en

names in breadcrumbs

The Chinook Salmon has 17 distinct Evolutionarily Significant Units, (ESU) in the US only, two of which are endangered and seven of which are threatened.

ENDANGERED:

Sacramento River Winter Run,

Upper Columbia River Spring Run

THREATENED:

Snake River Fall Run,

Snake River Spring/Summer Run,

Central Valley Spring Run,

California Coastal,

Puget Sound,

Lower Columbia,

Upper Willamette,

CANDIDATE:

Central Valley Fall Run

NOT WARRANTED:

S. Oregon/N. California Coastal,

Upper Klamath Trinity,

Oregon Coastal,

Washington Coastal,

Mid Columbia Spring Run,

Upper Columbia Summer/Fall Run,

Deschules Summer/Fall Run

Many agencies have been set up to protect this species, including the Pacific Fisheries Management Council, the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council, and the National Marine Fisheries Service. The federal Magnuson-Stevens Act was made to protect the Essential Fish Habitat, the waters and substrates necessary to fish for spawning, breeding, feeding and growing to maturity. The Sustainable Fisheries Act has amended the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

The main causes for the declining fish populations are overfishing, damming and diverting water, habitat destruction, and introducing hatchery populations. Overfishing has decreased population sizes enough that all other causes, along with natural predation, can have extreme effects, and population sizes decrease rapidly. Damming causes decline because it blocks adults from returning to their birthplace and because smolts often get sucked into the turbines of hydroelectric dams and are killed. Diverting water away from salmon streams causes water temperature to rise, reducing the oxygen carrying capacity of the water. Temperatures could also become fatally high in the summer. Reduced water levels could expose eggs in the winter, or flows could be too low to carry smolts out to sea. Habitat destruction, including logging, clearing rivers, pollution, and wetlands destruction, take away shade and necessary protection for juveniles. After logging has changed runoff patterns, streams may contain too much silt and become uninhabitable. Pollution can cause many physiological problems, including increased susceptibiity to pathogens. Introducing hatchery populations adds to the decline because the introduced populations interbreed with the native populations and can reduce resistence to disease (Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, 1996; National Wildlife Federation, 2002; NOAA, 2001; University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, 2002; Arkoosh and Collier, 2002).

US Federal List: endangered

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

For young Chinook Salmon, predation is very high. Many species eat the fry and smolts, including striped bass, American shad, sculpins and sea gulls. Reaching adulthood does not release them from predation, however, as they are still prey to many animals when they return to spawn. Most common are bears, orcas, sea lions, seals, otters, eagles, terns and cormorants. People have made predation worse by concentrating adult salmon at dams and weirs (Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, 1996; National Wildlife Federation, 2002; NOAA, 2001; University of California at Berkeley).

Known Predators:

The Chinook Salmon is the largest of all Pacific salmon species, often larger than 100 lbs and longer than 5 ft. It is characterized by a deep blue-green back, silvery sides and a white belly with black irregular spots on the back, dorsal fin and both lobes of the tail. It also has a small eye, black gum coloration, a thick caudal peduncle and 13-19 anal rays. For spawning, both males and females develop a reddish hue on the sides, although males may be deeper in color. Males can also be distinguished by a hooked nose and a ridged back. The Chinook fry look very different, with well developed parr marks (vertical bars) on their sides.

Range mass: 61.4 (high) kg.

Average mass: 13.6 kg.

Range length: 147.32 (high) cm.

Average length: 91.44 cm.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: male more colorful; sexes shaped differently

The average age of spawning adults is 4-6 years, however, they can spend up to 8 years in the ocean or return after less than one year. The average age is slightly younger in the south with 2/3/4 year-olds most common; 5/6/7 year-olds are most common in the north. Often, females are older than males at sexual maturity. There is high mortality early because of high natural predation, and those smolts that do not reach a certain size before their first winter at sea will not survive colder temperatures. Human modification of the environment has led to even higher mortality, mainly due to siltation and decreased water flow which have reduced the availability of oxygen to the eggs and fry (Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, 1996; Delaney and ADFG, 1994; Government of Canada, 2002).

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 8 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 3-4 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 9.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 2.5 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 5.0 years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 7.0 years.

The Chinook Salmon is anadromous– born in freshwater, migrating to the ocean, and returning as mature adults to their natal streams to spawn. Freshwater streams, estuaries, and the open ocean are all important habitats. The freshwater streams are relatively deep with course gravel. The water must be cool, under 14 C for maximum survival, and fast flowing. Estuaries provide a transition zone between the freshwater and saltwater and the more vegetation the better because there will be more feeding and hiding opportunities. At sea, Chinook Salmon can either stay close to shore or migrate thousands of miles to deep in the Pacific.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; saltwater or marine ; freshwater

Aquatic Biomes: pelagic ; lakes and ponds; rivers and streams; coastal

Other Habitat Features: estuarine

Chinook Salmon are found natively in the Pacific from Monterey Bay, California to the Chukchi Sea, Alaska in North America and from the Anadyr River, Siberia to Hokkaido, Japan in Asia. It has also been introduced to many places around the world including the Great Lakes and New Zealand.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Introduced , Native ); palearctic (Native ); australian (Introduced ); pacific ocean (Native )

While in freshwater, Chinook Salmon fry and smolts feed on plankton and then terrestrial and aquatic insects, amphipods and crustaceans. After migrating to the ocean, the maturing adults feed on large zooplakton, herring, pilchard, sandlance and other fishes, squid, and crustaceans. Once the adult salmon have re-entered freshwater, they do not feed. In the Great Lakes, Chinook Salmon were introduced to control the invasive alewife population (National Wildlife Federation, 2002; Delaney and ADFG, 1994; Government of Canada, 2002).

Animal Foods: fish; insects; mollusks; aquatic crustaceans; zooplankton

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore , Insectivore , Eats non-insect arthropods, Molluscivore ); planktivore

Spawning Chinook Salmon are the keystone species in many streams because so many other species rely on them for food. In the ocean, they are often one of the top predators. Chinook Salmon are now the top predator in the Great Lakes where they were introduced to control other non-native fish species (University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, 2002).

Ecosystem Impact: keystone species

The Chinook Salmon is very important to commercial, recreational, and subsistence fishermen. It has always been central to the Native American lifestyle on the Pacific coast, and now much of the economy of the Pacific Northwest is based on it. Despite being relatively rare (compared to other Pacific Salmon species) it is the most commercially valuable. It is also now an important big game fish in the Great Lakes and is a big tourist draw in both the Pacific and Great Lakes regions

(Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, 1996; National Wildlife Federation, 2002; Delaney and ADFG, 1994; University of Wisconsin Sea Grant Institute, 2002).

Positive Impacts: food ; ecotourism ; controls pest population

The female digs a nest (called a redd) in the gravel and then deposits her eggs and the male deposits sperm. After 90-150 days (depending on temperature) the eggs hatch, and the alevins (fry with yolksacs attached to the underside) stay in the gravel until the yolksac is used up. The fry then emerge from the gravel in the spring and feed and grow for a few months to two years, depending on the stream system. They then migrate downstream as smolts, following the natural current. The smolts undergo huge physiological changes in their transition from freshwater to salt water. They then spend the next 1-7 years growing and maturing at sea. Growth rates in the ocean are much faster, and perhaps as much as 99% of the somatic growth occurs as sea. Mature adults will then return to their natal streams to spawn. Once the adults have re-entered freshwater, they no longer feed, and they complete sexual maturation during the freshwater migration (Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, 1996; National Wildlife Federation, 2002; NOAA, 2001; Delaney and ADFG, 1994; University of California at Berkeley; Government of Canada, 2002; Ewing and Ewing, 2002; Satterfield and Finney, 2002).

External fertilization in Chinook Salmon requires precise communication in order to ensure proper timing of gamete release. During the courtship, which can last up to several hours, the male vibrates and crosses in front of the female, while the female is preparing for spawning by digging the redd. The female has been shown to selectively choose larger males, who vibrate more. A few seconds before depositing her eggs, the female will shake quickly next to the male, inducing sperm release (Berejikian, Tezak, and LaRae, 2001).

Other Communication Modes: vibrations

Perception Channels: tactile ; chemical

Chinook Salmon population sizes have been shown to fluctuate with long-term climate changes. The most dramatic example of this is the El Nino events, every 3-7 years, which bring warm water into the Pacific and negatively affect Chinook Salmon populations. Longer term changes have involved changes in water currents over time, which have had opposite effects in Alaska and along the coast of California. In Alaska, these changes have caused a change in the mixing layer which has increased the chlorophyll levels in plankton, making the system more productive. This has increased the zooplankton population, which in turn causes an increase in the salmon population size. In California, however, climatic changes have caused the mixing layer to deepen, which has reduced the amount of nutrients available, causing the salmon population to decrease (Taylor and Southards, 1997; Satterfield and Finney, 2002; Botsford and Lawrence, 2002; Dalton, 2001).

The Chinook Salmon have seasonal runs in which all adults return to their natal streams and spawn at approximately the same time of year. Sexual maturity can be anywhere from 2-7 years, so within any given run, size will vary considerably. Salmon are semalparous, and shortly after spawning they die.

