, M.; Morgan, D.L. (2019). "Lates calcarifer". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T166627A1139469. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T166627A1139469.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

-

^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2019). "Lates calcarifer" in FishBase. December 2019 version.

-

^ Yokose, Hiroyuki. "Aboriginal Words in Australian English" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2006.

-

^ Frumkin, Paul (2003). "Barramundi approval rating rise". Food & Beverage Industry. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

-

^ a b "Australia's Arrow Fish, Saratoga (The True Barramundi)". Archived from the original on 29 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

-

^ Banerjee, Debashis; Hamod, Mohammed A.; Suresh, Thangavel; Karunasagar, Indrani (1 December 2014). "Isolation and characterization of a nodavirus associated with mass mortality in Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) from the west coast of India". VirusDisease. 25 (4): 425–429. doi:10.1007/s13337-014-0226-8. ISSN 2347-3517. PMC 4262316. PMID 25674617.

-

^ Pierce, Charles (26 November 2006). "The Next Big Fish - The Boston Globe". Boston Globe Magazine. Boston Globe. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

-

^ "Common Names Summary - Lates calcarifer". www.fishbase.se.

-

^ a b "FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PAPER No. 127" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

-

^ a b c Gomon, Martin. "Barramundi, Lates calcarifer". Fishes of Australia. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

-

^ Oatman, Maddie (January 2017). "A Fish Out of Water". Mother Jones. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

-

^ Trung Hieu Pham; Shreesha Rao; Ta-Chih Cheng; Pei-Chi Wang; Shih-Chu Chen (2021). "The moonlighting protein fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase as a potential vaccine candidate against Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida in Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer)". Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 124 (104187): 104187. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2021.104187. ISSN 0145-305X. PMID 34186149.

-

^ Garrick, Matt (25 March 2019). "Crocodile steals massive barramundi from NT fisherman at the last possible second". ABC News. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

-

^ Oulton, R (2007) [First published 2005]. "Sooji". Cooks Info. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

-

^ Fishing in Thailand Archived 2009-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

-

^ Ruen Urai, Thai cuisine Archived 2011-07-15 at the Wayback Machine

-

^ "Giant perch". www.seafoodwatch.org. Seafood Watch. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Barramundi: Brief Summary

provided by wikipedia EN

The barramundi (Lates calcarifer), Asian sea bass, or giant sea perch, is a species of catadromous fish in the family Latidae of the order Perciformes. The species is widely distributed in the Indo-West Pacific, spanning the waters of the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors