Lifespan, longevity, and ageing

provided by AnAge articles

Maximum longevity: 20 years (wild)

- license

- cc-by-3.0

- copyright

- Joao Pedro de Magalhaes

- editor

- de Magalhaes, J. P.

Associations

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Small salmon sharks from 70 to 110 cm PCL are at risk of being preyed upon by larger sharks, including other salmon sharks, blue sharks (Prionace glauca), and great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias). Once maturity is reached, salmon sharks occupy the highest trophic level in the food web of subarctic waters, alongside marine mammals and seabirds. The only known predators of mature salmon sharks are humans.

Small salmon sharks are found in abundance in waters north of the subarctic boundary, which are thought to be their nursery ground. There they can avoid predation by larger sharks, which inhabit areas that are further north or south. Juveniles also display obliterate countershading, and lack the dark blotches found on the ventral areas of adults.

Known Predators:

- salmon sharks (Lamna ditropis)

- blue sharks (Prionace glauca)

- great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias)

- humans (Homo sapiens)

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Morphology

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Adult salmon sharks can weigh at least 220 kg (485 lbs). There are unofficial reports of salmon sharks weighing 450 kg (992 lbs), but it is likely that this specimen was a misidentified white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). Sharks in the eastern North Pacific have a greater weight to length ratio than their counterparts in the western North Pacific.

When reporting shark lengths, precaudal length (PCL) is often used, even though it excludes the tail fin. This allows discussion of a standardized length measure, as different possible orientations of the tail can give different measurements of total length. The PCL is determined by calculating the straight-line-distance between two vertical lines, one projected from the tip of the snout, and the other from the precaudal point. Adult salmon sharks typically range in size from 180 to 210 cm PCL.

Most fishes are ectotherms, meaning their body temperature remains identical to the surrounding water. Salmon sharks, however, are endothermic, meaning they maintain a core body temperature higher than the surrounding water (up to 16°C). This is accomplished through retention of heat produced by cell metabolism. However, no information on the basal metabolic rate of Lamna ditropis was found.

Salmon sharks have a heavy, spindle-shaped body with a short, conical snout. These sharks have relatively long gill slits. The mouth is broadly rounded, with the upper jaw containing 28 to 30 teeth and the lower jaw containing 26 to 27 moderately large, blade-like teeth with cusplets (small bumps or “mini-teeth”) on either side of each tooth. Unpaired fins consist of a large first and much smaller second dorsal fin, a small anal fins and a crescent-shaped caudal fin. The caudal fin is homocercal, meaning the dorsal and ventral lobes are nearly equal in size. Paired fins include large pectoral fins and much smaller pelvic fins, which are modified to form reproductive structures in males. A distinctive keel is present on the caudal peduncle and a short secondary keel is present on the caudal base. Dorsal and lateral areas are dark bluish-gray to black. The belly is white, and often includes various dark paatches in adults. The ventral surface of the snout is also dark-colored.

Salmon sharks can be distinguished from great white sharks (Carcarodon carcharias) by the presence of a secondary keel on the caudal base, dark coloration on the ventral surface of the snout, and dusky patches on the belly, all of which are lacking in great whites.

Salmon sharks are also similar in appearance to porbeagle sharks (Lamna nasus), but can easily be distinguished by their distributions (porbeagles are absent from the North Pacific range of salmon sharks).

Range mass: 220 (high) kg.

Range length: 140 to 215 cm.

Average length: 180-210 cm.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Life Expectancy

provided by Animal Diversity Web

The maximum age of salmon sharks has been estimated through vertebral analysis. In both western and eastern North Pacific populations longevity estimates are similar, between 20 and 30 years. Salmon sharks are not currently held in captivity in large oceanaria and there is no published information regarding their lifespan under captive conditions.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 17 to 25 years.

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 20 to 30 years.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Habitat

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Salmon sharks are primarily pelagic, but are also found in coastal waters of the North Pacific. They generally swim in the surface layer of subarctic water, but also occur in deeper waters of warmer southern regions to at least 150m. This species appears to prefer water temperatures from 2°C to 24°C.

Populations of salmon sharks show seasonal density fluctuations in the Coastal Alaska Downwelling Region, which is characterized by turbulent mixing and strong seasonality of light and temperature. The summer-autumn usage of this ecoregion by salmon sharks coincides with the return of Pacific salmon (a preferred prey item) to their spawning rivers.

Range depth: 1 to 255 m.

Average depth: 150 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; polar ; saltwater or marine

Aquatic Biomes: pelagic ; coastal

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Distribution

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Salmon sharks are widely distributed throughout coastal and pelagic environments within the subarctic and temperate North Pacific Ocean, between 10°N and 70°N latitude. Their range includes the Bering Sea, the Sea of Okhotsk, and the Sea of Japan, and also extends from the Gulf of Alaska to southern Baja California. Salmon sharks generally range from 35°N to 65°N latitude in the western Pacific ocean and from 30°N to 65°N in the eastern Pacific, with highest densities found between 50°N and 60°N.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native ); palearctic (Native ); pacific ocean (Native )

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Trophic Strategy

provided by Animal Diversity Web

The diet of salmon sharks consists of pelagic and demersal fish, mainly Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus species). Salmon sharks also consume steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii pallasii), sardines (Sardinops sagax), pollock (Theragra chalcogramma), lancetfishes (Alepisaurus ferox), daggerteeth (Anotopterus nikparini), Pacific sauries (Cololabis saira), pomfrets (Brama japonica), mackerel (Scombridae), lumpfishes (Cyclopteridae), sculpins (Cottidae), and other fish that they can capture.

Animal Foods: fish; carrion

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore )

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Associations

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Salmon sharks are apex predators in subarctic waters, helping to regulate populations of their prey species within the ecosystem.