After migrating back to the exact place of birth, with very little straying, the adults span in the course gravel of the river. The female first digs a redd in the gravel with an undulating motion of her tail, while the male stands guard. The female then deposits her eggs (3000-14000) in the nest, sometimes in 4-5 different packets within a single redd. The male then deposits his sperm, and both parents guard the redd until they die, sometime within the next 25 days. Spawning is timed so that the fry will emerge in the spring, the time where the stream has the highest productivity.

Many streams have more than one run, with each run going to a slightly different location in the stream. In each location, different environmental factors will affect the timing of the run, all timed so the fry emerge in the spring. For example, in a stream with spring and summer runs, often the spring run will go to higher elevation and with the colder temperature, the eggs will take longer to hatch (Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, 1996; National Wildlife Federation, 2002; Matthews and Waples, 1991; NOAA, 2001; Delaney and ADFG, 1994; Government of Canada, 2002).

Breeding season: Spawning season varies, but the most common runs are in the summer and fall with some streams having runs in the spring and winter as well.

Range number of offspring: 3000 to 14000.

Range gestation period: 90 to 150 days.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 1 to 8 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 0.75 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 1 to 8 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 0.75 years.

Key Reproductive Features: semelparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (External ); oviparous

There is no parental care in Chinook Salmon, as both parents die before the young emerge. However, the decomposing adult carcasses provide necessary nutrients to the eggs and fry.

Parental Investment: no parental involvement

Listen to the podcast, meet the Stream of Dreams team and find audio extras on the Learning + Education section of EOL.

Chinook or King Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) are the largest salmon. They may reach around 150 cm in length and can occasionally exceed 23 kg; other salmon rarely exceed 14 kg. These fish have black spots on the back and on the dorsal, adipose and both lobes of the caudal (tail) fin. The gums are dark at the base of the teeth. At sea, these fish are blue, green, or gray above and silver below. Small males are often dull yellow while large males are often blotchy with dull red on the side. Breeding individuals are dark olive-brown to purple. (Page and Burr 1991)

The Chinook is the least abundant of the Pacific Salmon. It is anadromous (moving from the ocean to freshwater to breed), occurring in the Pacific Ocean and coastal streams. It is found in northeast Asia and, in North America, in Arctic and Pacific drainages from Point Hope, Alaska, to the Ventura River in California, occasionally straying south to San Diego, California. This species is widely stocked outside its range, notably in the Great Lakes. (Page and Burr 1991)

In comparison to other Pacific salmon: Sockeye and Chum Salmon (O. nerka and O. keta) have no large black spots; Coho Salmon (O. kisutch) have no black spots on the lower lobe of the caudal fin and have gums that are light at the base of the teeth; and Pink Salmon (O. gorbuscha) have large oval black spots on the back and caudal fin and do not exceed 76 cm in length. (Page and Burr 1991)

Chinook Salmon spawn once and die. For detailed information on the biology and status of this species, including conservation issues, see this resource from the NOAA Fisheries Office of Protected Resources.

El salmó reial o salmó reial del Pacífic[1] (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) és una espècie de peix de la família dels salmònids i de l'ordre dels salmoniformes.

És depredat per la perca americana, Ptychocheilus oregonensis, el llobarro atlàntic ratllat, Sander vitreus, Megalocottus platycephalus, la truita de Clark, la truita arc de Sant Martí, Salvelinus malma malma, el salmó platejat, la foca comuna i el tauró dormilega del Pacífic.[5]

Viu a zones d'aigües dolces, salobres i marines temperades (72°N-27°N, 136°E-109°W) fins als 375 m de fondària.[6][4]

Es troba des de Point Hope (Alaska)[7][8] fins al riu Ventura (Califòrnia, Estats Units), tot i que, ocasionalment, ha estat vist fins a San Diego (Califòrnia). També és present a Honshu (el Japó),[9] el mar del Japó, el mar de Bering,[9][10] el mar d'Okhotsk[11][12] i el riu Coppermine (l'Àrtic canadenc).[4]

Pot arribar a viure 9 anys.[13]

Fase oceànica

Fase oceànica Fase d'aigua dolça (vegeu les diferències en les mandíbules i el canvi de color)

Fase d'aigua dolça (vegeu les diferències en les mandíbules i el canvi de color) El salmó reial o salmó reial del Pacífic (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) és una espècie de peix de la família dels salmònids i de l'ordre dels salmoniformes.

Losos čavyča (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum, 1792)), někdy také losos královský nebo losos stříbrný[1], je ryba z čeledi lososovitých žijící v severní části Tichého oceánu a ve sladkých vodách jeho úmoří. Patří mezi potravu kosatky dravé.

Dorůstají velikosti až 1,47 m a váhy až 60 kg.[2]

Táhnou v období od května do června. Někdy i více než 2000 km.[2]

Kazdoročně je lososů čavyča vyloveno 20 tisíc tun. Většina produkce pochází z uměle chovaných populací v akvakulturních nádržích. Maso čavyči má růžovou až červenou barvu. Zpracovává se podobně jako losos obecný.[3]

Druh je náchylný k nákaze virem způsobujícím infekční hematopoetickou nekrózu (IHN).[4]

Losos čavyča (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum, 1792)), někdy také losos královský nebo losos stříbrný, je ryba z čeledi lososovitých žijící v severní části Tichého oceánu a ve sladkých vodách jeho úmoří. Patří mezi potravu kosatky dravé.

Der Königslachs oder Quinnat (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) kommt vor allem in den Gewässern Russlands, Japans und Nordamerikas vor.

Vor der Laichwanderung ist der Rücken noch graugrün und der silberne Bauch ist mit schwarzen Flecken bedeckt. Während der Laichwanderung verändert er sein Aussehen. Der Rücken und die Seiten werden etwas bläulich und der Bauch bekommt rote Tupfen. Ältere männliche Fische können auch ganz rot werden. Männliche Königslachse können bis zu 150 cm lang und 36 kg schwer und Weibchen 120 cm lang und 20 kg schwer werden.

Die Geschlechtsreife tritt bei diesen Tieren normalerweise zwischen 4 und 6 Jahren ein. Bei Geschlechtsreife wandern die Königslachse von ihren Jagdgebieten vor der Meeresküste in ihre Heimatfließgewässer auf, wo sie schließlich laichen. Bei ihren Laichwanderungen können diese Fische über 40 km am Tag zurücklegen und 3,60 m hohe Wasserfälle überwinden. In den Flüssen legen sie Strecken bis zu 4000 km zu ihren Laichplätzen zurück. Die jungen Fische bleiben zwischen 1 und 3 Jahren im Süßwasser, bevor sie zu den Flussmündungen schwimmen.

Die weiten Wanderungen zwischen Geburtsgewässer und offenem Meer werden bei Königslachs, Rotlachs und Ketalachs auf deren Magnetsinn zurückgeführt.[1]

Jungfische fressen erst Insektenlarven und Kleinkrebse, später auch kleine Fische wie Elritzen, Groppen und Schmerlen. Erwachsene Fische hingegen ernähren sich von Krebstieren und Fischen wie Sprotten, Makrelen und Heringen.

Durch menschlichen Einfluss kommen Königslachse auch in Lebensräumen vor, die sich vom natürlichen Verbreitungsgebiet stark unterscheiden. So wurde diese Fischart seit 1967 im Bereich der Großen Seen und ihrer Zuflüsse – also in einer kompletten Süßwasser-Umgebung – angesiedelt, wo sich der Bestand seitdem gut etabliert und an die Gegebenheiten angepasst hat.[2]

Bei den Eskimos hat der Königslachs eine besondere kulturelle und religiöse Bedeutung. Er ist Nahrungsmittel und Teil der jahreszeitlichen Rituale. Unter dem Einfluss der globalen Erwärmung nehmen die Bestände in Alaska seit etwa der Jahrtausendwende massiv ab. Im Delta des Yukon River wurde 2012 ein Fangverbot als Mittel des Artenschutzes verhängt. Einheimische Eskimos hielten sich aus kulturellen Gründen nicht daran und wurden im Sommer 2013 zu absichtlich sehr geringen Strafen verurteilt. Sie haben gegen das Urteil Berufung eingelegt und hoffen, dass das Alaska Supreme Court wie in mindestens einem früheren Fall die kulturelle Subsistenz-Jagd und -Fischerei als Religionsausübung nach dem 1. Zusatzartikel zur Verfassung der Vereinigten Staaten als geschützt ansieht.[3]

Der Königslachs oder Quinnat (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) kommt vor allem in den Gewässern Russlands, Japans und Nordamerikas vor.

The Chinook salmon /ʃɪˈnʊk/ (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) is the largest and most valuable species of Pacific salmon in North America, as well as the largest in the genus Oncorhynchus.[2] Its common name is derived from the Chinookan peoples. Other vernacular names for the species include king salmon, Quinnat salmon, Tsumen, spring salmon, chrome hog, Blackmouth, and Tyee salmon. The scientific species name is based on the Russian common name chavycha (чавыча).

