en

names in breadcrumbs

Actinopterygian fossils first appeared in deposits from the late Silurian (425 to 405 Ma) or early Devonian (405 to 345 Ma) period. While there is a need for more research to understand the evolutionary relationships among the earliest actinopterygians, ichthyologists have found that actinopterygians did not begin to dominate the fish fauna until the beginning of the Carboniferous period, 360 million years ago (Ma). The most derived forms (i.e. teleosts) were uncommon until the late Cretaceous (144 to 65 Mz) period. It was at this time that major diversification began and has continued to this day, as actinopterygians dominate the world’s fish fauna.

The earliest actinopterygians are grouped in the subclass Chondrostei, of which only sturgeons , bichirs and paddlefishes survive today. The rest of the actinopterygians, which includes the vast majority of species, are in the subclass Neopterygii, meaning ‘new fins’. Further, the large majority of neopterygians are placed in the group Teleostei (infraclass). The bowfin is the only surviving species of the halecomorphs, the largest group outside of the teleosts and gars (order Lepisosteiformes – also known as Semionotiformes), with seven species, are the only other surviving non-teleosts.

Ray-finned fishes have significant aesthetic, cultural, scientific and transformative value to humans. To many native people, especially in the United States, fish are symbols of cultural tradition and the subject of works of art. Snorkeling, scuba diving, and sport fishing are increasingly popular around the world and, of course, ray-finned fishes have significant scientific and educational value.

Ray-finned fishes perceive the external environment in five major ways – vision, mechanoreception, chemoreception, electroreception and magnetic reception, and to humans several of these sensory systems are entirely alien. Many types of perception are also used by ray-finned fishes to communicate with individuals of the same (conspecifics) or other species (heterospecifics).

Vision is the most important means of communication and foraging for many ray-finned fishes. The eyes of fish are very similar to terrestrial vertebrates so they are able to recognize a broad range of wavelengths. A species’ ability to perceive various wavelengths corresponds to the depth at which it lives since different wavelengths attenuate (become weaker) with depth. In addition to the normal spectrum perceived by most vertebrates, several shallow-water species are able to see ultraviolet light; others, such as anchovies , cyprinids , salmonids and cichlids , can even detect polarized light! Many fishes also have specially modified eyes adapted for sight in light-poor environments and even outside of water (e.g. mudskippers). For example, several families of deepsea fishes (deepsea hatchetfishes , pearleyes , giganturids , barreleyes) have elongate (long and narrow), upward-pointing, tubular eyes that enhance light gathering and binocular vision, providing better depth perception. Also, several deepwater, midwater and a few shallow species actually have internally generated lights around the eyes to find and attract prey and communicate with other species (see below). Light is usually produced in two ways: by special glandular cells embedded in the skin or by harnessing cultures of symbiotic luminous bacteria in special organs.

One way fishes communicate visually is simply through their static color pattern and body form. For instance, juveniles progress through a range of color and shape patterns as they mature, and sexes are often colored differently ( sexual dimorphism). In addition, some fishes are quite good at identifying other species; the Beau Gregory damselfish is apparently able to distinguish 50 different reef fish species that occur within its territory. A second way fishes communicate visually is through dynamic display, which involves color change and rapid, often highly stereotyped movements of the body, fins, operculae, and mouth. Such displays are often associated with changes in behavioral state, such as aggressive interactions, breeding interactions, pursuit and defense. A third form of visual communication is light production, found among numerous fishes in deepsea habitats. Midwater species, such as lanternfishes , hatchetfishes and dragonfishes have rows of lights along the underside of the body, probably for mating and identification as well as foraging. Even some shallow-water species, such as pineconefishes , cardinalfishes and flashlight fish (family Anomalopidae) of the Red Sea utilize internal light sources to form nighttime feeding shoals or for other behavioral interactions.

Mechanoreception includes equilibrium and balance, hearing, tactile sensation, and a ‘distance-touch-sense’ provided by the lateral line (Wheeler, Alwyne 1985:viii). Detecting sound in water can be difficult because waves pass through objects of similar density. Therefore, ray-finned fishes have otoliths, which have greater density than the rest of the fish, in the inner ear attached to sensory hair cells. Since gas bubbles increase sensitivity to sound, many ray-finned fish (e.g. herrings , elephantfishes and squirrelfishes) have modified gas bladders and swimbladders adjacent to the inner ear. Most ray-finned fishes have keen hearing ability and sound production is common but not universal. In groups that do utilize sound for communication, the most common purpose is territorial defense (e.g. damselfishes and European croakers) or prey defense (e.g. herrings , characins , catfishes , cods , squirrelfishes and porcupinefishes). Sound production is also used in mating (for attraction, arousal, approach or coordination) and communication between shoal mates. Stridulation, which involves rubbing together hard surfaces such as teeth (e.g. filefishes) or fins (e.g. sea catfishes), or the vibration of muscles (e.g. drums), is the most common way sound is produced. Often the latter structures have a muscular connection to the swimbladder to amplify sound. Accordingly, the swimbladder itself is the source of the most complex forms of sound production in many groups (e.g. toadfishes , searobins and flying gurnards). The lateral line is composed of a collection of sensory cells beneath the scales and is able to detect turbulence, vibrations and pressure in the water, acting as a close-quarters radar. This sensation is particularly important in the formation of schools (see Behavior) because consistent positioning is essential for turbulence reduction and smooth hydrodynamic functioning. Consequently, individuals are “so sensitive to the movements of companions that thousands of individuals can wheel and turn like a single organism” (Moyle and Cech 2004:206). Experiments have shown that the lateral line sensation can even compensate for loss of sight in some species, such as trout. The fact that several naturally sightless fish occupy caves (e.g. cavefishes) and other subterranean environments, making extensive use of distance-touch sensation, provides further evidence.

Chemoreception involves both smell (olfaction) and taste (gustation), but, as in terrestrial vertebrates , olfaction is much more sensitive and chemically specific than gustation, and each has a specific location and processing center in the brain. Many fishes use chemical cues to find food. Taste buds are scattered widely around the lips, mouth, pharynx, and even the gill arches; and barbels are used for taste reception in many families (most carps , catfishes and cod). However, the use of nares (like nostrils, located on the top of the head) to detect pheromones is probably the most important type of chemoreception in fishes. Pheromones are chemicals secreted by one fish and detected by conspecifics, and sometimes closely related species, producing a specific behavioral response. Pheromones allow fish to recognize specific habitats (such as natal streams in salmon), members of the same species, members of the opposite sex, individuals in a group or hierarchy, young, predators, etc. Some groups in dominance hierarchies even associate the scents of individuals with their particular ranking. Also, groups of closely related species, such as cyprinids , are able to detect ‘fear scents,’ which are pheromones released when the skin is broken (i.e. a predator has attacked), prompting others to adopt some type of predator avoidance behavior.

Some ray-finned fishes, usually inhabiting turbid environments, have specialized organs for electroreception. Several groups can detect weak electrical currents emitted by organs, such as the heart and respiratory muscles, and locate prey buried in sediment (catfish) or in extremely turbid waters (elephantfishes). Elephantfishes and naked-back knifefishes actually produce a constant, weak electrical field around their bodies that functions like radar, allowing them to navigate through their environment, find food, and communicate with mates. In fact, a diverse range of actinopterygian orders have developed the ability to use electricity for communication: Mormyriformes (elephantfishes and Gymnarchidae), Gymnotiformes (six families) , Siluriformes (electric catfishes), and Perciformes (stargazers). The key to electrical communication is not simply the ability to detect electrical fields, but to produce a mild electrical discharge and modify the amplitude, frequency, and pulse length of the signal. This makes electrical signals individually specific, in addition to being sex and species-specific. Consequently, “electrical discharges can have all the functions that visual and auditory signals have in other fishes, including courtship, agonistic behavior and individual recognition” (Moyle and Cech 2004:206). Finally, a few highly migratory ray-finned fishes can apparently detect earth-strength magnetic fields directly, in much the same way sensation occurs with the lateral line. While the specific mechanisms of magnetic reception are unknown, researchers have found magnetite in the heads of some tunas (e.g. yellowfin tuna) and in the nares of some anadromous salmon (subfamily Salmoninae). Presumably, magnetic perception helps fish locate long distance migration routes for both feeding and reproduction.

Clearly ray-finned fishes display considerable complexity in their ability to perceive their environment and communicate with other individuals, yet until recently it was assumed that fish had negligible cognitive ability. Current research, however, indicates that learning and memory are integral parts of fish development and rely on processes very similar to those of terrestrial vertebrates. Experiments have shown, for instance, that individuals can remember the exact location of holes in fishing net years after exposure, and that fish in schools learn faster by following the lead other individuals. Some researcher believe that the cognitive ability of some fishes is even comparable to that of non-human primates.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical ; electric

Other Communication Modes: photic/bioluminescent ; mimicry ; duets ; choruses ; pheromones ; scent marks ; vibrations

Perception Channels: visual ; infrared/heat ; ultraviolet; polarized light ; tactile ; acoustic ; vibrations ; chemical ; electric ; magnetic

The threat to aquatic habitats has grown steadily over the course of the twentieth century and continues today for a variety of reasons, most of which involve human intervention via overexploitation, introduced species, habitat alterations, pollution, and international trade. However, until recently, researchers did not fathom the scope of the problem among marine species because they assumed that broad distributions, the method of reproduction (pelagic dispersal), and the vastness of the marine environment might create a buffer to threats such as overexploitation and ecological decline. Unfortunately, there are worrying signs, such as collapses in many of the world’s fisheries and drastic declines in many large, mobile species (e.g. tunas). Additionally, researchers are finding that some species live quite long and have low reproduction and growth rates, meaning that removal of larger individuals can have significant impacts on populations. Another trade-related threat is excessive removal of exotic reef species using harsh chemicals, such as cyanide, for the aquarium trade.

Freshwater groups, however, account for the vast majority of actual extinctions in ray-finned fishes. The most significant threats are to families with restricted distribution (i.e. endemic) because localized threats can easily eliminate all individuals of a species. Introduced species, such as Nile perch and mosquitofish (genus Gambusia), combined with pollution and habitat alteration have proven particularly disastrous for groups of endemic ray-finned fishes (i.e. cichlids and many cyprinids). At this point, approximately 90 species of ray-finned fishes are known to be extinct or only survive in aquaria, 279 are critically endangered or endangered, and another 506 are listed as vulnerable or near threatened. Families of particular concern (in descending order) are cyprinids , cichlids , silversides , pupfishes , and especially sturgeons and paddlefishes since every member in the latter two families are threatened.

In general, five major developmental periods are recognized in fish: embryonic, larval, juvenile, adult, and senescent. Fish development is known for its confounding terminology, so there are many gray areas within these major categories, and, as with many other animals, many species tend to defy classification into discrete categories. For instance, species in several teleostean families bear live young (viviparous) – Poeciliidae, Scorpaenidae, and Embiotocidae (to name a few), and the young in some families (Salmonidae) seem to emerge as juveniles after hatching (externally) from the egg.

There are two important developmental characteristics that separate fish from most vertebrates: indeterminate growth (growing throughout life) and a larval stage. The fact that most fish (although there are always exceptions) are always growing means they constantly change in terms of anatomy, ecological requirements, and reproduction (i.e. larger size means larger clutches, more mates, better defense, etc. in most species). Increased age is also associated with better survivability, As physiological tolerances and sensitivity improve, familiarity with the local environment accrues, and behavior continues to develop. The larval stage is usually associated with a period of dispersal from the parental habitat. Also, the disappearance of the yolk sac (the beginning of the larval stage according to most researchers) marks a critical period in which most individuals die from starvation or predation.

Recently, researchers of coral reef fishes (mostly of the order Perciformes) have made significant advances concerning the life history of larvae. Nearly all bony coral reef fishes produce pelagic young (meaning they live in the water column for a period of time before settling on reefs), and the length of the stage is highly variable, from only a week in some damselfishes to greater than 64 weeks in some porcupine fishes . Initially, researchers made relatively simplistic assumptions about the pelagic phase, "portray[ing] larvae as little more than passive tracers of water movement that 'go with the flow,' doing nothing much until they bump into a reef by chance and settle at once" (Lies and McCormick 2002:171). Actually, the larvae of most coral reef fishes are endowed with good swimming abilities, good sensory systems, and sophisticated behavior that is quite flexible. And, while mortality rates are quite high at this stage (as with many other actinopterygian larvae), many larvae are able to detect predators at a considerable distance, and they are often transparent (usually larvae) or cryptically colored (many juveniles).

It is important to note that the young of reef fishes develop quite differently from most temperate fishes that have been studied. While the eggs of most temperate fishes hatch from 3 to 20 days after laying, the eggs of most coral reef species hatch within only a day. Also, at any given size, the larvae of reef fishes are more developed than most temperate, non-perciform fish: they have "more complete fins, develop scales at smaller size, [have] seemingly better sensory apparatus at any size, and are morphologically equipped for effective feeding within a few days of hatching" (173). Finally, the settling habitat for reef fishes (coral reefs) tends to be relatively fragmented and, therefore, much more difficult to locate, unlike the habitat of temperate fishes, which tends to have large expanses suitable for settling. This brief glimpse into the pelagic stage of reef fishes reveals the diversity and complexity of development in actinopterygians.

Development - Life Cycle: neotenic/paedomorphic; metamorphosis ; temperature sex determination; indeterminate growth

Actinopterygians, or ‘ray-finned fishes,’ are the largest and most successful group of fishes and make up half of all living vertebrates. While actinopterygians appeared in the fossil record during the Devonian period, between 400-350 million years ago (Ma), it was not until the Carboniferous period (360 Ma) that they had become dominant in freshwaters and started to invade the seas. At present, approximately 42 orders, 431 families, and nearly 24,000 species are recognized within this class but there are bound to be taxonomic revisions as research progresses. Teleosts comprise approximately 23,000 of the 24,000 species within the actinopterygians, and 96 percent of all living fish species (see Systematic/Taxonomic History). The latter estimates, however, will probably never be accurate because actinopterygian species are becoming extinct faster than they can be discovered in some areas, such as the Amazon and Congo Basins. Unfortunately, habitat destruction, pollution and international trade, among other human impacts, have contributed to the endangerment of many actinopterygians (see Conservation Status).

Clearly, given the enormous diversity of this class, entire books could be (and are) written for each of the categories below, so this account does not attempt an exhaustive summary of the diversity of habitats, body forms, behaviors, reproductive habits, etc. of actinopterygians. Instead, each section introduces important ichthyological concepts and terminology, as well as numerous examples from a diverse range of ray-finned fish families. A section of particular interest is Systematic/Taxonomic History because salient features of the evolutionary history of actinopterygians are discussed. The phylogenetic trends within early actinopterygians provide a basis for understanding why this group has been so successful, as more derived forms (i.e. neopterygians and teleosts), which make up nearly all existing ray-finned fishes, have repeated and extended early trends. Many of the sections, such as Physical Description, Reproduction, Behavior and Ecosystem Roles merely scratch the surface, but there are numerous links to family-level ray-finned fish accounts. (‘Fishes’ is used interchangeably with ‘ray-finned fishes’ and 'actinopterygians' from this point forward).

There was no specific information found on negative impacts to humans. However, many fish are poisonous and venomous, and when disturbed, like many other animals, they can inflict serious wounds and death in some cases. This is also true of predatory fishes that are attracted to shiny objects. Humans willingly eat poisonous species considered delicacy, such as pufferfishes. In some cases, people die from consuming poisonous fish. In the great majority of cases, however, fishes have positive or negligible impacts on humans.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (bites or stings, causes disease in humans , poisonous , venomous )

Fishes are obviously of enormous economic import to humans. Primarily, humans consume fish through fishing and aquaculture, and fish are an essential form of protein for millions of people around the world. The farmed salmon industry alone is valued at over 2 billion dollars a year, but unfortunately, aquaculture operations can have serious ecological consequences. Similarly, ray-finned fishes are quite popular in the aquarium trade, and those with high cash value, such as many tropical fishes, are removed in highly damaging (i.e. using poisons) and exploitive ways (see Conservation and Other Comments). Televised sport fishing events are also popular on rivers, lakes, coastal areas and reefs around the world. The fast-growing scuba industry relies heavily on thriving coral reefs with diverse and abundant communities of ray-finned fishes. Finally, of less direct (and severely underappreciated) economic importance are the ecological roles that fishes fill, like controlling insect populations (e.g. many still-water groups like gouramies) and ensuring healthy-functioning aquatic systems, which helps to ensure clean water and reduces the spread of disease.

Positive Impacts: pet trade ; food ; body parts are source of valuable material; ecotourism ; source of medicine or drug ; research and education; produces fertilizer; controls pest population

Ray-finned fishes are essential components of most ecosystems in which they occur. While many ray-finned fishes prey on each other, they can also have significant impacts on nearly all other animals in their habitats. Zooplanktivorous fishes, for instance, select for specific types and sizes of zooplankton when they feed, thus influencing the type and quantity of zooplankton, and, by extension, phytoplankton present in surface waters (zooplankton consume algae; together they are simply termed plankton). When non-native species invade new habitats (usually through human intervention), the fragility of this balance is dramatically illustrated. For instance, when alewives (family Clupeidae) invaded Lake Michigan, they decimated two larger species of zooplankton and dramatically reduced two midsize species, resulting in the increase of ten smaller species and higher algal content. Later, Pacific salmon (genus Oncorhynchus) were introduced into the lake and dramatically reduced alewife populations and the larger zooplankton species recovered. Because the larger species grazed on algae more efficiently, phytoplankton density decreased dramatically and the lake cleared. This is an example of a trophic cascade, and although the ecosystem achieved relative balance in this example, this is not always the case. For instance, the introduction of Nile perch , a voracious predator, into Lake Victoria (Africa) caused a precipitous decline of many small, planktivorous cichlids. These cichlid species exerted considerable predation pressure on zooplankton, and after they were eliminated the zooplankton community changed drastically, to the point that a new and very large cladoceran species appeared in the lake, Daphnia magna. Unfortunately, this introduction resulted in one of the largest mass extinctions of endemic species in modern times, and the repercussions did not stop with the perch introduction. Many local people consumed the smaller cichlid species and hung them in the sun to dry and preserve them. When Nile perch began to impact local cichlid fisheries, locals started to consume Nile perch, but this fish required firewood for drying and preservation because it is much larger. Consequently, deforestation started to occur around Lake Victoria, leading to increased runoff and siltation during rainy periods, and consequently, decreasing water quality. Decreasing water quality further endangered endemic cichlids, resulting in even more extinctions. The latter example illustrates the complexity of ecological interactions and the fact that ecological interactions are not confined to aquatic organisms. Because ray-finned fishes are often important food source to terrestrial organisms (see below), including humans (see Economic Importance and Conservation), changes in ray-finned fish communities can have significant ecological implications.

A variety of terrestrial vertebrates, such as mammals , amphibians , reptiles , and many marine and freshwater birds depend on ray-finned fishes as a primary source of food. Piscivorous ray-finned fishes compete with many of the organisms above and in some cases are involved in symbiotic relationships with them. A simultaneous competitive and commensal (one benefits and the other is unaffected) relationship is found between bluefish and common terns. These two species interact at a critical period of the terns’ feeding cycle, just after mating when there are chicks to feed. At this time, bluefish migrate to feed on anchovies, concentrating and driving them up in the water column, where terns can catch sight of the anchovies (commensalism). However, bluefish reduce anchovies’ populations considerably, and terns that breed after the bluefish migration are usually unsuccessful (competition). There are numerous other examples of symbiosis, mutualism, commensalism and parasitism between ray-finned fishes and other groups. For example, gobies share burrows with several shrimp-like crustaceans (mutualism) or live among sponges and corals (commensalism). Cardinalfishes and pearlfishes live inside large gastropods and mollusks , respectively (inquilism-sheltering inside living invertebrates). Recently, researchers have begun to appreciate the importance of fish in linking terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. This is especially true of anadromous species, which grow primarily in the sea but return to aquatic areas before they, spreading nutrients from the ocean up and down rivers. During rainy periods in tropical watersheds, ray-finned fish forage in flooded areas, consuming seeds and dispersing them throughout the floodplain.

Several groups of invertebrates (mostly marine), such as cone shells , crabs , anemones , squids and siphonophores (colonies of organisms, e.g. man-o-war), also regularly consume various ray-finned fish. There is even some unlikely predators like dinoflagellates , that can cause large fish kills, known as “red tides”. Some dinoflagellates consume the scales of the dead fish as they sink. Ray-finned fishes also have significant impacts on a variety of plant species. The trophic cascade example (above) illustrated an indirect connection between microscopic plants (phytoplankton) and fish, but fish also excrete soluble nutrients into the water, such as phosphorus. Phosphorus is essential for phytoplankton growth, and fish secretions may provide significant amounts of nutrients in some lakes. A more direct connection is simply the consumption of numerous plant species (see Food Habits). Finally, fish may significantly alter the geological dynamics of their habitats. Many ray-finned fish build nests or burrows (e.g. several minnows , trout and salmon and tilefishes), while others break down substrates, such as dead coral, into sand (e.g. parrotfishes , wrasses , surgeonfishes , triggerfishes and pufferfishes).

Ecosystem Impact: disperses seeds; creates habitat; biodegradation ; keystone species ; parasite

Species Used as Host:

Mutualist Species:

Commensal/Parasitic Species:

Based on feeding habits, researchers broadly classify ray-finned fishes as herbivores, carnivores, omnivores, zooplanktivores and detrivores. There is considerable nuance within each of these categories because many fish are opportunistic feeders – they tend to consume whatever is around, especially when food is scarce. However, primary feeding habits are often associated with body form, mouth type and digestive apparatus, as well as teeth. For instance, gars , pike-characids , pike , needlefish , pike killifish and barracuda represent a diverse range of taxa, yet they all have elongate (long and narrow) bodies, long snouts, and sharp teeth with the fins placed toward the back of the body; this is the design of a fast-start predator, which often lurks motionless in the water column, slightly camouflaged and ready to lunge quickly at unsuspecting prey. These fishes are not made for sustained speed and maneuverability, whereas tunas and billfishes (suborder Scombroidei), with their rounded and highly tapered bodies, are streamlined pelagic chasers capable of very high speeds over long periods. These two fishes are termed ram feeders. Other predators avoid the extra energy expenditure of chasing prey, and instead wait passively, depending largely on good vision, explosive thrust and large mouths capable of forming strong vacuums and effectively inhaling prey (the latter method is termed suction feeding). These sit-in-wait predators are often completely hidden with elaborate camouflage or by burying themselves beneath sediment with only the eyes exposed. Fishes of this type include many scorpionfishes , flatheads , hawkfishes , sea basses , stonefishes , stargazers, flatfishes , frogfishes, and lizardfishes.

Herbivorous fishes posses specialized organs, such as extended guts, pharyngeal mills and gizzards, that allow them to exploit various reef plants and algae. Some of the most successful freshwater families (e.g. minnows , catfishes , cichlids), and most abundant coral reef families (e.g. halfbeaks , parrotfishes , blennies , surgeonfishes , rabbitfishes), include many species of herbivorous fishes. Several groups of herbivorous coral reef species defend territories or form feeding shoals (freshwater cichlids have many of the same behaviors). Some parrotfishes and surgeonfishes utilize shoals to overwhelm the defenses of territorial species, thus gaining access to areas with higher concentrations of plant material.

Zooplanktivores, which feed on small crustaceans like water fleas and copepods floating in the water column (termed zooplankton), abound in oceans throughout the world. Groups such as silversides , herrings and anchovies often congregate in feeding shoals numbering in the millions. Smaller shoals of zooplanktivores, such as rabbitfishes and the juvenile forms of many other reef species, are also found hovering above and around coral reefs. The characteristic features of zooplanktivorous fishes are small size, streamlined and compressed bodies, forked tails, few teeth, and a protrusible mouth that forms a circle when open. When patches of zooplankton are particularly high, many pelagic zooplanktivores keep their mouths agape, and when patches are low they pick animals out individually (the latter are also termed suction feeders).

As discussed in Communication, several groups of ray-finned fishes have quite peculiar methods of capturing prey. Deepsea anglerfishes , among many others in the Stomiiformes and Lophiiformes orders, have developed a luminous bait to attract prey in the deep, dark waters they inhabit. Turbid habitats are home to many fishes that utilize electroreception to find prey, and some predators (e.g. knifefishes and the electric eel) use intense electrical shocks of as much as 350 volts to stun prey before consuming them. Archerfishes exploit a food source that is unavailable to most other fishes: terrestrial insects in overlying vegetation. By shooting jets or bullets of water, and correcting for light refraction, archerfishes knock insects down to the water surface and quickly consume them. Finally, some boxfishes and triggerfishes use an equally novel technique for capturing prey. Both groups expel jets of water from their mouths to uncover buried animals, while triggerfishes use jets and their snouts to flip over and consume otherwise inedible prey, such as spiny sea urchins.

Foraging Behavior: stores or caches food ; filter-feeding

Primary Diet: carnivore (Eats terrestrial vertebrates, Piscivore , Eats eggs, Sanguivore , Eats body fluids, Insectivore , Eats non-insect arthropods, Molluscivore , Scavenger ); herbivore (Frugivore , Granivore ); omnivore ; planktivore ; detritivore

Ray-finned fishes inhabit a variety of extreme environments. These include high altitude lakes and streams, desert springs (e.g. pupfishes), subterranean caves (e.g. cavefishes), ephemeral pools, polar seas, and the depths of the ocean (e.g. deepsea anglerfishes). Across these habitats water temperatures may range from -1.8˚C to nearly 40˚C, pH levels from 4 to 10+, dissolved oxygen levels from zero to saturation, salinities from 0 to 90 parts per million and depths ranging from 0 to 7,000 m (Davenport and Sayer 1993 in Moyle and Cech 2004:1)! Some fish even spend considerable time outside of water: mudskippers prey on the invertebrates of mudflat habitats, while airbreathing catfishes and gouramies live in stagnant, low oxygen ponds (among other habitats) or migrate over land to colonize new areas. Another extreme example of habitat adaptation is found in hillstream loaches , which live in the steep, torrential watercourses of Asiatic hillstreams. Hillstream loaches have flattened bodies and utilize suckers, permanently clinging to rock faces so they are not swept downstream. Lanternfishes , hatchetfishes , dragonfishes , deep-sea codfishes , halosaurs and spiny eels all have lights (flashing or constant), created by luminescent bacteria or special glandular cells, to find prey, communicate with other individuals, or for defense in the blackness of their deepsea habitats (see Communication, Food Habits, and Predation).

Disparate localities may have similar geographic conditions, yet fish species composition varies widely across similar regions. In other words, patterns of fish distribution are not simply related to how well a fish is adapted to a particular type of environment, which is why invasive species can be so devastating (see Conservation). The study of zoogeography attempts to answer questions about how and why fish (and other animal) faunas differ across geographic regions. Zoogeography integrates a variety of disciplines within ichthyology (ecology, physiology, systematics , paleontology, geology and biogeography) to explain patterns of fish distribution. While ichthyologists certainly have incomplete knowledge in many of these areas, advances in plate tectonics and phylogenetic systematics have allowed them to define various zoogeographic (or biogeographic) regions (also subregions) and types.

Fresh water covers only a tiny fraction of the earth’s surface (.0093 percent), yet it is home to approximately 41 percent of all fish species. Most of these are concentrated in the tropics (1,500 different species in the Amazon Basin alone), and Southeast Asia probably has the most diverse assemblage of freshwater species. In marine areas, species concentrations are highest around coral reefs, where butterflyfishes and angelfishes , wrasses , parrotfishes and triggerfishes are common. In the arctic seas five notothenoid families dominate: thornfishes , plunderfishes, Antarctic dragonfishes , and notothens.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Native ); palearctic (Native ); oriental (Introduced , Native ); ethiopian (Introduced , Native ); neotropical (Introduced , Native ); australian (Introduced , Native ); antarctica (Native ); oceanic islands (Introduced , Native ); arctic ocean (Native ); indian ocean (Native ); atlantic ocean (Native ); pacific ocean (Native ); mediterranean sea (Introduced , Native )

Other Geographic Terms: holarctic ; cosmopolitan ; island endemic

Ray-finned fishes inhabit a variety of extreme environments. These include high altitude lakes and streams, desert springs (e.g. pupfishes), subterranean caves (e.g. cavefishes), ephemeral pools, polar seas, and the depths of the ocean (e.g. deepsea anglerfishes). Across these habitats water temperatures may range from -1.8˚C to nearly 40˚C, pH levels from 4 to 10+, dissolved oxygen levels from zero to saturation, salinities from 0 to 90 parts per million and depths ranging from 0 to 7,000 m (Davenport and Sayer 1993 in Moyle and Cech 2004:1)! Some fish even spend considerable time outside of water: mudskippers prey on the invertebrates of mudflat habitats, while airbreathing catfishes and gouramies live in stagnant, low oxygen ponds (among other habitats) or migrate over land to colonize new areas. Another extreme example of habitat adaptation is found in hillstream loaches , which live in the steep, torrential watercourses of Asiatic hillstreams. Hillstream loaches have flattened bodies and utilize suckers, permanently clinging to rock faces so they are not swept downstream. Lanternfishes , hatchetfishes , dragonfishes , deep-sea codfishes , halosaurs and spiny eels all have lights (flashing or constant), created by luminescent bacteria or special glandular cells, to find prey, communicate with other individuals, or for defense in the blackness of their deepsea habitats (see Communication, Food Habits, and Predation).

Researchers have long divided freshwater and saltwater habitats. However, habitat boundaries are often crossed by migratory species, some of which are diadromous – meaning they migrate between fresh water and the sea. Depending on the type of migration, they can be anadromous (migrate up rivers to spawn), with a pattern of freshwater-ocean-freshwater (typical of salmon and lampreys), or catadromous (migrate from freshwater to the sea to spawn), which is characteristic of freshwater eels . In the latter family juveniles, carried to river mouths by ocean currents, migrate upstream and live for up to 10 years before returning to spawning grounds in the ocean and dying shortly after (see Behavior as well).

Fresh water covers only a tiny fraction of the earth’s surface (.0093 percent), yet it is home to approximately 41 percent of all fish species. Most of these are concentrated in the tropics (1,500 different species in the Amazon Basin alone), and Southeast Asia probably has the most diverse assemblage of freshwater species. In marine areas, species concentrations are highest around coral reefs, where butterflyfishes and angelfishes , wrasses , parrotfishes and triggerfishes are common. In the arctic seas five notothenoid families dominate: thornfishes , plunderfishes, Antarctic dragonfishes , and notothens.

Habitat Regions: temperate ; tropical ; polar ; saltwater or marine ; freshwater

Terrestrial Biomes: forest ; rainforest

Aquatic Biomes: pelagic ; benthic ; reef ; lakes and ponds; rivers and streams; temporary pools; coastal ; abyssal ; brackish water

Wetlands: marsh ; swamp ; bog

Other Habitat Features: urban ; suburban ; agricultural ; riparian ; estuarine ; intertidal or littoral

Not surprisingly, the lifespan of ray-finned fishes varies widely. In general, smaller fish have shorter lives and vice versa. For instance, many smaller species live for only a year or less, such as North American minnows in the genus Pimephales, a few galaxiids from Tasmania and New Zealand, Sundaland noodlefishes , a silverside , a stickleback , and a few gobies . However, researchers of coral reef fishes are beginning to find that this correlation does not hold for some families. While many people, especially in the business of fisheries, assumed short lifespans for many fish, researchers are starting to find that many live much longer than previously expected. For example, common species, such as the European perch (aka river perch) and largemouth bass can live 25 and 15 to 24 years respectively. Even more impressive, some sturgeons (which are severely threatened) can live between 80 to 150 years. Several species of rockfish (deepwater rockfish , silvergray rockfish and rougheye rockfish) live from 90 to 140 years! These long lifespans have quickly become a serious issue for some fisheries because populations can be decimated if individuals that naturally accumulate in older age classes are removed (see Conservation).

The truly spectacular array of body forms within this class can only be appreciated by familiarizing oneself with some of the more than 25,000 species of actinopterygians – the largest and most diverse of all vertebrate classes – that exist today. Consider the fact that actinopterygians may fly, walk, or remain immobile (in addition to 'swimming'), exist in virtually all types of habitats except constantly dry land (though some can walk over land), feed on nearly every type of organic matter, utilize several types of sensory systems (including chemoreception, electroreception, magnetic reception and a “distance-touch” sensation – see Communication), and some even produce their own light or electricity. In addition, color diversity in ray-finned fishes is “essentially unlimited, ranging from uniformly dark black or red in many deepsea forms, to silvery in pelagic and water-column fishes, to countershaded in nearshore fishes of most littoral [near-shore] communities, to the strikingly contrasted colors of tropical freshwater and marine fishes” (Helfman et al. 1997:367). Of course, extravagant coloration is not helpful for fish at risk of being eaten, yet bright coloration is environment-specific (see Helfman et al. 1997:367) and bright colors at one depth are cryptic at others due to light attenuation (see Communication). Further, color change is common in brightly colored (as well as many other) fishes and occurs under a variety of circumstances. Pigments are responsible for a many types of color change, but there are also structural colors, resulting from light reflecting off of crystalline molecules housed in special chromatophores (cells located mainly in the outer layer of skin). The silvery sheen displayed by many pelagic fishes is an example of structural color. Numerous actinopterygians are also sexually dimorphic (males and females look different), and body form changes drastically during development, so there is significant diversity within, as well as among, species.

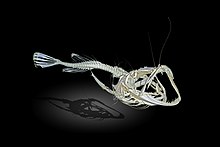

Among the largest actinopterygians are the pirarucu (also known as giant arapaima , up to 2.5m in length) in freshwater and the black marlin (up to 900kg) in saltwater; the longest is the oarfish , Lampris immaculatus, which averages between 5 and 8m in length; and the smallest, a variety of diminutive gobies in saltwater and minnows , catfishes and characins in freshwater. At various points in this account, there is further discussion of physical characteristics as they relate to particular topics (i.e. Systematic/Taxonomic History, Communication, Food Habits and Predation), but for a technical description of actinopterygians, see below. (View an illustration of external fish parts or a fish skeleton).

Actinopterygians may have ganoid, cycloid, or ctenoid scales, or no scales at all in many groups. With the exception of Polypteriformes, the pectoral radials are attached to the scapulo-coracoid, a region of the pectoral girdle skeleton. (The pectoral radials are one of a series of endochondral - growing or developing within cartilage - bones in the pectoral and pelvic girdle on which the fin rays insert). Most have an interopercle and branchiostegal rays and the nostrils are positioned relatively high on the head. Finally, the spiracle (respiratory opening between the eye and the first gill slit – connects with the gill cavity) and gular plate (behind the chin and between the sides of the lower jaw) are usually absent, and internal nostrils are absent.

Other Physical Features: heterothermic ; bilateral symmetry ; polymorphic ; poisonous ; venomous

Sexual Dimorphism: sexes alike; female larger; male larger; sexes colored or patterned differently; female more colorful; male more colorful; sexes shaped differently; ornamentation

Ray-finned fishes generally avoid predators in two ways, through behavioral adaptation and physical structures, such as spines, camouflage and scents. Usually, several behavioral and structural tactics are integrated because it is advantageous for fishes to break the predation cycle (1-4) in as many places as possible, and the earlier the better. For instance, (1) the primary goal of most fish is to avoid detection, or avoid being exposed during certain times of the day. If detected, (2) a fish might try to hide very quickly, blend in with the surroundings, or school; (3) if the fish is about to be attacked then it must try to deflect the attack, and if attack is unavoidable (4) the fish will try to avoid being handled and possibly escape. Therefore, many fishes avoid even the chance of attack through particular cycles of activity, shading (or lighting, see below) and camouflage, mimicking, and warning coloration.

For example, fishes usually avoid dusk because predators often take advantage of quickly changing light conditions that make it difficult for prey to see predators. (Species that feed at dusk are termed crepuscular and include jacks snappers , tarpon , cornetfishes and groupers). Most ray-finned fishes feed during daylight hours (diurnal), when they can see predators. Zooplanktivores, cleaner fishes, and many herbivores are abundant and conspicuous by day but hide within the reef at night. Several wrasses and parrotfishes even secrete a foul-smelling mucous tent or bury themselves in the sediment for protection. Shoaling, which is common among many groups (found in sticklebacks , bluegills , gobies and many others), provides many benefits as a daytime defense. Some predators actually mistake shoals for large fish and avoid attacking. Also, when shoals detect predators they form a tight, polarized group, or school, that is able make synchronous motions. Attacking predators may find it difficult to isolate individuals as the school morphs around them, and some groups (snappers , goatfishes , butterflyfishes , damselfishes , etc.) even mob the predator, nipping and displaying, to thwart an attack.

Because many larger species of zooplankton and other invertebrates come out at night, several groups have developed nighttime feeding patterns (nocturnal) and associated defense mechanisms. Many of these groups, including flashlight fishes , ponyfishes , pineapple fishes and some cardinalfishes , have luminescent organs. While luminescence is likely used for communication (shoaling and mating) and catching prey (via luminescent eyes, which can be turned on and off (!), and baits), several species use luminescence for defense. Rows of lights along the bottom of the body make these fishes indistinguishable to benthic (living at the bottom) predators because they match the intensity of moonlight or dim sunlight shining down. This peculiar method of invisibility is similar to countershading, which is common in several other pelagic ray-finned fishes (as well as sharks and rays). Countershaded fishes are graded in color from dark on top to light on bottom, rendering them invisible from nearly any angle because their coloring is opposite that of downwelling light; the light reflected is equivalent to the background (as above). Two other methods by which pelagic fishes remain invisible are by having a shiny coating (mirror-sided), as in anchovies , minnows , smelts , herrings and silversides ; or by having transparent bodies, like glassfishes , African glass catfishes and Asian glass catfishes.

Benthic ray-finned fishes also utilize numerous methods of camouflage (for both hunting and predator avoidance). A common and elaborate method in tropical seas is mimicking the background of the habitat (protective resemblance), which involves variable color patterns as well as peculiar growths of the skin that may resemble pieces of dead vegetation, corals , and a variety of bottom types (e.g. flatfishes). There are numerous examples of this type of crypticity, from sargassumfishes and leafy seadragons that mimic the seaweed among which they hover, to clingfishes , shrimp fishes and cardinalfishes that have black stripes resembling the sea urchins they use for cover. Another method of camouflage is to look and behave like something inedible, but remain conspicuous. Juvenile sweetlips and batfishes mimic certain types of flatworms and nudibranchs that have toxins in their skin and associated bright coloration, making possible predators wary.

Bold or bright coloration in ray-finned fishes (termed aposematic) usually means that the species posses a structural or chemical defense, such as poisonous spines, or toxic chemicals in the skin and internal organs. Surgeonfishes and lionfishes , for instance, have bold coloration to match scalpel-like and poisonous spines, respectively. Aposematic fishes also advertise their inedibility by moving slowly, instead of darting away when predators are present. However, displays of aggression back up this behavior. When disturbed, weevers erect a dark-colored and highly venomous dorsal spine, while pufferfishes , also poisonous, puff up into a ball of spikes.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: mimic; aposematic ; cryptic

Ray-finned fishes exhibit quite a variety of mating systems. The four major types, along with a few examples, are: monogamy - maintains the same partner for an extended period or spawns repeatedly with one partner (damselfishes , hawkfishes , blennies); polygyny - male has multiple partners over each breeding season (sculpins , sea basses , sunfishes , darters); polyandry - female has multiple partners over each breeding season (anemonefishes); and polygynandry or promiscuity - both males and females have multiple partners during the breeding season (herrings , sticklebacks , wrasses , surgeonfishes). Polygyny is much more common than polyandry, and usually involves territorial males organized into harems (males breed exclusively with a group of females), as in numerous cichlid species and several families of reef fishes (parrotfishes , wrasses and damselfishes , tilefishes , surgeonfishes and triggerfishes).

There are also "alternative mating systems," which include alternative male strategies, hermaphroditism, and unisexuality (Moyle and Cech 2004:161). Alternative male strategies usually occur in species with large males dominating spawning, such as salmon , parrotfishes and wrasses . In this situation, smaller males attempt to 'sneak' fertilize the eggs of females as peak spawning is occurring; the smaller males release gametes simultaneously in the vicinity of the spawning pair. Hermaphroditism in ray-finned fishes involves individuals containing ovarian and testicular tissue (synchronous or simultaneous), as in the black hamlet, as well as individuals that change from one sex to another (sequential). Sequential hermaphrodites most commonly change from being female to male (protogynous), as in parrotfishes , wrasses and groupers . A much smaller number of actinopterygians, such as anemonefishes and some moray eels , change from being male to female (protandrous). Finally, unisexuality (egg development occurring with or without fertilization) can also occur in a variety of forms, and usually involves some male involvement, although at least ones species (Texas silverside) appears to utilize true parthenogenesis – females produce only female offspring with no participation from males. In most cases, however, there is at least some male involvement, either simply to commence fertilization (gynogenesis) or to produce true female hybrids (hybridogenesis).

The mating systems above do not necessarily represent discrete categories and, as with development, the discussion ignores much of the complexity and variety within each system. For instance, one unisexual species, which is actually part of a "species complex" (Mexican mollies), the Amazon molly , uses the sperm from two other bisexual species within the complex (shortfin molly and sailfin molly) to activate development of the eggs; only genetic material from the female lineage is retained (Moyle and Cech, 2004:162; Helfman et. al. 1997:352). This means that the unisexual females are actually parasitizing bisexual males of these other species. Also, many species exhibit a combination of major and alternative mating systems. For instance, hermaphroditism is known among some polygynous wrasses and parrotfishes (among others).

Mating System: monogamous ; polyandrous ; polygynous ; polygynandrous (promiscuous) ; cooperative breeder

Most ray-finned fishes reproduce continually throughout their lifetime (iteroparity), although some (e.g. Pacific salmon and lampreys) spawn only once and die shortly thereafter (semelparity). Fertilization occurs externally in the great majority of species, however in some mouthbrooding species (incubation occurs inside mouth for the purpose of protection, mostly among cichlids), fertilization occurs inside the mouth. In a few families, such as clinids , surfperches , scorpionfishes , liverbearers , eggs are fertilized internally.

During courtship ray-finned fishes exhibit a wide range of complex behaviors, reflecting their evolutionary heritage and the particular environments they inhabit. For instance, pelagic spawners tend to have more elaborate courtship rituals than benthic spawners. Some of the behaviors include sound production, nest building, rapid swimming patterns, the formation of large schools, and many others. In addition, ray-finned fishes frequently change color at specific points in their reproductive cycle, either intensifying or darkening depending on the species, release pheromones, or grow tubercles (tiny bumps of keratin) on the fins, head or body.

One of the more peculiar mating behaviors among actinopterygians is found in deepsea anglerfishes (superfamily Ceratioidea). Many female deepsea anglerfishes are essentially "passively floating food traps"; quite a useful adaptation in the dark, barren waters of the deep sea (Bertelson and Pietsch 1998:140). However, this makes it quite difficult to locate a mate. Finding a female, therefore, is the sole purpose of many males, which are dramatically smaller than females (from 3 to 13 times shorter) and unable to feed as they lack teeth and jaws. With good swimming capabilities and olfactory organs, they are guided to females by pheromones (a unique chemical odor). After finding their mate, males attach themselves to females with hooked denticles, and in some species (Haplophryne mollis) the tissue between the two fuses; the males become permanently attached and receive nourishment from the female while the testes develop.

Key Reproductive Features: semelparous ; iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); simultaneous hermaphrodite; sequential hermaphrodite (Protandrous , Protogynous ); parthenogenic ; sexual ; asexual ; fertilization (External , Internal ); viviparous ; ovoviviparous ; oviparous

While a surprising number of actinopterygian families exhibit parental care, it is not common, occurring only in approximately 22 percent. Unlike mammals , most parental care is the responsibility of males (11 percent), with 7 percent the sole responsibility of females and the rest carried out by both sexes. Not surprisingly, virtually no pelagic spawners, which release their gametes into the water column, exhibit parental care. However, among the fishes that do exhibit parental care, there is considerable diversity.

Some of the most extensive parental behaviors are found in cichlids. Many cichlids brood the eggs in the mouth and, although rare, the free-swimming young of some species also rush into the parent’s mouth for protection. Quite an elaborate form of parental care is found in spraying characin. At peak spawning, males and females of this species make simultaneous leaps out of the water, touching and briefly adhering to the underside of overlying vegetation (a leaf). Each time, a fertilized egg is stuck to the underside of the leaf, usually a dozen or so. Then, to keep the leaf moistened, the male, correcting for the refraction of the water surface, sprays the eggs at one- to two-minute intervals by splashing with his tail. After keeping this up for two to three days (!), the newly hatched young fall into the water. Several tidal species utilize similar methods to keep eggs from desiccating as the tide goes out. Two such methods include coiling the body around the eggs (pricklebacks and gunnels) and covering the eggs with algae (temperate sculpins and wrasses).

Parental Investment: no parental involvement; precocial ; male parental care ; female parental care

Actinopterygii is 'n klas gewerwelde beenvisse van die superklas Osteichthyes met meer as 27 000 spesies. Actinopterygii is afgelei van die Grieks (aktino = straal & pterygion = vin of vlerkie). Die gemeenskaplike faktor van die klas is dat al die visse straalvinvisse is. Dit beteken dat die vinne deur beenstrale ondersteun word. Dit is die strale wat so seer kan steek indien die visse verkeerd hanteer word. Die klas het ook slegs een dorsale vin - wat verdeel mag wees en die neussakke open slegs na buite.

Actinopterygii word in drie infraklasse ingedeel: chondrostei, holostei en teleostei. Laasgenoemde bevat die meeste lewende visse ter wêreld.

Actinopterygii is 'n klas gewerwelde beenvisse van die superklas Osteichthyes met meer as 27 000 spesies. Actinopterygii is afgelei van die Grieks (aktino = straal & pterygion = vin of vlerkie). Die gemeenskaplike faktor van die klas is dat al die visse straalvinvisse is. Dit beteken dat die vinne deur beenstrale ondersteun word. Dit is die strale wat so seer kan steek indien die visse verkeerd hanteer word. Die klas het ook slegs een dorsale vin - wat verdeel mag wees en die neussakke open slegs na buite.

Actinopterygii word in drie infraklasse ingedeel: chondrostei, holostei en teleostei. Laasgenoemde bevat die meeste lewende visse ter wêreld.

Los actinopterigios (Actinopterygii, del griegu ακτινος aktinοs, «rayu» y πτερυγιον pterygion, «aleta») son una clase de pexes óseos (Osteichthyes*). Son el grupu dominante de los vertebraos, con más de 27.000 especies actuales, y desenvolvieron estratexes adaptatives que-yos dexaron colonizar toa clase d'ambientes acuáticos, tantu Agua de mar marinos como d'agua duce y salobres. Les especies más conocíes de pexes pertenecen a esti grupu: truches, salmones, sardines, lucios, perques, sardines, atunes, cíclidos, pexes planos, carpes, anguiles, etc.

La carauterística principal de los actinopterigios ye la posesión d'un cadarma d'escayos ósees nos sos aletes. Ello ye que'l términu Actinopterygii significa "aletes radiaes". Tienen el craniu cartilaxinosu (en parte calcificado) recubiertu por güesos dérmicos, y un solu par d'abertures branquiacubrir por un opérculu. Tamién se caractericen por presentar escames ganoidees (calter autapomórfico, esto ye, esclusivu del grupu) que presenten ganoína, texíu óseo esponxosu y texíu óseo llaminar. Nos pexes actuales la escama ganoidea amenórgase (leptoidea) presentándose dos tipos: cicloideas y ctenoideas, nes cualos namái presentar texíu óseo llaminar, ensin ganoína nin esponxosu.

La taxonomía ye complexa pa un grupu con tantes especies y diversidá. Na mayoría de les clasificaciones taxonómiques reconociéronse tres subdivisiones de la clase Actinopterygii: Chondrostei, Holostei y Teleostei. Anguaño reagrupáronse en dos, pos los holósteos son un grupu parafilético, polo que tiende a ser abandonada polos sistemes taxonómicos modernos basaos na cladística, que namái almite grupos monofiléticos.

Anguaño acéptense dos subclases dientro de los actinopterigios:

Los actinopterigios arrexuntábense xuntu colos sarcopterigios na clase Osteictios, pero tal agrupación ye parafilética y tiende a ser abandonada.

De siguío inclúyese un llistáu de los grupos hasta'l nivel d'ordes, tabulados de la forma qu'aparenta coincidir cola secuencia evolutiva hasta'l nivel de superorde. La llista ta arrexuntada de FishBase[1] con anotaciones nes diverxencies al respective de Fishes of the World[2] y ITIS-Acinopterygii.[3]

Infraclase Holostei

Infraclase Teleostei

Los actinopterigios (Actinopterygii, del griegu ακτινος aktinοs, «rayu» y πτερυγιον pterygion, «aleta») son una clase de pexes óseos (Osteichthyes*). Son el grupu dominante de los vertebraos, con más de 27.000 especies actuales, y desenvolvieron estratexes adaptatives que-yos dexaron colonizar toa clase d'ambientes acuáticos, tantu Agua de mar marinos como d'agua duce y salobres. Les especies más conocíes de pexes pertenecen a esti grupu: truches, salmones, sardines, lucios, perques, sardines, atunes, cíclidos, pexes planos, carpes, anguiles, etc.

Şüaüzgəcli balıqlar (lat. Actinopterygii) — Sümüklü balıqların yarımsinfi. Müasir balıqlarn 20000-dən çox və ya 95% növü bu yarımsinfə daxildir.

Şüaüzgəclilər (Actinopterygi) - əksəriyyəti müasir dəniz və şirinsu hövzələrində yaşayan müxtəlif gövdə quruluşlu balıqlar yarımsinifi. Şüaüzgəclilər uzun sümük şüalı üzgəcləri olur. Şüaüzgəclilər yarımsinfinə daxil olan balıqların əsas qrupları: paleonisklər (Palaeoniscum), qığırdaqlı və sümüklü qanoidlər və irisümüklülərdir. Ən qədim şüaüzgəclilər şirin sularda yaşamış, paleozoyda meydana gəlmiş, mezozoy və kaynozoy dövrlərində bütün su hövzələrində üstünlük təşkil etmişlər. Qazıntı halında çoxlu nümayəndələri məlumdur.

Şüaüzgəcli balıqlar (lat. Actinopterygii) — Sümüklü balıqların yarımsinfi. Müasir balıqlarn 20000-dən çox və ya 95% növü bu yarımsinfə daxildir.

Şüaüzgəclilər (Actinopterygi) - əksəriyyəti müasir dəniz və şirinsu hövzələrində yaşayan müxtəlif gövdə quruluşlu balıqlar yarımsinifi. Şüaüzgəclilər uzun sümük şüalı üzgəcləri olur. Şüaüzgəclilər yarımsinfinə daxil olan balıqların əsas qrupları: paleonisklər (Palaeoniscum), qığırdaqlı və sümüklü qanoidlər və irisümüklülərdir. Ən qədim şüaüzgəclilər şirin sularda yaşamış, paleozoyda meydana gəlmiş, mezozoy və kaynozoy dövrlərində bütün su hövzələrində üstünlük təşkil etmişlər. Qazıntı halında çoxlu nümayəndələri məlumdur.

Els actinopterigis (Actinopterygii) són el clade dominant dels vertebrats, amb més de 27.000 espècies de peixos, distribuïdes per gairebé tots els ambients aquàtics marins, d'aigua dolça i salabrosos. Han desenvolupat estratègies d'adaptació que els han capacitat per colonitzar tota classe d'ambients aquàtics. Les espècies més conegudes de peixos són actinopterigis; per exemple, ho són la truita, el salmó, la carpa, la tonyina, el rap i la piranya.

La característica principal dels actinopterigis és la possessió d'un esquelet d'espines òssies en les seves aletes. De fet, el terme actinopterygii significa "aletes radiades". Tenen el crani cartilaginós i en part calcificat, recobert per fusos dèrmics, i un sol parell d'obertures branquials cobertes per un opercle. També es caracteritzen per presentar escates ganoides, que estan formades per un estrat ossi amb teixit ossi esponjós i teixit ossi laminar, i un estrat de ganoïdina. En els peixos actuals l'escata ganoide es redueix, i és leptoide, i existeixen dos tipus: Cicloidea i Ctenoidea, que presenten teixit ossi laminar, sense ganoïdina ni teixit esponjós.

La taxonomia és complexa per a un grup amb tantes espècies i diversitat. En la majoria de les classificacions taxonòmiques s'han reconegut tres subdivisions de la classe Actinopterygii:

Actualment s'han reagrupat en dues subdivisions, car els holostis eren un grup parafilètic, i aquests grups tendeixen a ser abandonats pels sistemes taxonòmics moderns basats en evidències filogenètiques.

Actualment s'accepten dues subclasses dins dels actinopterigis:

A continuació s'adjunta la classificació dels actinopterigis fins al nivell de subclasses i superordres; per al llistat ampliat amb els ordres vegeu la classificació dels actinopterigis. S'han ordenat de manera que coincideixi amb la seqüència evolutiva fins al nivell de superordre. La llista està recopilada de Froese i Pauly[1] amb anotacions en les divergències respecte a Nelson[2] i els llistat de la ITIS.[3]

Infraclasse Holostei

Infraclasse Teleostei

Els actinopterigis (Actinopterygii) són el clade dominant dels vertebrats, amb més de 27.000 espècies de peixos, distribuïdes per gairebé tots els ambients aquàtics marins, d'aigua dolça i salabrosos. Han desenvolupat estratègies d'adaptació que els han capacitat per colonitzar tota classe d'ambients aquàtics. Les espècies més conegudes de peixos són actinopterigis; per exemple, ho són la truita, el salmó, la carpa, la tonyina, el rap i la piranya.

Paprskoploutví (Actinopterygii) je třída prehistorických i moderních kostnatých ryb, která je velice velkou a velice úspěšnou skupinou. Tvoří více než polovinu žijících obratlovců. Vznik paprskoploutvých ryb je datován až do spodního devonu 400 miliónů let; ke konci devonu a počátkem karbonu byli již paprskoploutví vedoucí skupinou obratlovců.

Moderní systematika obvykle paprskoploutvé dělí na tři nadřády: chrupavčití (Chondrostei), mnohokostnatí (Neopterygii) a kostnatí (Teleostei). Třída má přibližně 42 řádů se 430 čeleděmi a více než 23 000 druhů.[1][2] Evoluční systematikové se však domnívají, že paprskoploutví mají pravděpodobně poněkud složitější evoluční historii, než aby byli rozčleněni na pouhé tři nadřády. Tato skupina ryb tvoří 96 % všech ryb. Vlivem vymírání ryb je však možné, že mnoho z paprskoploutvých vyhyne dříve, než budou pro vědu vůbec popsány. Celé dvě pětiny všech paprskoploutvých tvoří sladkovodní druhy.[zdroj?] Do června 2016 bylo popsáno 32 578 platných druhů paprskoploutvých ryb, které jsou aktuálně řazeny ve více než 500 čeledích a 72 řádech.[3]

Charakteristické pro paprskoploutvé ryby je vyztužení ploutví kostěnými paprsky.

Paprskoploutvé ryby obývají mnoho extrémních stanovišť. Mezi ty mohou být zahrnuta vysoko položená horská jezera a toky, pouštní prameny a teplé pouštní říčky (jako rod Cyprinodon), podzemní jeskyně, efemérní tůňky, polární moře a hlubiny oceánů. Výše uvedená stanoviště se nacházejí v rozsahu teplot prostředí od −1,8 °C až do 40 °C, v rozsahu pH od 4 do 10 a více, ve vodách s širokým rozsahem rozpuštěného kyslíku od 0 po plné nasycení, ve vodách se salinitou od 0 po 90 ppm a ve vodách s hloubkou 0 do 7 000 m.

Některé ryby stráví většinu času zcela mimo vodu: ryby z rodu lezců Periophthalmus chytají svou kořist tvořenou drobnými bezobratlými v přílivové zóně, zatímco jiné ryby žijí ve strnulém stavu. Jiné se adaptovaly svým přísavným ústrojím na extrémně rychle proudící vody horských oblastí Asie. Zajímavé jsou i svítící a světélkující ryby žijící v hlubinách oceánů z čeledí lampovníkovití, světlonošovití, moridovití a halosaurovití.

Největším zástupcem této skupiny byla zřejmě obří jurská ryba druhu Leedsichthys problematicus z vyhynulé čeledi Pachycormidae s délkou kolem 16 metrů a hmotností v řádu desítek tun[4].

Paprskoploutvé ryby představují významný zdroj lidské potravy.

Paprskoploutví (Actinopterygii) je třída prehistorických i moderních kostnatých ryb, která je velice velkou a velice úspěšnou skupinou. Tvoří více než polovinu žijících obratlovců. Vznik paprskoploutvých ryb je datován až do spodního devonu 400 miliónů let; ke konci devonu a počátkem karbonu byli již paprskoploutví vedoucí skupinou obratlovců.

De strålefinnede fisk (Actinopterygii) er en underklasse, der hører under hvirveldyrene og gælder for 96 % af alle nulevende fiskearter. Gruppen dækker vidt forskellige fisk, både i farve, form og adfærd. Ål, laks og søheste er bl.a. med i gruppen. Navnet kommer af at alle fiskene har finner, som stråler ud fra skelettet, i modsætning til de kvastfinnede fisk, hvor musklerne sidder ude i finnerne. Tilsammen udgør de overgruppen benfisk sammen med lungefisk og de blå fisk. Som en gruppe spiller de strålefinnede fisk en stor rolle i økosystemerne i både ferskvand og saltvand, både som rovdyr og som byttedyr.[1]

Actinopterygii placeres normalt under hvirveldyr [2], sammen med forældretaksonen Osteichthyes (benfisk) som en overgruppe. I nogle tilfælde listes Osteichthyes ikke som en overgruppe, men som en gruppe, mens Actinopterygii listes som en undergruppe.

Som gruppe er de strålefinnede fisk også vidt forskellige. Størrelsen varierer f.eks. kraftigt, lige fra den mindre undergruppe Paedocypris til den kæmpe klumpfisk. Fællestrækkene er bl.a. parrede finner, som afstives af en række benstråler. Det indre skelet består næsten udelukkende af benvæv og hvirvelsøjlen er helt forbenet.[3]

De strålefinnede fisk er yderst forskellige i form, farve, levested, adfærd m.m. De kan leve næsten alle steder i havet, og nogle af arterne kan også leve uden for vandet i et vist stykke tid, plus dybder ned til 7.000 m. Actinopterygia kan svømme, kravle, svæve og være immobile.[1]

De tidligst kendte fossiler er Andreolepis hedei, som går 420 mio. år tilbage (sent i Silur). Denne mikrovertebrat er blevet fundet i Rusland, Sverige og Estland.[4] Selv om Actinopterygia også eksisterede i Devon, var de ikke dominerende i ferskvand indtil i Karbon, da de begyndte at invadere havene.[1]

I følge Tree of Live web project: Teleostei og Lars Skipper: alverdens fisk er der følgende gruppering:

De strålefinnede fisk (Actinopterygii) er en underklasse, der hører under hvirveldyrene og gælder for 96 % af alle nulevende fiskearter. Gruppen dækker vidt forskellige fisk, både i farve, form og adfærd. Ål, laks og søheste er bl.a. med i gruppen. Navnet kommer af at alle fiskene har finner, som stråler ud fra skelettet, i modsætning til de kvastfinnede fisk, hvor musklerne sidder ude i finnerne. Tilsammen udgør de overgruppen benfisk sammen med lungefisk og de blå fisk. Som en gruppe spiller de strålefinnede fisk en stor rolle i økosystemerne i både ferskvand og saltvand, både som rovdyr og som byttedyr.

Die Strahlenflosser (Actinopterygii) sind eine Klasse der Knochenfische (Osteichthyes).

Bis auf die Fleischflosser (Sarcopterygii) gehören alle Knochenfische zu diesem Taxon, das sind insgesamt annähernd die Hälfte aller Wirbeltierarten.[1]

Die Strahlenflosser sind heute weltweit verbreitet und besiedeln alle aquatischen Habitate von der Tiefsee (bis etwa −8.400 Meter)[2] bis ins Hochgebirge (bis etwa 4.500 Meter) und von Thermalquellen (+43 °C) bis zu den Polarmeeren (−1,8 °C). Sie sind in morphologischer, ökologischer und verhaltensbiologischer Hinsicht sehr variabel.[1]

Der wissenschaftliche Name „Actinopterygii“ ist zusammengesetzt aus den altgriechischen Wörtern ἀκτίς (aktís, ‚Strahl‘) und πτερύγιον (pterýgion, ‚Flügel‘ bzw. ‚Flosse‘), entspricht also dem deutschen Trivialnamen „Strahlenflosser“. Er bezieht sich auf die typische Anatomie der Flossen (siehe unten).

Eines der charakteristischsten Merkmale der Strahlenflosser und namensgebend für das Taxon ist die Ausbildung der paarigen Flossen (Brust- und Bauchflossen) in Form sogenannter Strahlenflossen (Actinopterygia, Sg. Actinopterygium). Die Schwestergruppe der Strahlenflosser, die Fleischflosser (Sarcopterygii), besitzen hingegen sogenannte Fleischflossen (Sarcopterygia, Sg. Sarcopterygium). Der überwiegende Teil dieser Strahlenflossen besteht aus den knöchernen Flossenstrahlen (Radii, Sg. Radius) und der Schwimmhaut (Patagium), die von den Radien aufgespannt wird. Die relativ langen Radien sitzen auf einem vergleichsweise kurzen Flossenbasisskelett, wobei proximale (rumpfnahe) Basalia von distalen (rumpffernen), stabförmigen Radialia unterschieden werden. Bei fast allen heute lebenden Strahlenflosser-Taxa fehlen jedoch die Basalia. Die Muskeln für die Flossenbewegung sitzen bei allen Knochenfischen nur am Flossenbasisskelett an. Entsprechend ist die gesamte Flossenbasis, d. h. Flossenbasisskelett nebst Muskeln, bei Strahlenflossern eher unscheinbar. Bei den Fleischflossern ist die Flossenbasis, teilweise auch der unpaaren Flossen, im Vergleich zu den Flossenstrahlen wesentlich länger und kräftiger ausgebildet,[3] sodass ein relativ großer Teil der Flosse beim lebenden Tier „fleischig“ ist.

Die Zahnkronen der Actinopterygier zeichnen sich neben dem Überzug aus normalem Zahnschmelz (Ganoin) durch eine zusätzliche kleine Kappe oder „Warze“ aus Acrodin, einer sehr harten, transparenten, schmelzartigen Substanz, an der Spitze der Krone (Apex) aus.

Die vordere der beiden Rückenflossen im Grundbauplan der Knochenfische fehlt: Diese primär einzelne Rückenflosse der Strahlenflosser kann aber sekundär in mehrere Flossen geteilt sein.

Die Schuppen sind durch ein Hakensystem gelenkig miteinander verbunden. Sie sind ursprünglich stark mineralisiert, d. h. mit einer Schicht aus Ganoin überzogen (Ganoidschuppe).[1] Dieser Zustand ist bei fossilen Strahlenflossern des Paläozoikums und Mesozoikums weit verbreitet, findet sich heute aber nur noch bei Stören (Acipenseridae) und Knochenhechten (Lepisosteidae). Der mit Abstand häufigste Schuppentyp bei den heute lebenden Strahlenflossern ist jedoch die Elasmoidschuppe. Bei dieser ist das Ganoin bis auf mikroskopische Reste reduziert.

Entgegen der Ansicht von den „stummen Fischen“ ist die Erzeugung von Tönen und die zwischenartliche Kommunikation mittels Lauten unter den Strahlenflosser weit verbreitet. Dies wurde bisher bei 172 der 470 Familien der Strahlenflosser nachgewiesen.[4]

Die Lophosteiformes und Naxilepis, bruchstückhafte Funde aus dem späten Silur (etwa 420 mya) von Europa und Sibirien bzw. China, galten einst als die ältesten fossilen Überreste von Strahlenflossern. Mittlerweile stuft man diese Vertreter jedoch als basale Knochenfische ein.[5][6] Meemannia, ursprünglich als primitiver Fleischflosser eingeordnet, zeigt einen strahlenflosserartigen Schädel und ist etwa 415 Millionen Jahre alt (Unterdevon).[7] Die ältesten Skelettfunde, die man sicher Strahlenflossern zuordnen kann, stammen aus dem Mitteldevon (etwa 380 mya) von Europa und Kanada (Cheirolepis). Weitere europäische Skelettfunde aus dieser Zeit sind Stegotrachelus, Moythomasia und Orvikuina.[1]

Zu den Strahelnflossern (Actinopterygii) gehören die folgenden natürlichen Gruppen:

Mit über 30.000 Arten sind die Teleostei die mit Abstand artenreichste Fischgruppe (96 %).[8] Ihre Diversität macht etwa 50 % der der Artenvielfalt aller heute lebenden Wirbeltiere aus. Insgesamt 15.150 Arten sind Süßwasserfische, 14.740 Arten kommen im Meer vor und 720 Arten sind in beiden Biotopen und im Brackwasser beheimatet.[9]

Das nachfolgende Kladogramm gibt eine Übersicht über die verwandtschaftlichen Beziehungen der verschiedenen Kladen von rezenten Strahlenflossern untereinander, sowie zwischen den Strahlenflossern und anderen rezenten Gruppen von Fischen und den Tetrapoden (Vierfüßer):

Wirbeltiere KiefermäulerSauropsiden (Reptilien, Vögel) ![]()

Amphibien (Lurche) ![]()

Polypteriformes (Flösselhechte, Flösselaal) ![]()

Acipenseriformes (Störe, Löffelstöre) ![]()

Lepisosteiformes (Knochenhechte) ![]()

Teleostei (Echte Knochenfische) ![]()

Knorpelfische (Haie, Rochen, Seekatzen) ![]()

Kieferlose Fische (Schleimaale, Neunaugen) ![]()

Im Folgenden wird die Systematik nach dem Standardwerk Fishes of the World dargestellt († = ausgestorben):[10]

Strahlenflosser (Actinopterygii)

Die Strahlenflosser (Actinopterygii) sind eine Klasse der Knochenfische (Osteichthyes).

Bis auf die Fleischflosser (Sarcopterygii) gehören alle Knochenfische zu diesem Taxon, das sind insgesamt annähernd die Hälfte aller Wirbeltierarten.

Die Strahlenflosser sind heute weltweit verbreitet und besiedeln alle aquatischen Habitate von der Tiefsee (bis etwa −8.400 Meter) bis ins Hochgebirge (bis etwa 4.500 Meter) und von Thermalquellen (+43 °C) bis zu den Polarmeeren (−1,8 °C). Sie sind in morphologischer, ökologischer und verhaltensbiologischer Hinsicht sehr variabel.

Actinopterygii è na classi di pisci e rapprisèntanu lu gruppu cchiù granni dî virtibrati, cumprinnennu cchiù di 27.000 speci di pisici chi s'attròvanu ntra l'acqui duci e marini. La sò carattirìstica principali, suggiruta dû sò nomu, è di pussèdiri pinni sustinuti di raji.

The Actinopterygii /ˌæktᵻnˌɒptəˈrɪdʒi.aɪ/, or ray-finned fishes, constitute a class or subclass o the bony fishes.

The ray-finned fishes are so cried acause thay possess lepidotrichia or "fin rays", thair fins being webs o skin supportit bi bony or horny spines ("rays"), as opponed tae the fleshy, lobed fins that characterize the class Sarcopterygii which an aa, however, possess lepidotrichia. These actinopterygian fin rays attach directly tae the proximal or basal skeletal elements, the radials, which represent the link or connection atween these fins an the internal skelet (e.g., pelvic an pectoral girdles).

In terms o nummers, actinopterygians are the dominant class o vertebrates, comprisin nearly 99% o the ower 30,000 species o fish (Davis, Brian 2010). Thay are ubiquitous throughoot freshwatter an marine environments frae the deep sea tae the heichest muntain streams. Extant species can range in size frae Paedocypris, at 8 mm (0.3 in), tae the massive ocean sunfish, at 2,300 kg (5,070 lb), an the lang-bodied oarfish, at 11 m (36 ft).

Actinopterygii es un superclasse de Osteichthyes.

Los actinopterigians son los peisses de nadarèlas raionadas. Son lo grop dominant amb 27 000 espècias pertot dins las aigas doças e los environaments marins. Son tradicionalament tractats coma una sosclassa dels osteictians, o peis ossós, mas coma lo grop es parafiletic pòdon èstre tractats coma una classa biologica completa.

Ang Actinopterygii ( maglaro / ˌ æ k t ɨ sa n ɒ p t ə r ɪ dʒ i. aɪ / ), o ray-may palikpik na isda, may isang klase o sub-class ng payat na payat isda.

Ang mga ray-may palikpik isda ay kaya tinatawag na dahil sila ay nagtataglay lepidotrichia o "palikpik ray", ang kanilang mga palikpik pagiging webs ng balat na suportado ng matinik o masungay spines ("ray"), bilang laban sa mataba, lobed palikpik na magpakilala sa klase Sarcopterygii na rin, gayunpaman, nagtataglay lepidotrichia. Maglakip ng direkta ang mga actinopterygian palikpik ray sa proximal o saligan ng kalansay elemento, ang mga radials, na kumakatawan sa link o koneksiyon sa pagitan ng mga palikpik at ang panloob na balangkas (halimbawa, pelvic at pektoral girdles).

Sa mga tuntunin ng mga numero, mga actinopterygians ang nangingibabaw na klase ng mga vertebrates, na binubuo ng halos 96% ng 25,000 species ng mga isda (Davis, Brian 2010). Sila ay nasa lahat ng pook sa buong sariwang tubig at kapaligiran ng marine mula sa deep sea sa pinakamataas na bundok stream. Maaaring saklaw ng mga nabubuhay pa na species sa laki mula sa Paedocypris, sa 8 millimeters (0.31 in), ang napakalaking Ocean Sunfish, sa 2300 kilo (£ 5100), at ang pang-bodied Oarfish, sa hindi bababa sa 11 metro (36 piye).

The Actinopterygii /ˌæktᵻnˌɒptəˈrɪdʒi.aɪ/, or ray-finned fishes, constitute a class or subclass o the bony fishes.

The ray-finned fishes are so cried acause thay possess lepidotrichia or "fin rays", thair fins being webs o skin supportit bi bony or horny spines ("rays"), as opponed tae the fleshy, lobed fins that characterize the class Sarcopterygii which an aa, however, possess lepidotrichia. These actinopterygian fin rays attach directly tae the proximal or basal skeletal elements, the radials, which represent the link or connection atween these fins an the internal skelet (e.g., pelvic an pectoral girdles).