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

- flatworms (Nybelinia surmenicola)

- nematodes (Anisakis simplex)

- copepods (Anthosoma crassum)

- copepods (Echthrogleus coleopteratus)

- copepods (Dinemoura latifolia)

- copepods (Dinemoura affinis)

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Benefits

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Shark meat and shark fins have high economic value and salmon sharks are often caught by commercial fisheries, although this is often as bycatch in pursuit of other species. In Japan, their hearts are used for sashimi. They are also caught by sports fishermen for recreation.

Positive Impacts: food

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Benefits

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Salmon sharks, when caught unintentionally as bycatch, cause problems for commercial salmon fishermen. The sharks cause damage to seines and gillnets, loss of hooked or netted salmon, and damage to trolling gear.

Salmon sharks are potentially dangerous to humans, although there are no positively documented attacks. Unsubstantiated reports of attacks by this species are likely due to misidentification of more aggressive species, such as great whites.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (bites or stings)

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Life Cycle

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Like other species in the family Lamnidae, only the right ovary of salmon sharks is functional. Fertilization is internal, and development proceeds within the uterus. Salmon sharks are ovoviviparous, but developing embryos maintain no direct connection to the mother to obtain nutrition. Oophagy has been observed in this species, and likely represents the primary source of nutrition for developing embryos. The pregnant female ovulates and the unfertilized eggs are sent to the nidamental gland, where they are filled with yolk. The eggs are then moved to the uterus, where the embryos can feed on them. Litters tend to contain 4 to 5 young, which are approximately 60 to 65 cm PCL at birth.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Conservation Status

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Salmon sharks are currently listed as "Data Deficient" by the IUCN Red List. Its low number of young and slow maturity may make it vulnerable to overfishing, but few fishery statistics exist for the species, and its fishery is unregulated in international waters. However, due to this lack of knowledge and the potential impact of fishing on this species' populations, heavy regulations were imposed on Alaskan sport fishing for this species in 1997.

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Behavior

provided by Animal Diversity Web

While information on intraspecific communication in salmon sharks is lacking, this species, like other cartilaginous fishes, perceives its environment using visual, olfactory, chemo- and electroreceptive, mechanical, and auditory sensory systems.

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; vibrations ; chemical ; electric

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Reproduction

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Little is known about how salmon sharks find and select mates, although seasonal migrations and aggregations of individuals likely facilitates this process. Males hold on to females by biting their pectoral fin during copulation, which consists of the insertion of one of the male's claspers (modified pelvic fins) into the female's cloaca. Couples have no further contact following copulation.

Mating System: polygynandrous (promiscuous)

Salmon sharks mate in northern waters during autumn and give birth after a 9 month gestation period, during their southern migration in late spring through early summer. Individuals that populate the central and western North Pacific are thought to breed off the coast of Honshu, Japan. Those that populate the eastern North Pacific breed off the coasts of Oregon and California. Pups are born in nursery grounds in the central North Pacific transition zone or along the coast of United States and Canada. Female salmon sharks in the western North Pacific reproduce annually, and are estimated to bear 70 offspring in their lifetime, while evidence suggests that females in the eastern North Pacific reproduce every two years.

Sexual maturity of males in the western North Pacific is estimated to occur at approximately 140 cm PCL (corresponding to an age of 5 years), and between 170 and 180 cm (ages 8 to 10 years) for females. For salmon sharks in the eastern North Pacific, sexual maturity is reached between 125 and 145 cm PCL (ages 3 to 5 years) for males and 160 to 180 cm (ages 6 to 9) for females. Salmon sharks in both regions reach maximum lengths of approximately 215 cm PCL for females and about 190cm PCL for males.

Breeding interval: Females in the eastern North Pacific breed every two years, while those in the western North Pacific breed annually.

Breeding season: Breeding occurs in autumn and winter in the northern hemisphere.

Average number of offspring: 4-5.

Average gestation period: 9 months.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 6 to 10 years.

Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 3 to 5 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (Internal ); ovoviviparous

Females provide nutrition to their embryos through unfertilized eggs, which are consumed by the developing young. Protection is provided to embryos through residence within the mother's uterus until they have fully developed and are able to fend for themselves.

Parental Investment: female parental care ; pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Female, Protecting: Female)

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Lupton, E.; A. Mendoza and B. Razavinematollahi 2012. "Lamna ditropis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Lamna_ditropis.html

- author

- Emily Lupton, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Anthony Mendoza, San Diego Mesa College

- author

- Brian Razavinematollahi, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Paul Detwiler, San Diego Mesa College

- editor

- Jeremy Wright, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Biology

provided by Arkive

Occurring singly or in schools of several individuals (3), salmon sharks are long distance, high-speed predators (2), occasionally seen at or near the surface in some areas. They can maintain their body temperature well above that of the surrounding cold water of the North Pacific, and may have the highest body temperature of any shark (3). This allows them to maintain warm swimming muscles and internal organs, so they can still hunt effectively in cool waters (2).

The salmon shark is considered to be one of the main predators of the Pacific salmon, and its voracious feeding on this fish has earned it its common name (3). However, it is an opportunistic feeder that consumes a wide variety of fish that also includes (amongst many others) herring, sardines, pollock, Alaska cod, lanternfishes and mackerel. It also feeds on some squid and is sometimes attracted to by-catch dumped back into the ocean by shrimp trawlers (3).

After spending the summer in the north of their range, the salmon shark migrates south to breed. In the western North Pacific they migrate to Japanese waters whereas in the eastern North Pacific, the salmon shark breeds off the coast of Oregon and California, USA. The young are born in spring after a gestation period of around nine months (3). The salmon shark is ovoviviparous, and oophagy (when the growing embryos eat unfertilized eggs to gain nutrients) has been recorded in this shark (4). Most litters contain between two and five young. Male salmon sharks are thought to mature at about five years and live to at least 27 years; females reach maturity at eight to ten years and are known to live to at least 20 years (3).

Conservation

provided by Arkive

In 1997, the Alaska Board of Fisheries closed all commercial shark fishing in state waters and implemented strict regulations in the state sports fishery for salmon sharks (4). Measures such as these are vital in protecting this species' future, until further research can determine the conservation status of this magnificent predator.

Description

provided by Arkive

This formidable hunter, which is sometimes mistaken for the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), can be distinguished by its shorter snout and the dusky blotches that mark the white abdomen of adults (3) (4). The rest of the salmon shark's stocky, spindle-shaped body is dark bluish-grey or blackish, with white blotches around the base of the pectoral fins. The first dorsal fin is large, while the second dorsal and anal fins are tiny and are able to pivot. Its crescent-shaped tail gives it impressive propulsion through the water (2) (3), while its large, well-developed eyes enable it to spot potential prey (2), and its large, blade-like teeth are well suited to gripping slippery fish (2) (3).

Habitat

provided by Arkive

This species is a coastal and oceanic shark, inhabiting waters between 2.5 and 24 degrees Celsius, generally from the surface down to depths around 152 metres, although one individual has been recorded at 255 metres (3).

Range

provided by Arkive

The salmon shark occurs in the North Pacific Ocean. From Japan, North Korea, South Korea and the Pacific coast of Russia, its distribution extends east to the Pacific coast of the U.S.A., Canada, and probably Mexico (3).

Status

provided by Arkive

Classified as Data Deficient (DD) on the IUCN Red List (1).

Threats

provided by Arkive

The salmon shark is often caught as by-catch in Japanese, United States and Canadian fisheries. When caught, often just the fins are taken for shark fin soup and the rest is discarded, although sometimes the flesh may be sold for consumption in Japan and the United States (4). Many fishermen view salmon sharks as pests, as they often damage fishing gear, making them more likely to be killed if captured (4). In addition to the threat of by-catch, some recreational fishing for this shark occurs in Alaskan and Canadian waters (4), and some commercial fishing has taken place in the past, such as in Prince William Sound, Alaska (5). However, the lack of population and catch data for the salmon shark means that its status, and the impact these activities may be having on the species, cannot be assessed and thus the IUCN has classified it as Data Deficient (1).

Habitat

provided by EOL authors

Salmon sharks can be found patrolling nearshore waters as they search for prey. However, they spend much of the year in the open ocean, often at great depths. During the summer, salmon sharks hunt near the thermocline, an area in the water column where there is an abrupt change in water temperatures.

Brief Summary

provided by EOL authors

Salmon sharks (Lamna ditropis) are fish, in the Lamnidae family of sharks. This family includes the great white and mako sharks. Lamnidae sharks are warm-blooded (partially endothermic) and salmon sharks are the warmest of the Lamnidaes, as warm as 20ºF (7ºC) warmer than the waters in which they swim.

Size

provided by EOL authors

Salmon sharks can grow to about 12 feet (3.7 m) and weigh over 1000 pounds (454 kg). Females are slightly larger than males.

Life Expectancy

provided by EOL authors

Most fish are aged using bony structures called otoliths; however, sharks do not have bones, making it difficult to age them. A recent discovery has found that the snout of the salmon shark is ossified, or bone. What appear to be annual rings in the snout’s bone indicate that a 6½-foot (2-m), 300-pound (136- kg) female salmon shark is about ten or eleven years old. From this information, researchers estimate that salmon sharks may live 25 years or more.

Reproduction

provided by EOL authors

Male salmon sharks become sexually mature at about five years and females at about eight to 12 years. Breeding takes place during the fall. Salmon sharks are ovoviviparous meaning that they produce eggs that hatch within the female’s body. During gestation the young sharks attack and consume non-developing eggs. This is common among sharks. The female, therefore, gives birth to two to five live young, called pups. The estimated gestation period is around nine months to a year. Young are 32–34 inches (81–86 cm) long at birth and are fully equipped with sharp senses and sharp teeth, the better to take prey and avoid predators.

Behavior

provided by EOL authors

Salmon sharks feed together on schools of salmon and other fish and may work together to herd the prey. The sharks appear to be non-aggressive towards each other as they feed. During breeding, males will bite on to females to hold on. What appears to us to be dangerous and aggressive behavior seems to work for sharks. The sharks seem to not be troubled by pain.

Distribution

provided by EOL authors

Salmon sharks can be found in nearshore and offshore waters of the North Pacific Ocean, from Baja California to the Bering Sea and west to Russia, Korea and Japan.

General Ecology

provided by EOL authors

Salmon sharks move into areas of high food abundance, or “hot spots.” They consume the schools of fish until the amount of prey is reduced or dispersed. Then the sharks move on to the next patch of food. Salmon sharks have learned where and when these hot spots occur. This behavior may result in salmon sharks intercepting salmon runs but they take far less than the number of fish harvested by fishermen. An interesting thing about salmon shark predation in Alaskan waters is that it may afford some stability to the ecosystem. Mathematical models show that if a predator-control program removed these sharks from the ecosystem some marine species populations would decline. Scientists think it would work like this: If the sharks were removed, several fish species numbers would increase, especially arrowtooth flounder. The increased flounder population would remove smaller forage fish such as capelin and herring, which reduces the food supply for other fish, seabirds and marine mammals. Some marine mammal populations in the Gulf of Alaska are already at critically low numbers, so further declines would have a devastating effect on the ecosystem and likely would force more fishing restrictions to protect the food of the marine mammals. The complexities of the predator–prey relationship and their effects on the marine ecosystem are difficult and next-to-impossible to predict and manage. A precautionary approach to fisheries and predator management is the wisest choice.