Chinook are anadromous fish native to the North Pacific Ocean and the river systems of western North America, ranging from California to Alaska, as well as Asian rivers ranging from northern Japan to the Palyavaam River in Arctic northeast Siberia. They have been introduced to other parts of the world, including New Zealand and Patagonia. Introduced Chinook salmon are thriving in Lake Michigan and Michigan's western rivers. A large Chinook is a prized and sought-after catch for a sporting angler. The flesh of the salmon is also highly valued for its dietary nutritional content, which includes high levels of important omega-3 fatty acids. Some populations are endangered; however, many are healthy. The Chinook salmon has not been assessed for the IUCN Red List. According to NOAA, the Chinook salmon population along the California coast is declining from factors such as overfishing, loss of freshwater and estuarine habitat, hydropower development, poor ocean conditions, and hatchery practices.[3]

Historically, the native distribution of Chinook salmon in North America ranged from the Ventura River in California in the south to Kotzebue Sound in Alaska in the north.[4] Recent studies have shown that Chinook salmon are historically native to the Guadalupe River (California) watershed, the southernmost major metropolitan area hosting salmon runs in the United States.[5] Populations have disappeared from large areas where they once flourished, however,[6] or shrunk by as much as 40 percent.[7] In some regions, their inland range has been cut off, mainly by dams and habitat alterations: in Southern California, in some areas east of the Coast Ranges of California and Oregon, and in large areas in the Snake River and upper Columbia River drainage basins.[8] In certain areas such as California's Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, it was revealed that extremely low numbers of juvenile Chinook salmon (less than 1%) were surviving.[9]

In the western Pacific, the distribution ranges from northern Japan (Hokkaido) in the south to the Arctic Ocean as far as the East Siberian Sea and Palyavaam River in the north.[8] Nevertheless, they are consistently present and the distribution is well known only in Kamchatka. Elsewhere, information is scarce, but they have a patchy presence in the Anadyr River basin and parts of the Chukchi Peninsula. Also, in parts of the northern Magadan Oblast near the Shelikhov Gulf and Penzhina Bay, stocks might persist but remain poorly studied.[8]

In 1967, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources introduced Chinook into Lake Michigan and Lake Huron to control the alewife, an invasive species of nuisance fish from the Atlantic Ocean.[10] In the 1960s, alewives constituted 90% of the biota in these lakes. Coho salmon had been introduced the year before, and the program was successful. Chinook and Coho salmon thrived on the alewives and spawned in the lakes' tributaries. After this success, Chinook were introduced into the other Great Lakes,[11] where sport fishermen prize them for their aggressive behaviour on the hook.

The species has also established itself in Patagonian waters in South America, where both introduced and escaped hatchery fish have colonized rivers and established stable spawning runs.[12] Chinook salmon have been found spawning in headwater reaches of the Rio Santa Cruz, apparently having migrated over 1,000 km (620 mi) from the ocean. The population is thought to be derived from a single stocking of juveniles in the lower river around 1930.[13]

Sporadic efforts to introduce the fish to New Zealand waters in the late 19th century were largely failures and led to no evident establishments. Initially ova were imported from the Baird hatchery of the McCloud River in California.[14] Further efforts in the early 20th century were more successful and subsequently led to the establishment of spawning runs in the rivers of Canterbury and North Otago: Rangitata River, the Opihi River, the Ashburton River, the Rakaia River, the Waimakariri River, the Hurunui River, and the Waiau Uwha River.[15] The success of the latter introductions is thought to be partly attributable to the use of ova from autumn-run populations as opposed to ova from spring-run populations used in the first attempts.[14] Whilst other salmon have also been introduced into New Zealand, only Chinook salmon (or king salmon as it is known locally in New Zealand) have established sizeable pelagic runs.

The Chinook is blue-green, red, or purple on the back and on the top of the head, with silvery sides and white ventral surfaces. It has black spots on its tail and the upper half of its body. Although spots are seen on the tail in pink salmon and silver on the tail in coho and chum salmon, Chinook are unique among the Pacific salmon in combining black spots and silver on the tail. Another distinctive feature is a black gum line that is present in both salt and fresh water.[16] Adult fish typically range in size from 24 to 36 in (61 to 91 cm), but may be up to 58 in (150 cm) in length; they average 10 to 50 lb (4.5 to 22.7 kg), but may reach 130 lb (59 kg). The meat can be either pink or white, depending on what the salmon have been feeding on.

Chinook salmon are the largest of the Pacific salmon. In the Kenai River of Alaska, mature Chinook averaged 16.8 kg (37 lb).[17] The current sport-caught world record, 97.25 lb (44.11 kg), was caught on May 17, 1985, in the Kenai River. The commercial catch world record is 126 lb (57 kg) caught near Rivers Inlet, British Columbia, in the late 1970s.[18]

Chinook, like many other species of salmon, are considered euryhaline, and thus live in both saltwater and freshwater environments throughout their life. Once hatching, salmon spend one to eight years in the ocean (averaging from three to four years)[19] before returning to their home rivers to spawn. The salmon undergo radical morphological changes as they prepare for the spawning event ahead. Salmon lose the silvery blue they had as ocean fish, and their color darkens, sometimes with a radical change in hue. Salmon are sexually dimorphic, and the male salmon develop canine-like teeth, and their jaws develop a pronounced curve or hook called a "kype."[20] Studies have shown that larger and more dominant male salmon have a reproductive advantage as female Chinook are often more aggressive toward smaller males.[21]

Chinook spawn in larger and deeper waters than other salmon species and can be found on the spawning redds (nests) from September to December. The female salmon may lay her eggs in four to five nesting pockets within a redd. After laying eggs, females guard the redd from four to 25 days before dying, while males seek additional mates. Chinook eggs hatch 90 to 150 days after deposition, depending upon water temperature. Egg deposits are timed to ensure the young salmon fry emerge during an appropriate season for survival and growth. Fry and parr (young fish) usually stay in fresh water for 12 to 18 months before traveling downstream to estuaries, where they remain as smolts for several months. Some Chinook return to fresh water one or two years earlier than their counterparts and are referred to as "jack" salmon. "Jack" salmon are typically less than 24 inches (61 cm) long but are sexually mature.

The Yukon River has the longest freshwater migration route of any salmon, over 3,000 km (1,900 mi) from its mouth in the Bering Sea to spawning grounds upstream of Whitehorse, Yukon.[22] Since Chinook rely on fat reserves for energy upon re-entering fresh water, commercial fish caught here are highly prized for their unusually high levels of heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids. However, the high costs of harvest and transport from this rural area limits its affordability. The highest elevation Chinook spawn is in the Middle Fork and Upper Salmon River in Idaho. These fish travel over 7,000 feet (2,100 m) in elevation, and over 900 miles (1,400 km), in their migration through eight dams and reservoirs on the Columbia and Lower Snake Rivers.

Chinook eat amphipods and other crustaceans and insects while young, and primarily other fish when older. Young salmon feed in streambeds for a short period until they are strong enough to journey out to the ocean and acquire more food. Chinook juveniles divide into two types: ocean-type and stream-type. Ocean-type Chinook migrate to salt water in their first year. Stream-type salmon spend one full year in fresh water before migrating to the ocean. After a few years in the ocean, adult salmon, then large enough to escape most predators, return to their natal streambeds to mate. Chinook can have extended lifespans, in which some fish spend one to five years in the ocean, reaching age eight. More northerly populations tend to have longer lives.

Salmon need suitable spawning habitat. Clean, cool, oxygenated, sediment-free fresh water is essential for egg development. Chinook use larger sediment (gravel) sizes for spawning than other Pacific salmon. Riparian vegetation and woody debris help juvenile salmon by providing cover and maintaining low water temperatures.

Chinook also need healthy ocean habitats. Juvenile salmon grow in clean, productive estuarine environments and gain the energy for migration. Later, they change physiologically to live in salt water. They rely on eelgrass and seaweeds for camouflage (protection from predators), shelter, and foraging habitat as they make their way to the open ocean. Adult fish need a rich, open ocean habitat to acquire the strength needed to travel back upstream, escape predators, and reproduce before dying. In his book King of Fish, David Montgomery writes, "The reserves of fish at sea are important to restocking rivers disturbed by natural catastrophes." Thus, it is vitally important for the fish to reach the oceans to grow into healthy adult fish to sustain the species without being impeded by man-made structures such as dams.

The bodies of water for salmon habitat must be clean and oxygenated. One sign of high productivity and growth rate in the oceans is the level of algae. Increased algal levels lead to higher levels of carbon dioxide in the water, which transfers into living organisms, fostering underwater plants and small organisms, which salmon eat.[23] Algae can filter high levels of toxins and pollutants. Thus, it is essential for algae and other water-filtering agents not to be destroyed in the oceans because they contribute to the well-being of the food chain.

With some populations endangered, precautions are necessary to prevent overfishing and habitat destruction, including appropriate management of hydroelectric and irrigation projects. If too few fish remain because of fishing and land management practices, salmon have more difficulty reproducing. When one of these factors is compromised, affected stock can decline. One Seattle Times article states, "Pacific salmon have disappeared from 40 percent of their historic range outside Alaska," and concludes it is imperative for people to realize the needs of salmon and try not to contribute to destructive practices that harm salmon runs.[7]

In the Pacific Northwest, the summer runs of especially large Chinook once common (before dams and overfishing led to declines) were known as June hogs.

