en

names in breadcrumbs

The Sundaland clouded leopard is a large predator and has very few predators of its own. They are illegally hunted by humans for their coats as well certain body parts that are used in traditional medicine. On Sumatra, tigers are thought to be important predators, however, this has not been confirmed. During the day, Sundaland clouded leopards remain in the canopy more than during the night, presumably to avoid tigers. They are very well camouflaged, which likely helps reduce risk of predation.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

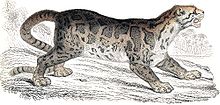

Sundaland clouded leopards are medium-sized and have large spots along its entire body which resemble clouds. Their spots are darker and larger than the mainland clouded leopard, and the coat is darker than that of their mainland counterpart. The spots on their coat are outlined in black and the inside is darker than their primary coat color. They have two distinct black bars on the back of their necks, as well as large black ovals on the venter. The exceptionally long tail, which helps with balance while traveling in the canopy, is covered in thick fur and has a number of dark black rings along its length. They have short legs and broad paws, which make it exceptional at climbing trees, as well as moving silently through dense forests. The hind feet have very flexible joints, which allow them to descend from the canopy head first. Their flexible joints also enables them to hang from a branch using only their hind feet while using their forefeet to capture prey. Sundaland clouded leopards have exceptionally large canine teeth, which can be up to 5 cm long. In porportion to their body size, they have the largest canines of any felid. The morphology of their jaws and teeth are similar to those of extinct saber-toothed cats. Head and body length ranges from 60 to 110cm, tail length ranges from 55 to 91cm long and weight ranges from 15 to 30 kg. Males are generally larger than females.

Range mass: 15 to 30 kg.

Range length: 115 to 201 cm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male larger

There is no information available regarding the average lifespan of Neofelis diardi.

Sundaland clouded leopards are primarily forest-dwellers, however, they have been observed in other habitats as well. They are most abundant in hilly areas on the island of Sumatra, and have been observed in the lowland rain forests of Borneo as well, below 1500 m. Evidence suggests that they occupy low-elevation habitats due to the absence of large predators such as tigers. They are often sighted on the periphery of logged forests and close to human civilizations, likely due to extensive habitat loss occurring throughout its geographic range. Sundaland clouded leopards are about six times more abundant on Borneo than on Sumatra. They are highly arboreal and are particularly fond of trees overhanging ridges or cliffs. In areas containing tigers, a known predator of Sundaland clouded leopards, they rarely descend to the ground and are thought to travel through the canopy. They appear to be more arboreal on the island of Sumatra than in other areas of their geographic range, possibly due to sympatry with tigers. Despite their highly arboreal nature, they occasionally travel alongside logging roads as well.

Range elevation: < 1500 (low) m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: forest

Sundaland clouded leopards is commonly referred to as the Bornean clouded leopard, Sunda clouded leopard, Sunda Islands clouded leopard, and Enkuli clouded leopard. They were recently declared a new species because of significant differences from mainland clouded leopards. It was determined that they had 41 fixed mitochondrial nucleotide differences and non-overlapping allele sizes in 8 of 18 microsatellite loci shared between the two species. This is equivalent to the number of differences between lions and tigers. Scientists have also declared two sub-species of Sundaland clouded leopards. Neofelis diardi borneensis is found exclusively on Bornea, whereas Neofelis diardi diardi is found exclusively on Sumatra.

There is little information available regarding communication and perception in Sundaland clouded leopards. With the exception of breeding season and when females are with cubs, they are highly solitary. They are territorial and appear to use logging roads as boundaries, which are openly and frequently crossed. They are thought to demarcate territorial bounderies with urine. There is no information available regarding intraspecific communication with mates and young.

Communication Channels: chemical

Other Communication Modes: scent marks

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Sundaland clouded leopards are classified as vulnerable on the IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species. Major threats include rapid and extensive deforestation for agricultural expansion (e.g., oil palm) and settlements. Rapid deforestation to establish oil-palm plantations is a major road block to the longterm persistence of this species. Deforestation laws are rarely enforced and even wildlife sanctuaries and national forests have been somewhat deforested since 1970. Deforestation not only decreases the amount of available habitat for this species, but reduces available habitat for potential prey as well. Additional threats include illegal hunting and accidental trapping. Two subspecies have been recognized, Neofelis diardi borneensis and Neofelis diardi diardi, both of which are classified as endangered on the IUCN's Red List of Threatened Species. Sundaland clouded leopards occur in a number of protected areas throughout its geographic range and is listed under Appendix 1 by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).

CITES: appendix i

There is no information available regarding the development of Neofelis diardi.

Sundaland clouded leopards occasionally prey on livestock from villages surrounded by vast forest in Sumatra and Borneo. There are no records of Sundaland clouded leopards attacking humans.

Sundaland clouded leopards are illegally hunted for their coats and various body parts are used in traditional medicine. Tissue samples from carcasses have been used in phylogenetic research, which has helped establish the relationship of this species to other felids.

Positive Impacts: body parts are source of valuable material; source of medicine or drug

There is no information available regarding the potential impact that Neofelis diardi has on its local environment.