Management

provided by EOL authors

Japanese scientists estimate more than 2,000,000 salmon sharks hunt the North Pacific Ocean, but this estimate is controversial and may be high. Their population appears to be healthy in Alaska. However, salmon sharks are a long-lived, slow-growing species with a low reproductive rate. This makes them susceptible to over-exploitation. Fisheries on sharks would likely result in a dramatic decline in the regional shark population, similar to what has occurred to other shark populations in other oceans. Alaska fisheries managers are taking a conservative management approach to shark fisheries. This probably has helped in maintaining healthy shark populations in Alaska and also a relatively stable marine ecosystem. The Alaska fisheries managers have not addressed as yet the many fishermen in the region who regularly kill any sharks they catch by cutting off their tails or shooting them on sight and bycatch of sharks in the Bering Sea.

Threats

provided by EOL authors

Other sharks may prey upon salmon sharks and they are sometimes taken by orcas. It is not known if the transient type and/or resident type orcas are taking the sharks. Some commercial salmon fishermen regularly kill salmon sharks, and there is an active and growing sport fishery in Alaska for salmon sharks.

Trophic Strategy

provided by EOL authors

Salmon sharks are opportunistic feeders. They consume a wide variety of prey including salmon, squid, rockfish, pollock, herring, capelin, sablefish, mackerel, sculpin, tomcod, daggerteeth, lantern fishes, pomfret, shrimp, lancet fish, spiny dogfish sharks, arrowtooth flounder and sea otters. PREDATORY CHARACTERISTICS: Salmon sharks are equipped with good vision and sense of smell to aid in locating and attacking prey. Another well-developed sense is their ability to detect weak electromagnetic fields that are emitted by the muscles of swimming fish and other prey. Sharks have a number of large pores, or channels, in their snouts that are used to detect these weak electrical fields. Sharks’ “sixth sense” is so acute as to allow them to track their prey by following the wake the prey leaves in the water. Muscles work more efficiently when warm. Most fish lose their internal heat to the surrounding water. A salmon shark’s warm-bloodedness is achieved by countercurrent heat exchange in which heat produced by internal muscle activity is used to warm the oxygenated blood returning from the gills. Salmon sharks benefit from warm-bloodedness and more efficient muscles by being able to reach higher swimming speeds. Salmon sharks also are equipped with several rows of moderately large, smooth-edged teeth. These are used to grasp and tear their prey into bite-sized pieces. Much of the salmon shark’s prey is taken in deep water. However, some salmon sharks will move into shallow bays and the mouths of salmon streams to pursue salmon that are preparing to spawn. The sharks concentrate their efforts in these hot spots, and as many as 1,000 salmon sharks per square mile (386 salmon sharks per km2) have been observed in these areas. The sharks will hunt the salmon in groups, or packs, similar to how wolves hunt their prey. Salmon are attacked from below or behind. Salmon sharks have been seen leaping out of the water in pursuit of their prey and may clear the water with a salmon in their jaws. At least two accounts of salmon sharks taking sea otters were reported in Prince William Sound, Alaska. In one account the 300–400 pound (136–181 kg) shark attacked a female otter as her pup swam nearby. The shark grabbed the sea otter and shook, tearing the otter to pieces only ten feet (3 m) from a fishing boat. Otter blood was splattered across the boat’s stern and onto the fishermen. The pup sea otter escaped, but likely died of starvation or was preyed upon by bald eagles, which are on the lookout for unattended young otters. I'm still not convinced these were not great white sharks taking the sea otters. Salmon sharks are considered dangerous because of their large size and aggressive nature. However, they are rarely aggressive towards people, and there is only one account of a salmon shark attacking and biting a person.

Migration

provided by EOL authors

Satellite tags attached to salmon shark dorsal fins have revealed that in the summer some sharks migrate to near-shore waters in pursuit of prey. They tend to use deeper and more offshore waters after salmon spawning ends in October. Salmon sharks are highly migratory and may move thousands of miles (>10,000 km) each year in search of prey. Some of the salmon sharks in Prince William Sound, Alaska stay in these waters year round and feed on the large schools of herring. In Russia, salmon sharks are called herring sharks.

Functional Adaptations

provided by EOL authors

COLOR: Salmon sharks are dark gray to nearly black above. The underside is whitish with gray blotches. The shark’s colorations help camouflage it both from above and below. SPEED: Salmon sharks are well adapted to travel swiftly through the water. Their bodies are stocky with a pointed or conical snout. Salmon sharks use their large, powerful tail to propel them through the water. Another adaptation for speed is their rough skin. The skin holds water, creating a water-to-water low-resistance interface. When doing submarine research, the U.S. Navy became interested in how salmon sharks could travel so fast in water. Navy researchers reported clocking salmon sharks at over 50 miles per hour (80 km/hr), which puts them among the fastest of fish. PREDATORY CHARACTERISTICS: Salmon sharks are equipped with good vision and sense of smell to aid in locating and attacking prey. Another well-developed sense is their ability to detect weak electromagnetic fields that are emitted by the muscles of swimming fish and other prey. Sharks have a number of large pores, or channels, in their snouts that are used to detect these weak electrical fields. Sharks’ “sixth sense” is so acute as to allow them to track their prey by following the wake the prey leaves in the water. Muscles work more efficiently when warm. Most fish lose their internal heat to the surrounding water. A salmon shark’s warm-bloodedness is achieved by countercurrent heat exchange in which heat produced by internal muscle activity is used to warm the oxygenated blood returning from the gills. Salmon sharks benefit from warm-bloodedness and more efficient muscles by being able to reach higher swimming speeds. Salmon sharks also are equipped with several rows of moderately large, smooth-edged teeth. These are used to grasp and tear their prey into bite-sized pieces.

