en

names in breadcrumbs

Little owls have been associated with humanity for centuries. Athene noctua is seen as an omen of death, a sign of wisdom, and even a symbol of creators across time and civilizations. Little owls can be found on coins, medallions, in literature, and other works of art dating as far back as 8000 to 7500 BCE. The little owls were traded to hunt small birds and even used as domesticated pets. Athene noctua was the bird of Athena, the Greek Goddess of Wisdom, and the origin of the genus name Athene. Little owls can still be found in modern art today. Currently there are 12 recognized subspecies of Athene noctua: A. n. noctua, A. n. vidalii, A. n. indigena, A. n. glaux, A. n. saharae, A. n. lilith, A. n. bactriana, A. n. ludlowi, A. n. orientalis, A. n. plumipes, A. n. impasta, and A. n. spilogastra.

Athene noctua is a very vocal bird with a repertoire of between 22 and 40 different calls. These calls are are used to contact or attract mates, defend territories against enemies and other little owls, alarm, and communicate. The vocalizations occur on average 1.87 times per hour and there is an average of 415 total seconds of calling in an hour. The vocal activity varies with time of year and day. There is usually a peak in calling before and during courtship and is lowest in the winter and summer. Also, there is an increase in call duration at dusk, called a dusk chorus phenomenon and a less pronounced increase at dawn with a lull through the night. There are more song vocalizations than calls at night. Also, little owls have been known to vocalize during daylight. The female call is generally shorter and higher pitched than the male call. The male calls are also louder and clearer than the female calls. When a predator is detected, A. noctua quiets and waits until the threat is presumably gone before resuming vocal activity. It has also been demonstrated that little owls learn to recognize the calls of neighboring little owls versus unknown little owls to reduce energy expenditure during territory defense.

Sight and hearing also allow little owls to perceive their environment. Little owls have retinal cells more similar to diurnal birds and have the poorest visual acuity compared to other birds of prey. Athene noctua can see yellow, green, blue, and (to a lesser extent) red. Little owls can also distinguish between different shades of gray, increasing the ability to see at night. Little owls can also hear sound frequencies of 3 to 4 kilocycles per second (kc/s). This ability to hear allows A. noctua to locate rodents extremely accurately. Little owl pairs often preen and scratch each other and sleep in contact with each other. These tactile cues are used to increase pair bonding between mates. Mutual preening has also been seen amongst fledgling siblings.

Communication Channels: tactile ; acoustic

Other Communication Modes: choruses

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Athene noctua is listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List as least concern. However, there is a documented decline seen throughout Europe of not only little owls, but also other owls. It is important to research little owls to gather information about the general decline of owls. The main contributors to population decline are prey and nest availability and human habitat destruction. The development of nest boxes appropriate for little owls has boosted numbers, while current conservation efforts focus on increasing food availability during the breeding season and gathering more information about the causes of decline.

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Athene noctua can be found nesting in and on the faces of buildings. This is considered unattractive and measures have been taken in some places to avoid this (including nets hung over signs). Other than this superficial damage, Athene noctua has no known adverse affects on humans.

Little owls eat many insects and small mammals, controlling populations that are pests to humans. There has been a dramatic decline in some owl populations throughout Europe, including A. noctua. Athene noctua is perfect for studying owl declines in rural habitats because the species is well known to the public, present in significant numbers, easy to research, and quickly reacts to conservation actions. The presence of A. noctua attracts predators that were once desirable to humans. Due to this, little owls used to be traded and carried on staffs to attract and catch their predators. Little owls were also once traded as pets.

Positive Impacts: controls pest population

Little owls feed mainly on insects and small mammals and can keep these populations under control. Also, A. noctua serves as the prey for other species. Although A. noctua interacts with many species, there are no mutualistic relationships documented. Two commensal species of little owls are Trichophagata petzella and Monopis laevigell. There are at least 67 parasite species of little owls. The main types of parasites are from the groups Protozoa, Sporozoa, Metazoa, Nemathelminthes, Arachnida, and Insecta. The blood parasite Leucocytozoon ziemanni and the ectoparasite dipteran Carnus hemapterus have been reported to use little owls as hosts. It could be stated that A. noctua is a commensal species of humans. The little owls use agricultural landscapes and urban and suburban areas as habitats. Also, little owls have been seen following farming equipment that stirs up insects and taking "smoke" baths in the rising smoke of chimneys.

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Little owls hunt in various ways, even mixing the styles of hunting to suit their prey. They can be found perching and watching the ground or the air. To catch prey items on the ground, A. noctua will run and hop along the ground. They can also catch prey on the ground while flying low. Athene noctua can catch prey out of the air while flying as well. Athene noctua carries its prey with either its beak or claws. Males and females hunt and carry prey similarly, but females seem to prefer to carry prey by the neck, whereas males carry prey more often by the head. Little owls are known to catch prey as heavy as themselves. Little owls also create holes to hold surplus food. Hunting occurs mostly at night or dusk, but they have been seen hunting in daytime. Athene noctua is an opportunistic carnivore that is known to feed on a wide variety of prey including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, insects, molluscs, crustaceans, and other invertebrate species. The diet mainly consists of small rodents and large invertebrates (earthworms and insects). In the palearctic region, A. noctua is recorded to prey on 544 different species. The portions of the prey that little owls cannot digest are compacted internally and regurgitated as a pellet.

Animal Foods: birds; mammals; amphibians; reptiles; fish; insects; terrestrial non-insect arthropods; mollusks; terrestrial worms; aquatic crustaceans

Foraging Behavior: stores or caches food

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats terrestrial vertebrates)

Commonly known as little owls, Athene noctua is found within 84 countries of the Palearctic region and the northeastern portion of the Ethiopian region. The range of Athene noctua extends north to the 56th parallel and south to the southern border of the Palearctic region in Asia. The southern extent includes the Middle East to southern Ethiopia and south of western Europe to northern Niger. The eastern limit of the range borders the Sea of Okhotsk and the western limit is found along the Atlantic Ocean.

Biogeographic Regions: palearctic (Native ); ethiopian (Native )

Athene noctua inhabits a range that encompasses a wide variety of landscapes. This species is adapted to mostly dry climates as rain decreases hunting success. Habitable landscapes also vary in altitude as Athene noctua has been observed at elevations ranging from sea-level to 2600 m. Athene noctua is a cavity nesting species and may reside in tree and rock cavities, crevices in cliffs and man-made structures, and even the nests, holes, and burrows of other animals. It prefers habitats with open hunting grounds, many small prey, areas to perch, cavities for nesting, and a stable climate. These habitat preferences of Athene noctua can be met by many landscapes and thus this species is found in a wide variety of habitats, both natural and man-made. It resides in many natural, temperate regions including: open fields, grasslands, open woodlands, steppes, semi-deserts, deserts, cliffs, non-wooded mountains, and ravines, gorges, and gullies. Athene noctua also strongly associates with anthropogenic habitats including agricultural landscapes (farmlands, meadows, pastures, orchards) and urban and suburban habitats (villages and urban buildings).

Range elevation: Sea-level (0) to 2600 m.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; terrestrial

Terrestrial Biomes: desert or dune ; savanna or grassland ; chaparral ; mountains

Other Habitat Features: urban ; suburban ; agricultural

The longest lifespan of A. noctua in the wild is 15 years and 7 months old, however the median lifespan of A. noctua is 4 years. The mortality rate of adult little owls is between 24.2% and 39% per year. The mortality rate of juveniles is much higher, reported to be between 69% and 94%. The lifespan of little owls is limited mostly by prey and nest availability, but predation, parasites, weather, and human influences (habitat destruction, traffic, chemicals, electrocution, etc.) also effect longevity. Information on A. noctua lifespan is not well documented in both the wild and captivity.

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 15.583 (high) years.

Typical lifespan

Status: wild: 4 (low) years.

