en

names in breadcrumbs

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Koppotiges of inkvisse (Cephalopoda) is 'n klas seediere wat tot die orde van weekdiere (Mollusca) behoort. Hierdie klas sluit inkvisse en seekatte in.

Die inkvisse, seekatte en nautili, wat almal deel uitmaak van die klas Cephalopoda (koppotiges), is ’n hoogs ontwikkelde groep see weekdiere (phylum Mollusca). In baie opsigte kan hulle as die mees gevorderde groep lewende ongewerwelde diere beskou word. Die klas word deur slegs 130 lewende genera en 650 spesies verteenwoordig en dit lyk of die groep stadig maar seker minder word omdat sowat 10000 fossiel-spesies bekend is.

Die grootste lewende ongewerwelde dier, die reuse-pylinkvis (Arehiteuthis), behoort tot hierdie groep. Hierdie dier kan 20 m lank word (insluitende die tentakels). Die kleinste koppotige dier, die inkvis Idiosepius, is skaars 2,5 cm lank. Hoewel die koppotige diere deel van die phylum Mollusca (weekdiere) uitmaak, toon hulle heelwat afwykinge van die algemene beeld van hierdie groep. In teenstelling met die stereotipe beeld van weekdiere as diere wat stadig voortbeweeg, is die koppotige diere vinnig bewegende roofdiere wat hoofsaaklik in die diepsee lewe.

Nog ’n afwyking is die dier se goed ontwikkelde oë en hoë intelligensie. Met die uitsondering van die nautili het die koppotige diere geen uitwendige skulp nie. Die Koppotiges gebruik hulle 8 of 10 suierdraende arms om voedsel mee te vang. Die nautilus het egter sowat 90 tentakels. Uniek by die koppotige diere is die "bek” om die mondopening. Met hierdie papegaaiagtige chitienbek word stukke kos afgebyt. Die inkvisse, seekatte en hul verwante behoort tot die phylum Mollusca (weekdiere). Omdat hierdie diere se arms direk aan hul kappe vasgeheg is, word hulle die koppotiges (Cephalopoda) genoem. Die grootste en intelligentste ongewerwelde diere behoort tot hierdie klas. Omdat die koppotige diere in groot getalle voorkom, vorm hulle een van die grootste potensiële voedselbronne van die see. Die diere word in baie wêrelddele geëet en is ook indirek vir die mens van belang omdat hulle 'n groot deel van die potvis en ander kleiner walvisse se dieet vorm.

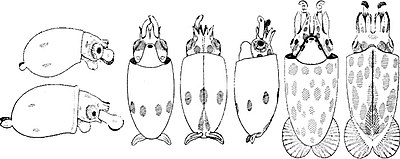

Die liggaam van die koppotige dier bestaan uit 'n kop met vangarms aan. Die liggaamsgrootte van volwasse koppotiges kan baie varieer. Die kleinste inkvis, Idiosepius, is skaars 2,5 cm lank, terwyl sommige reuse-inkvisse (die Architeuthis-spesies) tot 20 m lank kan word. Die romp van hierdie reuse-diere is sowat 6 m lank, terwyl die arms 3 tot 4 m lank kan word. Daarbenewens het die reuse-pylinkvis twee tentakels wat 14 m lank is. Hierdie tentakels is waarskynlik verantwoordelik vir die legendes van reuse-seeslange. Die meeste Koppotiges se vel kan vinnig van kleur verander vanweë die chromatofore van verskillende kleure wat in die vel aanwesig is.

Die chromatofore is stervormige epidermisselle wat kleurstof (pigment) bevat. Die selle kan vergroot en saamtrek en daardeur die kleure meer of minder opvallend maak. Dit stel die dier in staat om die kleur van sy omgewing aan te neem (skutkleur). Ook bepaalde "emosies" kan die koppotige dier van kleur laat verander. 'n Kenmerkende orgaan by alle weekdiere (Mollusca) is die voet. By die Koppotiges is dit egter gewysig tot vangarms en 'n tregter (hewel). Die tregter word gebruik vir die uitskeiding van die afval, ink en eiers. Hierdie orgaan, wat soos 'n buis by die mantelholte uitsteek, kan ook vir voortbeweging gebruik word. Die vangarms het gesteelde, gespierde en beweeglike suierplaatjies.

Sommige koppotige diere besit naas hul agt vangarms ook twee tentakels, met ander woorde 10. Op die tentakels kom die suierapparaat slegs op die breë punte voor. Soms is die horingagtige rande van die suiers gewysig tot hake. By die groter pylinkvisse kan die suiers 'n deursnee van 20 cm bereik. Tussen die vangarms lê die mond met twee horingagtige kake, in die vorm van 'n papegaai se snawel, wat gebruik word om gepantserde prooi (soos krappe) in stukke te byt. In die mond is twee paar speekselkliere en ’n raspertong (radula) met sewe klein tandjies per dwarsry. Soos in die geval van alle vleiseters is die dermkanaal kort en voorsien van ’n middel derm-spysverteringsklier. Die koppotige diere het goed ontwikkelde oë wat met die van die werweldiere vergelyk kan word. Die aanpassing (skerpstelling) van die oog geskied deur die verandering van die ooglens se posisie. By die grootste pylinkvisse kan die oog 40 cm in deursnee wees. Die dier se ewewigsin sowel as die tassin in die arms is ook goed ontwikkel. Die senuknope (ganglia) van die senustelsel is in die kop geleë en deur kopkraakbeen omhul. Die senustelsel bestaan onder meer uit 'n aantal baie groot senuselle.

Hierdie reuse-neurone speel 'n belangrike rol in neurofisiologiese navorsing. Die liggaam van die koppotige dier word omhul deur 'n mantel wat 'n aantal organe beval. Die inksak skei die ink van die inkklier deur die rektum en tregter uit. Die ink is bruinswart en bevat die pigment melanien. Vroeër is hierdie pigment as 'n kommersiële kleurstof bemark (sepia). Die koppotige diere in die diepsee skei nie ink af nie, maar skei soms 'n liggewende vloeistof af. Suurstof word deur die kieue, wat in die mantelholte geleë is, opgeneem. Die gereelde sametrekking van die mantel lei daartoe dat vars water deurentyd die mantelholte binnestroom. Die Koppotiges het 'n geslote bloedvatstelsel en blou bloed. Die blou kleur word veroorsaak deur die aanwesigheid van hemosianien, wat die asemhalingspigment is. Die dier het 2 niere. Die uitwendige skulp, wat so kenmerkend vir bykans alle weekdiere is, is by die egte pyl-inkvisse, inkvisse en seekatte afwesig. Die nautilus (subklas Nautiliodea) het egter wel 'n uitwendige skulp. Dikwels het die koppotige diere inwendige skulpe, maar soms is die skulp onontwikkel (onvolledig) of heeltemal afwesig.

Die struktuur en vorm van die inwendige skulp verskil by die verskillende inkvisse en seekatte. Die skulp van die inkvis (genus Sepia) bestaan uit kalklamelle wat dig teenmekaar Iê. By die genus Spirula bestaan die skulp uit 'n gedraaide kalkbuisie wat slegs enkele senitimeters lank is en deur tussenskotte in kamertjies (kompartemente) verdeel word. By die pylinkvisse (genus Loligo) is die skulp tot 'n horingagtige, lang slag veer of pen gereduseer en by die genus Octopus het die skulp bykans verdwyn. Die skulp van die wyfie-papiernautilus (Argonauta argo) kan anatomies nie met die skulp van ander koppotiges vergelyk word nie. Hierdie dier se skulp is gevorm uit twee van die dier se arms en funksioneer as bergplek vir die eiers.

Die Koppotiges (Cephalopoda) is roofdiere wat alleen of in groepe lewe. Vir jagdoeleindes gebruik hulle hul vangarms, tentakels, hake en 'n gifklier (wat by sommige koppotige diere aanwesig is) vir die vang van hul prooi. Tog het die eeue-oue vrees van die mens vir gevaarlike seekatte ongegrond geblyk te wees. Die koppotige diere beweeg deurdat hulle kruip, swem of deur middel van straalaandrywing voortbeweeg (hoofsaaklik laasgenoemde).

Deurdat die dier sy mantel saamtrek en verslap word 'n bewegende waterstroom veroorsaak deur die water wat in die mantelholte ingetrek word en dan weer deur die tregter uitgestoot word. Die vinnige uitstoot van 'n stroom water stel die dier in staat om vinnig vorentoe of agteruit te beweeg. Pylinkvisse het voorts ook vinne wat gebruik word vir stadige beweging of om in die water te hang. Die meeste inkvisse en seekatte is vleisetend en lewe hoolsaaklik van skaaldiere en vissies. Die pylinkvis Illex het 'n buitengewone voedselsiklus: die volwasse pylinkvisse eet klein makriele, terwyl die volwasse makriele weer klein pylinkvissies eet. Pylinkvisse het dikwels ook kannibalistiese neigings. Die seekatte eet graag tweekleppige weekdiere en tienpotige skaaldiere en kan so die kreefnywerheid groot skade berokken.

Die koppotige diere is weer op hulle beurt die prooi van dolfyne, potvisse, haaie, rogge, robbe en pikkewyne. Ter verdediging teen sy vyande kan die inkvis of seekat sy ink soos 'n rookgordyn in die water spuit of baie vinnig die kleur van sy omgewing aanneem. Die diere kan ook verbasend vinnig wegvlug. Alle koppotige diere lewe in die see, van die tropiese tot die poolseë, en word in vlak kuswaters en in die diepsee aangetref. Enkele spesies, soos die Spirula spirula en die gewone seekat (Octopus vulgaris), kom dwarsoor die wêreld voor.

By die inkvisse is die geslagte (manlik en vroulik) geskei. Die mannetjies is dikwels kleiner as die wyfies. By die genus Argonauta is die mannetjies so klein in vergelyking met die wyfie dat daar van dwergmannetjies gepraal word. Tydens paring plaas die mannetjie pakkies sperm selle (spermatofore) in die wyfie se liggaam. Hierdie handeling word met een van sy arms, die hektokotilus-arm, wat spesiaal daarvoor toegerus is, gedoen. By die Argonauta en die Tremoctopus is die arms baie gewysig en word die arm tydens paring deur die mannetjie losgelaat en in die wyfie se mantelholte gelaat. Sommige spesies van die koppotige diere vertoon broeisorg. Uit die eiers word klein koppotige diertjies gebroei wat vir 'n tydlank vryswemmend lewe.

Die koppotige diere word in twee subklasse ingedeel, naamlik die Nautiloidea (nautilus) en die Coleoidea (seekatte, pylinkvisse en inkvisse). Die Nautiloidea (nautilus) het 'n uitwendige skulp wat op een vlak gedraai is en deur inwendige tussenskotte (septa) in kompartemente verdeel is. Die hedendaagse nautilus (genus Nautilus) word in die suidwestelike deel van die Stille Oseaan gevind tot op 'n diepte van 600 m. Hulle is ook vleiseters wat hoofsaaklik van kreef lewe.

Die nautilus se skulp is uit twee lae aragoniet, 'n vorm van kalsiumkarbonaat, opgebou. Die buitenste laag is wit met bruin strepe, terwyl die binneste laag en die septa uit perlemoer bestaan. Soms word daar 'n pêrel in die skulp gevorm. Die dier se sowat 90 tentakels het geen suiers nie. Vier tentakels van die mannetjie is saamgegroei tot 'n keëlvormige orgaan, die spadiks. Hiermee plaas die mannetjie die pakkies spermselle in die wyfie se liggaam en bevrug haar. Die eiers word een vir een gele en is ongeveer 4 cm groot. Die nautilus het geen inkklier nie. Die Coleoidea se skulpe is inwendig, gereduseer of heeltemal afwesig. Die diere het gewoonlik 2 paar kieue, en 8 of 10 arms wat suiers of hake dra.

Die subklas Coleoidea word in vier ordes ingedeel, te wete die Sepioidea (inkvisse en bottelstert-pylinkvisse), die Teuthoidea (pyl-inkvisse), die Vampyromorpha en die Octopoda (seekatte). Die Sepioidea het agt vangarms en twee tentakels waarop geen suiers voorkom nie. Organismes van hierdie orde het 'n inwendige skulp en die mantel is van vinne voorsien. 'n Verteenwoordiger van hierdie orde is die Spirula spirula, wat tot die familie Spirulidae behoort en in diep water in die tropiese en subtropiese seë voorkom. Die klein dwerginkvisse behoort tot die familie Sepiolidae. Die pyl-inkvisse (familie Loliginidae) het ’n liggaam met pylvormige vinne. In die noordelike seë lewe die reuse-pylinkvis (familie Architeuthidae). In die diepsee lewe die Bathyteuthidae, wat gekenmerk word deur liggewende organe. Vlieënde inkvisse (genus Onychoteuthis) kan klein afstande bo die water sweef. Koppotige diere van die orde Octopoda het gewoonlik 8 arms. Gesteelde suiers kom op hierdie diere se arms voor. Die diere het geen uitwendige skulp nie. Tot die familie Octopodidae behoort die seekat (Octopus vulgaris).

Koppotiges of inkvisse (Cephalopoda) is 'n klas seediere wat tot die orde van weekdiere (Mollusca) behoort. Hierdie klas sluit inkvisse en seekatte in.

Die inkvisse, seekatte en nautili, wat almal deel uitmaak van die klas Cephalopoda (koppotiges), is ’n hoogs ontwikkelde groep see weekdiere (phylum Mollusca). In baie opsigte kan hulle as die mees gevorderde groep lewende ongewerwelde diere beskou word. Die klas word deur slegs 130 lewende genera en 650 spesies verteenwoordig en dit lyk of die groep stadig maar seker minder word omdat sowat 10000 fossiel-spesies bekend is.

Die grootste lewende ongewerwelde dier, die reuse-pylinkvis (Arehiteuthis), behoort tot hierdie groep. Hierdie dier kan 20 m lank word (insluitende die tentakels). Die kleinste koppotige dier, die inkvis Idiosepius, is skaars 2,5 cm lank. Hoewel die koppotige diere deel van die phylum Mollusca (weekdiere) uitmaak, toon hulle heelwat afwykinge van die algemene beeld van hierdie groep. In teenstelling met die stereotipe beeld van weekdiere as diere wat stadig voortbeweeg, is die koppotige diere vinnig bewegende roofdiere wat hoofsaaklik in die diepsee lewe.

Nog ’n afwyking is die dier se goed ontwikkelde oë en hoë intelligensie. Met die uitsondering van die nautili het die koppotige diere geen uitwendige skulp nie. Die Koppotiges gebruik hulle 8 of 10 suierdraende arms om voedsel mee te vang. Die nautilus het egter sowat 90 tentakels. Uniek by die koppotige diere is die "bek” om die mondopening. Met hierdie papegaaiagtige chitienbek word stukke kos afgebyt. Die inkvisse, seekatte en hul verwante behoort tot die phylum Mollusca (weekdiere). Omdat hierdie diere se arms direk aan hul kappe vasgeheg is, word hulle die koppotiges (Cephalopoda) genoem. Die grootste en intelligentste ongewerwelde diere behoort tot hierdie klas. Omdat die koppotige diere in groot getalle voorkom, vorm hulle een van die grootste potensiële voedselbronne van die see. Die diere word in baie wêrelddele geëet en is ook indirek vir die mens van belang omdat hulle 'n groot deel van die potvis en ander kleiner walvisse se dieet vorm.

Los cefalópodos (Cephalopoda, del griegu κεφαλή (kephalé), "cabeza" y ποδός (podós), "pie" → pies na cabeza) son una clase d'invertebraos marinos dientro del filu de los moluscos. Esisten unes 700 especies, comúnmente llamaos pulpos, calamares, sepias y nautilos.[1] Toos pertenecen a la subclase coleoidea, a esceición del nautilos, perteneciente a la subclase Nautilina.

Nos cefalópodos el pie carauterísticu de los moluscos apaez al pie de la cabeza, diversificáu en dellos tentáculos, dende 8 nos pulpos hasta los 90 que pueden tener los nautilos. Nésti postreru nun esisten ventoses nos tentáculos.

Dalgunos d'estos tentáculos (en coloideos) modificáronse n'estructures reproductives llamaes espádices que cumplen el rol d'introducir espermatóforos (sacos llenos d'espelma) nel cuévanu paleal de la fema. La concha tiende a amenorgase, faese interna o sumir, según la especie. Cuando tienen una concha bien desenvuelta, ta estremada en cámares separaes por septos y l'animal habita la última cámara (la más recién). Nos coloideos, cuando esiste, ye interna y estrémase en 3 zones; dende la rexón caudal a la cefálica estes son cara, fragmocono (tabicado) y proóstraco, cada unu con desenvolvimientu variable en cada grupu. En nautiloideos ye esterna, planoespiral y tabicada na so totalidá.

Les xibies o sepias, al pie de los nautilos, siguen el mesmu sistema natatoriu que los sos antepasaos, enllenando de gas ciertes partes de la so concha pa llexar. Los calamares naden per mediu de la flotación dinámica, similar a los tiburones, con una propulsión a reacción d'agua bien afinada. El restu de cefalópodos que viven alloñaos de la superficie desenvolvieron un sistema químicu de flotación, enllenando de compuestos amoniacales o aceites los espacios del so cuerpu; al ser éstes sustances menos trupes que l'agua, llexen.

Los cefalópodos tienen célules pigmentaries sobre'l mantu llamaes cromatóforos. Diches célules tienen pigmentos que s'espanden o entiesten a voluntá per mediu d'una contraición muscular controlada pol sistema nerviosu. D'esta manera pueden camudar de color en cuestión de segundos pa mimetizarse col espaciu circundante y pasar desapercibíos. Tamién usen esta capacidá pa comunicase ente ellos per mediu de la so coloración y gracies a la so aguda visión.

Tienen un complexu sistema nerviosu, con unos ganglios alredor del esófagu que formen un auténticu celebru. El celebru alcuéntrase estremáu en dos porciones, llamaes masa supraesofágica y masa subesofágica según la so posición respeuto al esófagu, anque dambes partes tán xuníes por conectivos. Una traza particular y esclusivo de los cefalópodos ye que'l celebru alcuéntrase arrodiáu por una masa o caxa cartilaxinosa nun intentu evolutivu de formar un craniu. Munchos cefalópodos tienen comportamientos de fuxida rápidos que dependen d'un sistema de fibres nervioses motores xigantes que controlen les contraiciones potentes sincróniques de los músculos del mantu, lo que dexa la salida a presión de l'agua del cuévanu paleal. El centru de coordinación d'esti sistema ye un par de neurones xigantes de primer orde (formaes pola fusión de ganglios viscerales) que dan a neurones xigantes de segundu orde, y estes estiéndense hasta un par de grandes ganglios estrellaos. D'estos ganglios estrellaos unes neurones xigantes de tercer orde inervan les fibres musculares circulares del mantu. Neurólogos de tol mundu esperimentaron con pulpos a lo llargo del sieglu XX y detectóse nellos una intelixencia cimera a cualesquier otru invertebráu; son capaces d'atopar la salida d'un llaberintu, abrir botes ya inclusive aprender comportamientos de los sos conxéneres.

El güeyu de los cefalópodos ye un órganu análogu al de los vertebraos, de distintu orixe evolutivu y embrionariu, pero per converxencia dambos son bien paecíos. Los cefalópodos tienen el güeyu más desenvueltu de tolos invertebraos ya inclusive anden a la tema col de los vertebraos.

Tienen un cuerpu musculoso y flexible, propiedá que s'intensifica nos pulpos, que son capaces d'escondese n'espacios 10 vegaes más pequeños qu'el so cuerpu.

Tienen oyíu a baxes frecuencies, como los mamíferos marinos, que-yos dexa alcontrar a los sos depredadores más allá del so campu visual.

Segreguen un líquidu corito, la tinta, cola qu'enturbien l'agua con oxetu de despintase. La tinta ye un pigmentu que s'almacena na bolsa de la tinta asitiada enriba del rectu y puede ser espulsáu al traviés del sifón.

Nel metabolismu d'esti grupu ye destacable la importancia del llogru d'enerxía a partir de la metabolización de proteínes, lo que nun ye una gran ventaya evolutiva frente a otros grupos de la so redolada como los pexes, qu'aferruñen les grases del so texíu adiposo. Aun así esto paez ser ye una de les carauterístiques que-yos dexó conquistar hábitats tan esclusivos como son les grandes fondures, onde a exemplares de gran tamañu son predados por calderones, zifios y cachalotes. Tamién esta carauterística metabólica ta rellacionada coles propiedaes nutritives cuando ye d'esti grupu ye utilizáu n'alimentación humano: so conteníu graso, altu conteníu proteico, y n'ocasiones sabor amoniacal pola presencia de bases nitrogenadas, restos de la mentada metabolización proteica.

Los cefalópodos #dixebrar del restu de los moluscos fai alredor de 500 millones d'años (Cámbricu Mediu), cola apaición de los primeros moluscos capaces d'enllenar ciertes partes de la so concha de gas pa llexar. Ésta nueva capacidá natatoria, qu'entá anguaño caltienen delles especies, dexó-yos abandonar el fondu marín al que taben amestaos los moluscos y aportar a nueves rutes trófiques más superficiales.[1]

Los últimos descubrimientos indiquen que los cefalópodos aniciáronse abondo antes de lo que se pensaba hasta agora.[2]

Pero éstos primeros cefalópodos, d'hábitat entá próximu a la mariña, fueron movíos al interior del mar por organismos más avanzaos, tales como pexes y reptiles marinos. Otru problema plantegábase-yos: la so vida superficial torgába-yos baxar demasiáu al fondu marín una y bones la so concha nun soportaba la presión de l'agua. Los descendientes con conches más pequeñes podíen baxar más y tener más posibilidaes alimenticies polo que la seleición natural quedos e con aquéllos con concha pequeña, llegando ésta a faese interna o sumir. Aprosimao 470 millones d'años antes de l'actualidá (Ordovícicu Mediu) yá había coleoideos, al pie de una gran gama de cefalópodos escastaos na actualidá.[cita riquida]

Según la teoría del meteoritu cayíu na península de Yucatán fai 65 millones d'años (Cretácicu Cimeru), nesi tiempu la tierra sufrió graves cambeos climáticos que causaron estinciones masives, como la de los dinosaurios. Dichu meteoritu tamién pudo ser causante de la estinción de la mayor parte de los cefalópodos, como los amonites. Tan solo sobrevivieron los coleoideos y los nautiloideos. Por eso dizse que los cefalópodos actuales provienen d'un auténticu llinaxe de supervivientes. Anque agora sían alimentu básico de miles d'especies, nel so momentu tuvieron no más alto de les cadenes trófiques marines.

Na actualidá sobreviven unes 700 especies, anque el so númberu amóntase cada añu, quedando entá delles especies vives por afayar. Aparte envalórase que'l númberu d'especies estinguíes ronda les 11.000.[cita [ensin referencies]

Subclase Nautiloidea

Subclase Ammonoidea † - amonites

Subclase Coleoidea

Los cefalópodos son unu de los mariscos más apreciaos. Cómense solos (calamares a la romana, sepia a #planchar, topeto, pulpu a la gallega, etc.) o como ingredientes d'otros platos (paella de mariscu, fideuá, etc.)

Los cefalópodos (Cephalopoda, del griegu κεφαλή (kephalé), "cabeza" y ποδός (podós), "pie" → pies na cabeza) son una clase d'invertebraos marinos dientro del filu de los moluscos. Esisten unes 700 especies, comúnmente llamaos pulpos, calamares, sepias y nautilos. Toos pertenecen a la subclase coleoidea, a esceición del nautilos, perteneciente a la subclase Nautilina.

Başıayaqlılar, sefalopodlar (lat. Cephalopoda yun. Κεφαλόποδα — başıayaqlılar) — molyusklar tipinə aid sinif.

Bu sinfin nümayəndələrinin ayaqları başlarında yerləşən bir neçə qolcuğa və hərəkəti təmin edən qıfa çevrilmişdir. Qolcuqlarda çoxlu sormaclar vardır. Suda aktiv üzürlər. Yırtıcıdırlar. Çox az nümayəndəsində çanaq vardır.

Sinfin müasir nümayəndələri iki yarımsinfə bölünürlər:

Başıayaqlılar, sefalopodlar (lat. Cephalopoda yun. Κεφαλόποδα — başıayaqlılar) — molyusklar tipinə aid sinif.

Bu sinfin nümayəndələrinin ayaqları başlarında yerləşən bir neçə qolcuğa və hərəkəti təmin edən qıfa çevrilmişdir. Qolcuqlarda çoxlu sormaclar vardır. Suda aktiv üzürlər. Yırtıcıdırlar. Çox az nümayəndəsində çanaq vardır.

Els cefalòpodes (Cephalopoda; Grec plural Κεφαλόποδα (kephalópoda); que significa "cap-peu") són una classe de mol·luscs que es caracteritzen per presentar simetria corporal bilateral, un cap prominent i un conjunt de braços o tentacles modificats a partir del peu de mol·lusc primitiu. Tenen el cap gran rodejat de tentacles, la boca, quitinosa, que es troba entre tots aquests, té forma de bec. També tenen ràdula. Els cefalòpodes es troben als oceans de tot el món i a totes les fondàries. L'estudi dels cefalòpodes és una branca de la malacologia anomenada teutologia.

En els cefalòpodes el peu característic dels mol·luscs apareix junt amb el cap, diversificat en diversos tentàcles, des dels vuit del pop fins als 90 que pot arribar a tenir el nàutil. En aquest últim, el cefalòpode vivent més primitiu, els tentacles encara no estan proveïts de ventoses.

Els cefalòpodes es defensen amb la tinta o mascara que fabriquen i amb la capacitat de camuflar-se.

Els cefalòpodes van ser un grup dominant durant el període Ordovicià, representats pels primitius nautiloïdeus. Avui en dia la classe conté dos, emparentats llunyanament, subclasses: els coleoïdeus, que inclouen els pops, els calamars, i les sèpies; i els nautiloïdeus, representats per Nautilus i Allonautilus. En els coleoïdeus, la conquilla de mol·lusc s'ha interioritzat o és absent, mentre que en els nautiloïdeus, la conquilla externa encara es conserva. Es coneixen unes 800 espècies de cefalòpodes. Dos tàxons (subclasses) extints importants són els ammonoïdeus i els belemnoïdeus.

Algunes de les formes primitives de cefalòpodes eren enormes, amb closques que arribaven a mesurar diversos metres de longitud. La closca tendí a reduir-se, internar-se o desaparèixer, segons l'espècie. Quan tenen una conquilla ben desenvolupada, està dividida en septes i l'animal habita en el septe més jove.

Es coneixen unes 800 espècies de cefalòpodes,[1] tot i que contínuament es descriuen noves espècies. S'han descrit uns 11.000 tàxons extints, tot i que la naturalesa de cos tou dels cefalòpodes implica que no són de fàcil fossilització.

Els cefalòpodes es troben a tots els oceans de la Terra. Cap d'ells pot sobreviure en aigua dolça, però l'espècie Lolliguncula brevis, que es troba a la badia de Chesapeake, pot ser una notable excepció en tant que tolera l'aigua salobre.[2]

Els cefalòpodes ocupen la major part de la profunditat de l'oceà, des de les planes abissals fins a la superfície del mar. La seva diversitat és major a prop de l'equador (unes 40 espècies recuperades en xarxes a 11°N en un estudi de diversitat) i decreix cap als pols (unes 5 espècies capturades a 60°N).[3]

Actualment hi les següents subclasses i ordres.

Els cefalòpodes (Cephalopoda; Grec plural Κεφαλόποδα (kephalópoda); que significa "cap-peu") són una classe de mol·luscs que es caracteritzen per presentar simetria corporal bilateral, un cap prominent i un conjunt de braços o tentacles modificats a partir del peu de mol·lusc primitiu. Tenen el cap gran rodejat de tentacles, la boca, quitinosa, que es troba entre tots aquests, té forma de bec. També tenen ràdula. Els cefalòpodes es troben als oceans de tot el món i a totes les fondàries. L'estudi dels cefalòpodes és una branca de la malacologia anomenada teutologia.

En els cefalòpodes el peu característic dels mol·luscs apareix junt amb el cap, diversificat en diversos tentàcles, des dels vuit del pop fins als 90 que pot arribar a tenir el nàutil. En aquest últim, el cefalòpode vivent més primitiu, els tentacles encara no estan proveïts de ventoses.

Els cefalòpodes es defensen amb la tinta o mascara que fabriquen i amb la capacitat de camuflar-se.

Els cefalòpodes van ser un grup dominant durant el període Ordovicià, representats pels primitius nautiloïdeus. Avui en dia la classe conté dos, emparentats llunyanament, subclasses: els coleoïdeus, que inclouen els pops, els calamars, i les sèpies; i els nautiloïdeus, representats per Nautilus i Allonautilus. En els coleoïdeus, la conquilla de mol·lusc s'ha interioritzat o és absent, mentre que en els nautiloïdeus, la conquilla externa encara es conserva. Es coneixen unes 800 espècies de cefalòpodes. Dos tàxons (subclasses) extints importants són els ammonoïdeus i els belemnoïdeus.

Algunes de les formes primitives de cefalòpodes eren enormes, amb closques que arribaven a mesurar diversos metres de longitud. La closca tendí a reduir-se, internar-se o desaparèixer, segons l'espècie. Quan tenen una conquilla ben desenvolupada, està dividida en septes i l'animal habita en el septe més jove.

Hlavonožci (Cephalopoda) jsou nejdokonalejší třída měkkýšů. Všichni jsou aktivní mořští dravci. Patří mezi ně starobylá loděnka, inteligentní chobotnice, sépie, obří krakatice a další. Dnes žijící hlavonožci se dělí na skupiny čtyřžábří (loděnka) a dvoužábří (chobotnice, oliheň, …)

Hlavonožci měří od jednoho centimetru do mnoha metrů (i přes 20 m). Mají dvoustranně souměrné tělo a chapadla. Chapadel je u jednoduchých druhů, jako je loděnka, okolo 30 až 90 a jsou krátké. Vyspělé druhy jich mají méně, zato jsou delší a mají přísavky. Decapodiformes (desetiramenatci) mají 8 kratších chapadel a 2 delší a Octopodiformes (chobotnice) mají 8 stejně dlouhých. Chobotnice mohou přijít o několik chapadel, která jim znovu dorostou. Pohybují se třemi způsoby, buď pomocí vlnění ploutevního lemu nebo chapadel nebo vytlačování vody ze sifonu. Tento tryskovitý pohyb umožňuje některým menším druhům vyskakovat nad hladinu. Dýchají žábrami. V případě ohrožení vypouštějí hlavonožci inkoustový oblak, který je skryje a mohou tak nepozorovaně uplavat. Je buď černý nebo hnědý.

Dříve měli všichni hlavonožci svou schránku, dnes ji má jen málo zástupců, např. loděnka. Schránka se ve vývoji začala přemisťovat dovnitř těla. Sépie má sépiovou kost, další desetiramenatci jen tzv. meč a chobotnice nemají vůbec nic. Jejich mozek je však obvykle krytý chrupavčitou schránkou, která jej chrání před poškozením.

Hlavonožci měří od jednoho centimetru do mnoha metrů (i přes 20 m). Podle současných znalostí je největším hlavonožcem kalmar Hamiltonův a nikoli krakatice obrovská.[1] U měření velikosti desetiramenných hlavonožců je zásadní problém, který rozměr považovat při srovnání za rozhodující. Délka osmi ramen se obvykle blíží délce samotného těla, ale i zde jsou rozdíly. Dvě dlouhá chapadla s rozšířenými konci však daleko přesahují věnec ramen a mohou být velmi dlouhá. Krakatice nalezená roku 1887 na Novém Zélandu měla při celkové délce 17,35 m tělo bez ramen dlouhé pouhých 2,35 m. Celých 15 m připadlo na chapadla.

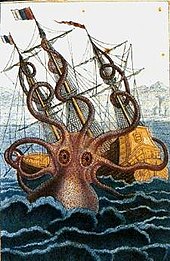

Tvrzení, že není možné, aby bezobratlí byli větší než obratlovci, dříve ztěžovalo vědcům obhajovat existenci obrovských hlavonožců. Jedním z nich byl na počátku 19. století francouzský vědec Pierre Denys de Monfort. Rozdělil obří hlavonožce na dvě skupiny, krakeny a kolosální chobotnice. Krakeni se měli vyskytovat v severských mořích, plavali volně a byli méně nebezpeční než kolosální chobotnice, které žily u dna tropických moří a byly podle něho zodpovědné za většinu útoků na plachetnice. Ačkoli si přesnou hmotnost těchto obřích hlavonožců netroufl odhadnout, tušil, že bude větší než hmotnost největších velryb. Tehdy ho však nikdo neuznal a dožil v bídě a zapomnění, přestože důkazy ležely v muzeích a byly každoročně vyplavovány na břeh.

Jedním z prvních vcelku kladně přijatých svědectví byla zpráva posádky lodi Alecton, která narazila 30. 11. 1861 nedaleko ostrova Tenerife na poraněnou krakatici ležící na hladině a pokusila se několikametrového hlavonožce o hmotnosti přes 2 tuny ulovit. Protože harpuny a střely z pušek nedokázaly v měkkém těle živočicha způsobit větší poranění, nechal kapitán na tělo krakatice navléct smyčku lana. Ta se při pokusu vytáhnout zvíře na palubu zadrhla u ocasní ploutve. Hmotnost zvedaného těla byla nakonec taková, že lano ploutev odřízlo a zmrzačená krakatice zmizela v mořských hlubinách.

Jako by se poté roztrhl s krakaticemi pytel. Na břehy vyplavala obrovská bledá těla mrtvých krakenů, nicméně pravě tehdy se s nimi příliš dobře nezacházelo. Zapsány byly obvykle jen rozměry, které se vědcům zdály příliš přemrštěné na to, aby mohly být pravdivé. Tak se nakonec největší uznávanou krakaticí stal exemplář vyplavený na pláž Timble Tickle při odlivu v listopadu 1878. Šťastný rybář se k němu však nezachoval příliš dobře. Zarazil do jeho těla kotvu, aby neuplaval a podával je jako krmení psům…

Mnoho důkazů přinášejí také možná jediní přirození nepřátelé velkých hlavonožců – vorvani. Staří velrybáři mnohokrát popisovali, jak harpunovaný vorvaň vyvrhoval kusy chapadel dodnes nevídaných rozměrů. Zatím největší takto zaznamenaný údaj hovoří o celém ramenu dlouhém 13,70 m a silném 75 cm. Vzhledem k tloušťce nemohlo jít o chapadlo a protože délka ramen zhruba odpovídá délce těla, muselo pocházet z krakatice s tělem dlouhým kolem 14 m. Druhým zdrojem informací o kořisti vorvaňů je jejich kůže. Jizvy po přísavkách krakatic často vypovídají o tom, že ulovený vorvaň svedl boj s protivníky mnohem většími než jsou mrtví hlavonožci vyplavení na plážích. A při velikosti největších krakatic je otázkou, zda vorvaň odkázaný na zásobu kyslíku v krvi a plicích vyjde ze souboje vždy jako vítěz.

Obyvatelé ostrova Andros na Bahamách jsou přesvědčení o existenci obří chobotnice, které říkají luska. Podle některých dovede uchvacovat i lidi stojící na břehu. Během druhé světové války byla v moři u východního pobřeží ostrova cvičena pod vedením Bruce Wrighta britská komanda žabích mužů. Základna však byla kvůli velkým záhadným ztrátám nakonec přesunuta jinam. Bruce Wright v roce 1967 otiskl v časopisu Atlantic Advocate názor, že luska je obří dosud neznámá chobotnice.[1]

Systematickým výzkumem oceánů jsou stále objevovány nové druhy:

Počet vymřelých hlavonožců je však mnohonásobně vyšší, odhadem více než 11 000 druhů.[5]

Hlavní smysl hlavonožců je zrak. Dokonalé komorové oči dvoužábrých hlavonožců mají podobnou stavbu jako oči savčí, oproti nim však mají obrácené uspořádání vrstev sítnice (světločivné buňky na povrchu, jejich nervy a cévní zásobení až za nimi), takže nemají slepou skvrnu (vizte obrázek vpravo). Kromě toho jsou oči obřích chobotnic největší v celé živočišné říši, průměr některých je až 40 cm.

Starobylá loděnka má však štěrbinové oči, které jsou naplněné vodou. Má sítnici, ale ne čočku.[6]

Na ramenech mají smyslová čidla hmatu a chuti, vnímají slanost, kyselost a hořkost. Dále mají statokinetická čidla polohy a pohybu.

Hlavonožci jsou obvykle samotáři, jen část olihní žije v hejnech, žádné opravdu sociální druhy však nejsou známy. Žijí velmi krátce a většinou uhynou po páření. Tyto věci by obyčejně vyloučily inteligenci, nicméně hlavonožci, zvláště chobotnice, inteligentní jsou.

Jejich nervová soustava je nejdokonalejší ze všech bezobratlých, podobně jako smysly. Jejich komorové oči jsou vyvinutější více, než savčí. Barvu pokožky mohou měnit nejen kvůli maskování, ale také kvůli komunikaci. Kromě toho vyjadřují zbarvením pokožky své emoce.

Inteligence hlavonožců se vyvíjela v důsledku jejich konkurence, obratlovců. Chobotnice jsou nejinteligentnější, sépie a olihně také vykazují známky inteligence. Přesto prvohorní zástupci, kteří vládli tehdejším mořím, nejspíše příliš inteligentní nebyli, podobně jako loděnka, která je dnes „živoucí zkamenělinou“, památkou na vyhynulé druhy.

Chobotnice dovedou měnit při lovu své strategie podle druhu kořisti a podmínek, ke kterým patří útoky na kraby, otevírání lastur atd. Staví si jednoduchá obydlí z nejrůznějších materiálů někdy i s vchodem, který mohou v případě hrozícího nebezpečí zatarasit. Využívají skalních jeskyní a přizpůsobují se při stavbě podmínkám. Do svého obydlí si nosí nejrůznější lesklé předměty, podobně jako někteří ptáci. Chobotnice si hrají. Možná se mohou učit napodobováním, což je u samotářů přinejmenším podivné.

V zajetí byly pozorovány, jak otevírají zašroubované láhve s potravou a řeší další podobně složité úkoly. Rakouský etolog Hans Fricke sledoval chobotnici, která dokázala manipulovat s průhlednými přepážkami oddělujícími jednotlivé části akvária.

Dále umí rozlišovat mezi různými geometrickými tělesy, ale také stejnými, s odlišným povrchem; také rozpozná nepatrné koncentrace látek ve vodě. Mohou si vytvořit podmíněné reakce na určité podněty. Když se v potravě objeví určitý předmět spojený s tím, že chobotnice dostane elektrošok, příště se potravy s tímto předmětem nedotkne.

Inteligenci chobotnic srovnávají různí vědci s různě vyspělými savci. Někdo ji dává na roveň hlodavcům, někdo ji srovnává i s delfíny.

Mají přímý vývin. Obvykle po páření hynou. Samec hektokotylovým chapadlem přenese spermie k samici a následně obvykle uhyne. Samice se ještě stará o vajíčka, a protože nepřijímá potravu, krátce po jejich vylíhnutí hyne.

V roce 2005 bylo poprvé zaznamenáno, že krakatice Gonatus onyx se stará o svá vajíčka.[7]

Argonaut se vyznačuje dlouhým hektokotylovým ramenem, které používá k přenosu spermií. Toto rameno se během páření odděluje a je schopné volného pohybu v moři a žije ještě dlouho uvnitř samice. (To zmýlilo i francouzského přírodovědce Cuviera, který je popsal jako cizopasného červa pod jménem Hectocotylus (se stem přísavek)). Na rozdíl od mnoha jiných hlavonožců se samice argonautů mohou pářit vícekrát, zatímco samec jen jednou.[8]

Hlavonožci jsou oblíbenou pochoutkou ve středomořských oblastech, v Japonsku i jinde na světě.

Chobotnice jsou často používány při pokusech.

Hlavonožci (Cephalopoda) jsou nejdokonalejší třída měkkýšů. Všichni jsou aktivní mořští dravci. Patří mezi ně starobylá loděnka, inteligentní chobotnice, sépie, obří krakatice a další. Dnes žijící hlavonožci se dělí na skupiny čtyřžábří (loděnka) a dvoužábří (chobotnice, oliheň, …)

Hlavonožci měří od jednoho centimetru do mnoha metrů (i přes 20 m). Mají dvoustranně souměrné tělo a chapadla. Chapadel je u jednoduchých druhů, jako je loděnka, okolo 30 až 90 a jsou krátké. Vyspělé druhy jich mají méně, zato jsou delší a mají přísavky. Decapodiformes (desetiramenatci) mají 8 kratších chapadel a 2 delší a Octopodiformes (chobotnice) mají 8 stejně dlouhých. Chobotnice mohou přijít o několik chapadel, která jim znovu dorostou. Pohybují se třemi způsoby, buď pomocí vlnění ploutevního lemu nebo chapadel nebo vytlačování vody ze sifonu. Tento tryskovitý pohyb umožňuje některým menším druhům vyskakovat nad hladinu. Dýchají žábrami. V případě ohrožení vypouštějí hlavonožci inkoustový oblak, který je skryje a mohou tak nepozorovaně uplavat. Je buď černý nebo hnědý.

Blæksprutter (Cephalopoda) er en gruppe af marine bløddyr. Det er rovdyr, der omkring munden har et større antal fangarme til at gribe byttet. I tilfælde af fare kan mange arter udspy en mørk, blækagtig væske.

Nogle få primitive arter bærer en ydre skal (nautiler), mens de fleste har en indre skal (ægte blæksprutter), der ofte er uforkalket. De ægte blæksputter deles i ottearmede og tiarmede blæksprutter. Vættelys er forstenede blæksprutter.

Der er kendt omkring 800 nulevende arter og beskrevet langt over 10.000 uddøde taksa ud fra fossiler.[1][2] Blæksprutter findes i alle dybder og er udbredt i alle verdens have, dog med flest arter omkring ækvator.

Blæksprutter (Cephalopoda) er en klasse i rækken bløddyr (Mollusca). De nulevende blæksprutter inddeles i to underklasser:[3]

Velodona togata, en art blandt de tiarmede blæksprutter.

Et par sepiablæksprutter (Sepia officinalis) på lavt vand.

Blæksprutter (Cephalopoda) er en gruppe af marine bløddyr. Det er rovdyr, der omkring munden har et større antal fangarme til at gribe byttet. I tilfælde af fare kan mange arter udspy en mørk, blækagtig væske.

Nogle få primitive arter bærer en ydre skal (nautiler), mens de fleste har en indre skal (ægte blæksprutter), der ofte er uforkalket. De ægte blæksputter deles i ottearmede og tiarmede blæksprutter. Vættelys er forstenede blæksprutter.

Die zoologische Klasse der Kopffüßer (Cephalopoda, von altgriechisch κεφαλή kephalē „Kopf“ und ποδ- pod- „Fuß“) ist eine Tiergruppe, die zu den Weichtieren (Mollusca) gehört und nur im Meer vorkommt. Es gibt sowohl pelagische (freischwimmende) als auch benthische (am Boden lebende) Arten. Derzeit sind etwa 30.000 ausgestorbene und 1.000 heute lebende Arten bekannt.[1] Zu den Kopffüßern gehören die größten lebenden Weichtiere. Der größte bisher gefundene Riesenkalmar war 13 Meter lang. Die ausgestorbenen Ammoniten erreichten eine Gehäusegröße von bis zu zwei Metern.

Der Name „Cephalopoda“ wurde 1797 von Georges Cuvier eingeführt und ersetzte die ältere, von antiken Autoren wie Aristoteles und Plinius überlieferte Bezeichnung „Polypen“ (πολύπους polýpous „Vielfüßer“), die Réaumur 1742 auf die Nesseltiere übertragen hatte und die in der modernen Zoologie ausschließlich in dieser Bedeutung gebraucht wird.

Kopffüßer besitzen einen Körper, der aus einem Rumpfteil (mit Eingeweidesack), einem Kopfteil mit anhängenden Armen und einem auf der Bauchseite gelegenen taschenförmigen Mantel besteht. Die Orientierung der Körpergliederung entspricht dabei nicht der bevorzugten Fortbewegungsrichtung. Der vordere Teil des Fußes ist bei Kopffüßern zum Trichter und zu acht, zehn oder über 90 Fangarmen (Tentakeln) entwickelt. Der Hohlraum des Mantels, die so genannte Mantelhöhle, birgt meist zwei (bei den Nautiloidea: vier) Kiemen und mündet durch ein Rohr (Hyponom oder Trichter genannt) nach außen. Der Mund ist von streckbaren Fangarmen (Tentakeln) umgeben. Am Mund befindet sich bei rezenten Arten ein papageienartiger Schnabel mit Ober- und Unterkiefer sowie eine Raspelzunge (Radula).

Die ursprünglicheren Arten, wie die Nautiloiden und die ausgestorbenen Ammoniten, sind außenschalig: Ein kalkiges Gehäuse aus Aragonit gibt ihnen als Außenskelett Schutz und Halt. Die Schale dieses Gehäuses ist dreischichtig. Unter dem äußeren Periostracum, dem Schalenhäutchen aus dem Glykoprotein Conchin, liegt die äußere Prismenschicht (Ostracum) aus prismatischem Aragonit. Die innere Schicht, das Hypostracum, besteht wie die Septen aus Perlmutt.

Die Gehäuse sind in die eigentliche Wohnkammer und einen Abschnitt mit gasgefüllten Kammern (Phragmokon) unterteilt. Mit Hilfe dieses gasgefüllten Teils kann das Gehäuse in der Wassersäule schwebend gehalten werden. Der heutige Nautilus (Perlboot) kann das Gehäuse aber nicht zum Auf- und Abstieg in der Wassersäule benutzen, da jeweils zu wenig Wasser in das Gehäuse hinein oder herausgepumpt werden kann (etwa fünf Gramm), sondern er bewegt sich mit Hilfe des Rückstoßprinzips des Trichters fort (auch senkrecht in der Wassersäule). Bei den ausgestorbenen Ammoniten wird neuerdings aber diskutiert, ob bei dieser Gruppe nicht doch ein Auf- und Abstieg in der Wassersäule durch Veränderung des Gas- bzw. Wasservolumens in den Kammern möglich war. Allerdings sind die Internstrukturen der Gehäuse von Nautiloidea und Ammonoidea auch sehr verschieden.

Die außenschaligen Kopffüßer sind nur noch durch die fünf oder sechs Arten der Gattung Nautilus repräsentiert. Eine Art wird von manchen Forschern auch als Vertreter einer eigenen Gattung (Allonautilus) aufgefasst. Aus dem Fossilbericht sind über 10.000 Arten von ausgestorbenen Nautiloideen (Perlboot-Artige) beschrieben worden. Die Zahl der ausgestorbenen Ammoniten ist bisher noch nicht exakt erfasst worden, dürfte jedoch in der Größenordnung von etwa 30.000–40.000 liegen.

Bei den innenschaligen Kopffüßern sind die Hartteile vom Mantel umschlossen:

Kalmare und Kraken haben zum Teil alternative Auftriebssysteme entwickelt (Ammoniak, ölige Substanzen etc.). In den heutigen Meeren dominieren die innenschaligen Kopffüßer (Coleoidea oder auch Dibranchiata).

Das Nervensystem der Cephalopoden ist das leistungsfähigste sowohl unter den Weichtieren als auch unter allen wirbellosen Tieren.[1] Dies gilt insbesondere für die modernen Kopffüßer (Coleoidea), bei denen die großen Nervenknoten (Cerebralganglien, Pedalganglien, Pleuralganglien) zu einer komplexen Struktur verschmolzen sind, die als Gehirn bezeichnet werden kann. Das Nervensystem der zehnarmigen Tintenfische (Decabrachia) zeichnet sich zudem durch Riesen-Axone aus, deren Übertragungsgeschwindigkeit an die Axone von Wirbeltieren heranreicht. Experimente mit abgetrennten Krakenarmen zeigten, dass die Arme über eigene, autonom agierende Nervenzentren verfügen, durch die bestimmte Reflexe, zum Beispiel bei der Nahrungssuche bzw. Jagd, unabhängig vom Gehirn ausgelöst werden können.[2] Die paarigen, seitlich am Kopf sitzenden Augen funktionieren bei den Nautiliden nach dem Lochkameraprinzip. Moderne Kopffüßer haben everse (mit lichtzugewandten Photorezeptoren in der Netzhaut ausgestattete) und ontogenetisch eingestülpte Linsenaugen analog zu den inversen (mit lichtabgewandten Photorezeptoren in der Netzhaut ausgestattete) und ontogenetisch ausgestülpten Linsenaugen der Wirbeltiere, was ein klassisches Beispiel für konvergente Evolution darstellt. Zur schnellen Verarbeitung der optischen Reize besitzt das Kopffüßergehirn große optische Loben.

Weiterhin besitzen Kopffüßer hochentwickelte Statozysten, die seitlich des Gehirns liegen und neben Gravitation und Beschleunigung auch relativ niedrigfrequenten Schall[3][4] wahrnehmen können.

Kopffüßer gelten als die intelligentesten wirbellosen Tiere.[5][6][7][8][9] Aus Verhaltensexperimenten geht hervor, dass die kognitiven Fähigkeiten von Kraken teilweise an die von Hunden heranreichen.[1][10][11] So sind sie zur Abstraktion (beispielsweise Zählen bis 4 oder Unterscheiden verschiedener Formen[1]) und zum Lösen komplexer Probleme (u. a. das Öffnen des Schraubverschlusses eines Glases, um an den Inhalt zu gelangen) in der Lage.

Als aktive Räuber verlassen sich Kopffüßer vor allem auf die Fortbewegung nach dem Rückstoßprinzip. Hierbei wird der Zwischenraum zwischen Kopf und Mantelwand, und dadurch auch das Volumen der Mantelhöhle, bei den meisten Vertretern durch das Zusammenziehen der Ringmuskeln des Mantels verringert. Infolge des entstehenden Überdruckes in der Mantelhöhle wird das Wasser durch den Trichter nach außen gezwungen, was bewirkt, dass sich der Körper in die entgegengesetzte Richtung bewegt. Durch Verändern der Stellung des Trichters kann die Fortbewegungsrichtung variiert werden. Die Seitenflossen dienen bei Kalmaren der Stabilisierung und bei Sepien, deren Seitenflossen einen großen Teil des Mantels säumen, dem „Schweben“ und Antrieb durch wellenartigen Flossenschlag. Oktopoden sind mit dem Meeresboden (Benthos) assoziiert und kriechen mit Hilfe ihrer Fangarme. Allerdings nutzen auch sie bei der Flucht den Rückstoßantrieb.

Kopffüßer sind die einzigen Weichtiere, die ein geschlossenes Kreislaufsystem besitzen. Das Blut wird bei Coleoiden durch zwei Kiemenherzen, die an der Basis der Kiemen sitzen, zu den Kiemen gepumpt. Dies führt zu einem hohen Blutdruck und zu einem schnellen Fließen des Blutes und ist notwendig, um die relativ hohen Stoffwechselraten der Kopffüßer zu unterstützen. An den Kiemen erfolgt die Anreicherung des Blutes mit Sauerstoff. Das nun sauerstoffreiche Blut wird durch ein systemisches Herz zum Rest des Körpers gepumpt.

Kiemen sind die primären Atmungsorgane der Kopffüßer. Eine große Kiemenoberfläche und ein sehr dünnes Gewebe (respiratorisches Epithel) der Kieme sorgen für einen effektiven Gasaustausch von sowohl Sauerstoff als auch Kohlenstoffdioxid. Da die Kiemen in der Mantelhöhle liegen, ist diese Art der Atmung an Bewegung gekoppelt. Bei Kalmaren und Oktopoden wurde ein wenn auch geringerer Teil der Atmung auf die Haut zurückgeführt.[12] Wie bei vielen Weichtieren erfolgt der Sauerstofftransport im Blut der Kopffüßer nicht durch eisenhaltige Hämoglobine (wie u. a. bei Wirbeltieren), sondern durch kupferhaltige Hämocyanine. Außerdem befinden sich Hämocyanine nicht in speziellen Zellen (wie Hämoglobine in roten Blutkörperchen), sondern liegen frei im Blutplasma vor. Sind Hämocyanine nicht mit Sauerstoff beladen, erscheinen sie durchsichtig und nehmen eine blaue Farbe an, wenn sie mit Sauerstoff binden.

Mit Ausnahme des detritusfressenden Vampirtintenfischs sind Kopffüßer aktive Räuber, die ausschließlich von tierischer Nahrung leben. Die Beute wird visuell wahrgenommen und mit den Tentakeln, welche mit Saugnäpfen ausgestattet sind, gegriffen. Bei Kalmaren sind diese Saugnäpfe mit kleinen Haken versehen. Sepien und Nautilus ernähren sich hauptsächlich von kleinen, auf dem Meeresboden lebenden Wirbellosen. Zur Beute der Kalmare gehören Fische und Garnelen, welche durch einen Biss in den Nacken paralysiert werden. Oktopoden sind nächtliche Jäger und stellen vor allem Schnecken, Krustentieren und Fischen nach. Zur wirksamen Tötung ihrer Beute besitzen Oktopoden ein lähmendes Gift, welches in die Beute injiziert wird. Nach ihrer Aufnahme mittels Papageienschnabel-artiger Kiefer (u. a. aus Chitin[13]) gelangt die Nahrung in den muskulären Verdauungstrakt. Die Nahrung wird durch peristaltische Bewegungen des Verdauungstraktes bewegt und hauptsächlich im Magen und im Blinddarm verdaut. Nach dem Passieren des Darms verlässt Unverdautes den Körper durch den Anus und gelangt beim Ausstoß des Wassers aus der Mantelhöhle durch den Trichter nach außen.

Viele Kopffüßer verfügen über ein ausgeprägtes Sexualverhalten. Zumeist gibt das Männchen nach ausgiebigem Vorspiel seine in Spermatophoren verpackten Spermien mit einem Arm, dem Hectocotylus, in die Mantelhöhle des Weibchens. Bei Papierbooten jedoch löst sich der Hectocotylus vom Männchen und schwimmt aktiv, von chemischen Botenstoffen des Weibchens angezogen (Chemotaxis), in deren Mantelhöhle. Die Eizellen des Weibchens werden beim Austreten aus dem Eileiter befruchtet und können in Trauben (Sepien, Kraken), oder in Schläuchen (Kalmare), welche eine Vielzahl von Eiern enthalten, abgelegt werden. Das Weibchen legt voluminöse und extrem dotterreiche Eier. Während der Embryonalentwicklung ernährt sich der Embryo von der gespeicherten Energie im Dotter. Weibliche Oktopoden säubern die abgelegten Eier mit ihren Tentakeln und Wasserschüben.

Die Furchung während der Embryogenese erfolgt partiell-diskoidal und führt dazu, dass der sich entwickelnde Embryo um den Dotter wächst. Dabei wird ein Teil der Dottermasse nach innen verlagert (innerer Dottersack); ein oft größerer, mit dem inneren Dottersack verbundener Teil der Dottermasse (äußerer Dottersack) verbleibt außerhalb des Embryos. Der Schlupf erfolgt, nachdem oder auch bevor der äußere Dotter aufgebraucht wurde. Der innere Dotter dient als Nahrungsreserve für die Zeit zwischen dem Schlupf und der vollständigen Umstellung auf selbstständig erbeutete Nahrung. Nach dem Schlupf kümmern sich erwachsene Kopffüßer nicht um ihre Nachkommen.

Kopffüßer besitzen besondere Hautzellen, die sogenannten Chromatophoren. Diese enthalten ein Pigment (Farbstoff) und sind von winzigen Muskeln umgeben, welche an diesen Hautzellen anhaften. Werden diese Muskeln angespannt, dehnt sich eine Chromatophorenzelle aus und ändert somit die Farbe an diesem Ort des Körpers. Das selektive Ausdehnen und Zusammenziehen von Chromatophoren ermöglicht die Veränderung der Farbe und des Musters der Haut. Dies spielt unter anderem bei Tarnung, Warnung und beim Paarungsverhalten eine wichtige Rolle. Beispielsweise lassen Sepien in Stresssituationen Farbstreifen wellenähnlich über den Körper laufen und können sich in Farbe und Muster einem Schachbrett anpassen.

Mit Hilfe von brauner oder schwarzer Tinte (bestehend aus Melanin und anderen chemischen Substanzen) können Kopffüßer ihre Fressfeinde erschrecken und täuschen. Die Tintendrüse liegt hinter dem Anus und entlässt die Tinte durch die Mantelhöhle und weiterhin durch den Trichter nach außen. Des Weiteren werden z. B. bei Sepia officinalis die vielen Schichten der Eihülle mit Tinte versehen, welche somit für die Tarnung der Embryos sorgt.

Innerhalb der Kalmare sind über 70 Gattungen mit Biolumineszenz bekannt. In mehreren Gattungen wird diese mit Hilfe von symbiotischen Bakterien erzeugt; in den anderen Gattungen jedoch durch eine Reaktion von Luciferin und Sauerstoff mit Hilfe des Enzyms Luciferase. Auf diese Weise biolumineszierende Zellen, sogenannte Photophoren, können der Tarnung und dem Paarungsverhalten (bei Tiefseeoktopoden) dienen. Außerdem können biolumineszierende Partikel mit der Tinte ausgestoßen werden.

Die Populationsgrößen und Verbreitungsgebiete vieler Kopffüßer-Arten sind in den letzten 60 Jahren deutlich gestiegen bzw. gewachsen. Studien legen nahe, dass der kurze Lebenszyklus der Kopffüßer ihnen ermöglicht, sich schnell an Umweltveränderungen anzupassen. Dies wird vermutlich durch beschleunigte Wachstumsphasen aufgrund ansteigender Meerestemperaturen im Zuge der Globalen Erwärmung beschleunigt. Weiter profitieren die Kopffüßer wohl von der Überfischung ihrer Fressfeinde und Nahrungskonkurrenten.[14]

Der Stammbaum (phylogenetisches System) der Kopffüßer ist bisher noch nicht völlig aufgeklärt. Einigermaßen sicher ist, dass die Tintenfische (Coleoidea), die Ammoniten (Ammonoidea), die Bactriten (Bactritida) und Teile der Geradhörner (hier die Unterklasse der Actinoceratoida) eine monophyletische Gruppe bilden, die auch als Neukopffüßer (Neocephalopoda) bezeichnet wird, während alle restlichen Kopffüßer als Perlboote i. w. S. (Nautiloidea i. w. S.) oder auch als Altkopffüßer (Palcephalopoda) zusammengefasst werden. Diese zweite Gruppe ist aber wahrscheinlich paraphyletisch, da mit einiger Sicherheit aus den Altkopffüßern die Neukopffüßer hervorgegangen sind.