A Chinook's birthplace and later evolution can be tracked by looking at its otolith (ear) bone. The bone can record the chemical composition of the water the fish had lived in, just as a tree's growth rings provide hints about dry and wet years. The bone is built with the chemical signature of the environment that hosted the fish. Researchers were able to tell where different individuals of Chinook were born and lived in the first year of their lives. Testing was done by measuring the strontium in the bones. Strontium can accurately show researchers the exact location and time of a fish swimming in a river.[24]

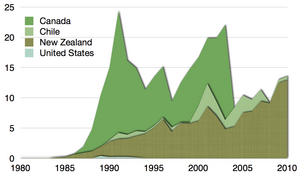

The total North Pacific fisheries harvest of the Chinook salmon in 2010 was some 1.4 million fish, corresponding to 7,000 tonnes; 1.1 million of the fish were captured in the United States, and others were divided by Canada and Russia. The share of Chinook salmon from the total commercial Pacific salmon harvest was less than 1% by weight and only about 0.3% of the number of fish.[26] The trend has been down in the captures compared to the period before 1990, when the total harvest had been around 25,000 tonnes. Global production has, however, remained at a stable level because of increased aquaculture.[25]

The world's largest producer and market supplier of Chinook salmon is New Zealand. In 2009, New Zealand exported 5,088 tonnes (5,088 t) of Chinook salmon, marketed as king salmon, equating to a value of NZ$61 million in export earnings. For the year ended March 2011, this amount had increased to NZ$85 million.[27][28] New Zealand accounts for about half of the global production of Chinook salmon, and about half of New Zealand's production is exported. Japan is New Zealand's largest export market, with stock also being supplied to other countries of the Pacific Rim, including Australia.[29]

Farming of the species in New Zealand began in the 1970s when hatcheries were initially set up to enhance and support wild fish stocks, with the first commercial operations starting in 1976.[14] After some opposition against their establishment by societal groups, including anglers, the first sea cage farm was established in 1983 at Big Glory Bay in Stewart Island by British Petroleum NZ Ltd.[14][29] Today, the salmon are hatched in land-based hatcheries (several of which exist) and transferred to sea cages or freshwater farms, where they are grown out to the harvestable size of 3–4 kilograms (6.6–8.8 lb). The broodstock for the farms is usually selected from existing farm stock or sometimes sourced from wild populations. Eggs and milt are stripped manually from sexually mature salmon and incubated under conditions replicating the streams and rivers where the salmon would spawn naturally (at around 10–12 °C or 50–54 °F). After hatching, the baby salmon are typically grown to the smolt stage (around six months of age) before they are transferred to the sea cages or ponds.[28] Most sea cage farming occurs in the Marlborough Sounds, Stewart Island, and Akaroa Harbour, while freshwater operations in Canterbury, Otago, and Tasman use ponds, raceways, and hydro canals for grow-out operations.[27] Low stocking densities, ranging between less than 1 kg/m3 and around 25 kg/m3 (depending on the life stage of the salmon), and the absence of disease in the fish mean New Zealand farmers do not need to use antibiotics or vaccines to maintain the health of their salmon stocks. The salmon are fed food pellets of fish meal specially formulated for Chinook salmon (typical proportions of the feed are: 45% protein, 22% fat, and 14% carbohydrate plus ash and water) that contain no steroids or other growth enhancers.[27][28]

Regulations and monitoring programmes ensure salmon are farmed in a sustainable manner. The planning and approval process for new salmon farms in New Zealand considers the farm's potential environmental effects, its effects on fishing activities (if it is a marine farm), and any possible cultural and social effects. In the interest of fish welfare, a number of New Zealand salmon farming operations anaesthetise salmon before slaughter using Aqui-S™, an organically based anaesthetic developed in New Zealand that is safe for use in food and that has been favourably reported on by the British Humane Slaughter Association. In recognition of the sustainable, environmentally conscious practices, the New Zealand salmon farming industry has been acknowledged as the world's greenest by the Global Aquaculture Performance Index.[30]

Chile is the only country other than New Zealand currently producing significant quantities of farmed Chinook salmon.[25] The United States has not produced farmed Chinook in commercial quantities since 1994.[25] In Canada, most commercial Chinook salmon farming ceased by 2009.[31]

Fisheries in the U.S. and Canada are limited by impacts to weak and endangered salmon runs. Nine populations of Chinook salmon are listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) as either threatened or endangered.[32] In the Snake River, Spring/Summer Chinook and Fall Chinook are ESA listed as Threatened.[33] The fall and late-fall runs in the Central Valley population in California is a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) species of concern.

In April 2008, commercial fisheries in both Oregon and California were closed in response to the low count of Chinook salmon present because of the collapse of the Sacramento River run, one of the biggest south of the Columbia.[34] In April 2009, California again canceled the season.[35] The Pacific Fishery Management Council's goal for the Sacramento River run is an escapement total (fish that return to freshwater spawn areas and hatcheries) of 122,000–180,000 fish. The 2007 escapement was estimated at 88,000, and the 2008 estimate was 66,000 fish.[36] Scientists from universities and federal, state, and tribal agencies concluded the 2004 and 2005 broods were harmed by poor ocean conditions in 2005 and 2006, in addition to "a long-term, steady degradation of the freshwater and estuarine environment." Such conditions included weak upwelling, warm sea surface temperatures, and low densities of food.[36]

In Oregon, the 2010 spring Chinook run was forecast to increase by up to 150% over 2009 populations, growing from 200,000 to over 500,000, making this the largest run in recorded history. Lower temperatures in 2008 North Pacific waters brought in fatter plankton, which, along with greater outflows of Columbia River water, fed the resurgent populations. The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife estimated 80% were hatchery-born. Chinook runs in other habitats have not recovered proportionately.[37]

In April 2016, Coleman National Fish Hatchery outside of Red Bluff, California, released 12 million juvenile Chinook salmon, with many salmon being tagged for monitoring. The release was done in hopes of helping restore the salmon population of Battle Creek.[38][39]

In June 2021, the California State Water Resources Control Board approved a plan by the United States Bureau of Reclamation to release water from Lake Shasta for irrigation use, which "significantly" increased the risk of extinction of winter-run Chinook in the Sacramento River.[40]

Introduced Chinook salmon in Lake Michigan are sought after by tourists enjoying chartered fishing trips.[41] A 2016 survey of Wisconsin anglers found they would, on average, pay $140 for a trip to catch Chinook salmon, $90 for lake trout, and $180 for walleye.[42] Should the Chinook salmon fishery collapse and be replaced with a native lake trout fishery, the economic value would decrease by 80%.[43]

Since the later 1970s, the size and age range of Chinook salmon have been declining[44] according to studies along the northwest Pacific coast from Alaska to California for the years of 1977 to 2015 which examined about 1.5 million Chinook salmon.[44] Ocean-5 Chinook (which means the fish has spent five years in the ocean) have declined from being up to 3–5% of the population to being almost none.[44] Ocean-4 chinook are also seeing a rapid decline in their population.[44] This means that Chinook are not living as long as they used to. This trend has mostly been seen in Alaska, but also Oregon and Washington.[44]

New trends have also been seen regarding the size of Ocean-1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 from 1975 to 2015. The size of Chinook who have spent one and two years in the ocean has been rising, while the size of Chinook of three to five years has been declining.[44] The size increase was seen mainly in hatchery fish, not wild, and hatchery fish were often larger than wild, but the decrease was seen in both types of populations.[44] Factors have been discovered that have influenced the size of the Chinook. They include, but are not limited to, the years they spent in fresh water before migrating to the ocean, the time of year they were caught, which season run they participated in, and where they were caught.[44] However, what is causing these negative trends is still not fully known or researched. Some possibilities can be climate change, pollution, and fishing practices.[44]

In California specifically, Chinook populations in the rivers have been declining.[45] Chinook that are migratory are already more vulnerable, and the California drought made them even more vulnerable. A study was done specifically on the California Delta over three years, and it was discovered that the Chinook salmon had a low survival rate for different reasons, and as a result, the Chinook salmon population here has been on a decline.[45] Some of the factors affecting the populations include the route used during migration, drought conditions, the amount of snowmelt, and infrastructure that affects the flow of water (such as dams and levees).[45] Each of these factors has significantly impacted Chinook survival rates, as most have made it more challenging for Chinook to travel from their spawning grounds to the ocean and back. The fluctuation of water depth as well as temperature have made this more challenging, and as a result, Chinook populations are declining. Which rivers or streams the Chinook are in highly impacts their survival rates, as some, like the Chinook in the Fraser River, only have a 30% survival rate.[45] More studies and actions are needed for there to be an impact on the survival rates of the Chinook. Due to many of these reasons, the National Wildlife Federation has listed Chinook populations as endangered or threatened.[46]

The Chinook salmon is spiritually and culturally prized among certain First Nations peoples. For tribes on the Northwest coast, salmon were an important part of their culture for spiritual reasons and food.[47] Many celebrate the first spring Chinook caught each year with "first-salmon ceremonies." While salmon fishing in general remains important economically for many tribal communities, it is especially the Chinook harvest that is typically the most valuable. The relation to salmon for the tribes in this area is similar to how other tribes relied more on buffalo for food, and have many legends and spiritual ties to them.[47]

Chinook salmon were described and enthusiastically eaten by the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Lewis wrote that, when fresh, they tasted better than any other fish he had ever eaten. They did not particularly like dried or "pounded" salmon.[48] Lewis and Clark knew about Pacific salmon but had never seen one. The Western world had known about Pacific salmon since the late 18th century. Maritime fur traders and explorers, such as George Vancouver, frequently acquired salmon by trade with the indigenous people of the Northwest coast.[49] Lewis and Clark first encountered Chinook salmon as a gift from Chief Cameahwait, on August 13, 1805, near Lemhi Pass. Tasting it convinced Lewis they had crossed the continental divide.[50]

In Oregon, the Klamath tribes have lived along the Klamath river, and the Chinook salmon have been a large part of their lives.[51] An Indian legend of a tribe on the Klamath river describes how the construction of the dam has hurt the fish population and that the impact on them has gone unnoticed, and the destruction of the dam is what has brought back their food supply and made them happy again.[51] The Klamath tribe had a similar legend that has illustrated the importance of not messing up the Chinook salmon migration.[51] The legend described three Skookums which can be related to the three dams on the Klamath river in California.[51] It has been known that the creation of dams has negatively impacted the lives of many Native American Indians by disrupting their food supply and the flow of water. The impact on the salmon migration has been seen by not only tribal members but others as well, and as a result, progress is slowly being made to help restore the salmon habitats along the river.[51] It has been known that for many tribes Chinook salmon have played an important role, spiritually and physically.

Other tribes, including the Nuxalk, Kwakiutl, and Kyuquot, relied primarily on Chinook to eat.[52] Known as the "king salmon" in Alaska for its large size and flavorful flesh, the Chinook is the state fish of this state,[53] and of Oregon.[54]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) The Chinook salmon /ʃɪˈnʊk/ (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) is the largest and most valuable species of Pacific salmon in North America, as well as the largest in the genus Oncorhynchus. Its common name is derived from the Chinookan peoples. Other vernacular names for the species include king salmon, Quinnat salmon, Tsumen, spring salmon, chrome hog, Blackmouth, and Tyee salmon. The scientific species name is based on the Russian common name chavycha (чавыча).

Chinook are anadromous fish native to the North Pacific Ocean and the river systems of western North America, ranging from California to Alaska, as well as Asian rivers ranging from northern Japan to the Palyavaam River in Arctic northeast Siberia. They have been introduced to other parts of the world, including New Zealand and Patagonia. Introduced Chinook salmon are thriving in Lake Michigan and Michigan's western rivers. A large Chinook is a prized and sought-after catch for a sporting angler. The flesh of the salmon is also highly valued for its dietary nutritional content, which includes high levels of important omega-3 fatty acids. Some populations are endangered; however, many are healthy. The Chinook salmon has not been assessed for the IUCN Red List. According to NOAA, the Chinook salmon population along the California coast is declining from factors such as overfishing, loss of freshwater and estuarine habitat, hydropower development, poor ocean conditions, and hatchery practices.

El salmón real (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), chinuc o chinook (por su nombre en inglés), es un pez de la familia de los Salmonidae que se encuentra en las áreas costeras del océano Pacífico, entre California y Japón. Animal eurihalino, vive en el mar pero migra remontando los ríos para reproducirse (anádromo). Es muy valorado por su relativa escasez.

Adulto mide entre 84 y 147 cm de longitud y pesa entre 25 y 60 kg. Es azul verdoso sobre el lomo y la cabeza, plateado en los flancos y blanco en el vientre. Presenta puntos negros en la cola y en la parte superior sel cuerpo; su boca es gris obscura.

El récord de captura en pesca deportiva es de 44,1 kg) registrado por el pescador Les Anderson en el río Kenai, Alaska, en 1985. En la pesca comercial el récord es de 57 kg registrado cerca de Petersburg, Alaska en una captura en 1949.[1]

Puede pasar entre tres y cinco años en el océano antes de retornar por los ríos para procrear y desovar en las aguas dulces donde nacieron. Prefiere corrientes más grandes y profundas que otras especies de salmón, y su desove ocurre entre septiembre y diciembre. (Hasta marzo en Chile).

Una vez en las partes altas de la corriente de agua dulce, la hembra elige al macho con el cual se reproducirá. Su selección se basa en las dimensiones físicas del varón. La hembra elige una zona de la cama del río en el cual haya grava en abundancia y allí cava un hueco poco profundo con la cola, mientras que el macho danza frente ella y hace vibrar su cuerpo. El número de huevos oscilan entre los 3 mil y 14 mil según el tamaño de la hembra y el macho los fertiliza súbitamente cuando ella los deposita.

La hembra protege los huevos entre 4 y 25 días mientras que el macho busca otras hembras. Ambos padres mueren tras reproducirse. De acuerdo con la temperatura del agua, los huevos se incuban entre 90 y 150 días antes de nacer los alevines. Después de 12 a 18 meses los ejemplares juveniles comienzan su migración hacia el mar.

Durante el período de la reproducción sufre algunas transformaciones morfológicas. Ambos sexos adquieren durante este tiempo una tonalidad rojiza brillante sobre los flancos, más intensa en los machos, que sufren incluso la modificación de la espalda, que se eleva y de la mandíbula inferior que curva hacia arriba e impide que la boca se cierre. Este crecimiento de la mandíbula vuelve prácticamente imposible que los adultos puedan alimentarse durante la fase de la reproducción, de manera que desde que empiezan su migración estacional hacia las fuentes de los ríos para reproducirse mantienen un ayuno absoluto.

Se encuentra desde la bahía de San Francisco en California hacia el norte siguiendo la costa pacífica de Estados Unidos, Canadá y Alaska, el estrecho de Bering y el mar de Chukchi, el nororiente de Siberia, Rusia, la península de Kamchatka, las Islas Kuriles y las islas del Japón.

En 1967, el Departamento de Recursos Naturales de Míchigan soltó salmones reales en el lago Míchigan y en el lago Hurón para controlar la pinchagua o «tabernera» una especie invasiva procedente del océano Atlántico. Después de culminar con éxito esta implantación los salmones reales fueron llevados a otros de los Grandes Lagos,[2] donde son apreciados para la pesca deportiva.

La especie se ha introducido en las costas de la Patagonia de Chile y Argentina donde ha colonizado ríos y establecido lugares estables de desove. También fue llevada con éxito a Nueva Zelanda.[3]

El río Yukón registra la más larga ruta de migración del salmón, más de 3 000 km desde el mar de Bering hasta las fuentes cerca de Whitehorse. Se construyó un canal en la represa hidroeléctrica del lago Schwatka para garantizar el paso y la reproducción del salmón real en Whitehorse.

El salmón real necesita para sobrevivir:

Toma del plancton para su alimentación diatomeas, copépodos, laminariales y macroalgas; además consume medusas, estrellas de mar, insectos, amfipódos, y otros crustáceos; y cuando está adulto se alimenta también de otros peces.

Las aguas limpias son esenciales para el desove. La vegetación ribereña ayuda a mantener las condiciones de las aguas para la reproducción y la vida juvenil del salmón real.

Algunas poblaciones de salmón de Estados Unidos están en la lista de especies amenazadas, por ejemplo la del Valle Central de California. En abril de 2008 tanto en Oregón como en California debió cancelarse la temporada de pesca debido a la baja población registrada. En el río Sacramento la población de la especie está al borde del colapso.[4]

El salmón real es espiritual y culturalmente muy preciado por los pueblos indígenas de las regiones donde habita originalmente, que celebren «ceremonias del salmón» en la primavera. Fue descrito y además consumido con entusiasmo por la expedición de Lewis y Clark (1804-06). La importancia económica para las comunidades indígenas y para otras poblaciones es muy grande. Es apreciado por su color, sabor, textura y alto contenido de aceite Omega-3.[5]

El salmón real (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), chinuc o chinook (por su nombre en inglés), es un pez de la familia de los Salmonidae que se encuentra en las áreas costeras del océano Pacífico, entre California y Japón. Animal eurihalino, vive en el mar pero migra remontando los ríos para reproducirse (anádromo). Es muy valorado por su relativa escasez.

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha Oncorhynchus generoko animalia da. Arrainen barruko Salmonidae familian sailkatzen da.

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha Oncorhynchus generoko animalia da. Arrainen barruko Salmonidae familian sailkatzen da.

Kuningaslohi (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) on tyynenmerenlohten sukuun kuuluva suuri kala. Se voi kasvaa puolitoistametriseksi ja 45–50-kiloiseksi. Kuningaslohen alkuperäistä asuinaluetta on pohjoinen Tyynimeri Japanista ja Koreasta aina Kaliforniaan asti. Nykyään kuningaslohta elää istutettuna eri puolilla maailmaa mm. Uudessa-Seelannissa.

Kuningaslohta on yritetty kotiuttaa myös Eurooppaan, aina tuloksetta. Suomessa istutuksia tehtiin vuosina 1935–1937 Kokemäenjokeen, Oulujokeen, Höytiäiseen ja eräisiin Pohjanmaan pienempiin jokiin. Luonnollinen lisääntyminen ei koskaan käynnistynyt.

Kuningaslohi (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) on tyynenmerenlohten sukuun kuuluva suuri kala. Se voi kasvaa puolitoistametriseksi ja 45–50-kiloiseksi. Kuningaslohen alkuperäistä asuinaluetta on pohjoinen Tyynimeri Japanista ja Koreasta aina Kaliforniaan asti. Nykyään kuningaslohta elää istutettuna eri puolilla maailmaa mm. Uudessa-Seelannissa.

Kuningaslohta on yritetty kotiuttaa myös Eurooppaan, aina tuloksetta. Suomessa istutuksia tehtiin vuosina 1935–1937 Kokemäenjokeen, Oulujokeen, Höytiäiseen ja eräisiin Pohjanmaan pienempiin jokiin. Luonnollinen lisääntyminen ei koskaan käynnistynyt.

Saumon royal

Le saumon royal, saumon chinook, ou saumon quinnat (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) est une espèce de poissons anadromes présents dans les eaux du nord de l'océan Pacifique. Il était autrefois présent dans les fleuves de la façade pacifique de l'Alaska à la Californie. Il en existe aussi des populations au Japon et dans les South Island de Nouvelle-Zélande.

C'est le plus grand des saumons américains. Il est aussi apprécié pour sa richesse en omega 3. C'est l'une des espèces de saumons nord-américaines les plus appréciées des pêcheurs sportifs.

Ce saumon peut atteindre 1,5 m pour plus de 60 kg et une longévité de 9 ans.

Le Chinook est bleu-vert, violet sur le dos et le dessus de la tête avec les flancs argentés et le ventre blanc. Il porte des taches noires sur la queue et la moitié supérieure de son corps. Sa bouche est souvent de couleur violet foncé.

Le record actuel homologué en pêche sportive est de 45 kg pour un saumon capturé en 2002 dans le fleuve Skeena (Skeena river, Terrace, Colombie-Britannique). Pour les années récentes, le record mondial de capture commerciale homologué serait de 54 kg, pêché près du Fjord Rivers Inlet au nord-est du Canada en Colombie-Britannique dans les années 1970[1].

Dans le patois de la région Pacifique du Nord-Ouest des États-Unis, les « Hogs » sont les saumons capturés lors de leur remontée migratoire. Dans cette région, l'été surtout, on pêchait de très grands saumons dits « June Hogs ». C'était l'une des principales ressources en poisson des peuples des Premières nations nord-amérindiennes. Ces saumons furent rapidement très appréciés des pêcheurs sportifs canadiens et américains, ainsi que des conserveries de saumon installées sur le fleuve Columbia et ses affluents. Ils ont disparu avec la surpêche et la construction des grands barrages. Aujourd'hui le plus grand Chinook pris dans les mêmes conditions sont deux fois plus petits que les « June hogs » capturés moins d'un siècle plus tôt.

Ce saumon peut passer de 1 à 8 ans dans l'océan (3 à 4 ans en moyenne[2]) avant de remonter vers les sources de sa rivière natale pour frayer. Les Chinook se reproduisent dans les eaux nettement plus profondes que d'autres espèces de saumons. Le frai est déposé dans un nid sur le fond, de septembre à décembre. Après la ponte, les femelles gardent leur ponte 4 à 25 jours avant de mourir, tandis que les mâles cherchent à continuer à se reproduire. L'éclosion a lieu - selon la température de l'eau - 90 à 150 jours après la ponte. Les larves émergent au printemps, saison appropriée pour leur survie et croissance. Les larves et tacons (jeunes poissons) passent 12 à 18 mois en eau douce avant d'entamer leur dévalaison vers les estuaires, où ils grossissent (comme saumoneaux) durant plusieurs mois. Certains Chinook retournent vivre un ou deux ans après en eau douce, plus tôt que leurs homologues, et sont dits "Jack" (ils font la moitié de la taille d'un saumon adulte de la même espèce). Les pêcheurs sportifs les relâchent généralement, alors que les pêcheurs commerciaux les conservent[2].

Cette espèce vit de la baie de Monterey (Californie du nord) au détroit de Béring (Alaska) et jusque dans les eaux arctiques du Canada et de la Russie (Mer de Tchoukotka). Des populations se produisent en Asie jusqu'au sud des îles du Japon. Il y en a au Québec dans des lacs, des rivières et dans le fleuve St-Laurent. En Russie, on les trouve dans le Kamtchatka et les îles Kouriles, mais ils ont disparu d'une grande partie de leur aire de répartition[3]. Au moins 40 % des populations ont disparu[4].

L'espèce a été réintroduite dans le lac Michigan et le lac Huron en 1967 par le Michigan Department of Natural Resources pour y contrôler le gaspareau, espèce atlantique devenue invasive après avoir été introduite dans les lacs où à cette époque il constituait environ 90 % du biote. Les saumons argentés (ou saumons coho), avaient été implantés avec succès l'année précédente et le chinook s'y est également réinstallé, jusque dans les affluents des lacs. Après ce succès, le saumon chinook a été implanté ou réimplanté dans les autres Grands Lacs[5] où les pêcheurs sportifs l'ont apprécié pour sa résistance.

L'espèce est aussi apparue dans les eaux de Patagonie (Amérique du Sud, à partir d'individus relâchés ou échappés d'élevages. Ils y ont colonisé plusieurs fleuves où l'on observe maintenant des montaisons stables.

Des efforts sporadiques ont été faits dès la fin des années 1800 pour l'introduire en Nouvelle-Zélande avec plusieurs échecs successifs. Des tentatives ou réussites (à partir d'œufs ou alevins implantés dans les cours d'eau) ont eu lieu en Californie[6] dès les années 1900, plus efficacement par la suite dans les rivières de Cantebury et North Otago ; Rangitata, la rivière Opihi, la rivière Ashburton, la rivière Rakaia, la rivière Waimakariri, le fleuve Hurunui et la rivière Waiau[7]. On a attribué un taux de succès plus élevé pour les introductions récentes au fait qu'on a utilisé des ovules prélevés en automne plutôt qu'au printemps comme au lors des premières tentatives[6]. Le Chinook et d'autres saumons ont aussi été introduits en Nouvelle-Zélande.

C'est dans le fleuve Yukon qu'est effectuée la plus longue route migratoire pour cette espèce (plus de 3 000 kilomètres, soit 1 900 milles de son embouchure dans la mer de Béring aux frayères située en amont de Whitehorse, dans le Yukon. Ces chinooks doivent compter sur d'importantes réserves de graisse pour avoir assez d'énergie pour franchir les nombreux obstacles qui les séparent de leurs frayères, et sont réputés être plus riches qu'ailleurs en acides gras oméga-3.

Dans le cadre d'un projet d'environ 600 millions de US dollars, sur le fleuve Columbia des puces RFID sont utilisées depuis 1986 pour étudier les corridors écologiques de migration et les dates et vitesse de migration des saumons chinook dans un réseau hydrogrphique qui compte divers obstacles naturels et environ 400 retenues d'eau plus ou moins artificielles sur son parcours (fleuve et affluents)[8]. Une boucle du fleuve entoure le plus vaste complexe nucléaire américain (initialement construit pour produire le plutonium des bombes atomiques) et devenu le plus grand site de dépôt de déchets nucléaires, le site ayant libéré quand il était en activité une importante pollution radioactive dans ce fleuve, qui a notamment touché les saumons. Les 14 sous-espèces de chinook sont en disparition ou fort déclin, mais pas uniquement dans ce fleuve. Elles se sont dans tous les cours d'eau du Nord-Ouest du Pacifique où elles étaient encore abondantes il y a 2 ou 3 siècles, de même que la plupart des saumons dans le monde). Dans le fleuve Columbia près de deux millions de saumons ont ainsi été piégés et « taggés » puis relâchés chaque année depuis 1986[8] ce qui a permis de repérer les zones dangereuses pour les poissons et d'y réduire les taux de mortalité de 15 à 20 %[8].

Cette espèce dont on trouvait autrefois de très gros individus intéressent l'industrie du génie génétique qui espèrent y trouver des gènes permettant de faire grossir d'autres poissons (comme le « saumon AquAdvantage » qui fait depuis plusieurs années l'objet d'une demande de mise sur le marché aux États-Unis)

Saumon royal

Le saumon royal, saumon chinook, ou saumon quinnat (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) est une espèce de poissons anadromes présents dans les eaux du nord de l'océan Pacifique. Il était autrefois présent dans les fleuves de la façade pacifique de l'Alaska à la Californie. Il en existe aussi des populations au Japon et dans les South Island de Nouvelle-Zélande.

C'est le plus grand des saumons américains. Il est aussi apprécié pour sa richesse en omega 3. C'est l'une des espèces de saumons nord-américaines les plus appréciées des pêcheurs sportifs.

O salmón real,[1] ou salmón chinook, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha,[2] é un peixe osteíctio da familia dos salmónidos, subfamilia dos salmoninos, que se atopa nas áreas costeiras do océano Pacífico, entre California e o Xapón.

Animal eurihalino, vive no mar e migra remontando os ríos para reproducirse (anádromo).

É moi valorado pola súa relativa escaseza.

O adulto mide entre 84 e 147 cm de lonxitude e pesa entre 25 e 60 kg.

A marca de captura en pesca deportiva é de 44,1 kg, rexistrada polo pescador Les Anderson no río Kenai, Alasca, en 1985. Na pesca comercial o récord é de 57 kg, rexistrado preto de Petersburg, Alasca nunha captura en 1949.[3]

É de cor azul verdosa sobre o lombo e a cabeza, prateada nos flancos e branca no ventre. Presenta puntos negros na cola e na parte superior do corpo; a súa boca é gris escura.

Pode pasar entre tres e cinco anos no océano antes de retornar polos ríos para procrear e desovar nas augas doces onde naceron. Prefire correntes máis grandes e profundas que outras especies de salmón; a desova ocorre entre setembro e decembro.

Unha vez nas partes altas da corrente de auga doce, a femia elixe o macho co cal se reproducirá. A súa selección baséase nas dimensións físicas do macho. A femia elixe unha zona da cama do río na cal haxa grava en abundancia e alí cava un burato pouco profundo coa cola, mentres que o macho danza fronte ela e fai vibrar o seu corpo. O número de ovos de oscilan entre os 3 mil e 14 mil segundo o tamaño da femia, e o macho fertilízaos subitamente cando ela os deposita.

Ambos os pais morren tras reproducírense. De acordo coa temperatura da auga, os ovos incúbanse entre 90 e 150 días antes de nacer as crías. Despois de 12 a 18 meses os exemplares xuvenís comezan a súa migración cara ao mar.

Durante o período da reprodución sofre algunhas transformacións morfolóxicas. Ambos os dous sexos adquiren durante este tempo unha tonalidade avermellada rechamante sobre os flancos, máis intensa nos machos, que sofren mesmo a modificación nas costas, que se elevan, e da mandíbula inferior, que curva cara a arriba e impide que a boca se peche. Este crecemento da mandíbula volve practicamente imposible que os adultos poidan alimentarse durante a fase da reprodución, de xeito que dende que empezan a súa migración estacional cara ás fontes dos ríos para reproducírense manteñen un xaxún absoluto.

Distribúese dende a baía de San Francisco en California cara ao norte seguindo a costa pacífica dos Estados Unidos, Canadá e Alasca, o estreito de Bering e o mar de Chukchi, o nororiente de Siberia, Rusia, a península de Kamchatka, as Illas Kuriles e as illas do Xapón.

En 1967 o Departamento de Recursos Naturais de Míchigan soltou salmóns reais no lago Michigan e no lago Huron para controlar a Alosa pseudoharengus unha especie invasora procedente do océano Atlántico. Despois de culminar con éxito esta implantación os salmóns reais foron levados a outros dos Grandes Lagos,[4] onde son apreciados para a pesca deportiva.

A especie introduciuse nas costas da Patagonia chilena e arxentina, onde colonizou ríos e estableceu lugares estables de desova. Tamén foi levada con éxito a Nova Zelandia.[5]

O río Yukón rexistra a máis longa ruta de migración do salmón, de máis de 3.000 km, dende o mar de Bering até as fontes preto de Whitehorse. Construíuse unha canle na presa hidroeléctrica do lago Schwatka para garantir o paso e a reprodución do salmón real en Whitehorse.

O salmón real necesita para sobrevivir:

Toma do plancto para a súa alimentación diatomeas, copépodos, laminariais e macroalgas; ademais consome medusas, estrelas de mar, insectos, anfipódos, e outros crustáceos; e cando é adulto aliméntase tamén doutros peixes.

As augas limpas son esenciais para a desova. A vexetación ribeirega axuda a manter as condicións das augas para a reprodución e a vida xuvenil do salmón real.

Algunhas poboacións de salmón dos Estados Unidos están na lista de especies ameazadas, por exemplo a do Val Central de California. En abril de 2008 tanto en Oregón como en California debeu cancelarse a tempada de pesca debido á baixa poboación rexistrada. No río Sacramento a poboación da especie está ao bordo do colapso.[6]

O salmón real é espiritual e culturalmente moi prezado polos pobos indíxenas amerindios das rexións onde habita orixinalmente, que celebran «cerimonias do salmón» na primavera. Foi descrito e ademais consumido con entusiasmo pola expedición de Lewis e Clark (1804-06). A importancia económica para as comunidades indíxenas e para outras poboacións é moi grande. É apreciado pola súa cor, sabor, textura e alto contido de aceites Omega-3.[7]

O salmón real, ou salmón chinook, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, é un peixe osteíctio da familia dos salmónidos, subfamilia dos salmoninos, que se atopa nas áreas costeiras do océano Pacífico, entre California e o Xapón.

Animal eurihalino, vive no mar e migra remontando os ríos para reproducirse (anádromo).

É moi valorado pola súa relativa escaseza.

Kraljevski losos (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), riba iz porodice lososa ili pastrvki (Salmonidae) rasprostranjena na Pacifiku, u engleskom jeziku poznata kao kraljevski losos. Mrijesti u rijekama na pacifičkoj obali Amerike, sve od Point Hope, Aljaska pa do riijeke Ventura River u Kaliforniji, SAD, kao i na poluotoku kamčatka. Ova riba može narasti do 150 cmm ali joj je uobičakjena dužina 70. cm, a može dosegnuti težinu od preko 60 kg (rekordno je zabilježena težina od 61.4 kg.)

O. tshawytscha je veoma značajna u prehrani indijanskog stanovništva sa Sjeverozapadnog obalnog područja[1], a plemena su imala svoja ribolovna područja, a njezina pojava izazivala je pokrete čitavog stanovništva.

O. tshawytscha je poznata zbog svog značaja pod brojnim nazivima, među kojima su globalni FAO nazivi Chinook salmon i King salmon, a kako se mrijesti i na poluotoku Kamčatka u Rusiji i tamo je poznata kao čaviča (чавыча)[2], koji je i postao znanstveni naziv za ovu vrstu.

Kraljevski losos (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), riba iz porodice lososa ili pastrvki (Salmonidae) rasprostranjena na Pacifiku, u engleskom jeziku poznata kao kraljevski losos. Mrijesti u rijekama na pacifičkoj obali Amerike, sve od Point Hope, Aljaska pa do riijeke Ventura River u Kaliforniji, SAD, kao i na poluotoku kamčatka. Ova riba može narasti do 150 cmm ali joj je uobičakjena dužina 70. cm, a može dosegnuti težinu od preko 60 kg (rekordno je zabilježena težina od 61.4 kg.)

O. tshawytscha je veoma značajna u prehrani indijanskog stanovništva sa Sjeverozapadnog obalnog područja, a plemena su imala svoja ribolovna područja, a njezina pojava izazivala je pokrete čitavog stanovništva.

O. tshawytscha je poznata zbog svog značaja pod brojnim nazivima, među kojima su globalni FAO nazivi Chinook salmon i King salmon, a kako se mrijesti i na poluotoku Kamčatka u Rusiji i tamo je poznata kao čaviča (чавыча), koji je i postao znanstveni naziv za ovu vrstu.

Kóngalax (fræðiheiti: Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) er stærsta tegundin í ættbálki laxfiska.

Hann lifir við strendur Norður–Kyrrahafs og dreifist um stórt svæði, í Austur–Kyrrahafi allt frá Ventura-ánni í Kaliforníu norður til Point Hope í Norður–Alaska og í Vestur–Kyrrahafi frá Hokkaido-eyju í Japan og norður til Anadyr-fljóts í Rússlandi. Nú er tegundin reyndar horfin af stórum svæðum þar sem hún var algeng áður fyrr en það á þó aðallega við um svæði í Norður–Ameríku. Einkum er það átroðningur manna sem hefur valdið því að laxinn hefur þurft að yfirgefa fyrri heimkynni, aðallega vegna þess að byggðar hafa verið stíflur sem hafa eyðilagt búsvæði hans. [1].

Kóngalaxinn getur orðið allt að einn og hálfur metri að lengd en algeng lengd hans er um 80 sentimetrar. Þyngsti kóngalax sem veiðst hefur vó um það bil 61 kíló. Það er þó ekki algeng þyngd en vanalegt er að laxinn fari yfir 18 kíló. Útlit hans er breytilegt eftir því hvar hann er hverju sinni. Þegar hann er í sjó er hann blágrænn á bakið með silfraðar síður, litlar svartar doppur á sporði og baki og svartan neðri góm. Þegar laxinn snýr svo aftur úr sjónum og upp í ár til þess að fjölga sér verður hann brúnn eða rauður á lit. Litabreytingin verður mun meiri hjá hængnum en hrygnunni, kjaftur hængsins verður króklaga og bak hans verður kúpt. Kóngalaxinn er rauður á fiskinn en ekki bleikur eins og aðrir laxar, holdið getur þó stundum verið hvítt sem er sjaldgæft en það bragðast alveg eins og það rauða [2].

Til eru tvær gerðir af kóngalaxi, annars vegar er það hin svokallaða straumlax og hins vegar sjólax. Munurinn á þeim er ekki ýkja mikill en hann felst í því að straumlaxinn er lengur í ánum en sjólaxinn eftir að hann klekst úr eggi. Sjólaxinn kemur oftast í lok sumars og í byrjun hausts upp í árnar til þess að hrygna, þeir koma þó á öllum tíma árs þó svo að þessi tími sé algengastur, en straumlaxinn kemur mest á vorin og í byrjun sumars. Þetta hegðunarmynstur má rekja til þess að flóð og þurrkar eru algengari í suðurhluta Bandaríkjanna og því er sjólaxinn aðallega að finna þar á meðan straumlaxinn heldur til norðar þar sem hann getur dvalið lengur í ánum eftir að hann hefur klakist úr eggi[3]

Lífsferill hópanna er sams konar, ef undan er skilinn tíminn sem þeir dvelja í ánum í upphafi ævinnar. Eftir að hafa eytt byrjun ævi sinnar í ám (allt frá þremur mánuðum og upp í tvö ár), færa kóngalaxar sig á haf út þar sem þeir eru við fæðunám. Þeir halda sig samt að mestu nálægt ströndinni þótt vitað sé um fiska sem hafa farið allt að 1600 km frá landi. Meginuppistaða í fæðu kóngalaxins þegar að hann er ungur eru krabbadýr og vatna- og þurrlendisskordýr. Þegar laxinn stækkar og eldist nærist hann aðallega á öðrum fiskum eins og til dæmis lýsu og makríl. Þegar laxinn hefur náð að stækka og dafna í hafinu, snýr hann aftur upp í ána þar sem hann klaktist úr eggi til þess að fjölga sér. Algengast er að þetta gerist þegar að hann hefur verið í hafinu í um það bil tvö til fjögur ár en allt veltur þetta á því hvenær hver fiskur verður kynþroska (það getur verið allt frá tveggja ára aldri til sjö ára aldurs). Þegar hrygnan hefur fundið stað í ánni til þess að hrygna grefur hún nokkrar holur sem hún hrygnir svo í en hver hrygna getur hrygnt frá 3.000 til 14.000 eggjum. Þegar hrygnan hefur hrygnt eggjum sínum, gætir hún þeirra þar til hún drepst, hængurinn fer og finnur næstu hrygnu en að lokinni hrygningartíð drepst hann líka[4].