At hatching Athene noctua has pink skin, cere, and toes and a light white or gray bill and claws. The first down is called neoptile and is short and white. After one week the second down, the mesoptile, begins to grow and young little owls appear a mottled gray color. The mesoptile resembles feathers but is shorter and softer. On the tenth day, the eyes open and the iris is a light yellow color. For three or four weeks the neoptile is still attached to the mesoptile. Overall the young little owls are grayer and show less contrast in their coloring than adults. Even first year adults have differences in feather shape and texture than older adults.

Little owl adults are mostly a dark brown color with cream markings over the entire body. The cream markings include streaks on the forehead and crown, rings around the eyes, a cream chin, spots and streaks on the breast and abdomen, round spots on the back and tail, and a distinct V-shape mark on the back of the head. The males and females share a similar appearance with males tending to have a lighter face. The bill and iris of A. noctua are bright yellow and the eyelids are dark. The cere, a part of the bill, is grayish to black in color. The legs are gray with a possible yellow tint. The toes are a darker gray to brown or black color and the claws are dark brown to black. Some coloring anomalies have been reported including partial albinism, leucistic coloration, or a russet color.

The wing length of A. noctua has a reported maximum of 174 mm and minimum of 158 mm but normally ranges between 151 mm and 178 mm. The wingspan of male little owls is 557.67 mm (plus or minus 11.90 mm) and for females the wingspan was recorded as 565.64 mm (plus or minus 13.15 mm). Females are generally larger than males and on average have a wing length that is 3 to 5 mm longer than males. Also, one year old little owls have a wing length that is, on average, 3 mm shorter than older adults. The subspecies of A. noctua do differ in sizes with the largest little owls from Tibet and Kashmir mountains and the smallest little owls from northeast Africa.

As the common name suggests, little owls are small with an average weight of 164 g. Male little owls are 9 to 10% lighter than females. The minimum recorded weight of an A. noctua is 98 g, the wild maximum is 270 to 280 g, and the maximum recorded in captivity is 300 to 350 g.

Range mass: 98 to 350 g.

Average mass: 164.0 g.

Average wingspan: 557.67 (males) and 565.64 (females) mm.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; homoiothermic; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: female larger

Little owls have many anti-predator adaptations. Athene noctua is known to call in response to predators as an alarm and defense. When other little owls hear the defense call they will hide. When A. noctua sleeps, the white markings are hidden which allows the owl to camouflage. Also, the V-shaped marking on the back of the head mimics eyes to prevent predation from behind. Further, it has been noted that in the presence of barn owls (Tyto alba), little owls will hide or become silent until the threat is perceived to be gone. Although not a normal predator of A. noctua, sometimes intraguild predation occurs between little owls and Tyto alba. The predators of little owls are larger birds including tawny owls, eagle owls, long-eared owls, peregrine falcons, common buzzards, goshawks, sparrowhawks, red kites, tawny eagles, rough-legged buzzards, booted eagles, lanners, marsh harriers, black kites, imperial eagles, and long-legged buzzards. Other predators include pine martens, feral cats, fox, domestic dogs, and corvids. The main predators of the nests are mammals, including stone martens and common genets. The eggs and chicks of little owls are predated upon by stoats, hedgehogs, brown rats, corvids, and magpies.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: cryptic

The courtship period of A. noctua begins with the male defending his territory. He patrols the borders of his territory and calls. The call serves as both a territorial defense to fend off other males and to attract a mate. Once a potential mate makes contact, pair bonding begins. This includes the little owls flying in pairs and sitting in the same tree. The female begins to make a "begging" call to her partner and this prompts the male to feed her prey he has captured. This feeding habit is important because it indicates that there is enough food to reproduce and feed young and also to supply the female with more food so she can gain weight for egg formation and incubation. The vocalization between partners increases as pair bonding strengthens and the couple begins nest visiting and/or copulation. The male selects potential nests within his territory and, around the time of copulation, he shows the female the nest sites until she selects one. Upon successful copulation, the female will remain in the nest and continue to "beg" her mate for food at an increasing rate. After the young have fledged the bond between the pair decreases and aggression increases. Often the partners are willing to separate at this point but not all do. The little owls show a high rate of mate fidelity. The partners will often fly together and hunt near each other. They also share body contact while sleeping and preen and scratch each other. Scratching and copulation outside of the breeding season has been reported and is believed to reduce aggression between mates when not reproducing. Although A. noctua is monogamous, when little owl densities are high and prey is plentiful, sometimes extra-pair copulations occur.