Taxonomical classification

provided by EOL authors

The taxonomical classification of the salmon shark is below:

Kingdom Animalia

Subkingdom Eumetazoa

(Unranked) Bilateria

Superphylum Deurostomia

Phylum Chordata

(Unranked) Craniata

Subphylum Vertebrata

Superclass Gnathostomata

Class Chondrichthyes

Order Lamniformes

Family Lamnidae

Genus Lamna

Lamna ditropis

Benefits

provided by FAO species catalogs

This species has been fished in the North Pacific in the past by Japanese coastal and oceanic longliners. Salmon sharks are commonly caught by Japanese, United States and Canadian offshore salmon gill netters as bycatch but are generally discarded (except for fins). They are also caught in salmon seines, by salmon trollers towing hooks, and possibly by bottomtrawlers off Alaska; Russian research vessels have regularly caught them in pelagic trawls in the western North Pacific. They are occasionally trammel-netted by halibut fishermen off California and have showed up in numbers as bycatch in gillnets set for swordfish and threshers off California but have usually not been marketed there. Sports anglers in Alaska and Canada catch salmon sharks using rod and reel much like porbeagle anglers in the North Atlantic. The flesh of the salmon shark is used fresh for human consumption in Japan, where it is processed into various fish products, and to a lesser extent in Alaska and California, United States, where it is seldom marketed and has in the past (California) been occasionally sold as swordfish. Presumably its flesh is less desirable than that of the shortfin mako. Its oil, skin (for leather), and fins (for shark fin soup) are utilized also. The heart of the salmon shark is highly appreciated in a local sashimi dish in the northern fishing port of Kesennuma, where most of the landings of salmon sharks occur in Japan (R. Bonfil, pers. comm.). Salmon sharks are generally considered a nuisance for the damage they do to salmon nets and other fishing gear. A commercial fishery was initiated off Alaska but this did not succeed. FAO catch statistics for recent salmon shark landings were not available (FAO FishStat Plus database, 2000) but available data (Makihara, 1980) indicates that Japanese fishers landed 100 to 41 000 t during 1952-1978 (with one very high catch year, 41 000 t in 1954, but mostly below 10 000 t and averaging about 6 900 t). Bycatch of salmon sharks in the flying squid and large-mesh driftnet fisheries of the North Pacific in 1990, just before high-seas driftnets were internationally banned was estimated to be about 5 400 t and 71 t respectively. Recently (1997) there has been numerous strandings of small salmon sharks, ca. 1 m long, off north-central and southern California (R. Lea, pers. comm.), which was of rare occurrence in the 1970s and 1980s. Whether this has to do with human-induced environmental problems such as pollution or unusual water conditions is not known. Conservation Status : The conservation status of this species is of concern because it is heavily fished as largely discarded but complementary bycatch (with finning) in major pelagic fisheries in the North Pacific. Unlike Lamna nasus, this species has limited fisheries statistics (with no country reporting catch statistics to FAO in 1997) and no regulation of the largely pelagic fishery in international waters, so that trends in abundance are unknown. It also has a negative image as an abundant and low-value pest that avidly eats or damages valuable salmon and wrecks gear, which encourages fishers to kill it and add to mortality from finning and capture trauma. Knowledge of its biology is limited despite its abundance, which invites neglect, but its fecundity is very low and probably cannot sustain current fishing pressure for extended periods.

- bibliographic citation

- Sharks of the world An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Volume 2 Bullhead, mackerel and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). Leonard J.V. Compagno 2001. FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes. No. 1, Vol. 2. Rome, FAO. 2001. p.269.