NOAA Fisheries, Pacific and North Pacific Fishery Management Councils, og Alaska Department of Fish and Game eru þær stofnanir sem halda mest utan um veiðar á kóngalaxi í heiminum. Þessar stofnanir fara yfir veiðitölur síðasta fiskveiðiárs og í samræmi við þær og með tilliti til stofnstærðar gefa þær út kvóta á laxinn. Markmið þeirra er að leyfa veiðimönnum að veiða eins mikið og mögulega er án þess að skaða stofninn með ofveiði, ásamt því að stuðla að því að þeir stofnar sem eru í lágmarki á ákveðnum svæðum geti fengið að dafna á ný með því að minnka veiðar á þeim svæðum. Stofnanirnar meta hversu mikill hrygningarfiskur þarf að komast af til þess að stofnstærðin viðhaldist og því er það einnig tekið með inn í reikninginn þegar kvótanum er úthlutað [5].

Eins og fyrr segir lifir kóngalaxinn í Kyrrahafi og þær þjóðir sem hafa stundað mestar veiðar á honum frá árinu 1950 eru Bandaríkin, Rússland og Kanada en Bandaríkin hafa veitt meira en tvöfalt meira en Kanada og Rússland til samans. Veiðarnar hafa verið að dragast saman á undanförnum áratugum. Helstu aðferðirnar sem notaðar eru við veiðar á kóngalaxi eru veiðar í nót, lagnet og línuveiðar með beitu sem lokkar fiskinn að önglinum. Síðastnefnda aðferðin gefur mestu vörugæðin, því fiskurinn er þá tekinn lifandi og unninn ferskur úr sjó. Einnig eru stangveiðar stundaðar af áhugamönnum. Allt eru þetta veiðarfæri sem valda ekki skaða á heimkynnum laxins og annarra lífvera á þeim stöðum sem laxinn heldur sig. Meðafli er mjög lítill og þá aðallega aðrar laxategundir. Kóngalaxinn er veiddur að mestu leyti yfir sumartímann. Á síðasta ári (2012) var gefinn út kvóti upp á 266.800 fiska þar sem að 70% kvótans mátti veiða yfir sumartímann. Kvótanum var svo skipt niður eftir veiðarfærum með eftirfarandi hætti, 4,3% af kvótanum mátti veiða með nót, 2,9% í net, 80% á beitta línu og um það bil 13% á stöng. Langmestur hluti aflans af kóngalaxi veiðist við Suðaustur–Alaska en árið 2010 veiddust þar 262 þúsund laxar.[6]

Árið 2010 var meðalverð á kíló af kóngalaxi upp úr sjó um það bil 942 íslenskar krónur, miðað við gengi á þeim tíma. Neytendur sækjast mjög eftir kóngalaxinum vegna þess hversu ríkur hann er af omega-3-fitusýrum, B12 vítamíni og próteinum. Hann er einnig feitari á fiskinn en aðrir laxar og þar með mýkri. Kóngalaxinn er seldur ferskur, frosinn, reyktur og niðursoðinn. Veiðarnar eru sjálfbærar og fyrir vikið er varan eftirsóttari. Helsti markaður fyrir kóngalax er Norður-Ameríka en mikill meiri hluti af þeim laxi sem er veiddur er seldur þangað.[7]

Kóngalax (fræðiheiti: Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) er stærsta tegundin í ættbálki laxfiska.

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum, 1792), conosciuto comunemente come salmone reale[1], è una specie di pesce osseo marino e d'acqua dolce appartenente alla famiglia Salmonidae.

Il suo areale comprende l'Oceano Pacifico settentrionale. Lungo le coste americane è presente dall'Alaska alla California (a sud fino a San Diego). Sul lato asiatico dell'oceano è presente in Giappone. Si può incontrare nel mar del Giappone, nel mar di Bering e nel mar di Okhotsk[2]. È stato introdotto nei Grandi Laghi e in alcune zone della Nuova Zelanda, dell'Australia, dell'Argentina e del Cile[3]. Come tutti i salmoni è una specie anadroma che passa gran parte della vita in mare ed effettua migrazioni riproduttive verso il tratto alto dei fiumi dove avviene la deposizione delle uova nello stesso torrente natale. Alcuni individui si accrescono nei laghi anziché in mare. I giovanili di solito scendono in mare a un anno di età ma talvolta dopo solo 3 mesi o dopo addirittura 3 anni. In mare ha abitudini epipelagiche anche se pare che possa spingersi fino a 375 metri di profondità[2].

L'aspetto di questo pesce durante la vita marina è simile a quello degli altri salmoni ma ha corpo più alto e compresso, specialmente negli individui di taglia maggiore. Il maschio riproduttivo ha dorso gibboso e mascelle incurvate. Si distingue dagli altri salmoni del Pacifico in fase marina per i piccoli punti neri che ricoprono il dorso ed entrambi i lobi della pinna caudale e per avere gengive nere nella mascella inferiore. Il dorso e la testa sono di colore da verde cupo a blu, i fianchi argentei e il ventre biancastro. La livrea riproduttiva è variabile, di solito ha toni brunastri, rossicci o rosei, molto più marcati negli individui maschili[2].

Può raggiungere i 150 cm di lunghezza, con una taglia media compresa tra i 60 e 90 cm. Il peso massimo noto è di 61.4 kg[2].

Vive fino a 9 anni[2].

I giovanili in acqua dolce catturano in prevalenza insetti e piccoli crostacei. In mare si ciba soprattutto di pesci e crostacei[2].

La migrazione riproduttiva inizia in inverno e può raggiungere una distanza massima di 4.827 km dal mare. La femmina prepara un nido scavando una buca sul fondale dopo di che viene affiancata dal maschio dominante più vicino, seguito da alcuni altri maschi non dominanti che si pongono nelle immediate vicinanze. Il maschio tocca la pinna dorsale della femmina per stimolarla. I riproduttori muoiono pochi giorni dopo la riproduzione[2].

Questo salmone è molto importante per la pesca commerciale (che lo insidia con reti a strascico e reti da posta) e per la pesca sportiva. Gli stati che catturano le maggiori quantità sono Stati Uniti e Russia. La carne è ottima, in gran parte degli esemplari ha colore rosso ma talvolta è bianca[2][4]. Le marinerie dell'Alaska che pescano questa specie hanno ricevuto la certificazione di sostenibilità e di buona gestione degli stock del Marine Stewardship Council[5].

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum, 1792), conosciuto comunemente come salmone reale, è una specie di pesce osseo marino e d'acqua dolce appartenente alla famiglia Salmonidae.

De chinookzalm of quinnat[1] (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha; afgeleid van het Russische чавыча; 'tsjavytsja'), een beenvis is de grootste van de Pacifische zalmen. De vis staat bij de Amerikanen ook bekend als koningszalm, springzalm en ettelijke andere namen. De vis kan een lengte bereiken van 150 cm en het hengelrecord was een exemplaar van 57 kg. Hij wordt bij de hengelaars beschouwd als een goede vechter en eetbare vis. De gebruikelijke gewichten liggen tussen de 9 (twee jaar op zee) en de 30 (5 à 6 jaar op zee) kg. De leeftijd van de paaiende vissen varieert van 2 tot 7 jaar. De hoogst geregistreerde leeftijd is 9 jaar.

Het verspreidingsgebied loopt van de Baai van San Francisco tot de Tsjoektsjenzee in Rusland. Ze komen op onregelmatige basis voor in noordelijke Pacifische kustwateren.

Chinooks zijn ook met succes uitgezet in Zuid-Amerika, met name Zuid-Chili, in de Grote Meren op de grens van de VS en Canada en in Nieuw-Zeeland.

De chinookzalm is een goed geproportioneerde, gestroomlijnde vis, zilverachtig aan de zijkanten en met een donkere rug. Zwarte vlekjes lopen van achter de kieuwdeksel via de rug tot aan het staartgedeelte. Ook op de rugvin en staartvin komen zwarte vlekjes voor. De chinook is relatief grofbeschubd. De flanken zijn in de winter voorzien van een purperachtig zweem, dat in de zomer zwart wordt. Een onmiskenbaar kenmerk van de chinookzalm is het zwarte tandvlees. De bek is voorzien van goed ontwikkelde scherpe tanden. Aan de vissige okselgeur kan de vis ook prima herkend worden.