Mating System: monogamous

Athene noctua is iteroparous (produces a clutch every year). The mating season of A. noctua begins in early February and ends as late as May depending on the region. The time of egg-laying also varies with the location but can begin as early as March and end as late as August when taking into account replacement clutches. The clutch size is normally between 1 and 7, averaging 3.3, but as many as 12 has been recorded. If the first clutch is lost for some reason, a pair can lay a replacement clutch, usually of a smaller size. As soon as the eggs are laid, the incubation period begins. The incubation period is from 18 to 35 days, usually reported as 28 days. Overall hatching occurs approximately one month after laying and owlets are dependent upon the parents for two months. The average weight of newly hatched owlets is 10 to 12 g. The female remains with the nestlings for 16 days. The owlets begin to catch their own prey at 28 days and kill prey at 34 days. The offspring become fledglings as early as 28 days and as late as 35 days. The owlets become juveniles and no longer need parental care between August and the beginning of November. The juveniles settle an average of 2700 m away from their first nest. The little owls reach reproductive age at 1 year.

Hatching success of little owls is as low as 49.3%. Fledging success has been reported as low as 46.6%. These losses can be due to infertility, adults losing or abandoning the nest, predation, low prey availability, and other nest complications. The most important trait linked to the production of young is food availability. The success of young is effected by the distance of the nest to the hunting grounds and by weather during the preceding winter, the breeding season, and after hatching. Supplementing nests with food has been shown to greatly increase the production of young. The number of young fledged per breeding pair ranges from 0.6 to 2.8 fledglings per pair.

Breeding interval: Athene noctua breeds once per year

Breeding season: The breeding season of little owls begins at the earliest in February and continues until May at the latest

Range eggs per season: 1 to 12.

Average eggs per season: 3.3.

Range time to hatching: 18 to 35 days.

Average time to hatching: 28 days.

Range fledging age: 28 to 35 days.

Average time to independence: 12 to 16 weeks.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female): 1 years.

Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male): 1 years.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization ; oviparous

Before copulation occurs, little owls must strengthen pair bonding. Part of this pair bonding includes the male defending his territory and providing food to the female. The female must develop fat reserves to help her produce eggs before the nest site is selected. Before the female lays eggs, she remains in the nest and the male brings prey to her. As soon as the eggs have been laid, the female begins incubating the eggs to keep them warm. Pre-hatching parental investment also includes the male bringing the female food as she incubates the eggs. The eggs hatch after about 28 days and the pre-fledging parental care begins. The male still catches prey and brings it back to the nest for the nestlings and female. The female defends, warms, and feeds her young. After 16 days the female also leaves the nest and begins bringing prey back for the nestlings. The offspring become fledglings as early as 28 days and as late as 35 days. Pre-independence parental care includes the parents still feeding and protecting the owlets one month after they reach fledgling age. Parental care ceases at the beginning of September to the beginning of November. In general, there is a two month post-hatching dependency period in which the parents are very active and energetically stressed. As the brood ages, the activity rates of the parents increase. The males are more active than the females during this period and are the main food provider, possibly linked to their lighter weight allowing them to move further and faster. Also the heavier weight of the females may help them care for and defend the nest. Although the roles of the A. noctua parents are different, both provide provisioning and protection throughout the development of the young.

Parental Investment: altricial ; male parental care ; female parental care ; pre-fertilization (Provisioning, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-hatching/birth (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-weaning/fledging (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female); pre-independence (Provisioning: Male, Female, Protecting: Male, Female)

Resident breeder.