Die Ammoniten sind im Devon aus Bactriten-ähnlichen Vorfahren entstanden. Auch die Tintenfische (Coleoidea) werden von den Bactriten abgeleitet. Die Bactriten sind daher eine para- oder polyphyletische Gruppierung, die aufgelöst werden müsste.

Die Tintenfische (Coleoidea) sind im Unterkarbon, möglicherweise schon im Unterdevon, aus Bactriten-ähnlichen Vorfahren entstanden. Innerhalb der Tintenfische stehen sich die ausgestorbenen Belemniten (Belemnoidea) auf der einen Seite und die Achtarmigen und Zehnarmigen Tintenfische auf der anderen Seite als Schwestergruppen gegenüber. Die letzteren beiden Schwestergruppen werden auch als Neutintenfische (Neocoleoidea) bezeichnet.

Die zoologische Klasse der Kopffüßer (Cephalopoda, von altgriechisch κεφαλή kephalē „Kopf“ und ποδ- pod- „Fuß“) ist eine Tiergruppe, die zu den Weichtieren (Mollusca) gehört und nur im Meer vorkommt. Es gibt sowohl pelagische (freischwimmende) als auch benthische (am Boden lebende) Arten. Derzeit sind etwa 30.000 ausgestorbene und 1.000 heute lebende Arten bekannt. Zu den Kopffüßern gehören die größten lebenden Weichtiere. Der größte bisher gefundene Riesenkalmar war 13 Meter lang. Die ausgestorbenen Ammoniten erreichten eine Gehäusegröße von bis zu zwei Metern.

Der Name „Cephalopoda“ wurde 1797 von Georges Cuvier eingeführt und ersetzte die ältere, von antiken Autoren wie Aristoteles und Plinius überlieferte Bezeichnung „Polypen“ (πολύπους polýpous „Vielfüßer“), die Réaumur 1742 auf die Nesseltiere übertragen hatte und die in der modernen Zoologie ausschließlich in dieser Bedeutung gebraucht wird.

Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar (Cephalopoda) — yuksak tuzilgan dengiz mollyuskalari sinfi. Tanasi (uz. 1 sm dan 5 m gacha) bilateral simmetriyali, odatda, tana va yirik boshboʻlimlaridan iborat. Oyogʻi voronkaga aylangan. Tanasi qalin mantiya bilan qoplangan. Ichki organlari keng mantiya boʻshligʻida joylashgan. Ogʻiz teshigi atrofida 8 yoki 10 ta paypaslagichlari (oyoqlari) boʻladi. Paypaslagichlarida bir necha qator boʻlib joylashgan juda koʻp soʻrgʻichlari bor. Koʻpchilik turlarining chigʻanogʻi evolyutsiya jarayonida reduksiyaga uchragan yoki mantiya burmalari ichida plastinka holida saqlanib qolgan. Haqiqiy chigʻanoq faqat nautilusda boʻladi. Urgʻochi argonavt chigʻanogʻi esa tuxumlarini olib yurishga moslashgan. Bosh miyasi togʻay skelet bilan qoplangan. Toʻtiqush tumshugʻiga oʻxshash egilgan bir juft jagʻlari ozigʻini ushlab turish va maydalash uchun xizmat kiladi. Qirgʻichlari va 2 juft soʻlak bezlari bor. Orqa ichagiga siyoh xaltasi yoʻli ochiladi. Bosh miyasi yirik, boshining ikki yonida yirik va yaxshi rivojlangan koʻzlari joylashgan. Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar rangini tez oʻzgartirish xususiyatiga ega (niqoblanish). Aksariyat turlarida nur taratuvchi organlari boʻladi. Qon aylanish sistemasi deyarli yopiq. Ayrim jinsli, baʼzi turlarida jinsiy dimorfizm yaxshi rivojlangan. Erkagi paypaslagichlarining oʻzgarishidan hosil boʻladigan spermatofori (gektokotil) yordamida urugʻ hujayralarini urgʻochisining mantiya boʻshligʻiga yoki urugʻ qabul qilgichiga kiritadi. Tuxumlari yirik, sariq moddasi koʻp. Tuxumdan voyaga yetgan davriga oʻxshash mollyuska chiqadi. Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar , odatda, reaktiv usudda faol harakat qiladi. Buning uchun boshining pastida joylashgan 2 ta tirqish orqali suv mantiya boʻshligʻiga kiradi; mantiya devorida muskullar kuchli qisqarganda suv voronkasi orqali kuch bilan otilib chiqib, mollyuska tanasini suradi. Koʻpchilik turlarida tanasining keyingi tomonida va ikki yonida bir juft suzgichlari boʻladi. Hozirgi Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar ning 650 ga yaqin turi okean va ochiq dengizlarda tarqalgan, 2 ta (toʻrt jabralilar, ikki jabralilar) kenja sinfga boʻlinadi. Toʻrt jabralilar eng qad. sodda tuzilgan (mas, nautilus), ikki jabralilar esa qolgan barcha hozirgi mollyuskalarni uz ichiga oladi. Pelagik va dengiz tubida hayot kechiradi. Yirtqich, bentofag va plantofag oziqlanadi. Koʻpchilik Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar goʻshti uchun ovlanadi. Ayrim turlari farmatsevtika sanoati uchun xom ashyo hisoblanadi. Dunyo boʻyicha har yili 1,63 mln. t ga yaqin Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar ovlanadi (qarang Mollyuskalar).

Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar (Cephalopoda) — yuksak tuzilgan dengiz mollyuskalari sinfi. Tanasi (uz. 1 sm dan 5 m gacha) bilateral simmetriyali, odatda, tana va yirik boshboʻlimlaridan iborat. Oyogʻi voronkaga aylangan. Tanasi qalin mantiya bilan qoplangan. Ichki organlari keng mantiya boʻshligʻida joylashgan. Ogʻiz teshigi atrofida 8 yoki 10 ta paypaslagichlari (oyoqlari) boʻladi. Paypaslagichlarida bir necha qator boʻlib joylashgan juda koʻp soʻrgʻichlari bor. Koʻpchilik turlarining chigʻanogʻi evolyutsiya jarayonida reduksiyaga uchragan yoki mantiya burmalari ichida plastinka holida saqlanib qolgan. Haqiqiy chigʻanoq faqat nautilusda boʻladi. Urgʻochi argonavt chigʻanogʻi esa tuxumlarini olib yurishga moslashgan. Bosh miyasi togʻay skelet bilan qoplangan. Toʻtiqush tumshugʻiga oʻxshash egilgan bir juft jagʻlari ozigʻini ushlab turish va maydalash uchun xizmat kiladi. Qirgʻichlari va 2 juft soʻlak bezlari bor. Orqa ichagiga siyoh xaltasi yoʻli ochiladi. Bosh miyasi yirik, boshining ikki yonida yirik va yaxshi rivojlangan koʻzlari joylashgan. Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar rangini tez oʻzgartirish xususiyatiga ega (niqoblanish). Aksariyat turlarida nur taratuvchi organlari boʻladi. Qon aylanish sistemasi deyarli yopiq. Ayrim jinsli, baʼzi turlarida jinsiy dimorfizm yaxshi rivojlangan. Erkagi paypaslagichlarining oʻzgarishidan hosil boʻladigan spermatofori (gektokotil) yordamida urugʻ hujayralarini urgʻochisining mantiya boʻshligʻiga yoki urugʻ qabul qilgichiga kiritadi. Tuxumlari yirik, sariq moddasi koʻp. Tuxumdan voyaga yetgan davriga oʻxshash mollyuska chiqadi. Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar , odatda, reaktiv usudda faol harakat qiladi. Buning uchun boshining pastida joylashgan 2 ta tirqish orqali suv mantiya boʻshligʻiga kiradi; mantiya devorida muskullar kuchli qisqarganda suv voronkasi orqali kuch bilan otilib chiqib, mollyuska tanasini suradi. Koʻpchilik turlarida tanasining keyingi tomonida va ikki yonida bir juft suzgichlari boʻladi. Hozirgi Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar ning 650 ga yaqin turi okean va ochiq dengizlarda tarqalgan, 2 ta (toʻrt jabralilar, ikki jabralilar) kenja sinfga boʻlinadi. Toʻrt jabralilar eng qad. sodda tuzilgan (mas, nautilus), ikki jabralilar esa qolgan barcha hozirgi mollyuskalarni uz ichiga oladi. Pelagik va dengiz tubida hayot kechiradi. Yirtqich, bentofag va plantofag oziqlanadi. Koʻpchilik Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar goʻshti uchun ovlanadi. Ayrim turlari farmatsevtika sanoati uchun xom ashyo hisoblanadi. Dunyo boʻyicha har yili 1,63 mln. t ga yaqin Boshoyoqli mollyuskalar ovlanadi (qarang Mollyuskalar).

Cefalopodo esas molusko di qua la korpo konsistas ye sako membrana, qua kontenas la viceri, e di qua la kapo esas garnisita ye palpili.

Cefalopodët klasa më e lartë e butakëve të detit, të cilët kanë rreth kokës zgjatime me ventuza, që i përdorin si këmbë për të lëvizur ose për të kapur ushqimin.

![]() Ky artikull në lidhje me biologjinë është i cunguar. Ndihmoni dhe ju në përmirsimin e tij.

Ky artikull në lidhje me biologjinë është i cunguar. Ndihmoni dhe ju në përmirsimin e tij.

Glavonošci (lat. Cephalopoda) su mehkušci koje karakterizira bilateralna simetrija i kod kojih se od stopala obrazuju ručice i mišićni lijevak. Većina ima reducirane ili sasvim zakržljale ljušture, koje se kao rudiment nalaze u unutrašnjosti tojela (npr. sipina kost). Jedini oblik sa spoljašnjom, spiralnom ljušturom je nautilus, za koga se smatra da je „živi fosil“, jer je star oko 350 miliona godina. Glavonošci su grups mehkušaca koji žive ekušci isključivo u morima. Predstavljaju jednu od najnaprednijih grupa beskičmenjaka.[1][2]

Procjenjuje se da sada ima oko 700 živećih vrsta, iako se njihov broj svake godine povećava, pri čemu će se neke vrste još uvijek otkriti. Pored toga, procenjuje se da je broj izumrlih vrsta oko 11.000. Glavonošci su podeljeni u tri podrazreda:

Podrazred Nautiloidea

Podrazred Ammonoidea †

Podrazred Coleoidea

Glavonošci (lat. Cephalopoda) su mehkušci koje karakterizira bilateralna simetrija i kod kojih se od stopala obrazuju ručice i mišićni lijevak. Većina ima reducirane ili sasvim zakržljale ljušture, koje se kao rudiment nalaze u unutrašnjosti tojela (npr. sipina kost). Jedini oblik sa spoljašnjom, spiralnom ljušturom je nautilus, za koga se smatra da je „živi fosil“, jer je star oko 350 miliona godina. Glavonošci su grups mehkušaca koji žive ekušci isključivo u morima. Predstavljaju jednu od najnaprednijih grupa beskičmenjaka.

Høgguslokkar (frøðiheiti - Cephalopoda) hava altíð hugtikið menniskjur. Fólk hildu teir vera álíkar sjóskrímslum. Høgguslokkar hava onga beinagrind og eru størstir og gløggastir av ryggleysu dýrunum. Sjónin er góð, og heilin stórur, og kanningar vísa, at teir læra av royndum. Høgguslokkar eru sera virknir og eru knappir. Teir eru lindýr, og í ætt við skeljadýr og kúvingar. Tó hava teir onga skel uttan, men summir tíggjuermdir høgguslokkar hava súgskálir á ørmunum og brúka tær, tá ið teir taka fong ella ganga eftir botni. Tíggjuermdir høgguslokkar hava átta armar og tveir langar tøkuarmar, sum kunnu rullast saman og strekkjast út. Teir taka fong ella halda honum við tøkuørmunum og stýra við hinum ørmunum, tá ið teir svimja.