- author

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN

Brief Summary

provided by FAO species catalogs

Habitat: A common coastal-littoral, offshore and epipelagic shark with a preference for boreal to cool temperate waters, found at depths from the surface to below 152 m. One was photographed at 255 m near the bottom in Monterey Canyon using an underwater camera, while a diver in a submersible saw one at 224 m off Alaska. Salmon sharks are common in continental offshore waters but range inshore to just off beaches; they also are abundant far from land in the North Pacific Ocean basin, along with their pelagic fish prey. Salmon sharks are common and are often encountered by oceanic and coastal fisheries but are sketchily known biologically. Behaviour and sociobiology are little-known. They occur singly and in schools or feeding aggregations of several individuals and in some areas are seen at or near the surface.Water temperatures where salmon sharks were caught ranged from 2.5° to 24°C. They are swift-swimming sharks, maintaining a body temperature well above ambient water temperature. Recent studies suggest that salmon sharks may have the highest body temperature of any shark. Body temperature elevations of 8° to 11°C above that of the surrounding water have been reported for smaller specimens, while elevations up to 13.6°C have been recorded in larger ones (Smith and Rhodes 1983; Goldman and Human, in press).Salmon sharks are migratory, with segregation by size and sex, and with larger sharks ranging more northerly than young. In the western North Pacific large sharks migrate from Japanese waters (where they breed) in the wintertime, move north to the Sea of Okhotsk and the western Bering Sea when the water warms, and return to Japan in the autumn or early winter (for a one-way distance of 3 220 km). In the eastern Pacific females apparently migrate south to pup in the spring off Oregon and California, USA, as suggested by commercial fish catch records, washed up (beached) young of the year and anecdotal information. A strong sexual segregation appears to exist across the Pacific Ocean basin, with males dominating the western North Pacific and females dominating the eastern North Pacific (K.J. Goldman and J. A. Musick, pers. comm.). This shark reproduces by aplacental viviparity, with uterine cannibalism (oophagy); litter size is 2 to 5 young. Length of gestation period might be nine months; length of entire reproductive cycle unknown. Breeding occurs in late summer and into autumn, and females bear young in spring. Breeding and nursery areas may be localized in the offshore western North Pacific between about 156° and 180°E in the open ocean, off the southern Kuril region, and in the Sea of Okhotsk, where young below 60 cm (possibly newborn) occur and juveniles up to 110 to 120 cm long also are found. Age 0 and 1 salmon sharks occur off California, USA, suggesting that a breeding and nursery ground might exist in the eastern North Pacific (K.J. Goldman and J.A. Musick, pers. comm.). Males may mature at 5 years and about 182 cm TL, and females at 8 to 10 years and about 221 cm TL (Tanaka, 1980). Females in the eastern North Pacific live to at least 20 years of age, males to at least 27 years; preliminary indications are that female salmon sharks mature at an earlier age and are heavier in the eastern North Pacific relative to those living in the western North Pacific (K.J. Goldman and J.A. Musick, pers. comm.). Salmon sharks are opportunistic feeders and eat a variety of pelagic and demersal bony fishes including Pacific salmon and steelhead trout (Salmonidae), herring and sardines (Clupeidae), pollock, Alaska cod and tomcod (Gadidae), lancetfishes (Alepisauridae), daggerteeth (Anotopteridae), sauries (Scombresocidae), lanternfishes (Myctophidae), pomfrets (Stromateidae), mackerel (Scomber, Scombridae), lumpfishes (Cyclopteridae), sculpins (Cottidae), possibly rockfish (Sebastes, Scorpaenidae), possibly sablefish (Anoplopomatidae), and Atka mackerel (Pleurogrammus, Hexagrammidae). Salmon sharks also feed on spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias, Squalidae) and several species of pelagic squid, and have been attracted to bycatch offal dumped by shrimp trawlers. The salmon shark is generally considered to be one of the principal predators of Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus) apart from humans and is depicted as voraciously feeding on salmon. This is apparently the case around the Aleutians and the Gulf of Alaska, where peaks in abundance in salmon sharks follow maximum catches of salmon and the distribution and migrations of the two appear to be strongly correlated as predator and prey. Salmon sharks caught by Japanese pelagic salmon gill netters in this area have had salmon in their stomachs and little else. However Blagoderov (1994) suggested that this relationship is highly unlikely, and cited major differences in areal distribution between salmon and salmon sharks in the western North Pacific, with most salmon sharks concentrated south of the main migration path of salmon and very few within it. In the western North Pacific these sharks congregate in areas with breeding aggregations of herring and sardines and may be selecting these fishes rather than salmon.

- bibliographic citation

- Sharks of the world An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Volume 2 Bullhead, mackerel and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). Leonard J.V. Compagno 2001. FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes. No. 1, Vol. 2. Rome, FAO. 2001. p.269.

- author

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN

Size

provided by FAO species catalogs

Maximum total length about 305 cm; anecdotal accounts mention sizes of 3.7 to 4.3 m TL but cannot be confirmed, and confusion with the larger white shark is possible and has happened. Size at birth between 40 and 50 cm and 85 cm TL, with the largest foetuses at least 70 cm long and the smallest free-ranging young between 40 and 50 cm. Males maturing at about 182 cm TL (5 years) and females at about 221 cm TL (8 to 10 years); both sexes adult over about 210 to 220 cm TL.

- bibliographic citation

- Sharks of the world An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Volume 2 Bullhead, mackerel and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). Leonard J.V. Compagno 2001. FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes. No. 1, Vol. 2. Rome, FAO. 2001. p.269.

- author

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN

Distribution

provided by FAO species catalogs

Coastal and oceanic. North Pacific: Japan (including Sea of Japan), North Korea, South Korea, and the Pacific coast of Russia (including Sea of Okhotsk) to Bering Sea and the eastern Pacific coast of the USAand Canada (Alaska south to British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and southern California) and probably Mexico (northern Baja California).

- bibliographic citation

- Sharks of the world An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Volume 2 Bullhead, mackerel and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). Leonard J.V. Compagno 2001. FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes. No. 1, Vol. 2. Rome, FAO. 2001. p.269.

- author

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN

Diagnostic Description

provided by FAO species catalogs

fieldmarks: Heavy spindle-shaped body, short conical snout, moderately large blade-like teeth with lateral cusplets, long gill slits, large first dorsal fin with dark free rear tip, minute, pivoting second dorsal and anal fins, strong keels on caudal peduncle, short secondary keels on caudal base, crescentic caudal fin, underside of preoral snout dark, often dusky blotches on ventral surface of body and white patches over pectoral bases. Snout short and bluntly pointed, with preoral length 4.5 to 7.6% of total length (adults 4.5 to 5.0%), space from eye to first gill slit 1.3 to 1.9 times preorbital length. First upper lateral teeth with oblique cusps. Total vertebral count 170, precaudal vertebral count 103. Cranial rostrum expanded as a huge hypercalcified knob which engulfs most of the rostral cartilages except bases in adults. Colour:Dark grey or blackish on dorsolateral surface of body, white below, with white abdominal colour extending anteriorly over pectoral bases as a broad wedge-shaped band; first dorsal fin without a white free rear tip; ventral surface of head dusky and abdomen with dusky blotches in adults but not in young.

- Applegate et al., 1989

- Blagoderov, 1994

- Bonfil, 1994

- Brodeur, 1988

- Goldman & Human, (in press).

- H. Mollet, (pers. comm.)

- Hubbs & Follett, 1947

- K.G. Goldman & J. A. Musick, (pers. comm.)