Sundaland clouded leopards are carnivorous and feed on a wide variety terrestrial and arboreal prey. They regularly feed on sambar deer, barking deer, mouse deer, bearded pig, Palm civet, gray leaf monkey, fish, birds and porcupines. They have been observed preying upon proboscis monkeys as well; specifically, they target infant proboscis monkeys or juvenile females. They are ambush predators and attack prey from the canopy. They have been known to remove the limbs of their prey and bring them into trees for protection against leeches and to relax while feeding.

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; fish

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats terrestrial vertebrates)

Sundaland clouded leopards occur on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra in the Malay Archipelago. It is currently unknown if Sundaland clouded leopards are on Batu, a smaller island close to Sumatra. Fossils of clouded leopards have been found on the island of Java. Sundaland clouded leopards are believed to have diverged from mainland clouded leopards approximately 1.5 million years ago due to geographic barriers. The presence of Sundaland clouded leopards on the Malay Peninsula has not been confirmed.

Biogeographic Regions: oriental (Native )

Neofelis diardi is thought to be seasonally monogamous. There is no further information available regarding the mating system of this species.

Mating System: monogamous

There is little information available regarding breeding behavior in Sundaland clouded leopards, and all available information was gathered by observing captive individuals. Captive breeding has been mostly unsuccessful due to aggression between mates, which occasionally results in the death of the female. If introduced at a young age, aggression is not as pronounced and has allowed for more successful breeding. They are believed to exhibit similar breeding behaviors as mainland clouded leopards. Most Sundaland clouded leopards become sexually mature around 2 years of age. Mating can occur during any month of the year, but peaks between December and March. Gestation ranges from 85 to 95 days and results in 1 to 5 cubs, with an average of 2 cubs per litter. Cubs are usually independent once they reach 10 months old and become reproductively mature by 2 years of age. The females are able to produce a litter every year.

Breeding interval: Sundaland clouded leopards breed once yearly

Breeding season: Breeding activity in Sundaland clouded leopards occurs year-round but peaks from December through March.

Range number of offspring: 1 to 5.

Average number of offspring: 2.

Range gestation period: 85 to 95 days.

Average time to independence: 10 months.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 2 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 2 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (Internal ); viviparous

There is little information available regarding parental care in Sundaland clouded leopards. Mothers nurse cubs until about 10 months of age, at which time they become independent.

Parental Investment: precocial ; female parental care ; pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Female)

The Sunda clouded leopard (Neofelis diardi) is a medium-sized wild cat native to Borneo and Sumatra. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 2015, as the total effective population probably consists of fewer than 10,000 mature individuals, with a decreasing population trend. On both Sunda Islands, it is threatened by deforestation.[1] It was classified as a separate species, distinct from the clouded leopard in mainland Southeast Asia based on a study in 2006.[2] Its fur is darker with a smaller cloud pattern.[3][4]

This cat is also known as the Sundaland clouded leopard, Enkuli clouded leopard,[1] Diard's clouded leopard,[5] and Diard's cat.[6]

The Sunda clouded leopard is overall grayish yellow or gray hue. It has a double midline on the back and is marked with small irregular cloud-like patterns on shoulders. These cloud markings have frequent spots inside and form two or more rows that are arranged vertically from the back on the flanks.[3] It can purr as its hyoid bone is ossified. Its pupils contract to vertical slits.[7]

It has a stocky build and weighs around 12 to 26 kg (26 to 57 lb). Its canine teeth are 2 in (5.1 cm) long, which, in proportion to the skull length, are longer than those of any other living cat. Its tail can grow to be as long as its body, aiding balance.

The Sunda clouded leopard is restricted to the islands of Borneo and Sumatra. In Borneo, it occurs in lowland rainforest, and at lower density in logged forest below 1,500 m (4,900 ft). In Sumatra, it appears to be more abundant in hilly, montane areas. It is unknown if it still occurs on the Batu Islands close to Sumatra.[1]

Between March and August 2005, tracks of clouded leopards were recorded during field research in the Tabin Wildlife Reserve in Sabah. The population size in the 56 km2 (22 sq mi) research area was estimated to be five individuals, based on a capture-recapture analysis of four confirmed animals differentiated by their tracks. The density was estimated at eight to 17 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi). The population in Sabah is roughly estimated at 1,500–3,200 individuals, with only 275–585 of them living in totally protected reserves that are large enough to hold a long-term viable population of more than 50 individuals.[8] Density outside protected areas in Sabah is probably much lower, estimated at one individual per 100 km2 (39 sq mi).[9]

In Sumatra, it was recorded in Kerinci Seblat, Gunung Leuser and Bukit Barisan Selatan National Parks.[10][11][12] It occurs most probably in much lower densities than on Borneo. One explanation for this lower density of about 1.29 individuals per 100 km2 (39 sq mi) might be that on Sumatra it is sympatric with the Sumatran tiger, whereas on Borneo it is the largest carnivore.[13]

Clouded leopard fossils were excavated on Java, where it perhaps became extinct in the Holocene.[14]

The habits of the Sunda clouded leopard are largely unknown because of the animal's secretive nature. It is assumed that it is generally solitary. It hunts mainly on the ground and uses its climbing skills to hide from dangers.