The little owl (Athene noctua), also known as the owl of Athena or owl of Minerva, is a bird that inhabits much of the temperate and warmer parts of Europe, the Palearctic east to Korea, and North Africa. It was introduced into Britain at the end of the 19th century and into the South Island of New Zealand in the early 20th century.

This owl is a member of the typical or true owl family Strigidae, which contains most species of owl, the other grouping being the barn owls, Tytonidae. It is a small, cryptically coloured, mainly nocturnal species and is found in a range of habitats including farmland, woodland fringes, steppes and semi-deserts. It feeds on insects, earthworms, other invertebrates and small vertebrates. Males hold territories which they defend against intruders. This owl is a cavity nester and a clutch of about four eggs is laid in spring. The female does the incubation and the male brings food to the nest, first for the female and later for the newly hatched young. As the chicks grow, both parents hunt and bring them food, and the chicks leave the nest at about seven weeks of age.

Being a common species with a wide range and large total population, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed its conservation status as "least concern".

The little owl was formally described in 1769 by the Austrian naturalist Giovanni Antonio Scopoli under the binomial name Strix noctua.[3] The little owl is now placed in the genus Athene that was introduced by the German zoologist Friedrich Boie in 1822.[4][5] The owl was designated as the type species of the genus by George Robert Gray in 1841.[6][7] The genus name, Athene, commemorates the goddess Athena, whose original role as a goddess of the night might explain the link to an owl. The species name noctua has, in effect, the same meaning, being the Latin name of an owl sacred to Minerva, Athena's Roman counterpart.[8]

The little owl is probably most closely related to the spotted owlet (Athene brama). A number of variations occur over the bird's wide range and there is some dispute over their taxonomy. The most distinct is the pale grey-brown Middle Eastern type known as the Syrian little owl (A. n. lilith). A 2009 paper in the ornithological journal Dutch Birding (vol. 31: 35–37, 2009) has advocated splitting the southeastern races as a separate species, Lilith's owl (Athene glaux), with subspecies A. g. glaux, A. g. indigena, and A. g. lilith. DNA evidence and vocal patterns support this proposal.[9]

Other forms include another pale race, the north African A. n. desertae, and three intermediate subspecies, A. n. indigena of southeast Europe and Asia Minor, A. n. glaux in north Africa and southwest Asia, and A. n. bactriana of central Asia. Differences in size of bird and length of toes, reasons put forward for splitting off A. n. spilogastra, seem inconclusive; A. n. plumipes has been claimed to differ genetically from other members of the species and further investigation is required. In general, the different varieties both overlap with the ranges of neighbouring groups and intergrade (hybridise) with them across their boundaries.[9]

Thirteen subspecies are recognised:[5]

The little owl is a small owl with a flat-topped head, a plump, compact body and a short tail. The facial disc is flattened above the eyes giving the bird a frowning expression. The plumage is greyish-brown, spotted, streaked and barred with white. The underparts are pale and streaked with darker colour.[10] It is usually 22 cm (8.7 in) in length with a wingspan of 56 cm (22 in) for both sexes, and weighs about 180 g (6.3 oz).[11]

The adult little owl of the most widespread form, the nominate A. n. noctua, is white-speckled brown above, and brown-streaked white below. It has a large head, long legs, and yellow eyes, and its white "eyebrows" give it a stern expression. Juveniles are duller, and lack the adult's white crown spots. This species has a bounding flight like a woodpecker.[10] Moult begins in July and continues to November, with the male starting before the female.

The call is a querulous kiew, kiew. Less frequently, various whistling or trilling calls are uttered. In the breeding season, other more modulated calls are made, and a pair may call in duet. Various yelping, chattering or barking sounds are made in the vicinity of the nest.[10]

The little owl is widespread across Europe, Asia and North Africa. Its range in Eurasia extends from the Iberian Peninsula and Denmark eastwards to China and southwards to the Himalayas. In Africa it is present from Mauritania to Egypt, the Red Sea and Arabia. It was introduced to the United Kingdom[12] in the 19th century, and has spread across much of England and the whole of Wales. It was introduced to Otago in New Zealand by the local acclimatisation society in 1906, and to Canterbury a little later, and is now widespread in the eastern and northern South Island;[13] it is partially protected under Schedule 2 of New Zealand's Wildlife Act 1953, whereas most introduced birds explicitly have no protection or are game birds.

This is a sedentary species that is found in open countryside in a great range of habitats. These include agricultural land with hedgerows and trees, orchards, woodland verges, parks and gardens, as well as steppes and stony semi-deserts. It is also present in treeless areas such as dunes, and in the vicinity of ruins, quarries and rocky outcrops. It sometimes ventures into villages and suburbs. In the United Kingdom it is chiefly a bird of the lowlands, and usually occurs below 500 m (1,600 ft).[10] In continental Europe and Asia it may be found at much higher elevations; one individual was recorded from 3,600 m (12,000 ft) in Tibet.[14]

This owl usually perches in an elevated position ready to swoop down on any small creature it notices. It feeds on prey such as insects and earthworms, as well as small vertebrates including amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. It may pursue prey on the ground and it caches surplus food in holes or other hiding places.[12] A study of the pellets of indigestible material that the birds regurgitate found mammals formed 20 to 50% of the diet and insects 24 to 49%. Mammals taken included mice, rats, voles, shrews, moles and rabbits. The birds were mostly taken during the breeding season and were often fledglings, and including the chicks of game birds. The insects included Diptera, Dermaptera, Coleoptera, Lepidoptera and Hymenoptera. Some vegetable matter (up to 5%) was included in the diet and may have been ingested incidentally.[10]

The little owl is territorial, the male normally remaining in one territory for life. However, the boundaries may expand and contract, being largest in the courtship season in spring. The home range, in which the bird actually hunts for food, varies with the type of habitat and time of year. Little owls with home-ranges that incorporate a high diversity of habitats are much smaller (< 2 ha) than those which breed in monotonous farmland (with home-ranges over 12 ha). Larger home-ranges result in increased flight activity, longer foraging trips and fewer nest visits.[15] If a male intrudes into the territory of another, the occupier approaches and emits its territorial calls. If the intruder persists, the occupier flies at him aggressively. If this is unsuccessful, the occupier repeats the attack, this time trying to make contact with his claws. In retreat, an owl often drops to the ground and makes a low-level escape.[16] The territory is more actively defended against a strange male as compared to a known male from a neighbouring territory; it has been shown that the little owl can recognise familiar birds by voice.[17]

The little owl is partly diurnal and often perches boldly and prominently during the day.[14] If living in an area with a large amount of human activity, little owls may grow used to humans and will remain on their perch, often in full view, while people are around. The little owl has a life expectancy of about 16 years.[12] However, many birds do not reach maturity; severe winters can take their toll and some birds are killed by road vehicles at night,[12] so the average lifespan may be on the order of 3 years.[11]

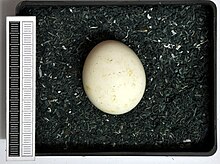

This owl becomes more vocal at night as the breeding season approaches in late spring. The nesting location varies with habitat, nests being found in holes in trees, in cliffs, quarries, walls, old buildings, river banks and rabbit burrows.[14] A clutch of 3 to 5 eggs is laid (occasionally 2 to 8). The eggs are broadly elliptical, white and without gloss; they measure about 35.5 by 29.5 mm (1.40 by 1.16 in). They are incubated by the female who sometimes starts sitting after the first egg is laid. While she is incubating the eggs, the male brings food for her. The eggs hatch after 28 or 29 days.[10] At first the chicks are brooded by the female and the male brings in food which she distributes to them. Later, both parents are involved in hunting and feeding them. The young leave the nest at about 7 weeks, and can fly a week or two later. Usually there is a single brood but when food is abundant, there may be two.[12] The energy reserves that little owl chicks are able to build up when in the nest influences their post-fledgling survival, with birds in good physical condition having a much higher chance of survival than those in poor condition.[18] When the young disperse, they seldom travel more than about 20 km (12 mi).[9] Pairs of birds often remain together all year round and the bond may last until one partner dies.[9]

A. noctua has an extremely large range. It has been estimated that there are between 560 thousand and 1.3 million breeding pairs in Europe, and as Europe equates to 25 to 49% of the global range, the world population may be between 5 million and 15 million birds. The population is believed to be stable, and for these reasons, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed the bird's conservation status as being of "least concern".[1]

Owls have often been depicted from the Upper Palaeolithic onwards, in forms from statuettes and drawings to pottery and wooden posts, but in the main they are generic rather than identifiable to species. The little owl is, however, closely associated with the Greek goddess Athena and the Roman goddess Minerva, and hence represents wisdom and knowledge. A little owl with an olive branch appears on a Greek tetradrachm coin from 500 BC (a copy of which appears on the modern Greek one-euro coin) and in a 5th-century B.C. bronze statue of Athena holding the bird in her hand. The call of a little owl was thought to have heralded the murder of Julius Caesar.[19][20]

In Bulgarian and Romanian folklore, the little owl is said to be a harbinger of death.[21] In 1992, the little owl appeared as a watermark on Jaap Drupsteen’s 100 guilder banknote for the Netherlands.[22]

In 1843 several little owls that had been brought from Italy were released by the English naturalist Charles Waterton on his estate at Walton Hall in Yorkshire but these failed to establish themselves. Later successful introductions were made by Lord Lilford on his Lilford Hall estate near Oundle in Northamptonshire and by Edmund Meade-Waldo at Stonewall Park near Edenbridge, Kent. From these areas the birds spread and had become abundant by 1900.[23] The owls acquired a bad reputation and were believed to prey on game bird chicks. They therefore became a concern to game breeders who tried to eliminate them. In 1935 the British Trust for Ornithology initiated a study into the little owl's diet led by the naturalist Alice Hibbert-Ware. The report showed that the owls feed almost entirely on insects, other invertebrates and small mammals and thus posed little threat to game birds.[24][25]

There is evidence that from the 19th century little owls were occasionally kept as ornamental birds. In Italy, tamed and docked little owls were kept to hunt rodents and insects in the house and garden.[26]

More common was keeping little owls to use them in so-called cottage hunting. This took advantage of the fact that many bird species react to owls with aggressive behaviour when they discover them during the day (mobbing). Such huntings, particularly with tawny owls, were practiced in Italy from 350 B.C. until the 20th century and in Germany from the 17th to the 20th century.[27] In Italy, mainly skylarks were caught in this way. The main place of trade was Crespina, a small town near Pisa. Here, little owls were traditionally sold on 29 September, after being taken from their nests and raised in human care.[27] Only since the 1990s has this trade been officially banned; however, because of the long cultural tradition for hunting with little owls, exemptions are still granted. Thus, there is still a breeding center for little owls near Crespina, which is maintained by hunters.[28][29]

The little owl (Athene noctua), also known as the owl of Athena or owl of Minerva, is a bird that inhabits much of the temperate and warmer parts of Europe, the Palearctic east to Korea, and North Africa. It was introduced into Britain at the end of the 19th century and into the South Island of New Zealand in the early 20th century.

This owl is a member of the typical or true owl family Strigidae, which contains most species of owl, the other grouping being the barn owls, Tytonidae. It is a small, cryptically coloured, mainly nocturnal species and is found in a range of habitats including farmland, woodland fringes, steppes and semi-deserts. It feeds on insects, earthworms, other invertebrates and small vertebrates. Males hold territories which they defend against intruders. This owl is a cavity nester and a clutch of about four eggs is laid in spring. The female does the incubation and the male brings food to the nest, first for the female and later for the newly hatched young. As the chicks grow, both parents hunt and bring them food, and the chicks leave the nest at about seven weeks of age.

Being a common species with a wide range and large total population, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed its conservation status as "least concern".