- Larkins, 1964

- Makihara, 1980

- Nagasawa, 1998

- Nakaya, 19711984

- Paust, 1987

- Paust & Smith, 1986

- R. Lea, (pers. comm.)

- S. Kato, (pers. comm.)

- Sano, 1962

- Smith & Rhodes, 1983

- Strasburg, 1958

- T. Neal, (pers. comm.)

- Tanaka, 1980

- Urquhart, 1981

- bibliographic citation

- Sharks of the world An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Volume 2 Bullhead, mackerel and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). Leonard J.V. Compagno 2001. FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes. No. 1, Vol. 2. Rome, FAO. 2001. p.269.

- author

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN

Trophic Strategy

provided by Fishbase

A carnivore (Ref. 9137).

Morphology

provided by Fishbase

Dorsal spines (total): 0; Dorsal soft rays (total): 0; Analspines: 0; Analsoft rays: 0

- Recorder

- Cristina V. Garilao

Migration

provided by Fishbase

Oceanodromous. Migrating within oceans typically between spawning and different feeding areas, as tunas do. Migrations should be cyclical and predictable and cover more than 100 km.

- Recorder

- Kent E. Carpenter

Life Cycle

provided by Fishbase

Exhibit ovoviparity (aplacental viviparity), with embryos feeding on other ova produced by the mother (oophagy) after the yolk sac is absorbed (Ref. 50449). Litter size is up to 4 young (Ref. 247). Distinct pairing with embrace (Ref. 205).

Diagnostic Description

provided by Fishbase

First dorsal fin uniformly dark, no light rear tip; ventral surface of body white with dusky blotches (Ref. 247).

- Recorder

- Cristina V. Garilao

Biology

provided by Fishbase

A coastal-littoral and epipelagic shark that prefers boreal to cool temperate waters, from the surface to at least 152 m, and is common in continental offshore waters but range inshore to just off beaches. Occurs singly or in schools or feeding aggregations of several individuals; feeds on fishes (Ref. 247). Seasonally migratory (following food prey) and segregate by age and sex where adults move further north than young (Ref. 58085). Ovoviviparous, embryos feeding on yolk sac and other ova produced by the mother (Ref. 50449). With up to 4 young in a litter (Ref. 247). Fast swimmer (Ref. 9988). Potentially dangerous but has never or seldom been implicated in human attacks (Ref. 247). Causes considerable damage to commercial catches and gear (Ref. 6885). Utilized fresh, dried or salted, and frozen; fins, hides and livers are also used, with fins having particular value; can be broiled and baked (Ref. 9988). Reported to attain at least 27 years of age and reach maximum depth of at least 792 m (in Ref. 119696).

- Recorder

- Kent E. Carpenter

Importance

provided by Fishbase

fisheries: minor commercial; gamefish: yes; price category: unknown; price reliability:

- Recorder

- Kent E. Carpenter

Salmon shark

provided by wikipedia EN

The salmon shark (Lamna ditropis) is a species of mackerel shark found in the northern Pacific ocean. As an apex predator, the salmon shark feeds on salmon, squid, sablefish, and herring.[2] It is known for its ability to maintain stomach temperature (homeothermy),[3] which is unusual among fish. This shark has not been demonstrated to maintain a constant body temperature. It is also known for an unexplained variability in the sex ratio between eastern and western populations in the northern Pacific.[4]

Description

Jaws and some vertebrae of a salmon shark

Adult salmon sharks are medium grey to black over most of the body, with a white underside with darker blotches. Juveniles are similar in appearance, but generally lack blotches. The snout is short and cone-shaped, and the overall appearance is similar to a small great white shark. The eyes are positioned well forward, enabling binocular vision to accurately locate prey.[5]

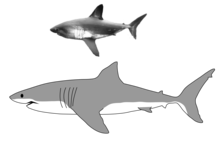

Comparison of the size of a salmon shark (top) and its relative the great white shark (bottom)

The salmon shark generally grows to between 200 and 260 cm (6.6–8.6 ft) in length and weighs up to 220 kg (485 lb).[6] Males appear to reach a maximum size slightly smaller than females. Unconfirmed reports exist of salmon sharks reaching as much as 4.3 m (14.2 ft); however, the largest confirmed reports indicate a maximum total length of about 3.0 m (10 ft).[4] The claims of maximum reported weight over 450 kg (992 lb) are "unsubstantiated".[4][6]

Biology

Reproduction

The salmon shark is ovoviviparous, with a litter size of two to six pups.[7] As with other Lamniformes shark species, the salmon shark is oophagous, with embryos feeding on the ova produced by the mother.

Females reach sexual maturity at eight to ten years, while males generally mature by age five.[8] Reproduction timing is not well understood, but is believed to be on a two-year cycle with mating occurring in the late summer or early autumn.[4] Gestation is around nine months. Some reports indicate the sex ratio at birth may be 2.2 males per female, but the prevalence of this is not known.[4]

Homeothermy

As with only a few other species of fish, salmon sharks have the ability to regulate their body temperature.[3] This is accomplished by vascular counter-current heat exchangers, known as retia mirabilia, Latin for "wonderful nets". Arteries and veins are in extremely close proximity to each other, resulting in heat exchange. Cold blood coming from the gills to the body is warmed by blood coming from the body. This results in blood coming from the body losing its heat so that by the time it interacts with cold water from the gills, it is about the same temperature, so no heat is lost from the body to the water. Blood coming towards the body regains its heat, allowing the shark to maintain its body temperature. This minimizes heat lost to the environment, allowing salmon sharks to thrive in cold waters.