Felis diardi was the scientific name proposed by Georges Cuvier in 1823 in honour of Pierre-Médard Diard, who sent a skin and a drawing from Java to National Museum of Natural History, France.[15] It was subordinated as a clouded leopard subspecies by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1917.[16]

Results of molecular genetic analysis of hair samples from mainland and Sunda clouded leopards showed differences in mtDNA, nuclear DNA sequences, and microsatellite and cytogenetic variation. This indicates that they diverged between 2 and 0.9 million years ago; their last common ancestor probably crossed a now submerged land bridge to reach Borneo and Sumatra.[2] Results of a morphometric analysis of the pelages of 57 clouded leopards sampled throughout the genus' wide geographical range indicated that the two morphological groups differ primarily in the size of their cloud markings. The genus Neofelis was therefore reclassified as comprising two distinct species, N. nebulosa on the mainland and N. diardi in Sumatra and Borneo.[2][3]

Molecular, craniomandibular, and dental analysis indicates the Sunda clouded leopard has two distinct subspecies with separate evolutionary histories:[17]

Both populations are estimated to have diverged during the Middle to Late Pleistocene. This split corresponds roughly with the catastrophic super-eruption of the Toba Volcano in Sumatra 69,000–77,000 years ago. A probable scenario is that Sunda clouded leopards from Borneo recolonized Sumatra during periods of low sea levels in the Pleistocene, and were later separated from their source population by rising sea levels.[17]

Sunda clouded leopards being strongly arboreal are forest-dependent, and are increasingly threatened by habitat destruction following deforestation in Indonesia as well as in Malaysia.[1]

Since the early 1970s, much of the forest cover has been cleared in southern Sumatra, in particular lowland tropical evergreen forest. Fragmentation of forest stands and agricultural encroachments have rendered wildlife particularly vulnerable to human pressure.[18] Borneo has one of the world's highest deforestation rates. While in the mid-1980s forests still covered nearly three quarters of the island, by 2005 only 52% of Borneo was still forested. Both forests and land make way for human settlement. Illegal trade in wildlife is a widely spread practice.[19]

The population status of Sunda clouded leopards in Sumatra and Borneo has been estimated to decrease due to forest loss, forest conversion, illegal logging, encroachment, and possibly hunting. In Borneo, forest fires pose an additional threat, particularly in Kaltimantan and in the Sebangau National Park.[20]

There have been reports of poaching of Sunda clouded leopards in Brunei's Belait District where locals are selling their pelts at a lucrative price.[21]

In Indonesia, the Sunda clouded leopard is threatened by illegal hunting and trade. Between 2011 and 2019, body parts of 32 individuals were seized including 17 live individuals, six skins, several canines and claws. One live individual seized in Jakarta had been ordered by a Kuwaiti buyer.[22]

Neofelis diardi is listed on CITES Appendix I, and is fully protected in Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei. Sunda clouded leopards occur in most protected areas along the Sumatran mountain spine and in most protected areas on Borneo.[1]

Since November 2006, the Bornean Wild Cat and Clouded Leopard Project based in the Danum Valley Conservation Area and the Tabin Wildlife Reserve aims to study the behaviour and ecology of the five species of Bornean wild cat — bay cat, flat-headed cat, marbled cat, leopard cat, and Sunda clouded leopard — and their prey, with a focus on the clouded leopard; investigate the effects of habitat alteration; increase awareness of the Bornean wild cats and their conservation needs, using the clouded leopard as a flagship species; and investigate threats to the Bornean wild cats from hunting and trade in Sabah.[23]

The Sunda clouded leopard is one of the focal cats of the project Conservation of Carnivores in Sabah based in northeastern Borneo since July 2008. The project team evaluates the consequences of different forms of forest exploitation for the abundance and density of felids in three commercially used forest reserves. They intend to assess the conservation needs of these felids and develop species specific conservation action plans together with other researchers and all local stakeholders.[24]

The scientific name of the genus Neofelis is a composite of the Greek word νεο- meaning "new, fresh, strange", and the Latin word feles meaning "cat", so it literally means "new cat."[25][26]

The Indonesian name for the clouded leopard rimau-dahan means "tree tiger" or "branch tiger".[27] In Sarawak, it is known as entulu.[28]

The Sunda clouded leopard (Neofelis diardi) is a medium-sized wild cat native to Borneo and Sumatra. It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 2015, as the total effective population probably consists of fewer than 10,000 mature individuals, with a decreasing population trend. On both Sunda Islands, it is threatened by deforestation. It was classified as a separate species, distinct from the clouded leopard in mainland Southeast Asia based on a study in 2006. Its fur is darker with a smaller cloud pattern.

This cat is also known as the Sundaland clouded leopard, Enkuli clouded leopard, Diard's clouded leopard, and Diard's cat.