Stórir høgguslokkar eru meira enn 9 metrar langir. Høgguslokkur sprænir sjógv út gjøgnum ein tút og fer við fúkandi ferð aftureftir. Áttaermdi høgguslokkurin liggur um dagin á botni í holum og rivum. Um náttina tekur hann krabbar, skeljadýr og smáfiskar. Kjafturin er harður og líkist nevi. Í kjaftinum er rívitunga. Við hvørt fæst fitt av høgguslokki á summum firðum í Føroyum. Hann er gott agn, og grindahvalur etur hann. Í øðrum londum verður hann brúktur til matna.

D' intevissn (Cephalopoda, van 't Oudgrieks κεφαλή / képhalé, « kop », en πούς / pous, « pôot », letterlik koppôotign) vormn e klasse van de molluuskn. Intevissn wordn azo genoemd omdan z' in stoat zyn van inte te speitn woadeure dan z' under goed kunn camoufleern. Ze zyn ook in stoat van te verandern van kleur en azo kunn z'under perfect anpassn an den oendergroend. Der zyn ook sôortn die gebruukmoakn van bioluminescentie (viezn).

Intevissn leevn allêene moar in zout woater, in al de weireldzêen. De mêeste groein rap en leevn mor êen toet twêe joar.

Ze verplatsn under deur woater in under mantel te pompn en der were krachtig uut te persn langs de sifong. Al d' intevissn zyn vlêeseters. Under eetn bestoat surtout uut vis, krabbn, kriftn en molluuskn die gevangn wordn met de zuugnappn ip under grypoarms. Z èn een harte poapegoaiachtign bek en de mêeste sôortn èn ook nog e rasptoenge (de radula) vo de prôoie in stiksjes te scheurn.

Al d' intevissn plantn under vôort via eiers. D'eitjes wordn bevrucht deur 't sperma van de vintjes. 't Antal eiers dat e wuuvetje kan produceern varieert van 30 tot 500.000.

Volgens World Register of Marine Species (23 december 2013):

D' intevissn (Cephalopoda, van 't Oudgrieks κεφαλή / képhalé, « kop », en πούς / pous, « pôot », letterlik koppôotign) vormn e klasse van de molluuskn. Intevissn wordn azo genoemd omdan z' in stoat zyn van inte te speitn woadeure dan z' under goed kunn camoufleern. Ze zyn ook in stoat van te verandern van kleur en azo kunn z'under perfect anpassn an den oendergroend. Der zyn ook sôortn die gebruukmoakn van bioluminescentie (viezn).

Intevissn leevn allêene moar in zout woater, in al de weireldzêen. De mêeste groein rap en leevn mor êen toet twêe joar.

Ze verplatsn under deur woater in under mantel te pompn en der were krachtig uut te persn langs de sifong. Al d' intevissn zyn vlêeseters. Under eetn bestoat surtout uut vis, krabbn, kriftn en molluuskn die gevangn wordn met de zuugnappn ip under grypoarms. Z èn een harte poapegoaiachtign bek en de mêeste sôortn èn ook nog e rasptoenge (de radula) vo de prôoie in stiksjes te scheurn.

Al d' intevissn plantn under vôort via eiers. D'eitjes wordn bevrucht deur 't sperma van de vintjes. 't Antal eiers dat e wuuvetje kan produceern varieert van 30 tot 500.000.

Kapalapada (Cephalopoda) ya iku anggota filum moluska. Tuladhané kaya ta gurita, nus, lan sotong. Jenengé duwé teges "endas ing sikil"— dijupuk saka ciriné kéwan kang kusus ya kuwi duwé tentakel ning pinggiré endasé, kang gunané kanggo tangan lan sikil. Ilmu kang njlèntrèhaké Kapalapada dijenengi ngèlmu teutologi (theutology, "ngèlmu babagan nus"), lan kagolong ing cabang saka malakologi.

Kapalapada duwé utek kang bisa tuwuh apik lan ana uga jinisé sing moncèr pangelingé, lan bisa sinau.

Wong miguna anggota-anggota Kapalapada kanggo barang pangan lan ing indhustri.

Manawa dititeni, kéwan iki duwé ciri kaya ta duwé tentakel kang dijangkepi karo piranti sing bisa nyedot. Piranti iki ana ning endas kang gunnané kanggo nyekel panganan. Misalé, ning nus lan sotong duwé 8 tentakel céndhek lan 2 tentakel kang dawa. Nautilus duwé nganti kira-kira 60-90 tentakel. Gurita duwé 8 tentakel. Ning endhas ana sapasang mata kang wis bisa digunakaké kanthi fungsi kang wis apik, ya iku duwé lensa mata lan iris, nanging ora duwé kelopak mata, bisa mbedakaké waneka warna lingkungan. Karo mata kang titen bisa rikat ngindari mungsuh saéngga jinis Mollusca iki luwih maju dibandingaké karo liyané. Ana uga tangan sing fungsiné kanggo nyekel wujudé dadi siji mbentuk gulu, corong, sifon (kanggo dalam mlebu metuné banyu). Sifon iki gunané kanggo piranti nyemprot banyu.

Ning sebelahé weteng ana kantung mangsi kang ngandung pigmen melanin. Kabèh anggota saka kéwan iki duwé, kejaba Nautilus. Gunané mangsi iku ya iku kanggo nghindari mungsuh. Nalika mungsuh teka, mangsi iki bakal disemprotaké liwat sifon. Sawisé banyu butek, dhèwèké bakal ngadohi panggonan mau. Kapalapada iki uga duwé mantel, ana ing pérangan geger (dorsal) kang nemplek ning awak, nanging ning pérangan weteng (ventral) mantelé ora nemplok mula awaké ana ronggané.[1]

Sistem panggilesané saka cangkem, gorokan, weteng, usus, lan silit kang ana ing pérangan awak sing ana ning pinggir ngisoré sifon. Pranané migunani angsang, nanging sistem pangédharané ya iku pangédharan getih katutup. Jantung duwé sabilik lan rong serambi?. Sistem ekskresiné kaya ta rong kanthong ginjel. Sistem saraf kéwan iki ya iku kaya ta simpul utek, simpul sikil, lan simpul piranti-piranti njero. Piranti wewadi ning kéwan iki wis dipisahaké.[1]

Nalika mangsa kawinan, lanangan nyaluraké sèl mani marang rong mantel wadonan migunakaké lengen kang ana ing pérangan weteng, nuli prastawa pawinihan. Ovum bakal thukul lan tumuwuh ning sajeroning awak, nuli netes. Sawisé cukup diwasa bakal metu saka jeroning awak lan urip bébas.[1]

|author-link1= (pitulung) Kapalapada (Cephalopoda) ya iku anggota filum moluska. Tuladhané kaya ta gurita, nus, lan sotong. Jenengé duwé teges "endas ing sikil"— dijupuk saka ciriné kéwan kang kusus ya kuwi duwé tentakel ning pinggiré endasé, kang gunané kanggo tangan lan sikil. Ilmu kang njlèntrèhaké Kapalapada dijenengi ngèlmu teutologi (theutology, "ngèlmu babagan nus"), lan kagolong ing cabang saka malakologi.

Kapalapada duwé utek kang bisa tuwuh apik lan ana uga jinisé sing moncèr pangelingé, lan bisa sinau.

Wong miguna anggota-anggota Kapalapada kanggo barang pangan lan ing indhustri.

De Koppfööt oder Koppföte (Cephalopoda, vun ooldgr. κεφαλή kephalē „Kopp“ un ποδ- pod- „Foot“) sünd en Klass mank de Weekdeerter (Mollusca), de in de See leven deit. Dat gifft Aarden mank de Koppföte, de swemmt free in de See rüm, as de Echten Dintenfische, un annere, de kruupt over den Grund hen, as de Kraken. Hüüdtodaags sünd bi 1.000 Aarden bekannt, de noch leven doot, un bi 30.000 Aarden, de al utstorven sünd.[1] To de Koppföte höört de gröttsten Weekdeerter to, de dat hüdigendags gifft. De gröttste Kaventsmann-Pieldintenfisch, de bitherto funnen wurrn is, weer bi 13 m lang. De Hüser vun de Ammoniten, de al utstorven sünd, weern bit hen to twee m groot.

De Naam „Cephalopoda“ is 1797 vun Georges Cuvier inföhrt wurrn un an de Steed treden vun den ollern Naam Polypen, de al vun Aristoteles un den öllern Plinius bruukt wurrn is. Düsse Naam (vun πολύπους polýpous „Veelfoot“) harr Réaumur 1742 for de Neteldeerter bruukt. In de hüdige Zoologie hett sik dat dörsett.

De ollerhaftigen Aarden, as de Nautiloiden un de Ammoniten, de al utstorven sünd, hefft buten dat Lief en „Huus““ oder „Kasten“, wo se in leven doot. Düsse Kasten besteiht ut Aragonit un gifft jem as Butenskelett Schuul un Stevigkeit. De Schillen vun düssen Kasten hett dree Lagen. Hüdigendags hefft, mank de Koppföte, bloß noch de fiev oder sess Aarden ut dat Geslecht Nautilus so en Butenskelett.

Bi de Koppföte mit en „Binnenkasten“ oder Binnenskelett sünd um de harten Deele Weekdeele umto. De Kasten is in’n Loop vun de Evolutschoon sotoseggen „na binnen wannert“. Bi de Echten Dintenfische hett he hüdigendags de Form vun en Schulp annahmen, bi de Pieldintenfische gifft dat bloß noch en so nömmten „Gladius“. Dor hannelt sik dat um en platten Chitinstaff bi, de as Binnenskelett deent. Bi Kraken is vun dat vörmolige Huus meist gor nix mehr nableven.

Koppföte weert as sunnerlich intelligent mank de Warvellosen ankeken.[2][3][4] Bi Experimente is rutfunnen wurrn, datt Kraken Saken to’n Deel just so goot verstahn könnt, as Hunnen. So könnt se abstrakte Saken begriepen (as Tellen vun 1-4 oder allerhand Formen ut’neen holen) oder kumplexe Probleme lösen (u. a. den Dreihversluss vun en Glas upmaken).

Koppföte sünd de eenzigen Weekdeerter mit en afslaten System vun en Kreisloop. Bi Dintenfische warrt dat Blood dör twee Kemenharten an dat unnere Enn vun de Kemen na de Kemen henpumpt. So gifft dat en hogen Blootdruck un dat Blood kann gau fleten. Dat is wichtig vunwegen den man hogen Stoffwessel bi de Koppföte. In de Kemen kummt Suerstoff in dat Blood. Dat suerstoffrieke Blood warrt nu dör en systeemsch Hart na den Rest vun dat Lief henpumpt.

Mank de Koppföte fritt bloß man de Vampirdintenfisch Sweevstoffe vun Planten un Deerter, de al afsturven sünd. All annern Koppföte sünd aktive Rövers un jaagt Deerter. De Büte finnt se mit de Ogen un griept se mit de Tentakels, wo Suugproppens an sitten doot. Bi Pieldintenfische sitt an düsse Suugproppens ok noch lüttje Hakens an. Echte Dintenfische un Nautilus freet sunnerlich lüttje warvellose Deerter, de up’n Grund leven doot. Pieldintenfische fangt Fisch un Granaat un verlahmt de, wenn se jem in’n Nacken bieten doot. Oktopoden jaagt in’e Nacht un fangt sunnerlich Sniggen, Kreefte un Fisch. Se könnt ehre Büte mit en Gift dootmaken, wat de Oppers eerst mol verlahmen deit. Freten warrt de Büte denn mit Keven (u. a. ut Chitin), de as en Papagoyensnavel utsehn doot.[5] Achternah kummt se dorhen, wo se verdaut warrt.

Allerhand Koppföte sünd sexuell bannig aktiv. Tomeist gifft dat Heken siene Spermatophoren mit de Spermien dor in mit en Arm in dat Seken siene Mantelhöhle. Düsse Arm warrt Hectocotylus nömmt. Bi de Argonauten (Argonautidae) is dat anners: Dor lööst sik de Hectocotylus vun dat Heken af un swemmt aktiv na dat Seken ehre Mantelhöhle rin. Dat kummt, wiel dat antrocken warrt dör cheemsche Stoffe, de vun dat Seken utgaht (Chemotaxis). De Seken ehre Eizellen weert befrucht, wenn se ut den Eileider rutkaamt. Aleggt weern könnt se in Druven (Echte Dintenfische, Kraken) oder in Släuche (Pieldintenfische), wo jummers en grote Masse Eier insitt.

Bitherto is noch nich heel klaar, wie sik dat mit de Koppfööt ehren Stammboom verhollt. Enigermaten klaar is man, datt de Dintenfische (Coleoidea), de Ammoniten (Ammonoidea), de Bactriten (Bactritida) un de wecken Aarden vun de Liekhörner (hier de Unnerklass Actinoceratoida), en monophyleetsche Grupp dorstellt, de ok Neekoppfööt (Neocephalopoda) nömmt warrt, wieldes all annern Koppfööt tohopenfaat weert unner den Naam vun Parlboote (Nautiloidea) oder vun Ooldkoppfööt (Palcephalopoda). Düsse tweede Gruppen is avers wohrschienlich paraphyleetsch, vunwegen, datt antonehmen is, datt de Neekoppfööt vun de Ooldkoppfööt afstammt.

De Ammoniten hefft sik in’n Devon utspunnen ut Vorwesers, de liek utsehn hefft, as Bactriten. Ok de Dintenfische weert vun de Bactriten afleit‘. Vundeswegen sünd de Bactriten en para- oder polyphyleetsche Grupp, de uplööst weern möss.

De Koppfööt oder Koppföte (Cephalopoda, vun ooldgr. κεφαλή kephalē „Kopp“ un ποδ- pod- „Foot“) sünd en Klass mank de Weekdeerter (Mollusca), de in de See leven deit. Dat gifft Aarden mank de Koppföte, de swemmt free in de See rüm, as de Echten Dintenfische, un annere, de kruupt over den Grund hen, as de Kraken. Hüüdtodaags sünd bi 1.000 Aarden bekannt, de noch leven doot, un bi 30.000 Aarden, de al utstorven sünd. To de Koppföte höört de gröttsten Weekdeerter to, de dat hüdigendags gifft. De gröttste Kaventsmann-Pieldintenfisch, de bitherto funnen wurrn is, weer bi 13 m lang. De Hüser vun de Ammoniten, de al utstorven sünd, weern bit hen to twee m groot.

De Naam „Cephalopoda“ is 1797 vun Georges Cuvier inföhrt wurrn un an de Steed treden vun den ollern Naam Polypen, de al vun Aristoteles un den öllern Plinius bruukt wurrn is. Düsse Naam (vun πολύπους polýpous „Veelfoot“) harr Réaumur 1742 for de Neteldeerter bruukt. In de hüdige Zoologie hett sik dat dörsett.

Umi mymba ipy iñakãre (ko jueheguasã Cephalopoda) ha'e opa umi syrymbe hete hu'ũite ha ijyvami hetáva, mymbakuéra ndoguerekóiva pujase'o ha oikóva yguasúpe. Ojeikuaa oiko amo 700 mymba ipy iñakãre juehegua,[1] ha umíva ojeikuaavéva ha'e javevyirana (mymba ijyva poapy), kalama ha sépia.

Ko'ã mymba ijyvakuéra (térã ipykuéra) oĩ iñakã ykére, ijyva hetaite: umi javevyirana hína ijyva poapy, ha umi náutilo hína ijyva 90. Mymba ipy iñakãre oreko hetére tykue hũ ikatu omosẽ ombyai ýre, ojapo upéicha ikyhyjérõ ha okañy arã.

Yvypóra oipuruite ko'ã mymba tembi'u apópe, ho'uite, techapyrãme, kalama chyryry umi tetãme yguasu rembe'ýva.

Umi mymba ipy iñakãre (ko jueheguasã Cephalopoda) ha'e opa umi syrymbe hete hu'ũite ha ijyvami hetáva, mymbakuéra ndoguerekóiva pujase'o ha oikóva yguasúpe. Ojeikuaa oiko amo 700 mymba ipy iñakãre juehegua, ha umíva ojeikuaavéva ha'e javevyirana (mymba ijyva poapy), kalama ha sépia.

Ko'ã mymba ijyvakuéra (térã ipykuéra) oĩ iñakã ykére, ijyva hetaite: umi javevyirana hína ijyva poapy, ha umi náutilo hína ijyva 90. Mymba ipy iñakãre oreko hetére tykue hũ ikatu omosẽ ombyai ýre, ojapo upéicha ikyhyjérõ ha okañy arã.

Yvypóra oipuruite ko'ã mymba tembi'u apópe, ho'uite, techapyrãme, kalama chyryry umi tetãme yguasu rembe'ýva.

Un sefalopoda es cualce membro de un clase de moluscas par esta nome, per esemplo, la calamares, polpos, o nautilos. Esta animales tota maral ave un corpo bilada simetre, un testo protendente, e un grupo de brasos o tentaculos alterada de la pede primitiva de moluscas orijinal. La sefalopodas ia deveni dominante en la periodo ordovisian, representada par nautaloides primitiva. La clase aora conteni sola du suclases, distante relatada: Coeoidea (polpos, calamares, e sepidas), en cual la casca molusca ia es asorbada o asenta, e Nautiloidea (nautilos e alonautilos), en cual la casca esterna resta. Sirca 800 spesies vivente ia es identifiada. Du grupos importante ma estinguid es la Amonoidea (simil a nautilos, ma plu relatada a calamares) e la Belemnoidea (simil a calamares, ma plu relatada a sepidas) de la mesozoica.

└─o Sefalopoda ├─o Nautiloidea (Eda Cambrian) │ └─o Nautilide └─o ├─o Amonoidea (estinguida) └─o Coleoidea (Eda Devonian) └─o Neocoleoidea ├─o Octopodiformes │ ├─o Vampiromorfida │ │ └─o Vampiroteutide │ └─o Octopoda │ ├─o Sirina o Sirata │ └─o Insirina o Insirata │ ├─o Bolitenide │ ├─o Amfitretide │ ├─o Vitreledonelide │ ├─? Idioctopodide │ ├─o Octopodide (Polpos) │ │ ├─o Octopodine │ │ ├─o Eledonine │ │ ├─o Graneledonine │ │ ├─o Megaleledonine │ │ └─o Batipolipodine │ └─o Argonautoidea (Argonautes) │ ├─o Aloposide │ └─o │ ├─o Tremoctopodide │ └─o │ ├─o Ositoide │ └─o Argonautide └─o Decapodiformes └─o ├─o Spirulida │ └─o Spirulide └─o Teutida ├─o │ ├─o Miopsina o Lolijinide │ └─o Sepioida (Sepida) │ └─o Sepida │ ├─o Sepina │ │ ├─o Sepide │ │ └─o Sepiadaride │ └─o Sepiolida │ ├─o Idiosepide │ └─o Sepiolide └─o ├─? Batiteutoida └─o Egopsina (Calamares) ├─o Arciteutide ├─o Bracioteutide ├─o Sicloteutide ├─o Cranchide ├─o Gonatide ├─o Ommastrefide ├─o Onicoteutide ├─o Neoteutide ├─o Tisanoteutide ├─o Ualvisteutide ├─o Istioteutoida ├─o Ciroteutoida ├─o Lepidoteutoida └─o Enoploteutoida

Un sefalopoda es cualce membro de un clase de moluscas par esta nome, per esemplo, la calamares, polpos, o nautilos. Esta animales tota maral ave un corpo bilada simetre, un testo protendente, e un grupo de brasos o tentaculos alterada de la pede primitiva de moluscas orijinal. La sefalopodas ia deveni dominante en la periodo ordovisian, representada par nautaloides primitiva. La clase aora conteni sola du suclases, distante relatada: Coeoidea (polpos, calamares, e sepidas), en cual la casca molusca ia es asorbada o asenta, e Nautiloidea (nautilos e alonautilos), en cual la casca esterna resta. Sirca 800 spesies vivente ia es identifiada. Du grupos importante ma estinguid es la Amonoidea (simil a nautilos, ma plu relatada a calamares) e la Belemnoidea (simil a calamares, ma plu relatada a sepidas) de la mesozoica.

Umachaki (Cephalopoda) nisqakunaqa umapi achka hap'ina chakikunayuq, kachi yakupi kawsaq, aycha mikhuq llamp'ukakunam.

Umachaki (Cephalopoda) nisqakunaqa umapi achka hap'ina chakikunayuq, kachi yakupi kawsaq, aycha mikhuq llamp'ukakunam.

Τα κεφαλόποδα (Cephalopoda) είναι ομοταξία θαλάσσιων οργανισμών που ανήκουν στη συνομοταξία των υδρόβιων μαλακίων, αποτελούν το πιο εξελιγμένο είδος τους και ονομάστηκαν έτσι επειδή τα πλοκάμια τους εκφύονται από το κεφάλι τους. Στην ομοταξία τους περιλαμβάνονται, μεταξύ άλλων, τα θράψαλα, τα καλαμάρια, οι μοσκιοί, οι σουπιές και τα χταπόδια, όπως και είδη που φαινομενικά δεν μοιάζουν ιδιαίτερα στα προηγούμενα, ανάμεσα στα οποία και ο ναυτίλος.

Τα κεφαλόποδα σύμφωνα με το Ίδρυμα Σμιθσόνιαν παρουσιάστηκαν πριν από 500 εκατομμύρια χρόνια, στην κάμβριο γεωλογική περίοδο και άρχισαν σχετικά σύντομα να διαφοροποιούνται σημαντικά. Οι χωριστοί εξελικτικοί δρόμοι που ακολούθησαν τα διάφορα κεφαλόποδα έκτοτε αλλά και η απουσία επαρκών απολιθωμάτων για τις ενδιάμεσες μορφές που πιθανόν υπήρξαν σε αυτό το διάστημα, είναι και ο λόγος που σήμερα είναι δύσκολο να αναγνωρίσει κάποιος με μια πρώτη ματιά τις ομοιότητες και την κοινή καταγωγή όλων των εκπροσώπων τους.

Στα κεφαλόποδα κατατάσσονται όσα είδη έχουν σήμερα (ή είχαν στο παρελθόν μέχρις ότου εκλείψουν), τα εξής κοινά χαρακτηριστικά:

Τα κεφαλόποδα, παρότι έχουν χάσει στην πορεία της εξέλιξης πολλούς εκπροσώπους τους, συνεχίζουν να αποτελούν μια μεγάλη ομοταξία που περιλαμβάνει περίπου επτακόσια είδη. Η μεγαλυτερη ποικιλία τους παρατηρείται στον Ισημερινό και μειώνεται προς τους πόλους. Η ομοταξία τους χωρίζεται με τη σειρά της σε διάφορες υποκατηγορίες (υφομοταξίες).

Από τις συνολικά επτά υφομοταξίες, οι πέντε έχουν εξαφανιστεί και αναφέρονται για λόγους ταξινομίας -τις γνωρίζουμε κυρίως από απολιθώματα. Αυτές είναι οι υφομοταξίες των ορθοκερατιδών (orthoceratoidea), των ακτινοκερατιδών (actinoceratoidea),των ενδοκερατιδών (endoceratoidea), τα οποία μάλιστα έφταναν σε μήκος τα 9 μέτρα, των bactritoidea και των αμμωνιτών (ammonoidea).