Their homeothermy may also rely on SERCA2 and ryanodine receptor 2 protein expression, which may have a cardioprotective effect.[9]

Range and distribution

It is common in continental offshore waters, but ranges from inshore to just off beaches. It occurs singly, in feeding aggregations of several individuals, or in schools. Tagging has revealed a range which includes sub-Arctic to subtropical waters.[9]

The salmon shark occurs in the North Pacific Ocean, in both coastal waters and the open ocean. It is believed to range as far south as the Sea of Japan and as far north as 65°N in Alaska and in particular in Prince William Sound during the annual salmon run. Individuals have been observed diving as deep as 668 m (2,192 ft),[10] but they are believed to spend most of their time in epipelagic waters.

Regional differences

Age and sex composition differences have been observed between populations in the eastern and western North Pacific. Eastern populations are dominated by females, while the western populations are predominantly male.[6] Whether these distinctions stem from genetically distinct stocks, or if the segregation occurs as part of their growth and development, is not known. The population differences may be a result of Japanese fishermen harvesting the male population. Japanese herbalists use the fins of males as ingredients in many traditional medicines said to treat various forms of cancer.[11]

Human interactions

Currently, no commercial fishery for salmon shark exists, but they are occasionally caught as bycatch in commercial salmon gillnet fisheries, where they are usually discarded. Commercial fisheries regard salmon sharks as nuisances since they can damage fishing gear[7] and consume portions of the commercial catch. Fishermen deliberately injuring salmon sharks have been reported.[12]

Sport fishermen fish for salmon sharks in Alaska.[13] Alaskan fishing regulations limit the catch of salmon sharks to two per person per year. Sport fishermen are allowed one salmon shark per day from April 1 to March 31 in British Columbia.[14]

The flesh of the fish is used for human consumption, and in the Japanese city of Kesennuma, Miyagi, the heart is considered a delicacy for use in sashimi.[7]

Although salmon sharks are thought to be capable of injuring humans, few, if any, attacks on humans have been reported, but reports of divers encountering salmon sharks and salmon sharks bumping fishing vessels have been given.[12] These reports, however, may need positive identification of the shark species involved.

Declines in the abundance of economically important king salmon in the 2000s may be attributed to increased predation by salmon sharks, based on remote temperature readings from tagged salmon that indicate they have been swallowed by sharks.[15]

See also

References

-

^ Rigby, C.L.; Barreto, R.; Carlson, J.; Fernando, D.; Fordham, S.; Francis, M.P.; Herman, K.; Jabado, R.W.; Liu, K.M.; Marshall, A.; Romanov, E. (2019). "Lamna ditropis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T39342A124402990. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T39342A124402990.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

-

^ Hulbert, Leland B.; Rice, J. Stanley (December 2002). "Salmon Shark, Lamna ditropis, Movements, Diet and Abundance in the Eastern North Pacific Ocean and Prince William Sound, Alaska". Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Restoration Project 02396.

-

^ a b Goldman, Kenneth; Anderson, Scot; Latour, Robert; Musick, John A. (2004). "Homeothermy in adult salmon sharks, Lamna ditropis". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 71 (4): 403–411. doi:10.1007/s10641-004-6588-9. S2CID 37474646.

-

^ a b c d e Goldman, Kenneth (August 2002). "Aspects of Age, Growth, Demographics, and Thermal Biology of Two Lamniform Shark Species". PhD Dissertation, College of William and Mary, School of Marine Science.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) -

^ "Salmon shark".

-

^ a b c Goldman, Kenneth; Musick, John A. (2006). "Growth and maturity of salmon sharks (Lamna ditropis) in the eastern and western North Pacific, and comments on back-calculation methods". Fishery Bulletin. 104 (2): 278–292.

-

^ a b c Compagno, Leonard (2001). Sharks of the World, Vol. 2. Rome, Italy: FAO.

-

^ Nagasawa, Kazuya (1998). "Predation by Salmon Sharks (Lamna distropis) on Pacific Salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) in the North Pacific Ocean". Bulletin of the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission. 1: 419–432.

-

^ a b Weng, Kevin C.; Pedro C. Castilho; Jeffery M. Morrissette; Ana M. Landeira-Fernandez; David B. Holts; Robert J. Schallert; Kenneth J. Goldman; Barbara A. Block (2005). "Satellite Tagging and Cardiac Physiology Reveal Niche Expansion in Salmon Sharks" (PDF). Science. 310 (5745): 104–106. Bibcode:2005Sci...310..104W. doi:10.1126/science.1114616. PMID 16210538. S2CID 9927451.

-

^ Hulbert, Leland B.; Aires-da-Silva, Alexandre M.; Gallucci, Vincent F.; Rice, J. Stanley (2005). "Seasonal foarging movements and migratory patterns of female Lamna ditropis tagged in Prince William Sound, Alaska". Journal of Fish Biology. 67 (2): 490–509. doi:10.1111/j.0022-1112.2005.00757.x.

-

^ "Traditional medicines continue to thrive globally - CNN.com".

-

^ a b "Biology of the Salmon Shark". Reefquest Center for Shark Research. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

-

^ "Fishing for Salmon Shark in Alaska". Fish Alaska Magazine. Archived from the original on 2006-10-21. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

-

^ "Refresh".

-

^ Jim Paulin (17 July 2016). "Salmon sharks might play a role in king salmon declines". Anchorage Daily News.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Salmon shark: Brief Summary

provided by wikipedia EN

The salmon shark (Lamna ditropis) is a species of mackerel shark found in the northern Pacific ocean. As an apex predator, the salmon shark feeds on salmon, squid, sablefish, and herring. It is known for its ability to maintain stomach temperature (homeothermy), which is unusual among fish. This shark has not been demonstrated to maintain a constant body temperature. It is also known for an unexplained variability in the sex ratio between eastern and western populations in the northern Pacific.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors